Effect of Pindolol on Onset of Action of Paroxetine in the Treatment of Major Depression: Intermediate Analysis of a Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial

Abstract

Objective:The purpose of this study was to investigate the effect of pindolol to accelerate the onset of action of paroxetine in patients suffering from major depression.Method:Patients who met DSM-IV criteria for a nonpsychotic disorder, who had no previously treated episode of major depression episode, and who had a score of at least 18 on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale were randomly assigned, for the first 21 days, to treatment with paroxetine (20 mg/day) and either pindolol (5 mg t.i.d.) or placebo. Patients were evaluated with the Hamilton depression scale, the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, and Global Clinical Impression (CGI) on days 0 (baseline), 5, 10, 15, 21, 25, 31, 60, 120, and 180.Results:Intermediate analysis of the first month’s results for the first 100 patients (pindolol, N=50; placebo, N=50) was performed. At day 10 there were more improved patients (defined as patients with a maximum score of 10 on the Hamilton depression scale) in the pindolol plus paroxetine group (N=24; 48%) than in the placebo plus paroxetine group (N=13; 26%). At day 5 there was no statistically significant difference, and at day 15 and thereafter, the differences between the two groups disappeared. Hamilton depression scale scores were significantly lower on days 5 and 10 for the pindolol plus paroxetine group (mean=15.7, SD=5.3, and mean=11.7, SD=6.4, respectively) than for the placebo plus paroxetine group (mean=19, SD=5.9, and mean=14.7, SD=6.8); this was also true for Montgomery-Åsberg depression scale and CGI scores. Conclusions:The addition of pindolol to paroxetine treatment significantly accelerates the onset of therapeutic response in patients suffering from major depression. Nevertheless, the mechanism (pharmacodynamic or pharmacokinetic) of this beneficial effect remains unclear. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155: 1346-1351

Despite advances in major depression treatment (1), the problem of the delay of onset of therapeutic benefits remains approximately the same for all available antidepressants, i.e., 2 to 3 weeks (2). Most antidepressant drugs, in particular the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), increase the concentration of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT; serotonin) present in the synaptic cleft (3, 4). The increased levels of 5-HT will act on postsynaptic receptors as well as presynaptic receptors including 5-HT1A somatodendritic receptors, which exert negative feedback on the axon, reducing the release of new 5-HT into the cleft, thereby reducing the effect of SSRI antidepressant medication (5, 6). There is experimental evidence, with use of both microdialysis and electrophysiological techniques, which indicates that during treatment with SSRI medication, synaptic concentrations of 5-HT do not increase until after the 5-HT1A receptors are functionally desensitized (7-10). The 2 weeks that are thought to be necessary for desensitization to occur seem to coincide with the onset of antidepressant effects (6, 11, 12).

Pindolol is a nonselective liposoluble β-adrenergic antagonist that exerts weak sympathomimetic activities and acts also as a 5-HT1A receptor antagonist. It therefore follows that pindolol should interfere with the feedback effect and allow SSRI medication to increase synaptic concentrations of 5-HT more rapidly (6, 13). Two open therapeutic trials of limited size have shown that the association of pindolol with SSRI in the treatment of major depression produced a more rapid therapeutic response than administration of the SSRI alone in patients who were naive to SSRI treatment, as well as in patients who had been previously judged to be resistant to antidepressant SSRI treatment (14, 15). Nevertheless, these preliminary results were not initially confirmed by a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial conducted with 43 patients receiving fluoxetine associated with pindolol (2.5 mg t.i.d.) or placebo (16). Recently, two large controlled trials have concluded that the addition of pindolol to antidepressant treatment increases, in a prolonged manner, the effectiveness of two SSRIs (17, 18). This effect of pindolol was explained by a higher response rate in the pindolol group rather than by a hastening response to SSRIs in contrast with the experimental hypothesis supporting the initial use of pindolol in depression treatment (19).

The goal of this study was to test the effect of pindolol on the onset of action of paroxetine in patients suffering from major depression in a multicenter randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. To study its hastening effect, pindolol has been prescribed only for a short period in the early phase of a depressive episode when the effect of SSRIs is delayed. While the study is still ongoing, analysis of the first 100 patients has been performed as planned in the protocol. These partial results are presented in this report because they confirmed the promising effect of pindolol, but they are in contrast with previous studies on the nature of this effect (16-18).

METHOD

Patients

The study group consisted of patients recruited by a group of 20 psychiatrists of the Réseau de Recherche et d’Expérimentation Psychopharmacologique (northern part of France). The investigators were psychiatrists in private, public, and institutional practice and university hospital practice. The study was centralized by the Unité d’Evaluation of the Lille University Hospital (Lille, France), which was responsible for logistics, statistical analysis, and assessment of quality of the study.

Potential participants were male and female inpatients and outpatients between 18 and 65 years of age. We included patients who met DSM-IV criteria for a current unipolar, major depressive episode, nonpsychotic subtype, with a score of at least 18 on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (20). Exclusion criteria for the study were serious or unstable medical illness (in particular, cardiovascular disorders); a history of organic mental disorders or brain disorders, bipolar disorders, any psychotic disorders, active substance use disorders (including alcohol) within the last 12 months; history of adverse reactions to or intolerance of or nonresponse to paroxetine or pindolol; history of use of a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) within the past 15 days or lithium within the previous 6 months; pregnancy; or lactation. We also excluded patients currently taking any type of cardiac antiarrhythmic treatment, verapamil, diltiazem, bepridil, or alprazolam. If the patient had been taking an anxiolytic drug other than alprazolam before entering the study, he or she was allowed to continue at the same dose that was taken before the patient received paroxetine; if a new prescription of an anxiolytic was necessary, oxazepam (up to 100 mg/day) was prescribed.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Lille University Hospital. Before inclusion in the study, all patients completed a written informed consent form after the study protocol had been fully explained, in accordance with French law.

Procedure

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-design, 6-month study, we compared pindolol to placebo, in association with paroxetine, for the first 3 weeks of the 6-month treatment period of a major depressive episode. All eligible patients received paroxetine in one daily dose (20 mg/day) for the entire 6 months of the study period. On the same day that they started paroxetine treatment, patients were randomly assigned to one of two parallel treatment groups receiving placebo or pindolol. Randomization was performed by an independent center, generated by tables of random numbers, and stratified by participating investigators to allocate treatment by blocks of four. Pindolol, as well as placebo, was given three times a day for the first 21 days of treatment (15 mg/day) and was then tapered to twice a day for 4 days (10 mg/day) and once a day for 3 days (5 mg/day) and was then stopped. The total length of pindolol treatment was 28 days.

Clinical Assessment

Before inclusion in the study, patients underwent standard clinical assessment comprising a psychiatric evaluation, structured diagnostic interview, and medical history to verify inclusion and exclusion criteria. The structured diagnostic interview used was the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (21). Sociodemographic data collected included gender, age, inpatient or outpatient status, past history of depressive episode, response to previous antidepressant treatment, current anxiety disorder, and use of anxiolytic treatment.

During the study, depressive symptoms were assessed at baseline (day 0) with the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (minimum score=0; maximum score=52) and with the 10-item Montgomery-Åsberg depression scale (minimum score=0; maximum score=60) (22). Items on the Hamilton depression scale were grouped in different subscales to analyze the nature of symptoms improved by the addition of pindolol, as follows: depression (items 1, 2, 7, 8, 10, and 13), suicide (item 3), and anxiety (items 9, 11, 15, and 16) (23). Global improvement was assessed with the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) (24), a 7-point scale (1=very much improved; 4=no change; 7=very much worse). The different scales were administered by the blind evaluators on days 5, 10, 15, 21, 25, 31, 60, 120, and 180. The repetitive evaluations for the first 2 weeks were performed to assess the specific effect of pindolol on the onset of action of paroxetine. Evaluations at days 21, 25, and 31 were performed to verify the lack of withdrawal effect or maintenance of improvement; evaluations at days 60, 120, and 180 were performed to assess long-term evolution of the depressive episode. Each evaluation was performed at the foreseen date with a window of 2 days during the first month and of 4 days at the subsequent dates. In addition, adverse experiences were recorded at each visit. The Hamilton depression scale and Montgomery-Åsberg depression scale interviews were all conducted by the 20 psychiatrists of the Réseau de Recherche et d’Expérimentation Psychopharmacologique, who were fully trained in the use of these instruments through live and videotaped interviews. For one patient, each evaluation was performed by the same investigator. Although interrater reliability in the use of the two scales was not formally assessed, participating clinicians established consensus through repeated interrater reliability sessions.

Statistical Analysis

The comparability of the patients in the two groups (pindolol plus paroxetine and placebo plus paroxetine) was tested by chi-square analysis on qualitative data and by Student’s t test for continuous measures. All analyses have been performed in intention-to-treat, i.e., in all the patients randomly assigned to either treatment condition, including those who failed to complete the study. Intermediate analysis of the first month’s results for the first 100 patients was planned to screen the pindolol effect on the onset of action of paroxetine. Experimental and clinical rationales for the use of pindolol have suggested that the effect of pindolol is to hasten the SSRI effect. Thus, the hypothesis-driven analysis was that the expected date of acceleration would be during the first 2 weeks of treatment, which explained the choice of frequent evaluations during this period. Beyond the third week of treatment, the interest of analysis was only to test whether differences in improvement were maintained or disappeared, despite the lack of a hypothesis supporting such an effect. The aim of analysis was to evaluate the difference between pindolol and placebo in onset of action of paroxetine, rather than evaluate the long-term effect of the two drug associations—pindolol plus paroxetine and placebo plus paroxetine—on depression because all patients received paroxetine, a treatment known to be effective in depression, with a delay of 2 or 3 weeks. These hypotheses concerning the effect of pindolol support the use of individual tests at each point.

The main endpoint of the study was remission, and the depression of the patients with a maximum score of 10 on the Hamilton depression scale was classified as remitted (25). Among the patients who did not complete the study until day 31, we considered as remitted the depression of those patients who dropped out the study with a maximum score of 10 on the Hamilton depression scale, without adverse effect. The other patients were classified as unsuccessful patients. This comparison was performed through use of a chi-square analysis, with Yates’s correction, at each point until day 31.

To determine precisely the effect of pindolol during the first 2 weeks of paroxetine treatment, we compared the severity of depression (evaluated by scores on the Hamilton depression scale and its subscales and on the Montgomery-Åsberg depression scale) and global improvement (evaluated by CGI scores) (expressed as means and standard deviations) in the pindolol plus paroxetine and placebo plus paroxetine groups at each point in the first 2 weeks. All the comparisons were performed at days 5, 10, and 15 by using Student’s t test for continuous measures. All statistical tests were performed (P. Devos, Unité d’Evaluation) with SAS software (Cary, N.C.), and statistical significance was set at p≤0.05.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Between June 1, 1995, and May 31, 1996, 112 patients were recruited, and intermediate analysis was performed on the first 100 patients for whom results were available until day 31. These 100 patients receiving paroxetine (20 mg/day) were randomly assigned to pindolol (N=50) or to placebo (N=50). Patients randomly assigned, respectively, to pindolol or placebo were comparable for several demographic and clinical characteristics: age (mean=40 years, SD=11, versus mean=44, SD=10), gender (33 women and 17 men versus 37 women and 13 men), past depressive episode (55% versus 58%), past unsuccessful treatment of depression (18% versus 18%), current anxiety disorder (43% versus 43%), current anxiolytic treatment (65% versus 62%), hospitalization for current depressive episode (45% versus 44%), baseline Hamilton depression scores (mean=24.2, SD=3.3, versus mean=24.1, SD=3.5), and baseline Montgomery-Åsberg depression scores (mean=30.4, SD=4.5, versus mean=30.6, SD=4.8).

Among the 100 patients, 20 (pindolol=10; placebo=10) had dropped out of the study before day 31. Five patients were withdrawn from the study because of side effects (pindolol=two; placebo=three). Adverse effects were nausea (one patient), drowsiness (one patient), hypotension (one patient), and hepatitis (two patients). Of the 15 remaining patients, eight dropped out of the study because of lack of response to treatment (pindolol=three; placebo=five), two because of early relapse of depressive symptoms (one in each group), and five because of improvement and patient unwillingness to continue treatment (pindolol=four; placebo=one). Among the five improved patients, the depression of four was classified as remitted (pindolol=three; placebo=one).

Depression Remission

Figure 1 shows the effect of pindolol treatment on remission of depressive episode over time for the first month of paroxetine treatment, for all patients randomly assigned to pindolol (N=50) or placebo (N=50). At day 5, there was no significant difference in the percent of patients with remitted depression in the pindolol plus paroxetine group (12%) and placebo plus paroxetine group (6%). At day 10, the proportion of patients with remitted depression (N=24 of 50; 48%) in the pindolol plus paroxetine group was significantly higher than that (N=13 of 50; 26%) in the placebo plus paroxetine group. At day 15 and thereafter, there were no significant differences between the two groups. At day 31 the proportion of patients with remitted depression was 76% in the pindolol plus paroxetine group and 70% in the placebo plus paroxetine group; the difference between the groups was not significant.

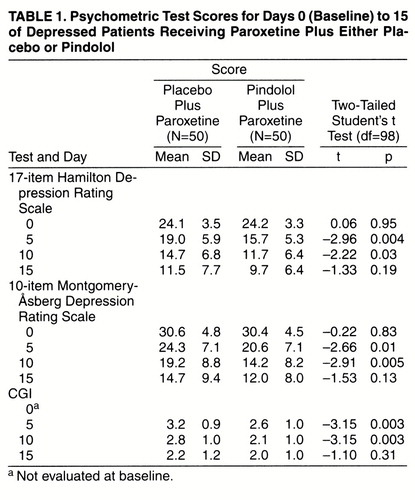

Analysis of global improvement with the CGI pointed out the effect of pindolol in the early phase of paroxetine treatment (table 1). At days 5 and 10 CGI scores were significantly lower in the pindolol plus paroxetine group than in the placebo plus paroxetine group. At day 15 CGI scores were not significantly different in the two groups.

Depression Severity

Changes in the level of severity of depression, as measured from days 0 to 15 by both the Hamilton and Montgomery-Åsberg depression scales, are presented in table 1. Hamilton depression scale scores were significantly lower in the pindolol plus paroxetine group than in the placebo plus paroxetine group at both days 5 and 10. At day 15 there was no significant difference between the two groups. The same pattern was seen for the Montgomery-Åsberg depression scale for the pindolol plus paroxetine and placebo plus paroxetine groups at both days 5 and 10. At day 15 there was no significant difference between the two groups.

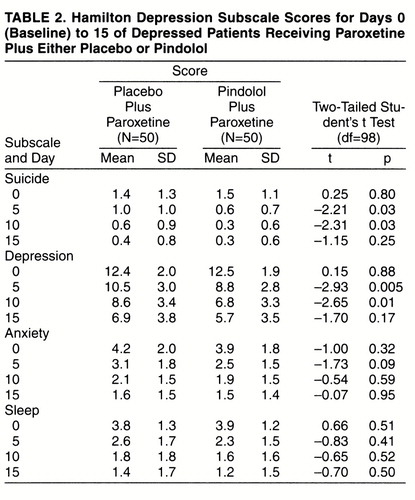

Table 2 shows the mean scores for the subscales of the Hamilton depression scale from days 0 to 15. Significant differences between the pindolol plus paroxetine and placebo plus paroxetine groups were found at both days 5 and 10 for the depression and suicide subscales but not for the anxiety and sleep subscales. Depression subscale scores were significantly lower with pindolol plus paroxetine than with placebo plus paroxetine at both days 5 and 10. Scores on the suicide subscale were significantly lower in the pindolol plus paroxetine group than in the placebo plus paroxetine group at day 5 and at day 10. At day 15 there was no significant difference between pindolol plus paroxetine and placebo plus paroxetine for all subscales.

DISCUSSION

Intermediate analysis at the end of the first month of treatment of the first 100 patients included in this study indicates that the addition of pindolol significantly accelerates the onset of response to paroxetine treatment in patients suffering from major depression. By day 10 of treatment, the percent of patients with clinical improvement significantly increased, by almost twofold, in the pindolol plus paroxetine group, while scores on the Hamilton depression scale, Montgomery-Åsberg depression scale, and CGI were significantly lower on days 5 and 10 in the pindolol plus paroxetine group. The number of patients with remitted depression in the two groups merged on day 15 and thereafter followed the same improvement course until day 31. The placebo group responded to treatment within the usual 2-week delay reported in standard SSRI studies, indicating that there was no particular bias in the recruitment of patients. The proportion of successful therapeutic results in this study is slightly higher than the 60% to 70% usually observed in studies of antidepressant drugs, which might in part be a result of the frequency of visits at the beginning of the study (days 0, 5, 10, 15, 21, 25, and 31), during which a supportive psychotherapeutic effect might have come into play.

Chemical blocking of β-receptors is widely used in psychiatry for problems as diverse as antipsychotic drug-induced akathisia and social phobia anxiety disorder (26, 27). Although β-blockers can partially mimic a small antidepressant effect through their antianxiety properties (27), our data suggest that this effect alone is not responsible for pindolol-induced improvement, because anxiety was not predominantly improved by pindolol plus paroxetine while depressive symptoms were clearly improved. The drug association of pindolol plus paroxetine improved psychic anxiety, as shown by changes in the score of this item in our study. Nonetheless, the significance of this item remains controversial because it is considered by some authors as a depressive symptom and by others as an anxiety symptom (23). Although many antidepressants down-regulate β-adrenergic receptors, there is no evidence that β-adrenergic antagonists induce any type of antidepressant effect by themselves, but, rather, can induce depressive symptoms (28). The lack of antidepressant activity in this class of drugs was also pointed out clearly in Blier and Bergeron’s work testing propranolol (15). There is, however, a certain heterogeneity concerning pharmacological properties within the β-adrenergic antagonist class, and, as a result, pindolol is known to have a higher affinity for 5-HT1A receptors that propranolol (29).

A more rapid onset of action of SSRIs by pindolol addition has been reported in two clinical trials (17, 18), while in another one (16), the authors failed to find any difference because of a lack of sufficiently frequent assessment in the first 2 weeks of treatment. Tome et al. (18) reported a significant acceleration of onset of action of paroxetine observable from day 4 in a group receiving pindolol (7.5 mg t.i.d. for 6 weeks). In their study of fluoxetine and pindolol (7.5 mg t.i.d. for 6 weeks), Pérez et al. (17) reported that the number of days to reach sustained response was lower in the fluoxetine and pindolol group than in the fluoxetine and placebo group (median=19 versus 29 days). The results concerning onset of action in our study are apparently in accordance with those of these and previous studies, while we used a higher dose and a shorter period of pindolol treatment. However, there is a discrepancy in the long-term effect of the addition of pindolol. In the study by Tome et al. (18), patients originally treated with pindolol showed better outcome at week 24 than patients taking paroxetine alone. In the study by Pérez et al. (17), the difference between pindolol and placebo in the cumulative percentage of patients with a sustained response was maintained until the end of the 6-week period. Moreover, there was no difference in time-to-onset of clinical improvement when only patients with sustained response were considered. These results might suggest that the more rapid onset of action of SSRIs would be related to a superior outcome in depression when pindolol is added. The differences in results could be explained by differences in length of pindolol treatment period. Nevertheless, if it is true that prolonged pindolol treatment leads also to prolonged enhancement of the effect of SSRIs, the mechanism of action of pindolol remains unclear and must be discussed.

From a pharmacodynamic point of view, our data emphasize the hypothesis of a presynaptic mechanism, e.g., an inhibition of 5-HT1A somatodendritic receptors by pindolol. Experimental evidence, with use of microdialysis techniques, suggests that pindolol acts preferentially on somatodendrite 5-HT1A autoreceptors to inhibit the negative feedback effect of 5-HT following the increase of 5-HT levels in the synaptic cleft as a result of local SSRI activity (30, 31). While it is clear that pindolol causes a functional blockade of 5-HT1A receptors (therefore including pre- or postsynaptic receptors), the waning of the feedback effect of 5-HT1A receptor stimulation after several days of SSRI treatment is not yet clearly understood, in part because it has not been consistently observed. There is still much discussion as to whether the density or the sensitivity of these receptors is affected by chronic SSRI administration (32). It has been suggested that SSRIs may also induce a decrease in the number of neuronal 5-HT carriers, leading to a long-term decrease in 5-HT reuptake (33). Postsynaptic adaptive mechanisms could also be possible, as suggested by prolonged enhancement of SSRI effects by pindolol when it is administered for 6 weeks (17, 18), as well as by results obtained in some treatment-resistant patients after pindolol addition (15). It remains unknown whether there is an enhanced activation of certain 5-HT postsynaptic receptors or whether long-term adaptive changes in limbic and cortical areas are also required. The mechanism of action of pindolol could be more complex than initially thought, with both presynaptic action explaining acceleration of onset of action and postsynaptic action explaining the higher rate of response when pindolol treatment is prolonged. Moreover, pindolol is often considered a “dirty drug,” meaning that the regulation of 5-HT receptors that it induces is complex and multifaceted. A pharmacokinetic interaction (i.e., increase in the plasma levels of paroxetine induced by pindolol) cannot be excluded, although it has not been confirmed in another study using fluoxetine (17). Nevertheless, these aspects were not investigated in this clinical study.

Whereas much has yet to be done to explain the mechanisms (pharmacodynamic or pharmacokinetic) involved, the results of this preliminary report strongly suggest that the association of pindolol with an SSRI will accelerate the therapeutic response to antidepressants, by more rapid improvement in depressive symptoms. The choice of the SSRI used remains to be precisely determined in relationship with differences in pharmacological profiles of SSRIs. Moreover, in view of two recent studies, it will also be necessary to precisely determine if this acceleration cannot be associated with an enhancement of response to SSRIs when pindolol treatment is prolonged.

Received March 12, 1997; revisions received Dec. 17, 1997, and Jan. 22 and March 19, 1998; accepted April 23, 1998. From the Réseau de Recherche et d’Expérimentation Psychopharmacologique (REPP) and Unité d’Evaluation, Centre Hospitalier et Universitaire, Lille, France. Members of the REPP are P. Thomas (general secretary), J.Y. Alexandre, R. Bordet, J. Catteau, C. Cyran, T. Danel, J. Debieve, J.P. Dumon, P. Dumont, B. Dupuis, D. Duthoit, D. Dutoit, C. Geraud, N. Lalaux, F. Lanvin, F. Lebert, J. Louvrier, J.P. Meaux, P.J. Parquet, C. Plumecocq, B. Scottez, D. Servant, C.E. Thomas, E. Trinh, G. Vaiva, J. Vignau, and A. Vincent.. Address reprint requests to Dr. Bordet, Service de Pharmacologie Hospitalière, Centre Hospitalier Regional Universitaire de Lille, 59045 Lille, France; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by grants from the Delegation à la Recherche du Centre Hospitalier et Universitaire de Lille (France).Pindolol was provided by Sandoz Pharmaceuticals. As principal investigator, Dr. Dupuis assumes full responsibility for the overall content of this article.

|

|

1. Boyer WF, McFadden GA, Feighner JP: The efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in depression, in Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors. Edited by Feighner JP, Boyer WF. Chichester, England, John Wiley & Sons, 1991, pp 89–108Google Scholar

2. Blier P, de Montigny C: Current advances and trends in the treatment of depression. Trends Pharmacol Sci 1994; 15:220–226Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Blier P, De Montigny C, Chaput Y: Modifications of the serotonin system by antidepressant treatments: implications for the therapeutic response in major depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1987; 7:24S–35SCrossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Hyttel J: Pharmalogical characterization of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1994; 9(suppl 1):19–26Google Scholar

5. Hoyer D, Clarke ED, Fozard J, Hartig P, Graeme M, Mylecharane E, Saxena P, Humphrey P: International Union of Pharmacology classification of receptors for 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin). Pharmacol Rev 1994; 46:157–203Medline, Google Scholar

6. Artigas F, Romero L, de Montigny C, Blier P: Acceleration of the effect of selected antidepressant drugs in major depression by 5-HT1A antagonists. Trends Neurosci 1996; 19:378–383Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Chaput Y, de Montigny C, Blier P: Effects of a selective 5-HT reuptake blocker, citalopram, on the sensitivity of 5-HT auto-receptors: electrophysiological studies in the rat brain. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 1986; 333:342–348Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Bel N, Artigas F: Chronic treatment with fluvoxamine increases extracellular serotonin in frontal cortex but not in raphe nuclei. Synapse 1993; 15:243–245Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Fuller RW: Uptake inhibitors increase extracellular serotonin concentration measured by brain microdialysis. Life Sci 1994; 55:163–167Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Rutter JJ, Gundlah C, Auerbach SB: Increase in extracellular serotonin produced by uptake inhibitors is enhanced after chronic treatment with fluoxetine. Neurosci Lett 1994; 171:183–186Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Heninger GR, Charney DS: Mechanism of action of antidepressant treatment: implication for the etiology and treatment of depressive disorders, in Psychopharmacology: The Third Generation of Progress. Edited by Meltzer HY. New York, Raven Press, 1987, pp 535–544Google Scholar

12. De Montigny C, Chaput Y, Blier P: Classical and novel targets for antidepressant drugs: new pharmacological approaches to the therapy of depressive disorders. Int Acad Biomed Drug Res 1993; 5:8–17Google Scholar

13. Bel N, Romero L, Celada P, de Montigny C, Blier P, Artigas F: Neurobiological basis for the potentiation of the antidepressant effect of 5-HT reuptake inhibitors by the 5-HT1A antagonist pindolol. Monit Mol Neurosci 1994; 6:209–210Google Scholar

14. Artigas F, Perez V, Alvarez E: Pindolol induces a rapid improvement of depressed patients treated with serotonin reuptake inhibitors (letter). Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:248–251Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Blier P, Bergeron R: Effectiveness of pindolol with selected antidepressant drugs in the treatment of major depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1995; 15:217–222Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Berman RM, Darnell AM, Miller HL, Anand A, Charney DS: Effect of pindolol in hastening response to fluoxetine in the treatment of major depression: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:37–43Link, Google Scholar

17. Pérez V, Gilaberte I, Faries D, Alvarez E, Artigas F: Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of pindolol in combination with fluoxetine antidepressant treatment. Lancet 1997; 349:1594–1597Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Tome MB, Isaac MT, Harte R, Holland C: Paroxetine and pindolol: a randomised trial of serotoninergic autoreceptor blockade in the reduction of antidepressant latency. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1997; 12:81–89Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Bordet R, Thomas P, Dupuis B: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors plus pindolol (letter). Lancet 1997; 350:289Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: User’s Guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

22. Montgomery SA, Åsberg M: A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry 1979; 134:382–389Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Bech P, Allerup P, Gram LF, Reisby N, Rosenberg R, Jacobsen O, Nagy A: The Hamilton depression scale. Evaluation of objectivity using logistic models. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1981; 63:290–299Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Conners CK, Barkley RA: Rating scales and checklists for child psychopharmacology. Psychopharmacol Bull 1985; 21:809–843Medline, Google Scholar

25. Hirschfeld RMA: Guidelines for the long-term treatment of depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55(Dec suppl):61–69Google Scholar

26. Dumon J-P, Catteau J, Lanvin F, Dupuis BA: Randomized, double-blind, crossover, placebo-controlled comparison of propranolol and betaxolol in the treatment of neuroleptic-induced akathisia. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:647–650Link, Google Scholar

27. Bailly D: The role of beta-adrenoreceptor blockers in the treatment of psychiatric disorders. CNS Drugs 1996; 5:115–136Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Avorn J, Everitt DE, Weiss S: Increased antidepressant use in patients prescribed β-blockers. JAMA 1986; 255:357–360Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Tricklebank MD, Forler C, Fogard JR: The involvement of subtypes of the 5-NT1 receptor and of catecholaminergic systems in the behavioral response to 8-hydroxy-2-(di-n-propylamino) tetralin in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol 1984; 106:271–282Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Artigas F: 5HT and antidepressants: new views from microdialysis studies. Trends Pharmacol Sci 1993; 15:262–263Crossref, Google Scholar

31. Hjorth S: Serotonin 5HT1A autoreceptor blockade potentiates the ability of the 5-HT reuptake inhibitor citalopram to increase nerve terminals output of 5-HT in vivo: a microdialysis study. J Neurochem 1993; 60:776–779Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Kreiss DS, Lucki I: Desensitization of 5-HT1A autoreceptors by chronic administration of 8-OH-DPAT. Neuropharmacology 1992; 31:1073–1076Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Pineyro G, Blier P, Dennis T, De Montigny C: Desensitization of the neuronal 5-HT carrier following its long-term blockade. J Neurosci 1994; 14:3036–3047Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar