Recovery From Major Depression in Older Adults Receiving Augmentation of Antidepressant Pharmacotherapy

Abstract

Objective: Few data are available concerning the utility of augmentation in late-life depression treatment. The authors examined likelihood, speed, and predictors of recovery in older adults receiving augmentation pharmacotherapy after inadequate response to standardized treatment with paroxetine plus interpersonal psychotherapy. Method: Depression levels were monitored during open treatment in 195 adults age 70 or older. Patients were grouped by whether they required augmentation (bupropion, nortriptyline, or lithium) and compared on likelihood, time, and predictors of recovery. Results: Augmentation was required for 105 patients (53.8%) because of inadequate treatment response (N=77) or response followed by relapse (N=28). Of these patients, 69 received augmentation and 36 did not (primarily because of consent withdrawal or comorbid medical conditions). Patients receiving augmentation showed lower recovery rates than patients never requiring augmentation: recovery occurred in 50.0% of patients receiving it because of inadequate response, 66.7% of those receiving it after early relapse, and 86.7% of patients never requiring augmentation. Patients receiving augmentation because of inadequate response recovered more slowly, with modestly more side effects than other patients. Greater medical burden and anxiety predicted slower recovery. Conclusions: Despite a lower likelihood of recovery in elderly people receiving augmentation, the recovery by over one-half of such patients suggests the value of augmentation for those able to tolerate it. Need for augmentation presages slower recovery in patients showing initial inadequate response; those requiring it after early relapse recovered more quickly. Strategies to further improve the likelihood and speed of recovery after initial treatment failure are needed.

When older adults with major depressive disorder are offered antidepressant pharmacotherapy at adequate doses, up to 84% of individuals either have inadequate responses or respond but relapse during the first 6–12 weeks of treatment (1) . Ultimately, 20% to 30% do not achieve full recovery (1 – 3) . These patients experience significant residual disability, reduced quality of life, and increased risk for all-cause mortality (4 , 5) . One strategy that may enhance antidepressant response and promote recovery is augmentation of an initial antidepressant with either a second antidepressant or another agent (e.g., lithium) (6 , 7) .

In young and middle-aged adults, a growing body of work suggests that augmentation can play an important role in optimizing antidepressant response, symptom relief, and recovery from major depression (6 – 8) . In contrast, little systematic work has examined progress toward recovery in older adults receiving augmentation, especially in the context of newer antidepressants, such as selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and dual-reuptake inhibitors. This may be due in part to a continuing hesitation in both clinical and research settings to consider implementing augmentation strategies in older adults, given their higher level of general medical burden and concerns over their inability to tolerate additional psychotropic medications (9) . Yet anecdotal accounts and small case series have shown favorable clinical outcomes with various strategies to augment initial SSRIs in older adults (10 – 12) . The few larger empirical investigations have been open trials or retrospective studies of patients initially treated with tricyclics (3 , 13 – 17) . These studies also suggest that augmentation with a variety of agents may facilitate recovery in older adults. However, with few exceptions (14) they did not implement augmentation according to a standardized protocol but instead relied on the treating clinician’s choice of either initial antidepressant or augmenting agent, timing of augmentation, target dose, and titration.

Earlier we reported on response to depression treatment in older adults receiving augmentation of an initial SSRI according to a standardized protocol (18) . This descriptive study focused on a subset of the patients described in the present report, and the results indicated that 60% of patients receiving paroxetine augmented by a second agent (sustained-release bupropion, nortriptyline, or lithium) achieved treatment response. However, we did not examine the likelihood of recovery from major depressive disorder in these patients or compare it to the likelihood for patients not requiring augmentation. Furthermore, neither our own nor others’ work has examined predictors of recovery speed once augmentation has begun, despite the potential value of such information for making clinical decisions about whether to continue with an augmentation strategy versus opting for other treatment approaches (e.g., switching to another antidepressant). Finally, given many older adults’ elevated medical burden and their personal preferences regarding treatment, not all patients can or will agree to augmentation (14) . Hence, any analysis of likelihood or predictors of recovery must be considered in the context of which older adults who need augmentation actually receive it. This information is essential for the ultimate interpretation of any data regarding the association of use of augmentation with treatment outcomes.

In the present study, we were able to examine these issues in a cohort of older adults who received a controlled treatment package for major depressive disorder and were followed closely during an extended observation period. These patients had enrolled in a trial of maintenance therapies for late-life depression (19) , which included standardized (open) treatment with paroxetine and interpersonal psychotherapy (20) , plus augmentation when specified by the protocol, before assignment to the maintenance conditions. The study’s open treatment phase provided us a unique opportunity to pursue three goals. First, we examined the proportion of older adults who required augmentation, and within that group, we sought to identify variables associated with who received it. Second, we compared the likelihood of recovery in individuals who received augmentation and in those who never required it. Third, we sought to determine what factors predicted speed of recovery from major depression after augmentation was begun. Potential predictors were identified on the basis of the larger literature on risk factors found empirically or observed anecdotally to be associated with slowed treatment response in late-life depression (1) . We hypothesized that they could affect temporal response to augmentation as well.

Method

Subjects

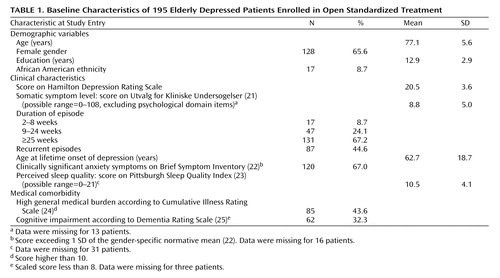

The study included 195 persons age 70 years or older ( Table 1 ). All participated in an investigation of maintenance therapies for major depressive disorder (19) ; the data described here were gathered during open treatment, before assignment to maintenance therapy. The subjects were required to meet the DSM-IV criteria for current nondelusional unipolar major depressive disorder, determined by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (26) . They were also required to score 15 or higher on the 17-item version of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) (27) , to score 17 or higher on the Mini-Mental State Examination (28) , and to have no evidence of substance abuse within the past 6 months.

Procedure

The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. After providing informed consent, patients were treated openly at our Late Life Mood Disorders Outpatient Treatment Clinic with both paroxetine and standardized interpersonal psychotherapy (20) . The dose of paroxetine was initially 10 mg/day and was titrated over 8 weeks to a maximum of 40 mg/day. Psychotherapy was weekly until patients achieved a clinical response (defined as a HAM-D score of 10 or less for 3 consecutive weeks) and biweekly for 16 weeks of continued treatment (regardless of whether or not patients required augmentation). Among patients achieving a clinical response, relapse was defined as a HAM-D score higher than 10 for 2 consecutive weeks and evidence that the criteria for major depression were again fully met on the SCID. The study’s open phase ended after the patients completed the 16 weeks of continuation treatment with HAM-D scores that remained 10 or below (full recovery) or if their scores during this period remained 11–14 (partial recovery).

“Augmentation” was defined as the addition of either a second antidepressant or another agent (6) . We used three agents—sustained-release bupropion, nortriptyline, and lithium carbonate—in keeping with expert consensus regarding the optimal medications for augmentation in pharmacologic treatment of late-life major depressive disorder (29) . A standardized protocol for selection of the augmenting agent, target dose, and titration was followed (18 , 29) . Thus, the treatment team reached initial consensus judgment on which of the augmenting agents should be employed for a given patient, on the basis of the patient’s medical status and history. In the absence of medical contraindications regarding any given augmenting agent, sustained-release bupropion was the first-line augmenting agent, followed by nortriptyline, and then lithium. Augmentation was offered if 1) a patient showed limited or no evidence of moving toward clinical response, according to the weekly HAM-D scores, or 2) the patient had achieved initial clinical response but then relapsed. The average time to the offer of augmentation was 12.9 weeks (SD=8.2). If, after a given augmenting agent was started and the dose was titrated, the patient showed no clinical response (as defined earlier), the next agent in the hierarchy was begun. The starting bupropion dose was 150 mg/day, which continued for 1 week and was increased to a maximum of 400 mg/day, according to tolerability and clinical response. The doses of nortriptyline and lithium were titrated as tolerated to maintain plasma levels of 80 to 120 ng/liter and 0.5 to 0.7 meq/liter, respectively.

Measures

Dependent measures

We considered two classes of outcomes: 1) whether patients required and received augmentation therapy and 2) whether patients recovered from the depressive episode, side effects by the end of the study, and speed of recovery.

Baseline predictors

Demographic, clinical, and medical comorbidity characteristics were collected before the inception of open therapy and were considered as possible predictors of augmentation outcomes.

The demographic characteristics included age, gender, and education. (Race was not examined because the proportion of ethnic minorities was too small for meaningful analysis; see Table 1 ). The clinical variables included HAM-D depression severity score (interrater reliability, intraclass r=0.95 in the present study) and somatic symptom severity, assessed by the Utvalg for Kliniske Undersogelser scale (21) , with the depressed mood and other psychological domain items removed (interrater reliability=0.87 for the present study). Current and lifetime major depressive disorder characteristics (current episode duration, whether the episode was the first lifetime episode, and the patient’s age at first lifetime episode) were ascertained from the SCID assessment. Anxiety symptoms were assessed with the self-reported Brief Symptom Inventory (22) anxiety subscale (internal consistency reliability, Cronbach’s alpha=0.84 for the present study), and the patients were categorized according to whether they showed a clinically significant anxiety level, defined as a score exceeding 1 SD of the gender-specific normative mean (22) . Perceived sleep quality was assessed with the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (23) (alpha=0.67 for this study).

Severity of overall chronic medical (nonpsychiatric) burden was assessed with the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for older adults (24) . The scale yields a total medical burden score across 13 organ systems. We dichotomized the scores to distinguish individuals with a relatively low total medical burden (score of 10 or less) versus higher burden. This cutpoint, which we used to define clinically significant burden, was based on literature showing that scores of 10 or less generally identify the healthiest older adults among individuals seeking medical care (i.e., individuals falling at least 1 SD below the normative mean) (24 , 30) . Severity of cognitive impairment was assessed with the Dementia Rating Scale (25) . The total scaled score (which adjusts for the patient’s age and education) was dichotomized to identify patients with clinically significant cognitive impairment, i.e., scaled scores less than 8 (31) .

Analyses

The proportions of patients requiring and receiving augmentation, and reasons for termination from the study without augmentation, were examined. Among patients requiring augmentation, those who received it were compared to those who did not on baseline demographic, clinical, and medical factors, by using chi-square tests for proportions and t tests for means. Likelihood of recovery, occurrence of medication side effects, and speed of recovery were compared in the patients receiving augmentation and those who did not require it. Chi-square tests for proportions, F tests for means, and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with log-rank tests comparing the survival functions were used for these comparisons. Cox proportional hazards models were fit in order to examine whether baseline demographic, clinical, and medical comorbidity variables predicted differences in time to recovery among patients who received augmentation.

Results

Who Needs and Accepts Augmentation?

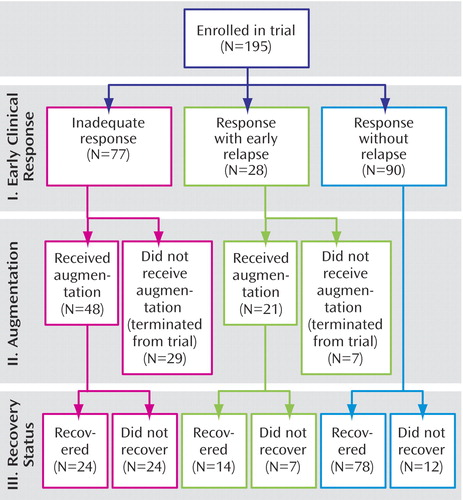

Figure 1 shows that of the 195 patients enrolled, 77 (39.5%) had little to no initial response to combined treatment with paroxetine and interpersonal psychotherapy, 28 (14.4%) showed an initial clinical response but relapsed, and the remaining 90 patients (46.2%) showed an initial response and never relapsed.

A total of 69 patients received augmentation: 48 (62.3%) of the 77 who showed inadequate treatment response and 21 (75.0%) of the 28 patients with early relapse ( Figure 1 ). The remaining 36 individuals (29 who showed inadequate treatment response and seven who relapsed) were eligible for augmentation but did not receive it. Among these, 15 withdrew consent for the study and 21 were removed from the study: three were judged to require mental health treatment other than that provided in the study (e.g., ECT), and 18 experienced incident symptoms or medical conditions or exacerbations of preexisting medical conditions that were judged by the treatment team to preclude study continuation (incident symptoms such as hyponatremia or rash, N=10; incident medical conditions such as cancer, N=3; worsening of preexisting medical condition such as progression to congestive heart failure, N=5).

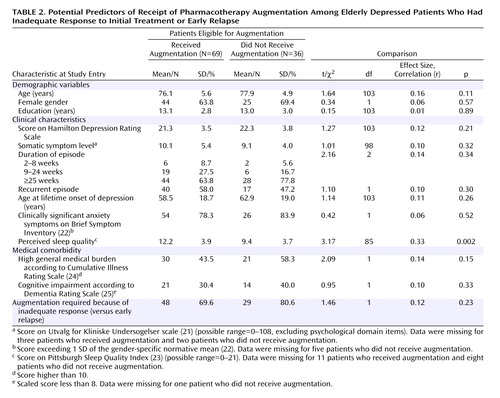

Among the patients eligible for augmentation, we compared all patients who received it (N=69) to those who did not (N=36) on baseline variables, as well as whether they had shown any initial response to treatment ( Table 2 ). Only one significant difference emerged: individuals who received augmentation had poorer perceived sleep quality at baseline. The size of this association was moderate. All remaining variables showed small and nonsignificant associations with receipt of augmentation.

Is Augmentation Related to Likelihood, Quality, and Speed of Recovery?

The bottom row of Figure 1 shows the numbers of patients who continued in the trial beyond the decision point regarding augmentation (if required) and who either recovered from depression or did not. Patients who received augmentation showed a lower likelihood of recovery than patients who did not require augmentation. Thus, 50.0% of the patients receiving augmentation because of inadequate treatment response ultimately recovered (24 of 48), as did 66.7% of those receiving augmentation after an early relapse (14 of 21). In contrast, 86.7% of the patients who never required augmentation recovered (78 of 90). These proportions differed significantly (χ 2 =21.82, df=2, p<0.001).

We also examined whether augmentation exacted a higher toll on the quality of recovery by examining side effect levels experienced at the final treatment point (i.e., when recovery status was declared). Independent of whether the patients met the recovery criteria (i.e., with control for this variable), patients receiving augmentation because of inadequate treatment response showed the highest level of side effects (Utvalg for Kliniske Undersogelser score: mean=5.7, SD=3.4), followed by patients receiving augmentation after early relapse (mean=4.6, SD=3.0) and patients not requiring augmentation (mean=3.8, SD=3.1) (F=3.72, df=2, 153, p=0.03). There were no differences in side effect levels as a function of recovery status (with control for receipt of augmentation); the mean score was 5.3 (SD=3.4) for the patients who did not recover and 4.2 (SD=3.2) for the recovered patients (F=0.38, df=1, 153, p=0.54).

Among the total of 69 patients who received augmentation, those who required consecutive treatment with more than one augmenting agent were somewhat less likely to recover: 59.6% of the 47 patients treated with one augmenting agent recovered, 50.0% of the 12 treated with two agents recovered, and 40.0% of the 10 patients treated with all three agents recovered. However, these recovery rates did not differ significantly from one another (χ 2 =1.43, df=2, p=0.49).

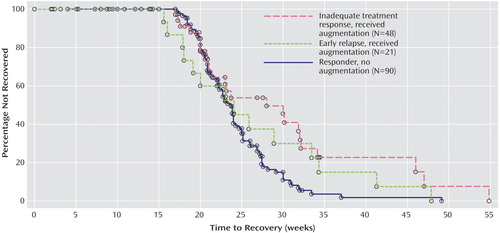

Once augmentation is begun, an important clinical issue concerns how long it will take for patients to recover. We evaluated this by comparing time to recovery from the first day of augmentation (i.e., with the clock set back to zero at augmentation inception for any individual requiring it) to total recovery time among individuals not requiring augmentation. Figure 2 plots these data for the two groups of patients who received augmentation and the group who never required it. There were significant between-group differences in time to recovery (log rank χ 2 =8.17, df=2, p=0.02). Patients who required augmentation because of inadequate treatment response took longer to recover after the onset of augmentation (median of 28 weeks) than either of the other two groups (median of 24 weeks in each group).

a For patients who received augmentation, time to recovery began at the first day of augmentation. Log-rank test for group differences: χ 2 =8.17, df=2, p=0.02. Reasons for censoring—group with inadequate treatment response: one patient withdrew consent, three experienced significant side effects or incident medical problems, and three were declared nonrecovered and were terminated from the study; group with early relapse: seven patients withdrew consent, 10 experienced significant side effects or incident medical problems, and six were declared nonrecovered and were terminated; responder group: five patients withdrew consent, five experienced significant side effects or incident medical problems, and two died from myocardial infarctions (both had preexisting heart disease).

What Predicts Longer Time to Recovery After Augmentation Begins?

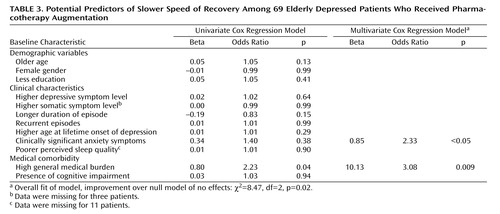

We examined whether, among the 69 patients who received augmentation, there were baseline characteristics that predicted time to recovery after augmentation was begun. We took a conservative approach to these analyses given the small number of subjects. Thus, we initially examined each potential predictor’s association with time to recovery in separate univariate Cox regression analyses. Variables showing at least a moderate association with time to recovery in the univariate analyses (defined as a regression weight with an absolute value of at least 0.30, corresponding to an odds ratio of 1.35) were eligible for inclusion in the final multivariate analysis. As shown in the univariate analysis columns of Table 3 , only two variables met this criterion: higher baseline medical burden and the presence of clinically significant anxiety. Results shown in the multivariate analysis columns of Table 3 indicate that in the multivariate Cox model, both variables were significantly associated with slower speed of recovery.

Discussion

Our findings add significantly to the sparse literature concerning the utility of augmentation pharmacotherapy in late-life depression. Patients who received augmentation in our open trial because of inadequate response or early relapse during treatment with paroxetine plus interpersonal psychotherapy were less likely to recover than individuals who did not require augmentation: the percentages of patients recovering were 50.0% for those receiving augmentation because of inadequate treatment response, 66.7% for those receiving augmentation after an early relapse, and 86.7% of those who never required augmentation. However, these findings provide two reasons not to be pessimistic about augmentation. First, the recovery rates among patients receiving augmentation in our study are considerably better than the remission rates of 14% to 30% observed in the few studies of long-term outcomes of augmentation in young to middle-aged adults with inadequate responses to SSRI treatment (18 , 32 , 33) . While neither these studies nor ours were placebo-controlled trials, our findings appear to belie the notion that older adults are less likely than younger adults to achieve benefits (relative to the risks) of aggressive treatment strategies such as augmentation (9) . Clearly, some older adults will be unwilling or unable to tolerate augmentation because of comorbid medical conditions, as we observed in our study group. Furthermore, we found augmentation to be associated with a statistically significant (although clinically modest) elevation in side effects. However, when administered judiciously, augmentation may have value in facilitating recovery.

The second reason to avoid undue pessimism stems from a consideration of the likelihood of recovery in patients receiving augmentation in the context of our complete cohort of 195 older adults, including individuals who needed but did not receive augmentation. Thus, from an overall, intent-to-treat perspective, 40.0% of all patients (78 of 195) started treatment and recovered without augmentation. Including patients receiving augmentation raises the overall rate of recovery to 59.5% ([78+38]/195) in the cohort. This increment in recovery is clinically noteworthy. It suggests the importance of conducting controlled investigations in older adults to definitively determine the role of augmentation in facilitating recovery. In the absence of a placebo-controlled trial, it remains unclear as to whether increments in recovery rate associated with augmentation reflect a true, specific effect of this strategy, as opposed to a placebo-type effect or an effect attributable simply to the passage of time (i.e., greater length of treatment).

While we view the results among individuals receiving augmentation as encouraging, our data also reflect the major impediments to the use of augmentation in older adults. Despite our multiagent augmentation strategy, in which medical burden was specifically taken into account in the decision about which augmenting medication would be best tolerated by a given patient, over one-third of our patients who were eligible for augmentation did not receive it and were thus removed from the study. Most of these individuals either were unwilling to accept augmentation or had medical conditions that precluded continuation in the study, including receipt of any augmenting agents. Systematic investigations of the effectiveness of other treatment options for such patients are needed. For example, switching to another antidepressant after failure of an initial SSRI is one possibility. Switching medications may have some benefits over augmentation for older adults (e.g., allowing for a simpler medication regimen and hence possibly better adherence, avoiding drug-drug interactions, lower economic cost) (29) . However, only limited data are available regarding this strategy’s potential effectiveness, relative to augmentation algorithms (14 , 18) .

An evaluation of the potential utility of augmentation demands consideration not only of the likelihood of recovery, but of recovery speed. We found that patients receiving augmentation took longer to achieve recovery than those not requiring augmentation. In particular, those showing inadequate treatment response were the slowest to recover even when recovery time was calculated from the start of augmentation. Thus, a clinician should be prepared to wait at least 28 weeks for recovery in these patients, compared to the 24-week median recovery time in all remaining individuals. This group of patients included those whose depression levels showed no change or worsened, as well as those who showed only mild improvement in depression levels. As such, they most closely fit the definition of “treatment resistant” (2) , and they appear to be the patient subgroup most in need of more effective strategies to promote timely recovery. One approach might be to identify patients at highest risk for treatment resistance and then apply augmentation as first-line therapy, rather than waiting to observe a prolonged lack of response (34) . However, this may be difficult to implement in practice given other complicating factors, such as medical burden. Indeed, baseline medical burden and comorbid anxiety each independently presaged a slower speed of recovery in patients receiving augmentation.

There are several limitations in our study. Our study group was primarily European American, with ethnic group minority representation only from African Americans. We have already noted that our examination of augmentation was not placebo controlled, and this limits the inferences that can be drawn. In addition, although augmentation was administered by means of a standardized protocol, it was delivered by nonblinded clinicians and the patients were informed regarding its anticipated effects. Finally, because of our limited group sizes within the major study subgroups, it was not possible to make finer-grained distinctions within the groups of patients who required augmentation regarding their precise patterns of poor response to treatment. For example, patients who show absolutely no change, or even worsening depression, with treatment may well differ from those who show some modest but far from adequate improvement. Among those with modest improvement, the precise degree of change may matter as well in predicting who will accept augmentation and the likelihood and timing of recovery after the start of augmentation.

In conclusion, our findings suggest the promise of augmentation strategies in the treatment of late-life depression, but they indicate that the application of these strategies will ultimately depend on older adults’ medical status and personal preferences for treatment. Within these constraints, we recommend that controlled studies of the efficacy of augmentation strategies be undertaken. Such studies are needed both in the context of failure of initial SSRI treatment and in first-line attempts to promote improved likelihood and speed of recovery.

1. Whyte EM, Dew MA, Gildengers A, Lenze EJ, Bharucha A, Mulsant BH, Reynolds CF III: Time course of response to antidepressants in late-life major depression: therapeutic implications. Drugs Aging 2004; 21:531–554Google Scholar

2. Little JT, Reynolds CF III, Dew MA, Frank E, Begley AE, Miller MD, Cornes C, Mazumdar S, Perel JM, Kupfer DJ: How common is resistance to treatment in recurrent, nonpsychotic geriatric depression? Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1035–1038Google Scholar

3. Reynolds CF III, Frank E, Perel JM, Mazumdar S, Dew MA, Begley A, Houck PR, Hall M, Mulsant B, Shear MK, Miller MD, Cornes C, Kupfer DJ: High relapse rate after discontinuation of adjunctive medication for elderly patients with recurrent major depression. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:1418–1422Google Scholar

4. Alexopoulos GS: Depression in the elderly. Lancet 2005; 365:1961–1970Google Scholar

5. Gallo JJ, Bogner HR, Morales KH, Post EP, Ten Have T, Bruce ML: Depression, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and two-year mortality among older, primary-care patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005; 13:748–755Google Scholar

6. DeBattista C: Augmentation and combination strategies for depression. J Psychopharmacol 2006; 20(3 suppl):11–18Google Scholar

7. Fava M, Rush AJ: Current status of augmentation and combination treatments for major depressive disorder: a literature review and a proposal for a novel approach to improve practice. Psychother Psychosom 2006; 75:139–153Google Scholar

8. Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, Thase ME, Quitkin F, Warden D, Ritz L, Nierenberg AA, Lebowitz BD, Biggs MM, Luther JF, Shores-Wilson K, Rush AJ, STAR*D Study Team: Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:1243–1252Google Scholar

9. Lotrich FE, Pollock BG: Aging and clinical pharmacology: implications for antidepressants. J Clin Pharmacol 2005; 45:1106–1122Google Scholar

10. Boyle A: A novel approach to the psychopharmacologic treatment of insomnia in depression. Med Hypotheses 2004; 63:26–30Google Scholar

11. Lavretsky H, Kumar A: Methylphenidate augmentation of citalopram in elderly depressed patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001; 9:298–303Google Scholar

12. Xiong GL, Christopher EJ, Goebel J: Modafinil as an alternative to methylphenidate as augmentation for depression treatment. Psychosomatics 2005; 46:578–579Google Scholar

13. Finch EJL, Katona CLE: Lithium augmentation in the treatment of refractory depression in old age. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1989; 4:41–46Google Scholar

14. Flint AJ, Rifat SL: The effect of sequential antidepressant treatment on geriatric depression. J Affect Disord 1996; 36(3–4):95–105Google Scholar

15. Lafferman J, Solomon K, Ruskin P: Lithium augmentation for treatment-resistant depression in the elderly. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1988; 1:49–52Google Scholar

16. van Marwijk HWJ, Bekker FM, Nolen WA, Jansen PAF, van Nieuwkerk JF, Hop WCJ: Lithium augmentation in geriatric depression. J Affect Disord 1990; 20:217–223Google Scholar

17. Zimmer B, Rosen J, Thornton JE, Perel JM, Reynolds CF III: Adjunctive lithium carbonate in nortriptyline-resistant elderly depressed patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1991; 11:254–256Google Scholar

18. Whyte EM, Basinski J, Farhi P, Dew MA, Begley A, Mulsant BH, Reynolds CF III: Geriatric depression treatment in nonresponders to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65:1634–1641Google Scholar

19. Reynolds CF III, Dew MA, Pollock BG, Mulsant BH, Frank E, Miller MD, Houck PR, Mazumdar S, Butters MA, Stack JA, Schlernitzauer MA, Whyte EM, Gildengers A, Karp J, Lenze E, Szanto K, Bensasi S, Kupfer DJ: Maintenance treatment of major depression in old age. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:1130–1138Google Scholar

20. Frank E, Frank N, Cornes C, Imber SD, Miller MD, Morris SM, Reynolds CF III: Interpersonal psychotherapy in the treatment of late-life depression, in New Applications of Interpersonal Psychotherapy. Edited by Klerman GL, Weissman MM. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993, pp 167–198Google Scholar

21. Lingjaerde O, Ahlfors UG, Bech P, Dencker SJ, Elgen K: The UKU side effect rating scale: a new comprehensive rating scale for psychotropic drugs and a cross-sectional study of side effects in neuroleptic-treated patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1987; 334:1–100Google Scholar

22. Derogatis LR: Brief Symptom Inventory: Administration, Scoring and Procedures Manual, 3rd ed. Minneapolis, National Computer Systems, 1993Google Scholar

23. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF III, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ: The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 1989; 28:193–213Google Scholar

24. Miller MD, Paradis CF, Houck PR, Mazumdar S, Stack JA, Rifai AH, Mulsant B, Reynolds CF III: Rating chronic medical illness burden in geropsychiatric practice and research: application of the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale. Psychiatry Res 1992; 41:237–248Google Scholar

25. Mattis S: Dementia Rating Scale (DRS) Manual. Odessa, Fla, Psychological Assessment Resources, 1988Google Scholar

26. First M, Spitzer RL, Gibbon W, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I), version 2.0. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1995Google Scholar

27. Hamilton M: Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1967; 6:278–296Google Scholar

28. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Google Scholar

29. Mulsant BH, Alexopoulos GS, Reynolds CF III, Katz IR, Abrams R, Oslin D, Schulberg HC, PROSPECT Study Group: Pharmacological treatment of depression in older primary care patients: the PROSPECT algorithm. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001; 16:585–592Google Scholar

30. Waldman E, Potter JF: A prospective evaluation of the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale. Aging Clin Exp Res 1992; 4:171–178Google Scholar

31. Jurica PJ, Leitten CL, Mattis S: Dementia Rating Scale-2 (DRS-2) Manual. Odessa, Fla, Psychological Assessment Resources, 2001Google Scholar

32. Iosifescu DV, Nierenberg AA, Mischoulon D, Perlis RH, Papakostas GI, Ryan JL, Alpert JE, Fava M: An open study of triiodothyronine augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66:1038–1042Google Scholar

33. Papakostas GI, Petersen TJ, Green C, Iosifescu DV, Yeung AS, Nierenberg AA, Fava M, Posternak MA: A description of next-step switching versus augmentation practices for outpatients with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder enrolled in an academic specialty clinic. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2005; 17:161–165Google Scholar

34. Taragano FE, Bagnatti P, Allegri RF: A double-blind, randomized clinical trial to assess the augmentation with nimodipine of antidepressant therapy in the treatment of “vascular depression.” Int Psychogeriatr 2005; 17:487–498Google Scholar