Earlier Puberty as a Predictor of Later Onset of Schizophrenia in Women

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The aim of this study was to determine whether puberty plays a mediating role in onset of schizophrenia. The hypothesis was that there is an inverse relation between age at puberty (menarche) and age at onset in women. METHOD: Competent and consenting individuals with DSM-IV-defined schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and their mothers underwent a 45-minute interview to ascertain age at first odd behavior, age at first psychotic symptoms, age at first hospitalization, and ages at various indices of puberty. Information about substance use, head injury, perinatal trauma, and first-degree family history of schizophrenia was also obtained. RESULTS: In the women (N=35), the earlier the age at menarche, the later the ages at both the first psychotic symptoms and the first hospitalization. There was no significant association between puberty and onset in the men (N=45). Other than gender, none of the examined variables played a role in the interaction of puberty and onset of illness. CONCLUSIONS: In women, early puberty (whether through hormonal or social influence) was associated with later onset of schizophrenia. This effect was not found in men; in fact, the trend was in the opposite direction.

The purpose of this investigation was to explore the relation between age at puberty and age at onset of schizophrenia in women and men. Given the reported gender difference in mean age at onset of schizophrenia (1–4) and the many known CNS effects of estrogens (5–14), we hypothesized that the hormonal milieu resulting from early puberty would delay onset of psychosis in women.

We were uncertain whether this association would also be present in men. There is ample evidence that the action of testosterone in the brain is mediated to some extent through estrogens. Although the androgen-to-estrogen conversion rate is small (0.1%–1.0%), the relatively very high pubertal androgen levels in men may result in brain estrogen concentrations as high as those in women (15) However, since no association between puberty and onset of schizophrenia had previously been reported, and since most studies use male subjects, we hypothesized that the effect would either be absent or work in the opposite direction in men.

We also felt that it was important to determine whether other variables influence the relation between age at puberty and age at onset of illness. These variables included substance use (16), head injury (17), obstetric complications (18), and family history of schizophrenia (19). The presence of all of these variables has been reported to bring forward the age at illness onset. Therefore, it was important to determine their temporal relation to age at onset of illness in this population.

METHOD

Power analyses (20) conducted at the outset of the study indicated that 35 male and 35 female participants were required to adequately test the study hypotheses. Recruitment continued until we had a group of 35 female and 45 male subjects, who provided written informed consent after a complete description of the study. Recruitment efforts were limited to individuals in treatment for DSM-IV-defined schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder diagnosed within the preceding 10 years. Most participants were drawn from the Centre for Addictions and Mental Health, Clarke Division, Toronto. Additional recruitment sites were Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center, Toronto; Whitby Mental Health Center, Whitby, Ont.; and Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia.

In addition to the individuals with schizophrenia, we sought the participation of their mothers. Twenty-four (68.6%) of the mothers of the female participants and 33 (73.3%) of the mothers of the male participants were available for interview. Most of the nonparticipation by mothers was a result of the patients’ refusal to give their consent. The other reasons were geographic distance or illness.

Instruments

Diagnosis. As a check on the reliability of multiple diagnosticians, one experienced diagnostician (M.V.S.) completed DTREE diagnoses (21) for 23 of the 35 women and 28 of the 45 men. DTREE is a computerized system for DSM-IV diagnoses. The investigator enters individuals’ symptoms derived from the psychiatric record and is led through a series of questions. Agreement between clinical case conference diagnosis and DTREE diagnosis of schizophrenia is high (kappa=0.80). Procedural validity is similarly high (sensitivity=1.00, specificity=0.80) (22). In the present study, the diagnostic specificity (schizophrenia versus schizoaffective disorder) for the comparison of the DTREE diagnosis and the clinical diagnosis was 82.6% (kappa=0.66) for female subjects and 85.7% (kappa=0.65) for male subjects. High agreement and a limited range of response alternatives accounted for attenuated kappa values.

Schizophrenia onset. The Interview for the Retrospective Assessment of the Onset of Schizophrenia (23) is a semistructured interview for the retrospective assessment of early signs and symptoms of schizophrenia. It is based on the Present State Examination and the ICD and has been adapted for DSM-IV. It pinpoints the presence and temporal order of the first appearance of various signs and symptoms as well as contacts with mental health professionals. From this interview three data points were established: 1) age at first sign of odd behavior, 2) age at first psychotic symptoms, and 3) age at first hospital admission. Interrater reliability is reported as 77%–97% for this interview tool (23, 24). The fact that all participants were within 10 years of first diagnosis allowed for relatively sharp recall by both the participant and the family member. The Interview for the Retrospective Assessment of the Onset of Schizophrenia was administered to both the participant and the relative to yield a consensus age at onset. It had been decided beforehand that in case of discrepant reports, the mother’s report would be relied on for the first sign of odd behavior, the subject’s for first psychotic symptoms, and the psychiatric record for the date of the first psychiatric hospitalization.

Puberty onset. The Maturational Timing Questionnaire (25) is an easily administered seven-item scale with good reported reliability (r=0.73–0.97). In this investigation, the questionnaire was first pilot tested for concordance with five men with schizophrenia and their mothers. Among several male pubertal milestones, the highest concordance rate between participant and mother (80%) was for the age at voice change. Because the literature provides substantial evidence that women’s recall of their age at menarche is accurate (26, 27), pilot testing with women was not considered necessary.

Substance use. The Interview for the Retrospective Assessment of the Onset of Schizophrenia (for substance use) is a semistructured interview developed to assess retrospectively the age at onset, frequency, and persistence of both alcohol and illicit drug use. Investigators report high specificity (kappa=0.65) and sensitivity (kappa=0.52) for recall of alcohol and drug use (28). Only alcohol/drug use before the onset of any psychotic symptom was included. The severity of use was measured on a 7-point scale: 0=no use before onset of psychotic symptoms, 1=experimental use, 2=monthly use, 3=bimonthly use, 4=more than bimonthly use, 5=weekly use, 6=biweekly use, and 7=daily use. It had been decided beforehand that if discrepancies existed between informants, the subject’s report would be used.

Family history. The Family History Questionnaire, based on the Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria (29) for psychiatric disorder in first-degree relatives, was administered to both participants and mothers. Reliability for psychotic illness among different informants has been reported at r=0.79 (30). The presence of a family history was scored as an ordinal variable: 0=no family history, 1=family history suspected, 2=family history definitely present.

Head injury. The Head Injury Questionnaire is a short instrument that was administered to both subjects and mothers to determine if and when the participant had suffered a head injury severe enough to lead to a loss of consciousness. Head injury was scored as present or absent.

Obstetric complications. The Obstetric Complication Scale (31) consists of 17 items covering the prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal period. It was administered to participants and mothers, yielding scores on an ordinal scale: 0=no complications, 1=one or more equivocal but not definite complications, and 2=one or more definite complications. It had been decided beforehand to rely on the mother whenever reports were discrepant. In a schizophrenic population, this scale has previously shown that 33% of individuals (35% of men and 31% of women) fall into a group with definite complications and that 50% fall into a group with no complications.

Procedure

Eligible participants were invited, in person or by telephone, to participate in the study. Each interview appointment began with an explanation of the study followed by a request for written consent to participate, to contact the general practitioner for collaborative information, and to contact the mother to participate in the study. The interview, during which all questionnaires were administered, took approximately 45 minutes to complete. Following the interview, collaborative information was collected from interviews with participating mothers, the psychiatric record, and the general practitioners. On the basis of the information obtained, a single data point was established for each variable and entered into the data analyses.

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses proceeded in three phases. First, descriptive statistics were calculated and compared between female and male participants. Gender differences were assessed by means of independent-groups t tests for continuous measures and chi-square tests for categorical measures. Second, associations between the primary independent and dependent measures, age at onset of puberty, and age at onset of schizophrenia were assessed by means of zero-order correlations. Correlations to index the associations between the primary independent and dependent measures and the additional variables were calculated as well. Finally, hierarchical regression analyses were conducted to assess the possible confounding influences of the additional variables on the relationship between puberty and schizophrenia onset.

RESULTS

As shown in Table 1, for each operational definition of schizophrenia onset, the male subjects’ age at onset was lower than the female subjects’. The difference was statistically significant for age at first psychotic symptoms and for age at first hospital admission. The mean age at onset of puberty for female subjects (i.e., age at first menstruation) was significantly younger than that for male subjects (i.e., age at voice change).

Table 1 shows that for both alcohol and drug use, male participants had significantly higher severity scores than female participants. There were no other statistically significant gender differences in the distributions of any of the remaining variables. Regarding family history of psychotic illness, schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder was present or suspected in a first-degree relative of 17.1% of the female participants and 11.6% of the male participants. For both sexes, psychotic illness was most commonly reported in mothers but was also evenly distributed among siblings and fathers. There was no gender difference in the proportion of participants (about 9%) who had experienced head injury before onset of the first psychotic symptoms (Table 1). More than one-half of the participants had a history of suspected or definite birth complications. Complications usually occurred in the perinatal period and included factors such as the umbilical cord wrapped around the neck, forceps delivery, cesarean section, or abnormal positioning.

Table 2 shows the zero-order correlations among the schizophrenia and puberty onset measures. It also displays the correlations between these primary dependent and independent measures and each of the additional measures.

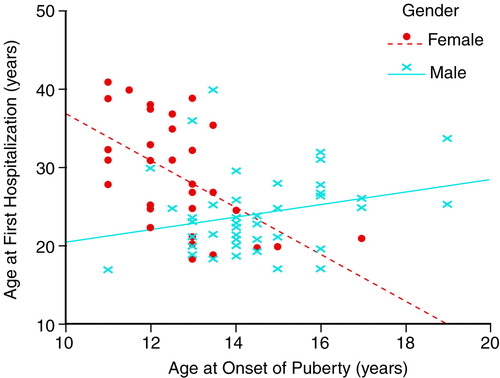

Age at onset of schizophrenia was negatively associated with age at puberty for the female subjects. The correlations were statistically significant for age at first psychotic symptoms and age at first hospitalization. The corresponding correlations for the male subjects were in the opposite direction and not statistically significant. For each pair, the correlations between age at onset of schizophrenia and age at puberty for male and female participants were significantly different. Figure 1 displays the relation between one of the onset definitions, age at first hospitalization, and age at puberty for female and male subjects. Regression lines display the negative relationship for females, whereas for males the relationship is much weaker and in the opposite direction.

As for the remaining variables, family history of schizophrenia was significantly and inexplicably positively correlated with age at first psychotic symptoms for female subjects but not for male subjects. None of the remaining correlations between measures of schizophrenia onset and puberty was statistically significant for male subjects or for female subjects.

To examine whether any of the additional variables accounted for the observed gender differences in the relation between age at onset of schizophrenia and age at puberty, we conducted a series of hierarchical regression analyses. The analyses were conducted for each of the three schizophrenia onset definitions in turn. For each set of regression analyses, a first block of predictors consisted of gender and age at onset of puberty. In the second block, the interaction term (i.e., the product of gender and age at puberty) was added. In the third block, family history was added. The fourth block of variables comprised the substance use variables along with the head injury and obstetric complication measures.

For each set of equations, the relationships were as predicted by the zero-order correlations. For age at first psychotic symptoms and age at first hospitalization, a significant interaction term indexed the gender differences in the relation between age at onset of schizophrenia and age at puberty. The addition of the remaining variables did not alter this pattern of results. In no case did the addition of variables to the regression equations change the observed pattern of relationship between gender, age at onset of puberty, and any of the schizophrenia onset variables.

For age at puberty there was one female outlier (17.0 years) and there were two male outliers (19.0 years). When the regression analyses were conducted without the data on these subjects, the regression models were not altered. In steps 3 and 4 of the regression analyses, the study group size was reduced as a result of missing data. The family history variable was missing two data points; therefore step 3 of each analysis was based on N=78. Missing data for obstetric complications reduced the group size to N=62 for step 4 of each analysis. When steps 1 and 2 were repeated for each analysis with use of the smallest group size (i.e., N=62 instead of N=80), the pattern of the results was not meaningfully changed.

As further investigation of the robustness of the results, we removed the data on the 13 female and six male subjects with diagnoses of schizoaffective disorder and reran all of the previous analyses. Neither the magnitude of the means and correlations nor the patterns of the correlation or regression results were meaningfully altered. Similarly, when the analyses were conducted only with data on the individuals whose mothers had participated in the study (females, N=24; males, N=33), the pattern of results was not altered.

DISCUSSION

As predicted, the results show a strong inverse relation between female puberty and age at onset of schizophrenia. There was no significant correlation for the male subjects, but the trend was in the opposite direction. There is accumulating evidence that 1) estrogens protect neurons from atrophy (10, 32–34), 2) estrogens enhance the efficacy of antipsychotics in schizophrenia (11), and 3) periods of elevated estrogen levels over the course of a woman’s menstrual cycle and life cycle correlate with attenuated psychotic symptoms, and vice versa (14, 35, 36). The delaying role of female puberty in age at onset of schizophrenia further demonstrates the putative protective action of estrogens in schizophrenia.

Zero-order correlations confirmed a significant inverse relation between age at first menstruation in women and age at both first hospitalization and first appearance of psychotic symptoms. There was the same relation with first appearance of odd behavior, but it was weaker. The effect of age at puberty was not confounded by any other predictive variables tested in the analysis. Neither alcohol use, drug use, head injury, obstetric complications, nor family history added significant predictive power to the model of age at onset for women or, for that matter, for men.

These findings suggest an association between pubertal hormones and delayed age at onset of schizophrenia in women but do not explain why the effect seems to work in the opposite direction for men. The start of puberty brings about more than hormonal changes. It marks the beginning of increasingly divergent psychosocial pathways that separate women and men at this critical time in their lives. Of course, the exact reasons why puberty seems to delay onset of schizophrenia in women and, perhaps, hasten it in men are unknown. This is of special interest in that postpubertal psychosocial stress in adolescent girls has, conversely, been implicated in the increased prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders in women (37)

If hormones are involved, estrogen’s protection against nerve cell loss and the preservation of neuronal connectivity may be crucial in delaying onset of schizophrenia. The surge of pubertal testosterone in men does not appear to confer the same advantage. Alternatively, female hormones may act indirectly by protecting women from behavioral tendencies that trigger illness. Such tendencies as studied in this investigation (substance abuse and risk taking, reflected by head trauma) had low prevalence, did not distinguish men and women, and showed no predictive association with age at onset of illness. A test of this indirect hypothesis would need to include many other variables.

There are, however, reasons to be cautious in interpreting these effects. These reasons relate to study group and method. The group was small, diagnoses were not elicited by standardized interviews, and schizoaffective disorder was included in the definition of schizophrenic illness. The interviewer was not blind to the hypothesis. The accuracy of patient and maternal recall can always be called into question in a retrospective design. Although subjects, relatives, and psychiatric records showed high concordance for information that was available from all three sources, corroboration was not available for every data point. Nevertheless, the results of this study lend credence to the theory that female hormones act on the developing brain to protect its integrity and delay the expression of psychosis. Clinically relevant ramifications are that the low estrogen levels that are present in women premenstrually, postpartum, postmenopausally, or secondary to the administration of many antipsychotic drugs are potentially deleterious to women with schizophrenia. Women may be at risk for preventable aggravation of psychosis during these periods. The increasing availability of selective estrogen modulators with high benefit-to-risk ratios is an avenue for future therapeutic investigation.

Received Aug. 28, 1998; revision received Dec. 9, 1998; accepted Dec. 22, 1998. From the National Human Genome Research Institute, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore; the Centre for Addictions and Mental Health, University of Toronto; and the Department of Psychiatry, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia. Address reprint requests to Dr. Seeman, Centre for Addictions and Mental Health, 250 College St., Toronto, ON M5T 1R8, Canada; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by the Medland Family Fund for schizophrenia research; University of Toronto Open Graduate Fellowships, 1996–1998; the Canadian Psychiatric Research Foundation; and the Bertha Rosenstadt Fund, University of Toronto.

|

|

FIGURE 1. Relationship Between Age at First Hospitalization and Age at Onset of Puberty for Female and Male Subjects With Schizophreniaa

aThe same relationship was evident between age at first psychotic symptoms and age at onset of puberty for the two sexes.

1. Castle DJ, Abel K, Takei N, Murray RM: Gender differences in schizophrenia: hormonal effects or subtypes? Schizophr Bull 1995; 21:1–12Google Scholar

2. Castle DJ, Murray RM: The epidemiology of late-onset schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1993; 19:691–700Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Häfner H, Riecher-Rössler A, an der Heiden W, Maurer K, Fatkenheuer B, Löffler W: Generating and testing a causal explanation of the gender difference in age at first onset of schizophrenia. Psychol Med 1993; 23:925–940Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Sartorius N, Jablensky A, Korten A, Ernberg G, Anker M, Cooper JE, Day R: Early manifestations and first contact incidence of schizophrenia in different cultures: a preliminary report on the initial evaluation phase of the WHO collaborative study on determinants of outcome of severe mental disorders. Psychol Med 1986; 16:909–928Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Woolley CS, Weiland NG, McEwen BS, Schwartzkroin PA: Estradiol increases the sensitivity of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells to NMDA receptor mediated synaptic input: correction with dendritic spine density. J Neurosci 1997; 17:1848–1859Google Scholar

6. Woolley CS, McEwen BS: Estradiol mediates fluctuation in hippocampal synapse density during the estrous cycle in the adult rat. J Neurosci 1992; 12:2549–2554Google Scholar

7. Smith SS: Female sex steroid hormones: from receptors to networks to performance—actions on the sensorimotor system. Prog Neurobiol 1994; 44:55–86Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Birge SJ: The role of estrogen in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1997; 48(suppl 7):S36–S41Google Scholar

9. Xu H, Gouras GK, Greenfield JP, Vincent B, Naslund J, Mazzarelli L, Fried G, Jovanovic JN, Seeger M, Relkin NR, Liao F, Checler F, Buxbaum JD, Chait BT, Thinakaran G, Sisodia SS, Wang R, Greengard P, Gandy S: Estrogen reduces neuronal generation of Alzheimer beta-amyloid peptides. Nat Med 1998; 4:447–451Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Toran-Allerand CD: The estrogen/neurotrophin connection during neural development: is co-localization of estrogen receptors with the neurotrophins and their receptors biologically relevant? Dev Neurosci 1996; 18:36–48Google Scholar

11. Häfner H, Behrens S, De Vry J, Gattaz WF: Oestradiol enhances the vulnerability threshold for schizophrenia in women by an early effect on dopaminergic neurotransmission. Eur Arch Psychiatr Clin Neurosci 1991; 241:65–68Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Hallonquist JD, Seeman MV, Lang M, Rector NA: Variation in symptom severity over the menstrual cycle of schizophrenics. Biol Psychiatry 1993; 33:207–209Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Gattaz WF, Vogel P, Riecher-Rössler A, Soddu G: Influence of the menstrual cycle phase on the therapeutic response in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 1994; 35:137–139Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Seeman MV: The role of estrogen in schizophrenia. J Psychiatry Neurosci 1996; 21:123–127Medline, Google Scholar

15. Fink G, Sumner BEH, Rosie R, Grace O, Quinn JP: Estrogen control of central neurotransmission: effect on mood, mental state, and memory. Cell Mol Neurobiol 1996; 16:325–344Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. DeQuardo JR, Carpenter CF, Tandon R: Patterns of substance abuse in schizophrenia: nature and significance. J Psychiatr Res 1994; 28:267–275Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Buckley P, Stack JP, Madigan C, O’Callaghan E, Larkin C, Redmond O, Ennis JT, Waddington JL: Magnetic resonance imaging of schizophrenia-like psychoses associated with cerebral trauma: clinicopathological correlates. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:146–148Link, Google Scholar

18. Verdoux H, Geddes JR, Takei N, Lawrie SM, Bovet P, Eagles JM, Heun R, McCreadie RG, McNeil TF, O’Callaghan E, Stöber G, Willinger U, Wright P, Murray RM: Obstetric complications and age at onset in schizophrenia: an international collaborative meta-analysis of individual patient data. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1220–1227Google Scholar

19. DeLisi LE, Bass N, Boccio A, Shields G, Morgenti C: Age of onset in familial schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:334–335Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Cohen J: Statistical Power Analyses for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988Google Scholar

21. First MB, Williams JBW, Spitzer RL: DTREE for Windows: The DSM-IV Expert. North Tonawanda, NY, Multi Health Systems, 1997Google Scholar

22. First MB, Opler LA, Hamilton RM, Linder J, Linfield LS, Silver JM, Toshav NL, Kahn D, Williams JBW, Spitzer RL: Evaluation in an inpatient setting of DTREE, a computer-assisted diagnostic assessment procedure. Compr Psychiatry 1993; 34:171–175Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Häfner H, Riecher-Rössler A, Fatkenheuer B, Maurer K, Meissner S, Löffler W, Patton G: Interview for the Retrospective Assessment of the Onset of Schizophrenia (IRAOS). Schizophr Res 1992; 6:209–223Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Maurer K, Häfner H: Methodological aspects of onset assessment in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1995; 15:265–276Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Gilger JW, Geary DC, Eisele LM: Reliability and validity of retrospective self reports of the age of pubertal onset using twin, sibling, and college student data. Adolescence 1991; 26:41–53Medline, Google Scholar

26. Casey VA, Dwyer JT, Coleman KA, Krall EA, Gardner J, Valadian I: Accuracy of recall by middle-aged participants in a longitudinal study of their body size and indices of maturation earlier in life. Ann Hum Biol 1991; 18:155–166Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Koo MM, Rohan TE: Accuracy of short-term recall of age at menarche. Ann Hum Biol 1997; 24:61–64Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Hambrecht M, Häfner H: Sensitivity and specificity of relatives’ reports on the early course of schizophrenia. Psychopathology 1997; 30:12–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Endicott J, Andreasen N, Spitzer RL: Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria, 3rd ed. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1978Google Scholar

30. Andreasen NC, Grove WM, Shapiro RW, Keller MB, Hirschfeld RM, McDonald-Scott P: Reliability of lifetime diagnosis: a multicenter collaborative perspective. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 38:400–405Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Lewis SW, Owen MJ, Murray RM: Obstetric complications and schizophrenia: methodology and mechanisms, in Schizophrenia: Scientific Progress. Edited by Schulz SC, Tamminga CA. New York, Oxford University Press, 1989, pp 56–68Google Scholar

32. Arimatsu Y, Hatanaka H: Estrogen treatment enhances survival of cultured fetal rat amygdala neurons in a defined medium. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 1986; 26:151–159Crossref, Google Scholar

33. Shugrue PJ, Dorsa DM: Gonadal steroids modulate the growth-associated protein GAP-43 (neuromodulin) mRNA in postnatal rat brain. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 1993; 73:123–132Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Sohrabji F, Miranda RC, Toran-Allerand CD: Estrogen differentially regulates estrogen and nerve growth factor receptor mRNAs in adult sensory neurons. J Neurosci 1994; 14:459–471Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Kendall RE, Chalmers JC, Platz C: Epidemiology of puerperal psychoses. Br J Psychiatry 1987; 150:662–673Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Riecher-Rössler A, Häfner H, Stumbaum M, Maurer K, Schmidt R: Can estradiol modulate schizophrenic symptomatology? Schizophr Bull 1994; 20:203–214Google Scholar

37. Seeman MV: Psychopathology in women and men: focus on female hormones. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1641–1647Google Scholar