Characteristics of Borderline Personality Disorder Associated With Suicidal Behavior

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined the relationship between characteristics of borderline personality disorder and suicidal behavior. The authors hypothesized that a specific feature of borderline personality disorder, impulsivity, and childhood trauma, a possible etiological factor in the development of impulsivity, would be associated with suicidal behavior. METHOD: Information on lifetime history of suicidal behavior was obtained from 214 inpatients diagnosed with borderline personality disorder by structured clinical interview. The authors examined the relationship between DSM-III-R criteria met and the following measures of suicidal behavior: presence or absence of a previous suicide attempt, number of previous attempts, and lethality and intent to die associated with the most lethal lifetime attempt. RESULTS: Impulsivity was the only characteristic of borderline personality disorder (excluding the self-destructive criterion) that was associated with a higher number of previous suicide attempts after control for lifetime diagnoses of depression and substance abuse. Global severity of pathology of borderline personality disorder was not associated with suicidal behavior. History of childhood abuse correlated significantly with number of lifetime suicide attempts. CONCLUSIONS: The trait of impulsivity is associated with number of lifetime suicide attempts and may therefore be a putative risk factor for a future suicide attempt. If so, impulsivity is a potential target therapeutically for prevention of future suicide attempts. The association between childhood abuse and number of lifetime suicide attempts is consistent with the hypothesis that childhood abuse is an etiological factor in the development of self-destructive behaviors. (Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1715–1719)

Adiagnosis of borderline personality disorder is a distinct risk factor for suicidal behavior. Rates of suicide among patients with borderline personality disorder range from 3% to 9.5% (1–5), and Gunderson (6) found that 75% of an inpatient sample with borderline personality disorder had made at least one previous suicide gesture. Earlier studies (4, 5, 7–13) identified correlates of suicidal behavior in subjects with borderline personality disorder that were not related to personality traits, such as age, educational level (7, 9), more frequent childhood losses (12), lack of treatment contact before hospitalizations (12), and comorbid axis I diagnoses of major depression, substance abuse, and eating disorders (4, 10). The number of previous suicide attempts has been found to be the strongest predictor of suicide and future suicidal behavior in all psychiatric populations including subjects with borderline personality disorder (9, 10, 14, 15).

These studies (4, 5, 7) also suggest that the presence of axis I affective and substance abuse diagnoses are insufficient to explain suicidal behavior among patients with borderline personality disorder. Conversely, we have previously proposed that the presence of major depression may be necessary but insufficient to explain suicidal behavior in individuals who have major depression without borderline personality disorder (16). Comorbid borderline personality disorder and major depression are associated with more suicidal behavior than major depression without comorbid borderline personality disorder, despite comparable severity of depression (16). We have proposed a diathesis-stress model for suicidal behavior in which an episode of major depression is the stressor and borderline personality disorder is part of the diathesis. Personality characteristics such as impulsivity and aggression, often characteristic of borderline personality disorder, have been found to correlate with suicide risk in other psychiatric populations (14). Therefore, we propose that these traits also determine risk for suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder.

The high prevalence of a history of childhood abuse among populations with borderline personality disorder has stimulated investigation of the developmental consequences of childhood abuse and its role in the etiology of borderline personality disorder (17–20). The association of childhood abuse history with self-destructive behaviors including suicidal behavior may be mediated by a causal relationship between childhood abuse experiences and the development of particular personality traits, such as impulsivity and anger dysregulation, that might then be associated with self-destructive behaviors in adulthood. Alternatively, children who already have excessive impulsivity and aggressive traits may be at greater risk for abuse. Nevertheless, presence or absence of a childhood abuse history should be determined when considering the relationship between borderline personality characteristics and suicidal behavior.

The present study was undertaken to specifically examine the relationship of individual characteristics of borderline personality disorder and overall severity of borderline personality disorder to childhood abuse history and the relationship of both to the following measures of suicidal behavior: history of a previous suicide attempt, number of previous attempts, and intent and lethality of the most lethal lifetime attempt. We hypothesized that suicidal behavior would be predicted by specific borderline personality characteristics, such as impulsivity, more so than by global severity of borderline personality disorder. We also hypothesized that a history of childhood abuse would be associated with suicidal behaviors and the associated traits of impulsivity and anger dysregulation.

METHOD

Subjects

A total of 214 inpatients were identified from two university sites independently conducting research studies into borderline personality disorder and substance abuse (21) and borderline personality disorder, depression, and suicidal behavior (16). More detailed elaboration of the method of each study has been presented elsewhere (22, 23). Pooling data from these two sites generated a sufficiently large group of inpatients with borderline personality disorder to investigate correlates of suicidal behavior and was possible because the patients at the two sites were comparable with regard to variables found to correlate with suicidal behavior. The study group consisted of 157 inpatients at the Payne Whitney Clinic of the New York Hospital-Cornell Medical College in New York City and 57 inpatients at Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic in Pittsburgh.

Procedure

Recruitment procedures and measures at the two sites were similar but not identical. The New York City group gave written informed consent and met at least five of the eight DSM-III-R criteria for borderline personality disorder. The charts of all newly admitted patients between 18 and 60 years of age who did not have a clinician's diagnosis of organic brain syndrome, major depression with psychotic features, or schizophrenia were carefully screened within 3 days of admission. The 57 patients in Pittsburgh represent a subgroup of a larger group of inpatients between 18 and 80 years of age who gave written informed consent and were screened at admission for current major depressive episode and borderline personality disorder. Exclusion criteria were major medical illness, organic mental disorders, and IQ under 80.

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (24) was used to determine axis I diagnoses at both sites. At the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic in Pittsburgh, diagnoses were assessed through the administration of structured clinical interviews and then established at consensus diagnosis conferences. The assessment of axis II personality disorders represents the main difference in measures between the two sites; the pilot version of the Personality Disorder Examination (25) was used at Pittsburgh, while the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (26) was used in New York. Cross-site reliability studies of personality disorder assessment instruments report that these two structured clinical interview measures have similar reliabilities at yielding diagnoses according to DSM-III-R criteria (27). Skodol et al. (28) found modest agreement of these two measures on categorical diagnoses but better agreement on dimensional assessments, which are the focus of this study. Nevertheless, since inclusion in the study was based on categorical diagnosis of borderline personality disorder, we have controlled for possible differences in measurement of borderline personality disorder by including site as a covariate in the statistical analysis.

The only other difference in data collection pertains to the measurement of abuse history. In the New York group, the Sexual Experiences Questionnaire (29), a self-report form, was administered to a subgroup of 60 subjects, asking them to report the severity, perpetrator, and age at onset of sexual or physical abuse or both experienced before the age of 16 and perpetrated by an adult at least 5 years older. In the Pittsburgh group, abuse history was determined by clinical interview and was documented as absent or as present if subjects reported having experienced physical or sexual abuse or both before the age of 15.

All other measurement instruments were identical across sites. Severity of current state of depressive symptoms was measured with the Hamilton Depression Scale (30) and the Beck Hopelessness Inventory (31), a self-report measure, administered within the first week of hospital admission. A detailed lifetime history of suicidal behavior including number of previous attempts was obtained at both sites, and the level of intent for the most lethal attempt was measured by Beck's Suicide Intent Scale (32). Beck's Suicide Lethality Scale (33) scored the degree of medical damage inflicted during the most recent and most lethal suicide attempts.

Analyses

Regression analyses were performed; the continuous suicidal behavior variables (number of previous attempts, lethality, and intent associated with most lethal attempt) were used as criterion variables, and borderline personality disorder criteria were used as predictor variables to test our hypotheses about the personality characteristics that were associated with the various types of suicide indices. The variable concerning number of previous attempts was transformed by taking the square root to normalize the distribution, in order to use parametric analyses.

Univariate analyses were performed to compare the two groups regarding demographic and study variables. No differences were observed in demographic variables between sites. On study variables, there were no differences in hopelessness scores or in number of borderline personality disorder criteria met. The lethality of the most lethal suicide attempt was significantly higher among subjects at the Pittsburgh site (mean Pittsburgh lethality score=3.6, SD=1.7; mean New York score=2.6, SD=1.8) (t=2.29, df=86, p=0.03), and there was a higher proportion of subjects with a history of suicide attempts in the Pittsburgh group (83% versus 63%) (χ2=4.2, df=1, p<0.05). There were no differences between sites in the proportion of subjects meeting criteria for current or lifetime major depressive episode; in age, sex, race, or socioeconomic status of those with and without histories of a suicide attempt; or between those who met five, six, and seven borderline personality disorder criteria.

Student t tests compared mean suicide and depression measures between abused and nonabused groups and between those who met criteria for each borderline personality disorder criterion and those who did not. Chi-square analyses tested relationships between abuse history and 1) each borderline personality disorder criterion and 2) attempter status, and 3) the relationship between borderline personality disorder criteria and attempter status. Subjects were divided into three groups according to the number of borderline personality disorder criteria they met (five, six, or seven), excluding the criterion related to self-destructive behavior. Univariate analyses of variance tested differences in suicide measures among these three groups.

In order to identify the borderline personality characteristics that accompany suicidal behavior, we removed the DSM-III-R criterion that involves suicidal behavior from all categorical and dimensional measures of borderline personality disorder. All analyses were performed on subjects who met five criteria for borderline personality disorder, excluding the criterion regarding self-destructive behavior (N=156; 127 from New York and 29 from Pittsburgh). Of these 156 subjects, 104 had made at least one suicide attempt in the past, and 52 had never attempted suicide. Thus, the analyses involving suicidal behavior variables such as number of previous attempts, lethality, and intent were performed on the group of 104 subjects who had a history of suicide attempts.

A post hoc regression analysis was performed on the subset of the group for which childhood abuse history was obtained in order to add abuse history to the model of variables hypothesized to predict number of previous suicide attempts.

RESULTS

No differences were found among subjects who met five, six, or seven borderline personality disorder criteria in terms of the following suicide variables: 1) number of attempts (F=0.21, df=2,153, p=0.81), 2) lethality (F=0.35, df=2,87, p=0.71), and 3) intent (F=0.51, df=2,85, p=0.60). The mean number of borderline personality disorder criteria met did not distinguish between those with a history of suicide attempts (mean=5.8, SD=0.8) and those without (mean=5.9, SD=0.8) (t=–0.36, df=154, p=0.73).

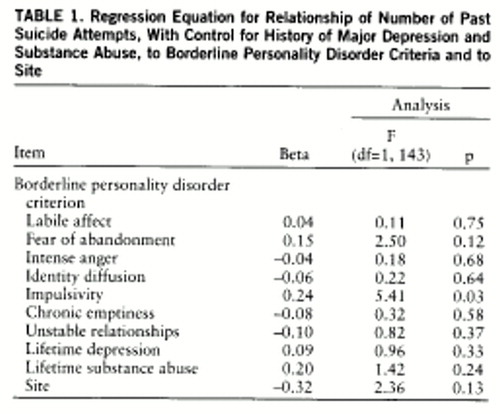

The impulsivity criterion was the one borderline personality disorder characteristic significantly correlated with number of previous suicide attempts (table 1). In an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) that controlled for lifetime major depression and substance abuse diagnoses, patients with borderline personality disorder who met the impulsivity criterion had more past suicide attempts than those who did not meet the impulsivity criterion (mean=2.34, SD=2.57, versus mean=1.31, SD=1.67) (F=3.62, df=1,150, p=0.03). None of the borderline personality disorder criteria was significantly correlated with attempter status or with the lethality or intent of the most lethal lifetime attempt.

Among the subgroup (N=74) whose abuse history was obtained, a significant association was found between the presence of an abuse history and number of previous suicide attempts when lifetime prevalence of a major depressive episode and lifetime or current substance abuse were controlled in an ANCOVA (F=5.10, df=1,72, p=0.03). Mean number of previous attempts was greater for those who reported a history of abuse than for those with no history of abuse (mean=3.06, SD=3.03, versus mean=1.85, SD=1.73) (t=–2.02, df=72, p=0.05).

No association was found between the total number of criteria met for borderline personality disorder and abuse history (t=–0.86, df=72, p=0.40), and there was no association between individual criteria for borderline personality disorder and abuse history.

In a post hoc regression analysis that included abuse history and the impulsivity criterion as predictor variables and controlled for lifetime major depression and substance abuse diagnoses, neither abuse history nor impulsivity was significantly correlated with number of previous suicide attempts.

Among the group of 156 subjects who met criteria for borderline personality disorder, excluding the self-destructive criterion, there were no statistically significant relationships between borderline personality disorder criteria.

DISCUSSION

This is the largest study reported to date of suicidal behavior in patients with borderline personality disorder diagnosed by DSM-III-R structured interview and the only study we are aware of that investigates the relationship between individual characteristics of borderline personality disorder and various measures of suicidal behavior. We found that the single borderline personality disorder trait of impulsivity, rather than global severity of borderline personality disorder pathology, is associated with suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder. The impulsivity criterion of borderline personality disorder, even after control for lifetime prevalence of major depression and substance abuse, was associated with more previous suicide attempts among inpatients with borderline personality disorder.

This finding suggests that the presence or absence of the impulsivity trait accompanies differences in the propensity to attempt suicide. Corbitt et al. (22) found that a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder, as well as the total number of comorbid cluster B personality features in depressed inpatients, but not severity of depression, correlated with number and lethality of previous suicide attempts. That study did not evaluate the relationship of suicidal behavior to individual borderline personality disorder traits. Similarly, patients with comorbid borderline personality disorder and antisocial personality characteristics are more likely to have attempted suicide (7), or are at higher risk for a future attempt (10), than those without such comorbidity. Shearer et al. (10) found that the presence of histrionic personality traits was negatively correlated with a statistically derived measure of risk of suicide. The alternative possibility, that global severity of borderline personality disorder pathology rather than any one characteristic is more predictive of suicidal behavior in this population, was not supported by our findings.

To meet the impulsivity criterion, subjects had to endorse impulsive behavior in at least two areas of life, such as binge eating and shopping, gambling, substance use, or reckless driving, but we excluded directly self-destructive behaviors such as suicide attempts or parasuicidal self-injury. Since the number of previous suicide attempts is consistently identified as predictive of a future attempt (7, 9, 10, 12), the presence of impulsivity in at least two other areas of a borderline patient's life suggests that all three domains are consequences of greater impulsivity.

A history of childhood sexual or physical abuse or both was associated with a higher number of previous suicide attempts. This finding is consistent with previous studies that have reported a relationship between childhood abuse history and suicide attempter status (34, 35) and with self-damaging behaviors such as self-mutilation (29, 36), and furthers the notion that body-inflicted childhood trauma is associated with bodily self-harm in adulthood. More research is needed to specify the type, duration, and age at onset of abuse that are associated with future suicidal behavior.

However, despite our findings that both the trait of impulsivity and childhood abuse history were associated with a higher number of previous suicide attempts, our hypothesis that these relationships might be mediated by an association between trait impulsivity and childhood abuse history was not confirmed by the current study. Thus, although both impulsivity and abuse history appear to be associated with a higher number of previous suicide attempts, the relationship, if any, between abuse history and impulsivity remains to be determined.

It is clear that suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder is a multidetermined phenomenon. However, our findings suggest that reduction of impulsivity may be one promising approach for prevention of suicide attempts in this population. An example of such a psychotherapeutic approach is Linehan's dialectical behavioral therapy (37), which applies behavioral techniques and teaches skills aimed at control of impulsive behaviors.

An additional therapeutic approach is to reduce impulsivity through medication intervention. A relationship has been reported between reduced serotonergic functioning and increased impulsivity in suicidal patients (38–40). The serotonin neurotransmitter system has been found to mediate symptoms and traits of impulsive personality disorders (41), and reduced serotonergic functioning (as measured by CSF 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid) has been found to correlate with risk of suicide and aggressive behavioral traits in psychiatric populations (42) and in criminals with personality disorders (38). Thus, future studies should examine the possibility of reducing impulsivity by increasing serotonergic functioning through use of medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. If our hypothesis that psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy to reduce impulsivity will reduce suicidal behavior proves correct, then monitoring impulsivity will be a guide to therapeutic response.

This study found a relationship between impulsivity in borderline personality disorder and the number of previous suicide attempts. Other features of borderline personality disorder did not correlate with suicidal behavior. Future studies are needed to further clarify the role of impulsivity in mediating suicide risk in other psychiatric conditions and the effect of reduced impulsivity on risk of future suicidal behavior.

|

Presented at the 149th annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, New York, May 4–9, 1996. Received Feb. 3, 1997; revision received June 16, 1997; accepted July 17, 1997. From the Department of Neuroscience, New York State Psychiatric Institute, and Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University, New York; and New York Hospital-Cornell University Medical College, Westchester Division, White Plains, N.Y. Address reprint requests to Dr. Brodsky, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Box 28, 722 West 168th St., New York, NY 10032. Supported in part by NIMH grant MH-48514 and in part by a fund established in the New York community trust by DeWitt-Wallace (Dr. Dulit). Donna Abbondanza and Thomas Kelly provided assistance in clinical assessments.

1. McGlashan TH: The longitudinal profile of borderline personality disorder: contributions from the Chestnut Lodge follow-up, in Handbook of Borderline Disorders. Edited by Silver D, Rosenbluth M. Madison, Conn, International Universities Press, 1992, pp 53–88Google Scholar

2. Akiskal HS, Chen SE, Davis GC: Borderline: an adjective in search of a noun. J Clin Psychiatry 1985; 46:41–48Medline, Google Scholar

3. Pope HG Jr, Jonas JM, Hudson JI: The validity of DSM-III borderline personality disorder: a phenomenologic, family history, treatment response, and long-term follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983; 40:23–30Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Stone MH, Stone DK, Hurt SW: Natural history of borderline patients treated by intensive hospitalization. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1987; 10:185–206Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Fyer MR, Frances AJ, Sullivan T, Hurt SW, Clarkin J: Suicide attempts in patients with borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:737–739Link, Google Scholar

6. Gunderson JG: Borderline Personality Disorder. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1984Google Scholar

7. Soloff PH, Lis JA, Kelly T, Cornelius J, Ulrich R: Risk factors for suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1316–1323Google Scholar

8. Paris J: Completed suicide in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatr Annals 1990; 20:19–21Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Paris J, Nowlis D, Brown R: Predictors of suicide in borderline personality disorder. Can J Psychiatry 1989; 34:8–9Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Shearer SL, Peters CP, Quaytman MS, Wadman BE: Intent and lethality of suicide attempts among female borderline inpatients. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:1424–1427Google Scholar

11. Mehlum L, Friis S, Vaglum P, Karterud S: The longitudinal pattern of suicidal behaviour in borderline personality disorder: a prospective follow-up study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994; 90:124–130Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Kjelsberg E, Eikeseth PH, Dahl AA: Suicide in borderline patients—predictive factors. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1991; 84:283–287Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Stone MH: The Fate of Borderline Patients: Successful Outcome and Psychiatric Practice. New York, Guilford Press, 1990Google Scholar

14. Apter A, Kotler M, Sevy S, Plutchik R, Brown S-L, Foster H, Hillbrand M, Korn ML, van Praag HM: Correlates of risk of suicide in violent and nonviolent psychiatric patients. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:883–887Link, Google Scholar

15. Runeson B, Beskow J: Borderline personality disorder in young Swedish suicides. J Nerv Ment Dis 1991; 179:153–156Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Malone KM, Haas GL, Sweeney JA, Mann JJ: Major depression and the risk of attempted suicide. J Affect Disord 1995; 34:173–185Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Ogata SN, Silk KR, Goodrich S, Lohr NE, Westen D, Hill EM: Childhood sexual and physical abuse in adult patients with borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:1008–1013Google Scholar

18. Herman JL, Perry JC, van der Kolk BA: Childhood trauma in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146:490–495Link, Google Scholar

19. Carmen EH, Reiker PP: A psychosocial model of the victim to patient process: implications for treatment. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1989; 12:431–444Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Cole P, Putnam FW: Effect of incest on self and social functioning: a developmental psychopathology perspective. J Consult Clin Psychol 1992; 60:174–184Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Dulit RA, Fyer MR, Haas GL, Sullivan T, Frances AJ: Substance use in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:1002–1007Google Scholar

22. Corbitt EM, Malone KM, Haas GL, Mann JJ: Suicidal behavior in patients with major depression and comorbid personality disorders. J Affect Disord 1996; 39:61–72Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Dulit RA, Fyer MR, Leon AC, Brodsky BS, Frances AJ: Clinical correlates of self-mutilation in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1305–1311Google Scholar

24. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: User's Guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

25. Loranger AW, Lenzenweger MF, Gartner AF, Lehmann-Susman V, Herzig J, Zammit GK: Trait-state artifacts and the diagnosis of personality disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:720–728Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (SCID-II). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

27. Zimmerman M: Diagnosing personality disorders: a review of issues and research methods. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:225–245Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Skodol AE, Oldham JM, Rosnick L, Kellman, HD, Hyler SE: Diagnosis of DSM-III-R personality disorders: a comparison of two structured interviews. Int J Methods in Psychiatr Res 1991; 1:13–26Google Scholar

29. Wagner AW, Linehan MM: Relationship between childhood sexual abuse and topography of parasuicide among women with borderline personality disorder. J Personality Disorders 1994; 8:1–9Crossref, Google Scholar

30. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Beck AT, Weissman A, Lester D, Trexler L: The measurement of pessimism: the Hopelessness Scale. J Consult Clin Psychol 1974; 42:861–865Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Beck AT, Schuyler D, Herman J: Development of suicidal intent scales, in The Prediction of Suicide. Edited by Beck AT, Resnick HL, Lettieri DJ. Bowie, Md, Charles Press, 1974, pp 45–56Google Scholar

33. Beck AT, Beck R, Kovacs M: Classification of suicidal behaviors: I. Quantifying intent and medical lethality. Am J Psychiatry 1975; 132:285–287Link, Google Scholar

34. Farber EW, Herbert SE, Reviere SL: Childhood abuse and suicidality in obstetrics patients in a hospital based urban prenatal clinic. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1996; 18:56–60Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Briere J, Runtz M: Differential adult symptomatology associated with three types of childhood abuse histories. Child Abuse Negl 1990; 14:357–364Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. van der Kolk BA, Perry JC, Herman JL: Childhood origins of self-destructive behavior. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1665–1671Google Scholar

37. Linehan MM: Cognitive Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, Guilford Press, 1993Google Scholar

38. Roy A, Linnoila M: Suicidal behavior, impulsiveness and serotonin. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1988; 78:529–535Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Coccaro EF: Central serotonin and impulsive aggression. Br J Psychiatry 1989; 155(suppl):52–62Google Scholar

40. Linnoila M, Virkkunen M. Biologic correlates of suicidal risk and aggressive behavioral traits. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1992; 12(April suppl):19S–20SGoogle Scholar

41. Stein D, Hollander E, Leibowitz MR: Neurobiology of impulsivity and impulse control disorders. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1993; 5:9–17Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Mann JJ, Malone KM: Cerebrospinal fluid amines and higher-lethality suicide attempts in depressed inpatients. Biol Psychiatry 1997; 41:162–167Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar