The Orphans of Eritrea: Are Orphanages Part of the Problem or Part of the Solution?

Abstract

Objective:This study compared the mental health and cognitive development of 9- to 12-year-old Eritrean war orphans living in two orphanages that differed qualitatively in patterns of staff interaction and styles of child care management. Method:The directors and several child care workers at each institution were asked to complete staff organization and child management questionnaires. The psychological state of 40 orphans at each institution was evaluated by comparing their behavioral symptoms and performance on cognitive measures. Results:Orphans who lived in a setting where the entire staff participated in decisions affecting the children, and where the children were encouraged to become self-reliant through personal interactions with staff members, showed significantly fewer behavioral symptoms of emotional distress than orphans who lived in a setting where the director made decisions, daily routines were determined by explicit rules and schedules, and interactions between staff members and the children were impersonal.Conclusions:When orphanages are the only means of survival for war orphans, a group setting where the staff shares in the responsibilities of child management, is sensitive to the individuality of the children, and establishes stable personal ties with the children serves the emotional needs and psychological development of the orphans more effectively than a group setting that attempts to create a secure environment through an authoritative style of management with explicit rules and well-defined schedules. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155: 1319-1324

There is general agreement that unaccompanied children placed in institutional settings at a young age and for long periods are at greatly increased risk for serious psychopathology in later life. From this agreement has emerged the implicit generalization that extended institutional care is always harmful and should therefore be avoided if any other options are available (1-3). However, this generalization is often irrelevant in war-torn Third World countries, where the large majority of unaccompanied children and orphans are now concentrated (4-6) and where adoption and foster care are often culturally unacceptable and logistically unrealistic solutions (7, 8). Under such conditions it becomes a question of considerable clinical importance to determine what styles of child care in institutional settings will best meet the emotional needs of orphans and foster their cognitive and psychological development.

Almost no systematic studies have been carried out during the past five decades to address this question, largely because nearly all orphanages in industrial nations have been closed and replaced by adoption and foster care (9). Yet in Third World countries, orphanages are often the only viable means of survival for thousands of orphans. To reopen the question, we therefore compared the social organization of two orphanages that were organized according to qualitatively different styles of child management as well as the psychological status of orphans in each institution. The specific aim was to examine what effect, if any, the social structure of the two orphanages had on the emotional well-being of the orphans. The study was conducted in Eritrea, a small country on the Horn of Africa, with a population of 3 million persons who are engaged in a massive effort of social and economic reconstruction after a 30-year war with Ethiopia. The war had destroyed the entire infrastructure except the towns and cities under Ethiopian occupation and exhausted the country’s meager material resources (10).

A survey conducted by the Eritrean Department of Social Affairs (now the Ministry of Labour and Human Welfare) indicated that in 1991, there were at least 100,000 unaccompanied children under 14 years of age in Eritrea, of whom 10,000 had lost both parents, while the others had a living parent who could not support them (11). The Ministry of Labour and Human Welfare therefore implemented a comprehensive program to create suitable environments of long-term care for the 10,000 neediest children who had lost both parents. The keystone of the program was the reuniting of orphans with relatives who were able to accept an additional child despite the economic hardships it might impose. For orphans who could not be reunited, the ministry planned to build a number of small group homes (11).

By the end of 1997, over 8,000 of the 10,000 orphans had been reunited with relatives, but there had been no funds to build the first small group home until 1997. Five to 10 additional group homes are planned, but because they will not be completed for several years, the remaining 1,000–2,000 orphans will have to continue living in one of the orphanages. This historical reality motivated the study to determine in what ways the remaining orphanages might be reorganized to provide orphans with the best possible social environment in spite of very limited resources.

METHOD

The two orphanages selected for comparison are identified in this report as orphanages A and B. Orphanage A accommodated 450 children from 5 to 17 years of age and was located in a large urban center. The youngest children slept and lived together in one large dormitory; older orphans, grouped by chronological age, lived in separate dormitories. One-half of the current residents had lived there throughout the war, while the others had been transferred from orphanages in the base camps at the Solomuna Orphanage and Zero School after the war (12-14). The children attended nearby public schools, where they mixed freely with town children, who sometimes invited them to their homes after school or during vacations.

Orphanage B had room for 200 children from 5 to 16 years of age and was located in a rural setting near a large town. About one-half of the current residents had also lived there throughout the war, while the others had been transferred from the base camps after the war. The ages of the children in each dormitory were deliberately mixed so that the older children could help the younger ones with daily chores and school work. The children attended public school in town and mixed freely with town children. The ratio of staff members to children was about the same in the two institutions (about 17 children per staff member).

While the war was in progress, the major factor determining whether orphans would be assigned to orphanage A or B was the constant changes in the battle fronts. After the war, the children who had been relocated from the base camps were assigned to either orphanage on a space-available basis. Although there was no evidence of any systematic biases in the assignment of children to either orphanage, it was difficult to control for all factors that might have influenced the assignments.

Because the majority of children in both orphanages were in the age range from 9 to 12 years, study participants were selected from this age group. Every fourth name from an alphabetical list of all children in each institution who were in the age range was selected until 20 boys and 20 girls in each institution had been identified. The mean age of the children in both groups was 11 years (range=9 years, 4 months to 12 years, 1 month).

All of the orphans had received protein supplements throughout the war, but fresh vegetables and fruit were always in short supply. Health examinations 5 years after the end of the war nevertheless indicated that the children were at the expected height and weight for their age, and there was no clinical evidence of any residual undernutrition or vitamin deficiencies.

All of the procedures and aims of the study were first discussed with members of the Ministry of Labour and Human Welfare, who supported the study but indicated that informed consent was an alien concept in Eritrean culture. The procedures were also discussed with the directors of the two institutions, and all of the potential participants were informed that participation was voluntary, and they could stop whenever they wanted.

Measures

The patterns of staff interaction, styles of child care management, and overall principles of governance in each institution were evaluated by a series of questionnaires that were designed for the special circumstances in the different social environments in Eritrea. They included the following.

Staff organization questionnaire

The director and several child care workers at each institution were asked to complete the questionnaire administered by trained research assistants, after the child care workers had been assured that their answers would be kept confidential. Each of the 13 questions could be answered in one of three mutually exclusive ways. A high score on this questionnaire (out of a possible score of 39) implied that the director made most of the decisions affecting the children by himself, without consulting the staff, and that explicit rules and exact activity schedules were an important aspect of the social organization. A low score (lowest possible score=13) implied that decisions affecting the children were reached by group consensus after active staff discussion, so that the staff members could share their observations, and that the individuality of the children was respected.

Child management inventory

The supervising child care worker at each institution completed 18 questions about the daily routines and rules that governed the everyday lives of the children. For example, they were asked about the interaction between staff members and children during mealtimes, whether the child care workers addressed the children by name, and whether the children had an opportunity to choose their own activities during free periods, were allowed to decorate their rooms, and were assigned a space for keeping their personal possessions. Each of the 18 questions could be answered in one of three mutually exclusive ways. Low scores (lowest possible score=18) indicated that children were allowed within reasonable limits to decide how they would spend their free time and holidays, whether or not to participate in group activities, and the like. High scores (out of a possible 54) implied that nearly all daily activities, including sleep/waking schedules on weekends and participation in group activities, were regulated by strict rules.

The following measures were used to assess the emotional state and cognitive development of the children.

Behavioral Symptom Questionnaire

This measure, which had been used in earlier studies (14), was expanded for use with older children. Questions were administered by trained Eritrean research assistants and completed by the child care worker who had spent the most time with the particular child. Questions focused on sleep and eating disturbances, deviant patterns of social interaction, affective disturbances, conduct disorders, and the like.

Projective picture

Each child was presented with an ambiguous drawing of an Eritrean woman in traditional dress bending over a young boy who was kneeling on the ground (figure 1). Since projective tests had not been used systematically in Eritrea, this was an exploratory effort. The scene had been copied from a photograph taken in the base camps, and the landscape closely resembled the environment of the camps. The children were asked to tell a story about the picture: what they saw, what they thought had led up to the situation, what would happen later, and what feelings and memories the picture evoked in them. The narratives were tape recorded, transcribed, and then translated from Tigrinia (the major language of Eritrea) into English for systematic coding of emotional content. Bilingual Eritreans who reviewed the narratives considered the translations to be accurate, although some subtle meanings were lost in translation.

Cognitive measures

The formal tests had all been standardized for English-speaking populations, and for obvious reasons none had been standardized for Eritrean or other East African populations. Because culturally inappropriate items had to be deleted or replaced, only the raw scores were used, and summary scores were used only for internal comparisons. These measures included 1) five subtests of the Kaufmann Assessment Battery for Children (15) that were thought to be most nearly culture-fair by Eritrean investigators: the hand, gesture, number recall, triangle, and word order subtests; 2) the Raven Progressive Matrices (Standard Series) (16); 3) relevant items from the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (17); the short form of the Token Test (18); and the children’s version of a naming confrontation test (19).

Statistical Evaluations

A preliminary display of raw data indicated that the test scores and frequency of behavioral symptoms were not normally distributed. The main and interaction effects by groups were therefore tested after the behavioral symptoms and performance scores on cognitive tests had been rank ordered by the RANK procedure of the SAS Procedures Guide (20). Ranks were entered as dependent measures in a general linear analysis of variance (ANOVA) model (20). Where appropriate, other nonparametric procedures (21) were also used. Only statistically significant main and interaction effects are reported in any detail.

RESULTS

The Institutions

Staff organization questionnaire

The director of orphanage A (total score=31) considered it his responsibility to make all decisions affecting the children, and he rarely consulted the staff on these issues. He believed that in order to give orphans a greater sense of security and predictability of daily schedules, it was important to organize the institution so that it would emulate the authoritative patterns of the traditional Eritrean family structure. By contrast, the director of orphanage B (total score=18) had modeled the institution after principles of governance developed at the Solomuna Orphanage during the war (14). Staff members participated actively in most decisions affecting the children and had created a social climate that respected the individuality of the children and encouraged their sense of autonomy. The child care workers at the two institutions answered most of the questions in the same way as the directors: those at orphanage A gave theirinstitution a mean total score of 29 (range=24–32); those at orphanage B gave their institution a mean total score of 17 (range=16–20).

Child management inventory

The senior child care worker at orphanage A (total score=44) reported that the institution was run by explicit rules and well-defined schedules. The staff supervised the children at mealtimes but did not eat with the children. The youngest children all slept together in one dormitory with one child care worker, but the staff rotated night duty on a daily basis. The children had few opportunities to express their personal preferences, and private possessions were discouraged. By contrast, the senior child care worker at orphanage B (total score=27) reported that several staff members always ate with the children, and that one adult always slept in the dormitories with the children. Within reasonable limits for age, the children could allocate their free time as they wanted, and each child was given a small locker for personal belongings.

The Children

Behavioral symptoms

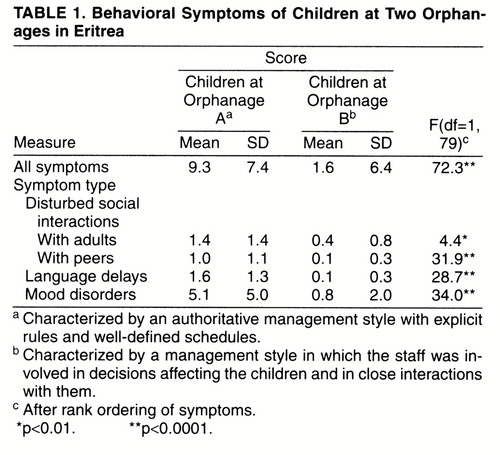

The overall frequency of behavioral symptoms as well as of symptom types differed significantly between the children in the two institutions. An ANOVA, with institution, sex, and age as between-subject variables and the rank order of behavioral symptoms as the dependent measure, indicated that there were main effects by institution but no main or interaction effects by sex or age (table 1). Children in orphanage A exhibited more symptoms altogether than those living in orphanage B. The most common symptoms in both groups, and the types of symptoms that accounted for most of the group differences, were mood disturbances, language delays, and disturbed social interactions with peers.

The child care workers at orphanage A volunteered the information that there were also marked differences between the personalities of orphans who had been relocated from the base camps after the war and those who spent the war years in orphanage A. Depending on their personal biases, they described the children from the war zones as either too aggressive and disrespectful of authority or as self-confident and outgoing, and the children who had grown up in orphanage A as either obedient and respectful or as too passive and dependent. The child care workers at orphanage B had not observed any such differences when they were specifically asked. It was difficult to assess the psychological implications of these informal observations without more systematic information, but the observations raised the possibility that during the war, the children in the different orphanages had assimilated qualitatively different values regarding obedience, personal autonomy, and appropriate social conduct, and that those children who were relocated from the base camps were more often in conflict with the staff that expected conformity (orphanage A) than in a residential setting that encouraged personal autonomy.

Projective picture

Children in both residential settings spontaneously commented on the emotional attitude of the woman and boy, and nearly all of their comments fell into one of two major categories. Whether or not they had come from the base camps after the war, most children in orphanage B perceived the woman’s actions as punitive and the boy as feeling guilty. By contrast, most children in orphanage A perceived the woman as trying to comfort the boy and the boy as needing comfort (χ2=29.1, df=1, p<0.001). However, it was difficult to interpret the psychological significance of these counterintuitive results without additional information about the children’s emotional state. The findings do, however, support the hypothesis that the emotional state of the children in the two institutions differed substantially, that the differences went beyond frequency of symptoms, and that they were apparently a function of the institution rather than of the children’s earlier experiences during the war.

Most of the orphans who had come from the war zones recognized the geographic location of the picture and spontaneously reminisced about their experiences during the war. Although they mentioned the dangers and physical hardships in the base camps, they remembered their life in the orphanage as a distinctly positive experience, since they had been respected as individuals and had gained a sense of self-confidence because their teachers encouraged them to search out new experiences. These unsolicited comments are consistent with the notion that the quality of child care and the emotional ambience of the residential setting played an important role in the psychological rehabilitation of the war orphans.

Cognitive performance

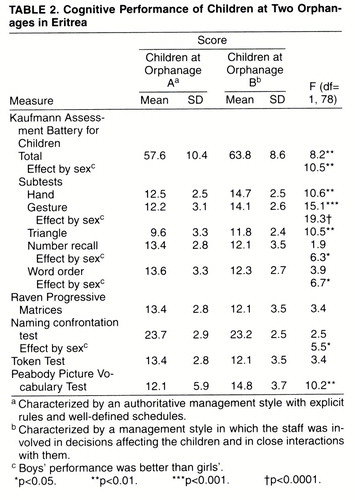

There were also significant differences between the two groups in level of performance on the formal cognitive measures. The ANOVAs with group and sex as classifying variables and rank scores on test performance as dependent measures indicated that the children in orphanage B performed on the total Kaufmann Assessment Battery for Children, as well as the individual hand, gesture, and triangle subtests, and on the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test at a more advanced level than the children in orphanage A (table 2). In addition, there were main effects by sex for the combined subtests of the Kaufmann Assessment Battery for Children and the individual gesture, number recall, and word order subtests and for the naming confrontation test; in each case boys performed at a more advanced level than girls. There were no main effects by group for the number recall and word order subtests, the Raven matrices, the naming confrontation test, or the Token Test, and there were no group-by-sex interactions.

While performance on the Kaufmann Assessment Battery for Children is usually correlated significantly with performance on the Raven matrices among children from Western cultures (15), the two sets of measures were not correlated among the Eritrean children. The reasons for this apparent cross-cultural difference were not clarified by the findings, but in informal exploratory observations, the Eritrean research assistants also seemed to have inordinate difficulty solving the Raven matrices.

Effects of parental status

As indicated, some children at each orphanage had lost both parents, while others had a surviving parent who sometimes came to visit but could not care for them at home. A nonparametric Mann-Whitney U statistic for independent samples (21) indicated that the loss of one or both parents was not associated with frequency of behavioral symptoms or level of cognitive performance.

DISCUSSION

The combined findings are consistent with the conclusion that styles of child management and patterns of staff interaction were significantly correlated with the emotional state and cognitive performance of orphans in the two institutions. Further, they suggest that the model of child care exemplified in orphanage B was more effective in meeting the emotional needs of war orphans than the style of child care management exemplified in orphanage A, which emphasized an authoritative structure (22). This conclusion is consistent with the somewhat idealized recollections of orphans from the base camps, which suggests that a residential setting that encouraged close emotional ties between staff and children may have served as an effective psychological buffer against the adverse effects of chronic exposure to the terrors of combat and the loss of both parents (23).

Although the loss of one or both parents during early childhood can have serious long-term psychological consequences, it apparently is not the traumatic event as such but the disruptions and chronic stresses surrounding the traumatic event that are responsible for adverse long-term outcomes, whereas the continuity of warm personal relationships with an adult or a coherent community of adults can often ameliorate such adverse effects (23-26). Moreover, one of the few studies to examine the long-term outcome of growing up in an orphanage suggests that adult orphans make remarkably good long-term life adaptations (27).

Specifically, the findings in this study serve as guidelines about how the remaining orphanages in Eritrea might be restructured to meet the needs of war orphans most effectively. At a more general level, the findings may also be useful for social service agencies in other Third World countries, which must face the daunting task of providing decent care for large numbers of homeless orphans, although the specific remedies devised in Eritrea must be modified in keeping with the historical and cultural requirements of other societies.

The generalizations to be drawn from these findings are limited by a number of methodological shortcomings. 1) The unstable social conditions during the war and the immediate postwar period were not the optimal setting for carrying out any rigorously controlled comparison studies. 2) The behavioral symptom questionnaires and psychological tests had not been standardized on any East African population. This may account in part for the finding that the Eritrean orphans’ scores on the Kaufmann Assessment Battery for Children and on the Raven matrices were not correlated, whereas these measures are usually correlated among children from Western cultures. However, focused cross-cultural comparisons are required for examining whether these discrepancies, as well as the sex differences in cognitive performance, reflect cross-cultural differences in cognitive performance and gender roles. 3) Very little was known about the social experiences of these children in their own families before they were institutionalized. Yet differences in social experience during early childhood may have contributed in important ways to individual differences in mental health among the Solomuna orphans (28)) The child care workers may have been biased in their description of the institutions and the children, either through a sense of loyalty to their institutions or through major disagreements with the director’s style of child management.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite these limitations, the findings challenge the categorical conclusion that orphanages are necessarily the breeding grounds of psychopathology and must therefore be avoided at all costs. Instead, they justify the conclusion that in countries where adoption and foster care are culturally unacceptable and logistically unrealistic, it is possible to create humane social environments for large numbers of children that will foster their emotional well-being and cognitive development, even when material resources are very limited and child development experts are in short supply. The success of such efforts is greatly enhanced when the social environment is organized to guarantee close and stable personal relationships between staff members and children, distributed responsibilities for decisions affecting the children, and a style of child management that respects the individuality and autonomy of each child.

Received Aug. 28, 1997; revisions received March 3 and May 28, 1998; accepted June 29, 1998. From Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston; and Redd Barna, Asmara, Eritrea.. Address reprint requests to Dr. Wolff, Children’s Hospital, 300 Longwood Ave., Carnegie 2, Boston, MA 02115. Supported by grant 94-1378-94 from the William T. Grant Foundation.The work summarized here was the collective effort of many dedicated Eritreans, but the two authors take full responsibility for the content of the report.

|

|

1. Bowlby J: Maternal Care and Mental Health. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1951Google Scholar

2. Spitz R: The psychogenic diseases in infancy. Psychoanal Study Child 1951; 6:255–275Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Provence S, Lipton M: Infants in Institutions. New York, International Universities Press, 1962Google Scholar

4. Gibson K: Children in political violence. Soc Sci Med 1989; 28:659–667Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Jensen PS, Shaw J: Children as victims of war: current knowledge. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1993; 32:697–708Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Macksoud MS, Dyregrou A, Raundalen M: Traumatic war experiences and their effects on children, in International Handbook of Traumatic Stress Syndromes. Edited by Wilson JP, Raphael B. New York, Plenum, 1993, pp 625–633Google Scholar

7. Bledsoe C, Ewbank D, Isiugo-Abanihe: The effect of child fostering on feeding practices and access to health services in rural Sierra Leone. Soc Sci Med 1988; 27:627–637Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Isiugo-Abanihe U: Child fosterage in West Africa. Population and Developmental Res 1985; 11:53–73Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Tiffin S: In Whose Best Interest? Child Welfare Reform in the Progressive Era. Westport, Conn, Greenwood Press, 1982Google Scholar

10. Pateman R: Eritrea: Even the Stones Are Burning. Trenton, NJ, Red Sea Press, 1990Google Scholar

11. Department of Social Affairs: Proposals and Recommendations to Meet the Psychological Needs of Orphans in Eritrea. Asmara, Republic of Eritrea, 1991Google Scholar

12. Wolff PH: War and the children of Eritrea, in Report of the First Eritrean International Conference on Primary Health Care. Orrota, Eritrea, Eritrean Medical Association, 1986Google Scholar

13. Wolff PH, Dawit Y, Zere B: The Solomuna orphanage: a historical survey. Soc Sci Med 1995; 40:1133–1139Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Wolff PH, Tesfai B, Eyasso H, Aradom T: The orphans of Eritrea: a comparison study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1995; 36:633–644Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Kaufmann AS, Kaufmann NL: K-ABC: Kaufmann Assessment Battery for Children. Circle Pines, Minn, American Guidance Service, 1983Google Scholar

16. Raven JC: Standard Progressive Matrices: Sets A, B, C, D, and E. London, HK Lewis, 1958Google Scholar

17. Dunn LM: Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test. Circle Pines, Minn, American Guidance Service, 1959Google Scholar

18. McNeal MR, Prescott TE: Revised Token Test. Austin, Tex, Pro-Ed, 1978Google Scholar

19. Gardner MF: Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test, Revised. Novato, Calif, Academic Therapy Publications, 1990Google Scholar

20. SAS/STAT Procedures Guide, version 6. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, 1992, pp 343–358Google Scholar

21. Siegel S: Nonparametric Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1956Google Scholar

22. Steinberg L, Elmen JD, Mouritz NS: Authoritative parenting, psychosocial maturity and academic success among adolescents. Child Dev 1989; 60:1424–1436Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Freud A, Danns S: An experiment in group upbringing. Psychoanal Study Child 1951; 6:127–168Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Rutter M, Maughan B: Psychosocial adversities in childhood and adult psychopathology. J Personality Disorders 1997; 11:4–18Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Tizard B, Hodges J: The effect of early institutional rearing on the development of eight year old children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1978; 19:99–118Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. MacFarlane AH, Bellissimo A, Norman GR: Family structure, family functioning and adolescent well-being: the transcendent influence of parental style. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1995; 36:847–864Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Gribble A, Cowen EL, Wyman PA, Work WC, Wannon M, Raog A: Parent and child views of parent-child relationships, qualities and residual outcomes among urban children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1993; 34:507–519Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. McKenzie RB: Orphanage alumni: how they have done and how they evaluate their experience. Child and Youth Care 1997; 26:87–111Crossref, Google Scholar