Sustained Attention Deficit and Schizotypal Personality Features in Nonpsychotic Relatives of Schizophrenic Patients

Abstract

Objective: The authors investigated whether nonpsychotic relatives of schizophrenic probands have an elevated risk of deficits in sustained attention as measured by the Continuous Performance Test (CPT), whether such deficits are associated with specific factors of schizotypy, and whether poor CPT performance by probands predicts poor performance by their relatives. In addition, the heritability of CPT performance in the families of schizophrenic probands was estimated.Method: The study subjects were 60 schizophrenic probands, 148 of their first-degree relatives, 20 normal comparison probands, and 42 of the comparison probands’ first-degree relatives. Subjects completed undegraded and 25% degraded sessions of the CPT and were interviewed with use of the Chinese version of the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies. Subjects’ CPT sensitivity indexes, d′, were standardized against those of a community sample of 345 subjects, with adjustment for age, sex, and level of education.Results: On average, the d′ values of the relatives of schizophrenic probands were lower than those of the relatives of comparison probands but higher than those of schizophrenic probands. Lower sensitivity indexes among the relatives of schizophrenic patients were associated with the interpersonal dysfunction and disorganization factors of schizotypy but not the cognitive/perceptual factor. When schizophrenic probands were divided into two subgroups by a cutoff of –3.0 for adjusted z score on the CPT, the d′ values of relatives of probands with CPT deficits were lower than those of relatives of probands without deficits. The estimated heritability of performance on the CPT ranged from 0.48 to 0.62.Conclusions: Sustained attention deficit may be a genetic vulnerability marker for schizophrenia, and it may be more useful in linkage analysis than traditional phenotype definitions of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155: 1214-1220

Sustained attention deficit detected by the Continuous Performance Test (CPT) is a potential vulnerability marker for schizophrenia (1). Schizophrenic patients in various clinical and medication states (2, 3), those with schizotypal personality disorders (4), relatives of schizophrenic patients (5, 6), and nonclinical subjects with high schizotypy scores (7, 8) all exhibit poorer performance on the CPT than normal individuals. Despite the large number of previous investigations, the interpretation of CPT performance as a vulnerability marker for schizophrenia is still limited in three respects. First, transmission of CPT performance in the families of schizophrenic patients has been addressed in only a few studies of limited sample size (9, 10); second, the small number of comparison subjects in previous studies makes estimating the percentage of patients and their relatives who have sustained attention deficits difficult; and third, adjustment for the influence of demographic features on the CPT has not been adequate. A study of a large community sample (8) found that older age, female sex, and lower education level are associated with poorer CPT performance.

Sustained attention deficit is associated with negative symptoms (11-13) and thought disorders (11, 14, 15) among schizophrenic patients and, thus, may provide heuristic clues to the pathophysiology of schizophrenia (16). Among nonclinical populations, the latent structure of schizotypal personality features, or schizotypy, contains factors equivalent to those of schizophrenic symptoms (17, 18), e.g., negative (or interpersonal dysfunction), positive (or cognitive/perceptual dysfunction), and disorganized. Poorer CPT performance is associated with the negative factor (19, 20) and disorganization (20) but not with the positive factor (19, 20) of schizotypy. Thus, the usefulness of performance on the CPT as a vulnerability marker for schizophrenia would be enhanced if sustained attention deficit among nonpsychotic relatives of schizophrenic patients could be shown to be associated with specific schizotypal factors.

We investigated CPT performance and schizotypal personality features among nonpsychotic relatives of schizophrenic probands and relatives of comparison probands. CPT performance was standardized against a large community sample with adjustment for age, sex, and level of education. The hypotheses tested were that 1) the CPT performance of the relatives of schizophrenic probands is poorer than that of the relatives of comparison probands, 2) CPT performance is associated with interpersonal dysfunction and disorganization factors in the relatives of schizophrenic probands, and 3) poorer CPT performance of schizophrenic probands predicts poorer CPT performance of their relatives. The empirical heritability of CPT performance in the families of schizophrenic probands was also estimated.

METHOD

Sixty schizophrenic probands and 148 of their first-degree relatives, 20 comparison probands and 42 of their first-degree relatives, and 345 community subjects serving as the norm for CPT performance were included in this study. Only relatives 17 years of age or older were included. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects after complete description of the study.

The schizophrenic probands were selected from an ongoing prospective follow-up study for validation of the negative/non-negative subtyping of schizophrenia, the Multidimensional Psychopathology Group Research Projects. Since Aug. 1, 1993, patients consecutively admitted to the acute inpatient wards of three hospitals, National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei City Psychiatric Center, and the Provincial Tao-Yuan Psychiatric Center, have been included in the prospective follow-up study if they meet the DSM-III-R criteria for schizophrenic disorders and agree to participate. For the present study, the diagnoses were reevaluated at discharge by consensus among three senior psychiatrists using all information available from clinical observations, medical records, and key informants. All patients with a discharge diagnosis other than schizophrenia and patients with a history of physical illness or substance abuse that cast the diagnosis in doubt were excluded. Among 143 eligible schizophrenic patients, 60 patients agreed to let researchers approach their relatives. Among a total of 303 of their first-degree relatives, 257 were available (25 were dead, 13 were abroad, and eight were less than 17 years of age) and 158 (61.5%) were directly interviewed. Three relatives with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, one with schizophreniform disorder, one with mental retardation, and five other relatives who did not take the CPT were excluded from the study. Of the remaining 148 relatives, 79 were parents, 67 were siblings, and two were offspring of the probands.

The selection of the community subjects has been described in detail elsewhere (8). Briefly, 345 adults were systematically sampled from the 1993 and 1994 voter lists of Chinshan Township, which is a 60-minute drive north of Taipei. Approximately 65% of the prospective subjects who were selected and resided in Chinshan were successfully interviewed. Only subjects who did not have a diagnosis of psychosis or stroke and completed both a questionnaire and the CPT were included. For the present study, 20 normal comparison probands were selected from this sample by matching them to the age, sex, and education level of the first 20 schizophrenic probands. Among the 124 first-degree relatives of these comparison probands, 10 were dead and eight were less than 17 years of age. Of the remaining 106 relatives, 42 (39.6%) completed the test (nine were parents, 29 were siblings, and four were offspring).

Probands and first-degree relatives of both groups were interviewed with use of the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies (DIGS) (21). The Chinese version, DIGS-C, was translated by two psychiatrists (S.K.L. and C.-J.C.) and one psychiatric epidemiologist (W.J.C.). The DIGS contains a section of the modified Structured Interview for Schizotypy (SIS) (22), which was back-translated into English to ensure the accuracy of the translation. The DIGS-C interviews were carried out by six well-trained research assistants with majors in psychology or psychiatric nursing. They had received standardized psychiatric interview training for 4 weeks and completed six sessions of videotape reliability testing before participating in the data collection. The interviewers were not blind to the probands’ status, because providing relevant knowledge about schizophrenic probands was essential in motivating relatives to participate.

The axis I and axis II diagnoses of the study subjects were first assessed independently by three investigators (S.K.L., C.-J.C., and W.J.C.) by reviewing the DIGS-C records; then a consensus diagnosis was reached. Additional information, including copies of hospital records and information from the Family Interview for Genetic Studies (developed by the National Institute of Mental Health Genetics Initiative), was considered before a diagnosis was reached. Three levels of diagnoses according to DSM-III-R were possible: none, probable (the required number of criteria were met, but one item was near the criterion threshold), and definite.

The interrater reliability for the DIGS-C was assessed separately for axis I and axis II diagnoses in two sets of subjects. In the first set, 31 subjects (21 inpatients, four outpatients, and six normal subjects) were each interviewed by one physician while the other participants in the reliability study made ratings by viewing the videotapes. The kappas for the diagnoses of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression by the three physicians and two research assistants ranged from 0.86 to 0.93. In the second set, 13 subjects with at least one axis II diagnosis (six with schizotypal personality disorder, seven with paranoid personality disorder, and four with schizoid personality disorder; among them, four had two diagnoses simultaneously) and 14 subjects without any axis II diagnosis were each interviewed by one research assistant. The three physicians then read the DIGS-C records and made diagnoses independently. The kappas of their diagnoses were 0.72 for schizotypal personality disorder, 0.68 for paranoid personality disorder, and 0.90 for schizoid personality disorder. Five research assistants who had completed training re-rated the global ratings of the modified SIS section for these 27 subjects. The intraclass correlation coefficients for the global ratings of the modified SIS section ranged from 0.64 to 0.97.

The CPT

We used a CPT machine from Sunrise Systems (Pembroke, Mass.), version 2.20. The procedure has been described in detail elsewhere (13). Briefly, numbers from 0 to 9 were randomly presented for 50 msec each, at a rate of 1 per second. Each subject underwent two CPT sessions: the undegraded 1–9 task and the degraded 1–9 task. A total of 331 trials, 31 of them targets, were presented over a period of 5 minutes for each session. During the 25% degraded task session, a pattern of snow was used to toggle background and foreground dots so that the image was not distinct. The sensitivity index of CPT performance, d′, was derived from the hit rate and false alarm rate (1). The CPT was not administered until the schizophrenic patients were stabilized. Most of the other subjects took the CPT in interview rooms of hospitals or the Chinshan Health Station on the day of the DIGS-C interview; 13 subjects were tested during a home visit.

Data Analysis

We standardized the sensitivity index of CPT performance with adjustment for sex, age, and education as described by Saykin et al. (23). Briefly, the d′ was regressed on these covariates among the 345 normal subjects. Adjusted scores for a subject were then calculated with use of the regression coefficients for these covariates derived from the normal subjects. The residual of the regression was then standardized by the root mean error of the regression, defined as the adjusted z score for the sensitivity index. Comparisons among the three study groups were conducted by analysis of variance followed by post hoc pairwise tests with Scheffé’s correction for multiple comparisons. To adjust for within-family correlations in comparing the CPT performance of the relatives of the two groups, we applied generalized estimating equations with the assumption that probands were not matched (24). In choosing an appropriate cutoff point of d′ for genetic analysis, we calculated Risch’s λ coefficient (25). The empirical heritability of CPT performance was estimated from the regression of d′ of offspring on d′ of either one or two parents (26). For comparisons between two groups, we used Fisher’s exact test (two-tailed) for dichotomous variables and t tests (two-tailed) for continuous variables.

RESULTS

The demographic features of the schizophrenic probands were similar to those of the comparison probands (table 1). The raw score of d′ of the schizophrenic probands was lower than that of the comparison probands (for the undegraded CPT d′, t=–10.8, df=78, p=0.0001; for the degraded CPT d′, t=–11.7, df=72.5, p=0.001), as were their adjusted z scores (for the undegraded CPT d′, t=–10.6, df=70.2, p=0.001; for the degraded CPT d′, t=–11.2, df=69, p=0.0001). The relatives of the schizophrenic probands were on average 8.5 years older than the relatives of the comparison probands (t=3.1, df=188, p=0.003), but the two groups of relatives were similar in distribution of the sexes and in education. The mean d′ on the CPT was lower for the relatives of the schizophrenic probands than for the relatives of the comparison probands according to both the raw scores (for the undegraded CPT d′, t=–7.7, df=162.1, p=0.0001; for the degraded CPT d′, t=–10.5, df=155.5, p=0.0001) and the adjusted z scores (for the undegraded CPT d′, t=–8.0, df=185.6, p=0.0001; for the degraded CPT d′, t=–10.4, df=160.6, p=0.0001). These values for the comparison probands did not deviate from the norms. The differences in adjusted z score between the relatives of the two proband groups remained significant in regression analyses when we applied generalized estimating equations (z=6.6 for the undegraded CPT d′ and z=9.5 for the degraded CPT d′; each p<0.001).

We then calculated Risch’s λ values at a series of cutoff points on the basis of the adjusted z scores of the relatives of the schizophrenic probands versus those of the normal subjects. For d′ on the undegraded CPT, λ values at the cutoff points of –2.5, –3.0, and –3.5 were 9.6, 16.3, and 53.6, respectively. For d′ on the degraded CPT, λ values at the cutoff points of –2.5, –3.0, and –3.5 were 18.2, 130.3, and ∞, respectively. Because λ values at the cutoff point of –3.0 for both the undegraded and the degraded CPT d′ were greater than those of other schizophrenia spectrum phenotypes (discussed later), we defined deficit on the CPT as an adjusted z score less than or equal to –3.0. Among the schizophrenic probands, the frequency of d′ deficit ranged from 45% to 63% (table 1). The frequency of d′ deficit was higher among the relatives of the schizophrenic probands (19%–34%) than among the relatives of the comparison probands (0%).

Among the study groups, the mean d′ for both the undegraded and the degraded CPT was lowest in the group of schizophrenic probands. Relatives of the schizophrenic probands had an intermediate d′, while the comparison subjects (the probands and their relatives together) had the highest mean d′ (p<0.01, Scheffé’s test). The frequency of d′ deficit among the three groups showed the opposite tendency (Wald χ2=32.7 for the undegraded CPT d′ and Wald χ2=42.5 for the degraded CPT d′; df=1, p<0.0001, logistic regression).

Definite diagnoses of personality disorders among the relatives of the schizophrenic probands included schizotypal personality disorder (N=2), paranoid personality disorder (N=4), and schizoid personality disorder (N=2). One relative had both schizotypal and paranoid personality disorders. The adjusted z scores of d′ of these seven relatives (for the undegraded CPT, mean=–2.2, SD=2.7; for the degraded CPT, mean=–4.2, SD=3.1) were lower than those of the other relatives (mean=–1.3, SD=2.1, and mean=–2.5, SD=2.3, respectively), although the differences were not statistically significant (t=1.1, df=146, p=0.30, and t=1.7, df=141, p=0.10, respectively). When both definite and probable diagnoses were included, 19 relatives had one of these three diagnoses. Similarly, their adjusted z scores of d′ (for the undegraded CPT, mean=–1.7, SD=2.2; for the degraded CPT, mean=–3.2, SD=2.8) were lower than those of the remaining relatives (mean=–1.3, SD=2.1, and mean=–2.4, SD=2.2, respectively), although this difference was also not statistically significant (t=0.7, df=146, p=0.50, and t=1.2, df=141, p=0.20, respectively).

The global ratings on the modified SIS section were grouped a priori into three factors on the basis of previous confirmatory factor analysis studies (18, 20). For the three schizotypy factors, the d′ of the undegraded CPT (N=148) was correlated with interpersonal dysfunction (r=–0.27, p=0.001) and disorganization (r=–0.30, p=0.0008) but not cognitive/perceptual dysfunction (r=0.01, p=0.92). Similarly, the degraded CPT d′ of the relatives (N=143) was correlated with interpersonal dysfunction (r=–0.17, p=0.04) and disorganization (r=–0.22, p=0.001) but not cognitive/perceptual dysfunction (r=0.03, p=0.72).

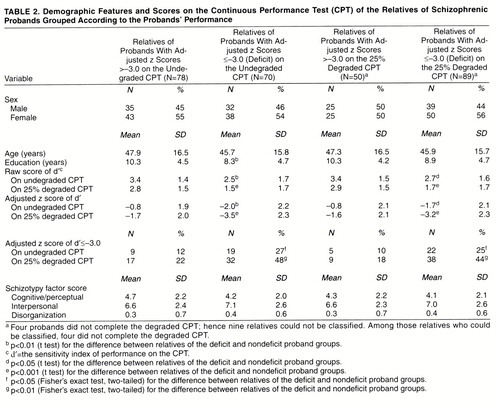

When the probands were classified into deficit and nondeficit subgroups, the demographic features of the relatives of nondeficit probands were not different from those of the relatives of deficit probands except in level of education, which reached statistical significance if subgrouping was based on probands’ undegraded CPT performance (t=2.4, df=146, p=0.02) (table 2). If probands’ performance on the undegraded CPT was used for subgrouping, the relatives of probands with a deficit had lower d′ on both the undegraded CPT (for raw score, t=3.2, df=146, p=0.002; for adjusted z score, t=3.4, df=146, p=0.0009) and the degraded CPT (for raw score, t=4.1, df=141, p=0.0001; for adjusted z score, t=4.3, df=141, p=0.0001). Similarly, if probands’ performance on the degraded CPT was used for subgrouping, the relatives of probands with a deficit had lower d′ on both the undegraded CPT (for raw score, t=2.9, df=146, p=0.005; for adjusted z score, t=2.8, df=146, p=0.007) and the degraded CPT (for raw score, t=3.7, df=141, p=0.0003; for adjusted z score, t=3.7, df=141, p=0.0004). The relatives of deficit probands also had a higher proportion of deficit on both the undegraded and the degraded CPT than did those of nondeficit probands. The differences in adjusted z score between the two subgroups of relatives remained significant in regression analyses using generalized estimating equations (z=2.37 for the undegraded CPT d′ and z=3.78 for the degraded CPT d′ when relatives were subgrouped according to probands’ undegraded CPT d′; z=2.03 for the undegraded CPT d′ and z=3.44 for the degraded CPT d′ when the relatives were subgrouped according to probands’ degraded CPT d′; all p values <0.04). However, there were no differences in schizotypy factors between these two subgroups of relatives when they were classified according to probands’ undegraded or degraded CPT d′ (all t values <1.3, df=146, p>0.20).

Among the relatives of schizophrenic probands, the sensitivity index of CPT performance of each parent was known in 10 families, while that of only one parent was known in another 18 families. The empirical heritability in the first type of family was estimated as 0.62 (SD=0.12) on the basis of undegraded CPT d′ scores and 0.57 (SD=0.28) on the basis of degraded CPT d′ scores. Empirical heritability in the second type of family was 0.48 (SD=0.18) on the basis of undegraded CPT d′ scores and 0.51 (SD=0.32) on the basis of degraded CPT d′ scores.

DISCUSSION

If deficit in performance on the CPT is a vulnerability marker for schizophrenia, similar deficits in sustained attention should be present in the nonpsychotic relatives of schizophrenic patients. On the other hand, since not every relative carries the genetic susceptibility, the mean magnitude of the deficit in the relatives of schizophrenic probands should be less than that in the schizophrenic probands themselves. This was in fact true in our study and in previous studies (6, 10). Also, the proportion of relatives with a deficit in CPT performance in our study was quite high. These percentages are higher than those for morbid risk of schizophrenia or schizophrenia-related personality disorders among the relatives of schizophrenic patients (27, 28). Comparing the genetic usefulness of some potential vulnerability indicators of schizophrenia, Faraone et al. (29) found that the λ values for the P300 latency measure, two assessments of schizotypal personality disorder, and two measures of neuromotor impairment were between 11 and 15, while the value for a composite attention deficit measure (including the CPT) was 30. Our data indicate that if a threshold of –3.0 for adjusted z score was used, the λ value was greater than 15 for the undegraded CPT and greater than 30 for the degraded CPT. Thus, the CPT performance deficit alone, when it is at a severe level, might be more useful than other schizophrenia spectrum definitions in linkage analysis.

Another concern in our choice of threshold is that the distribution of d′ scores among the normal group was skewed because of a ceiling effect. In the community sample, the proportion of subjects who reached the best allowable limit of d′ was 16.5% on the undegraded CPT and 4.4% on the degraded CPT (8). Thus, a stringent criterion at 3 SD below the population mean would render the impact of the ceiling effect negligible.

Performance on the CPT was correlated specifically with the interpersonal dysfunction and disorganization factors but not with the cognitive/perceptual factor of schizotypy in the relatives of the schizophrenic probands in our study. These results are slightly different from our findings in a community sample of 345 subjects (8), in which interpersonal dysfunction was significantly associated with lower degraded CPT performance only, while disorganization was significantly associated with lower undegraded CPT performance only. A possible explanation for this is that the current definition of schizotypy includes both “clinical” and “familial” schizotypes (30), and the community sample might have included many clinical cases, whereas the group of relatives was enriched with familial cases. Relatives with schizotypy-related personality disorders also tended to have lower d′ values than those without such disorders. This difference was not statistically significant, however, possibly because of the small number of relatives who met the diagnostic criteria.

The relationship between probands’ CPT performance and that of their relatives further supports the notion that performance on the CPT is a genetic vulnerability marker for schizophrenia. Schizophrenic probands with poorer CPT performance presumably should carry a higher genetic loading than those with better CPT performance, and their relatives should manifest such differences in CPT performance. When we divided the schizophrenic probands into deficit and nondeficit subgroups according to the adjusted z score of –3.0, their relatives’ CPT performance was consistent with this prediction. It is interesting that the magnitude of the difference in performance in the two subgroups of relatives, classified by probands’ undegraded or degraded CPT d′, was similar. It seems that an adjusted z score of –3.0 was stringent enough that it did identify schizophrenic probands with high genetic loading, regardless of the level of CPT difficulty. In contrast, schizophrenic probands’ CPT deficit failed to predict more schizotypal personality features in their relatives. This indicates that despite the moderate correlation between d′ and two schizotypal factors (interpersonal dysfunction and disorganization) observed among relatives, CPT deficit and schizotypy may be distinct traits.

Poor CPT performance thus appears to have potential as a genetic vulnerability indicator for schizophrenia. According to Meehl (31), what is inherited in schizophrenia is a neurophysiological defect called schizotaxia, which manifests as schizotypy in individuals with a normal upbringing. Comparing several neuropsychological tests, one study (32) found that the heritable component of neuropsychological dysfunction lies in attention deficit. Thus, the CPT may have detected such a schizotaxial defect among the relatives of schizophrenic patients in our study. Indeed, there appears to be a substantial genetic contribution to performance on the CPT, as shown by our heritability estimates, which lie between those of two previous studies that examined this issue. Wagener et al. (9) found only a moderate intergenerational correlation for the omission rate (i.e., 1 minus the hit rate) (r=0.12) and commission rate (i.e., false alarm rate) (r=0.13) between 25 schizophrenic patients and their mothers. Since schizophrenic patients’ deficits in sustained attention are more severe than those of their nonpsychotic relatives and tend to be the extreme within their families, including them in the estimations of correlation might have made the intergenerational correlations low. Grove et al. (10) studied the performance on a different version of the CPT of 61 nonpsychotic siblings of schizophrenic patients and found that the heritability of performance was 0.79. Since no parents were included in that study, common environmental factors shared by siblings might have contributed to the high estimate of heritability. To separate common environment from genetic factors, twin studies of CPT performance are warranted.

Received March 17, 1997; revisions received Dec. 5, 1997, and Jan. 26, 1998; accepted Feb. 5, 1998. From the Institute of Epidemiology, College of Public Health, and the Department of Psychiatry, College of Medicine, National Taiwan University.. Address reprint requests to Dr. Hwu, Department of Psychiatry, College of Medicine, National Taiwan University, 7 Chung-Shan South Road, Taipei 100, Taiwan. Supported by grants DOH83-HR-306, DOH84-HR-306, and DOH85-HR-306 from the National Health Research Institute, Taiwan; and grants NSC83-0412-B-002-310, NSC84-2331-B-002-187, and NSC85-2331-B-002-269 from the National Science Council, Taiwan.The authors thank the other research team members of the Multidimensional Psychopathology Group Research Projects, including Drs. Hung-Jung Chang, Hai Ho, Ping-Ju Chang, Shi-Chin Guo, Shian-Yuan Lan, Su-Kuan Lin, Fu-Chuan Wei, and Joseph J. Cheng, for the recruitment and evaluation of schizophrenic patients; collaborators of the NIMH Genetics Initiative for granting permission to translate the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies (DIGS) into Chinese; Drs. Ming T. Tsuang and Stephen V. Faraone for providing training material for the DIGS interview; and Dr. Li-Ling Tseng for her work in the second stage of translation of the DIGS.

|

|

1. Nuechterlein KH: Vigilance in schizophrenia and related disorders, in Handbook of Schizophrenia, vol 5: Neuropsychology, Psychophysiology and Information Processing. Edited by Steinhauer SR, Gruzelier JH, Zubin J. Amsterdam, Elsevier, 1991, pp 397–433Google Scholar

2. Orzack MH, Kornetsky C: Attention dysfunction in chronic schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1966; 14:323–327Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Wohlberg GW, Kornetsky C: Sustained attention in remitted schizophrenics. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1973; 28:533–537Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Harvey PD, Keefe RSE, Mitroupolou V, Dupre R, Roitman SL, Mohs RC, Siever LJ: Information-processing markers of vulnerability to schizophrenia: performance of patients with schizotypal and nonschizotypal personality disorders. Psychiatry Res 1996; 60:49–56Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Rutschmann J, Cornblatt B, Erlenmeyer-Kimling L: Sustained attention in children at risk for schizophrenia: report on a Continuous Performance Test. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1977; 34:571–575Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Mirsky AF, Yardley SL, Jones BP, Walsh D, Kendler KS: Analysis of the attention deficit in schizophrenia: a study of patients and their relatives in Ireland. J Psychiatr Res 1995; 29:23–42Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Lenzenweger MF, Cornblatt BA, Putnick M: Schizotypy and sustained attention. J Abnorm Psychol 1991; 100:84–89Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Chen WJ, Hsiao CK, Hsiao L-L, Hwu H-G: Performance of the Continuous Performance Test among community samples. Schizophr Bull 1998; 24:163–174Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Wagener DK, Hogarty GE, Goldstein MJ, Asarnow RF, Browne A: Information processing and communication deviance in schizophrenic patients and their mothers. Psychiatry Res 1986; 18:365–377Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Grove WM, Lebow BS, Clementz BA, Cerri A, Medus C, Iacono WG: Familial prevalence and coaggregation of schizotypal indicators: a multitrait family study. J Abnorm Psychol 1991; 100:115–121Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Nuechterlein KH, Edell ES, Norris M, Dawson ME: Attentional vulnerability indicators, thought disorder, and negative symptoms. Schizophr Bull 1986; 12:408–426Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Johnstone EC, Frith CD: Validation of three dimensions of schizophrenic symptoms in a large unselected sample of patients. Psychol Med 1996; 26:669–679Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Liu SK, Hwu H-G, Chen WJ: Clinical symptom dimensions and deficits on the Continuous Performance Test in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1997; 25:211–219Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Strauss ME, Buchanan RW, Hale J: Relations between attentional deficits and clinical symptoms in schizophrenic outpatients. Psychiatry Res 1993; 47:205–213Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Pandurangi AK, Sax KW, Pelonero AL, Goldberg SC: Sustained attention and positive formal disorder in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1994; 13:109–116Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Cornblatt BA, Keilp JG: Impaired attention, genetics, and the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1994; 20:31–46Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Vollema MG, van den Bosch RJ: The multidimensionality of schizotypy. Schizophr Bull 1995; 21:19–31Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Raine A, Reynolds C, Lencz T, Scerbo A, Triphon N, Kim D: Cognitive-perceptual, interpersonal, and disorganized features of schizotypal personality. Schizophr Bull 1994; 20:191–201Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Kendler KS, Ochs AL, Gorman AM, Hewitt JK, Ross DE, Mirsky AF: The structure of schizotypy: a pilot multitrait twin study. Psychiatry Res 1991; 36:19–36Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Chen WJ, Hsiao CK, Lin CCH: Schizotypy in community samples: the three-factor structure and correlation with sustained attention. J Abnorm Psychol 1997; 106:649–654Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Nurnberger JI Jr, Blehar MC, Kaufmann CA, York-Cooler C, Simpson SG, Harkavy-Friedman J, Severe JB, Malaspina D, Reich T, Collaborators From the NIMH Genetics Initiative: Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies: rationale, unique features, and training. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:849–859Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Kendler KS, Lieberman JA, Walsh D: The Structured Interview for Schizotypy (SIS): a preliminary report. Schizophr Bull 1989; 15:559–571Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Saykin AJ, Gur RC, Gur RE, Mozley PD, Mozley LH, Resnick SM, Kester DB, Stafiniak P: Neuropsychological function in schizophrenia: selective impairment in memory and learning. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:618–624Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Liang KY, Pulver AE: Analysis of case-control/family sampling design. Genet Epidemiol 1996; 13:253–270Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Risch N: Linkage strategies for genetically complex traits, II: the power of affected relative pairs. Am J Hum Genet 1990; 46:229–241Medline, Google Scholar

26. Khoury MJ, Beaty TH, Cohen BH: Fundamentals of Genetic Epidemiology. New York, Oxford University Press, 1993, pp 200–206Google Scholar

27. Gottesman II, Shields J: Schizophrenia: The Epigenetic Puzzle. Cambridge, England, Cambridge University Press, 1982Google Scholar

28. Kendler KS, McGuire M, Gruenberg AM, O’Hare A, Spellman M, Walsh D: The Roscommon Family Study, III: schizophrenia-related personality disorders in relatives. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:781–788Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Faraone SV, Kremen WS, Lyons MJ, Pepple JR, Seidman LJ, Tsuang MT: Diagnostic accuracy and linkage analysis: how useful are schizophrenia spectrum phenotypes? Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1286–1290Google Scholar

30. Kendler KS: Diagnostic approaches to schizotypal personality disorder: a historical perspective. Schizophr Bull 1985; 11:538–553Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Meehl PE: Schizotaxia revisited. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:935–944Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Harris JG, Adler LE, Young DA, Cullum CM, Rilling LM, Cicerello A, Intemann PM, Freedman R: Neuropsychological dysfunction in parents of schizophrenics. Schizophr Res 1996; 20:253–260Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar