Dismantling Structural Racism in Psychiatry: A Path to Mental Health Equity

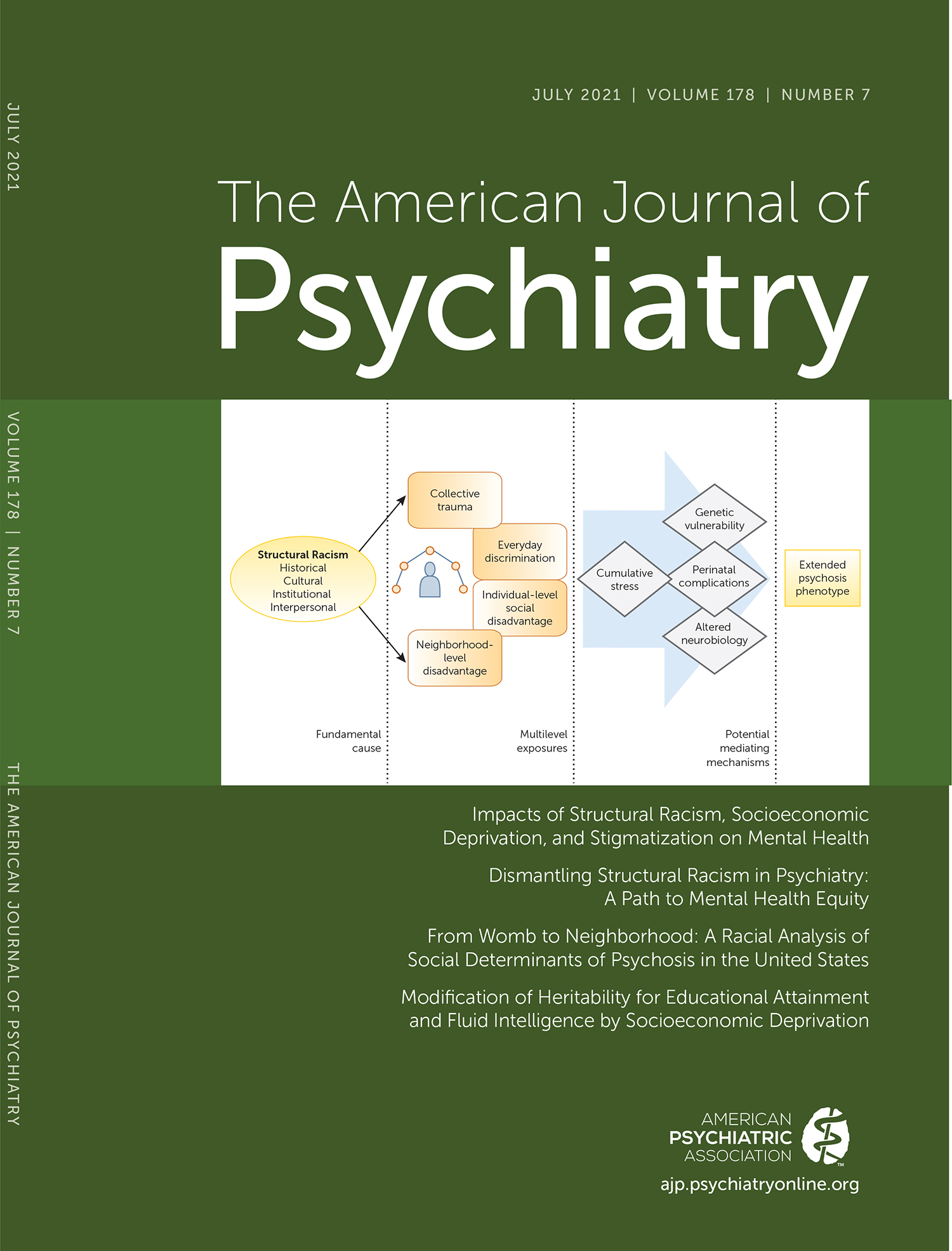

Examples of racial injustice (including COVID-19 inequities, police killings of Black people, and mass shootings targeting specific racial and ethnic groups) are prevalent in U.S. society. There is a growing understanding that trauma caused by racial injustice has extensive impacts on mental health. There is also increasing evidence that the social determinants of mental health—defined by the World Health Organization as “the societal, environmental, and economic conditions that impact and affect health outcomes” (1)—are primarily responsible for the well-documented mental health inequities seen among various racial and ethnic population groups in the United States.

While this article focuses on the negative mental health impacts of social injustice on racially and ethnically minoritized populations (a term used to acknowledge that systems of oppression place populations into “minority” status) (2), it is important to note that many populations are subject to the harmful mental health impacts of oppression and subjugation. Women, LGBTQ populations (especially transgender people), certain religious groups, people with disabilities, and people with lower income all experience similar impacts of mental health inequities as the result of social injustice. Furthermore, the intersectionality (a term used to define the cumulative effects of race, class, gender, sexuality, ability, and other marginalized identities on social status and health) of these oppressed identities can compound harmful mental health impacts, especially when recognizing that people with serious mental illness and substance use disorders are themselves an oppressed and marginalized population (3).

Data on the prevalence rates of mental illness and substance use disorders across racial and ethnic groups vary widely. The reasons for this are multifactorial but are situated largely in the imprecision of racial categorizations and measurements of race (4). Despite this inconsistency, certain inequities in psychiatric diagnoses are persistent and enduring. Explanations for these differences have often been incorrectly framed in models of biological determinism (i.e., the false belief that racial groups are biologically and genetically different) or cultural determinism (i.e., the false belief that differences in racial groups are primarily the result of cultural factors), with less attention given to the true causes of these inequities: social injustice and structural racism (5).

KEY CONCEPTS

Conceptualizing Race and Structural Racism

Although the term has outsized significance in U.S. society, the definition of race remains poorly understood. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary definition of race includes six previous definitions that are classified as archaic, obsolete, or dated, reflecting the fact that the definition of race has transformed with changing times and context (6). Throughout history, racial classification systems have been imprecise and even bizarre, including such strange conventions in the United States as the “one-drop rule” and broad Census categorizations such as “octoroon” for anyone with “one-eighth black blood” and “Hindu” for anyone of Asian Indian descent, regardless of their religion (7). While the social construction of race has long been advanced as a justification for racism, this conceptualization has remained somewhat resistant to acceptance over time. In her book The Nature of Race, the sociologist Ann Morning presents a working definition of race as “a system for classifying human beings that is grounded in the belief that they embody inherited and fixed biological characteristics that identify them as members of racial groups” (8).

Similar to race, no single accepted definition exists for structural racism (9). However, key shared themes of definitions are captured well by the Aspen Institute, which defines structural racism as “a system in which public policies, institutional practices, cultural representations, and other norms work in various, often reinforcing ways to perpetuate racial group inequity. It identifies dimensions of our history and culture that have allowed privileges associated with ‘whiteness’ and disadvantages associated with ‘color’ to endure and adapt over time” (10). Within psychiatry, this system has led to the misdiagnosis, overdiagnosis, and poor treatment and management of people of color with mental health and substance use disorders and ultimately relates directly to the mental health inequities seen among populations (5).

Mental Health Disparities and Inequities

Although sometimes used interchangeably, the terms “disparities” and “inequities” have separate meanings. While health disparities are differences in health status among distinct segments of the population, health inequities are defined as disparities in health that are a result of systemic, avoidable, and unjust policies and practices that create barriers to opportunity (11). By describing the cause or origin of these differences in health, the definition of inequities is more precise. Because the term disparities does not identify the cause of the difference, there is a tendency to default to traditional and historical explanations for difference, which include seating the pathology with an individual or a population. In medicine and psychiatry, we have reported differences in outcomes without regard for or exploration of the cause or origin of these outcomes. Perhaps some consider these differences to be caused by innate biological or cultural distinctions, rather than systemic, avoidable, and unjust social and economic policies and practices. For example, consider the often-reported disparity that Indigenous populations have higher rates of alcohol use disorder than other populations. Scientific theory has postulated that this disparity is at least partially genetic (12) and innate, or primarily driven by a biological cause (with some limited interaction of environmental factors), rather than considering the structurally racist policies that marginalized and oppressed Indigenous populations throughout history. These inequitable policies ultimately led to historical trauma and even present-day oppression and racism. From this oppression and racism, the unjust distribution of opportunity has led to a host of social determinants of mental health, including adverse childhood experiences, discrimination, exposure to violence and conflict, low education, unemployment, poverty, and other factors. These social determinants of mental health better explain differences in prevalence rates of alcohol use disorders in Indigenous populations than biological causes (13). Scientists often highlight that little data or direct evidence exists to support theories of unjust social and economic policies and practices, without acknowledging the centuries of structurally racist policies that have led to an inability to consider the complexity of the causes, a dearth of researchers with an interest in studying these minoritized populations, and the lack of interest among predominantly White, male peer reviewers in accepting and publishing these findings (14).

What Is Social Justice?

Although considered by some to be a controversial and political topic, the concept of social justice is essential when attempting to achieve mental health equity. Philosopher David Miller defined social justice as the equitable distribution of good (or advantages) and bad (or disadvantages) in society and, in particular, how advantages and disadvantages should be justly distributed in society (15). This is coupled with John Rawls’s definition, which can be summarized as “assuring the protection of equal access to liberties, rights, and opportunities, as well as taking care of the least advantaged members of society” (15). Thus, social justice is critical to improving outcomes in health for populations, particularly those populations that are most vulnerable and most oppressed in society, which includes people with serious mental illnesses and substance use disorders.

Therefore, by extension, social injustice is the unfair and unjust distribution of advantages and disadvantages in society. The underlying factors that lead to social injustice are the social norms and public policies of society (16). These mindsets and resulting laws set the stage for social injustice, which then sets the context for the development of various social determinants of mental health, which then leads to a host of risk factors for mental health problems, ultimately resulting in adverse mental health outcomes and inequities in mental health.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT OF PSYCHIATRIC PSEUDOSCIENCE

Despite ample evidence to support the key concepts presented above, many psychiatrists and other mental health professionals still believe in the concept of biological determinism. Such beliefs, although clearly and consistently proven false, are remarkably persistent, with medical students harboring these same biases (e.g., that Black people have thicker skin and fewer nerve endings than White people) to this day (17). These beliefs are extensions of traditional thoughts handed down in medical teaching throughout history.

In 1776, the signers of the Declaration of Independence endorsed the words written by Thomas Jefferson, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness” (18). Clearly, these Founding Fathers did not mean that all people were created equal. While exact numbers are difficult to determine with accuracy, it is accepted that at least two-thirds of the 56 signers of the Declaration of Independence owned slaves (19). Among the signers of the Declaration, Benjamin Rush (often considered the “Father of American Psychiatry”), while being a self-described abolitionist, also taught medical students that black skin was a form of leprosy, which he described as “negritude” (20).

With the ratification of the U.S. Constitution in 1788, structural racism was codified into the foundation and structure of the country. The “three-fifths clause” established different levels of congressional representation based on race, with Indigenous people not counting at all and enslaved Africans counting as three-fifths of a person each toward apportionment of a state’s congressional delegation. While the motives for and outcomes of the inclusion of this clause in the Constitution are complex, the result was the differential valuation of people of different constructed racial categories, which ensured inequitable congressional representation and allowed for the passage of laws that advantaged certain populations and disadvantaged others (21).

Over 60 years after the ratification of the U.S. Constitution, physician Samuel Cartwright played a prominent role in the rise of racism in the field of psychiatry. His descriptions and characterizations of mental health conditions in enslaved Africans, particularly drapetomania, which he described as the illness of enslaved people wanting to run away and escape captivity, and dysaesthesia aethiopica, a disease of “rascality” or laziness in enslaved Africans, were the beginning justifications of pathologizing normal behavioral responses to trauma and oppression. These “diseases” paved the way for long-standing rationalization of harsh, inhumane treatment of mental illnesses in communities of color; Cartwright’s prescribed treatment for both conditions was whipping (22). The historical origins of racism in psychiatry set the stage for instances of structural racism that impact the diagnosis, management, and treatment of mental illnesses and substance use disorders to this day.

MODERN EXAMPLES OF STRUCTURAL RACISM IN PSYCHIATRY

Residential Segregation

With the creation of the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) in 1933, the federal government codified and structurally entrenched segregation in over 200 cities in the United States. HOLC created maps in which communities of color were designated by red lines as poor investment opportunities. Meanwhile, those communities that were predominantly White received investments in infrastructure and infusions of financial supports and planning (23). The “built environment” (defined as the human-made physical structures where we live, work, and play) in these White communities supported mental and physical health, and schools, hospitals, and other social services reflected these investments (24). Racial covenants helped to preserve the segregation of these communities. Those communities of color that were redlined saw systematic disinvestment; some extreme cases were accompanied by withdrawal of infrastructure and community supports, a policy known as “planned shrinkage” (25). Hospitals, clinics, well-funded schools, and even grocery stores were all scarce in these redlined communities, leading to a host of social determinants of mental health, including unemployment, food insecurity, increased crime, flourishing underground economies, and area-level poverty. These social determinants of mental health are associated with increased rates of maternal depression, anxiety, alcohol use disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder (9). Furthermore, as a result of residential segregation, psychiatrists and therapists were (and are) less likely to be located in low-income neighborhoods with greater percentages of Black and Latinx residents (when compared with high-income neighborhoods with less than 1% of Black or Latinx residents) (26).

Although residential segregation was outlawed in 1968 by the Fair Housing Act, its impacts on health are remarkably enduring. A recent geographic analysis examining access to COVID-19 vaccine administration facilities found 69 counties in the United States where Black residents had a higher risk than White residents of having to drive more than 1 mile to get to the closest vaccination site (27). White people have received at least one COVID-19 vaccine dose at a rate 1.6 times higher than Black people and 1.5 times higher than Latinx people (28). The general explanation of these “disparities” defaults to more cultural and attitudinal explanations, such as vaccine hesitancy, rather than emphasizing how structurally racist policies that led to residential segregation (created by systemic, avoidable, and unjust social and economic policies and practices) impact vaccination rates.

The “War on Drugs”

Moral panic is defined as occurring when “a condition, episode, person or group of persons emerges to become defined as a threat to societal values and interests” (29). In the early 1980s, a distinctive moral panic set in regarding people who used crack cocaine, a drug that was commonly associated with Black people (30). The media and politicians lamented Black men who used crack cocaine as dangerous criminal “dope fiends,” and Black women with crack cocaine use disorder were depicted as depraved “crack mothers” who were willing to sacrifice the health and safety of their children for the drug (30, 31). As a result of these negative social norms about people with crack cocaine use disorder, public policies were enacted to punish this population. The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 created a 100-to-1 disparity between crack and powder cocaine—meaning that 1 g of crack cocaine (a drug primarily used by people of lower incomes, many of whom are Black people) carried the same federal prison sentence as 100 g of powder cocaine (a drug primarily used by people of higher incomes, many of whom are White people), despite these drugs being the same chemical compound (32).

Additionally, crack cocaine use disorder was viewed primarily as a criminal justice problem, not as a public health problem, and people with crack cocaine use disorder were commonly incarcerated rather than referred for treatment. Structural racism is also relevant in the minimal availability of substance use disorder treatment, which is most easily accessed either via religious settings (often subtly implying some type of moral failing rather than a health condition) or in jails and prisons. In A Plague of Prisons: The Epidemiology of Mass Incarceration in America, Ernest Drucker notes that “the fundamental clinical accountability of drug treatment professionals to individual patients has been subordinated to the goals of the criminal justice system” (33).

In considering how the War on Drugs epitomizes structural racism, the social norms about crack cocaine users and the subsequent public policies enacted as a result of these social norms can be contrasted with those seen with the opioid epidemic. Generally, medical professionals view opioid use disorder as a public health problem and not a criminal justice problem. Men and women with opioid use disorder are not viewed as criminals but as inherently well-meaning people who need treatment to save their lives (34). A common critique against the argument that structural racism persists today is that perhaps medical professionals may have learned from past mistakes and that is why we treat opioid use disorder more effectively. However, jail sentencing disparities for crack and powder cocaine still exist (although the disparity has been reduced from 100:1 to 18:1), and deaths associated with crack cocaine use disorder are still at epidemic levels (particularly in the Black community), with little media attention or outcry for interventions as observed with opioid use disorder (35).

The structurally racist policies of the War on Drugs have led to the mass incarceration of people of color for substance use disorders. Mass incarceration leads to a host of other social determinants of mental health, both individually and generationally, including lower rates of employment and higher rates of poverty among those released from prison, and for families, adverse childhood experiences of growing up with an incarcerated parent (36). These social determinants of mental health have been implicated in the increased risk of major depressive disorder, substance use disorders, and even certain personality disorders (37).

Mental Health Care Access

Recent data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration indicate that in 2018, 69% of Black adults and 67% of Latinx adults did not receive any treatment for mental health problems. For serious mental illness, the numbers are equally concerning, with 42% of Black adults and 44% of Latinx adults not receiving any treatment. When considering substance use disorders, the numbers are alarming, with 88% of Black adults and 89% of Latinx adults not receiving any treatment (38, 39).

While it is tempting to assume cultural and patient-level explanations for why Black and Latinx adults are not accessing mental health care at such high rates (common explanations include greater rates of stigma and lack of insight), in surveys of Black adults, cost was cited as the most common reason that people do not seek mental health services (40), and previous studies have found that Black and Latinx people may have more positive attitudes toward mental health treatment-seeking than White people (41).

Historically, structurally racist policies have driven opposition to universal health care (42), and discrimination and segregation were standard practice in many professional societies. For example, the American Medical Association excluded Black physicians from the organization until it was forced by the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to accept them, which contributed to the low levels of Black physicians in the United States that persists today. Opposition to universal health care persists to this day, and for people with mental illnesses and substance use disorders, greater inequities built into the structures of the mental health care system ensure that minoritized populations access services at significantly lower rates than White populations.

Within the United States, the mental health system is a broken patchwork of siloed services, resulting in a significant number of psychiatrists who do not take insurance, because of a number of factors, including low reimbursement rates (43). These policies and practices govern a deeply inequitable, socially unjust mental health system in the United States, where minoritized communities are unable to afford high-quality mental health services. This ultimately leads to discrimination against people with mental health problems, particularly those with additional minoritized identities.

DISMANTLING STRUCTURAL RACISM IN PSYCHIATRY

Over 50 years ago, in the American Journal of Psychiatry, Sabshin et al. laid out clear plans (directed specifically at White psychiatrists) to address institutional racism in psychiatry (44). Notably, they wrote:

“We are asking white psychiatrists to become increasingly aware of how their everyday practices continue to perpetuate institutional white racism in psychiatry and to support the search for realistic solutions to providing psychiatric services to black people. We ask white psychiatrists to provide strong sanction and support to these efforts. This means making available the necessary resources of money, manpower, and authority—and not just in the current token amounts. It means not defending the vested white interests in old institutional forms of professionalism when new strategies and roles are suggested; it means a significant reduction in economic barriers to psychiatric care; it means relinquishing negative stereotypes of the black patient; it means truly sharing administrative decision making with black colleagues and black communities.”

Unfortunately, most if not all of these recommendations were largely ignored. This time, the hope is that there is a stronger political will and a greater desire to put forth individual effort within psychiatry to seek an end to structural racism and to advance mental health equity for all. This work can be accomplished through several important steps.

Education and Self-Reflection

Because of the enduring nature of structural racism, the concepts discussed here are not typically taught in medical schools or other health professional schools. And yet, a rich body of research exists, often in other sectors, including anthropology, sociology, and critical race theory (23). To begin to enhance knowledge and understanding of the impacts of structural racism on mental health, psychiatrists and other mental health professionals must commit to developing greater cultural humility and structural competence. Cultural humility operates under three important tenets: 1) committing to a lifelong process of self-evaluation and self-critique, 2) desiring to fix power imbalances between providers and clients, and 3) developing community partnerships to advocate within the larger organizations within which we participate (45). Structural competence is the ability to discern how downstream clinical symptoms, problems, and diseases are influenced by upstream social determinants of mental health (46). Similarly, a rich body of literature exists to help guide psychiatrists’ and other mental health professionals’ greater acquisition of knowledge of the concepts of social injustice and mental health equity (23).

Changing Social Norms

Because our underlying beliefs about people from different racial backgrounds have been shaped by a “miasma” of structural racism, work must be done to help individuals and populations unlearn and challenge their existing belief systems about the inherent biological and cultural inferiority of racial and ethnic minority groups. Individually, people can begin to change their own thinking about this by getting in the habit of observing and challenging one’s own implicit biases, using techniques that help people confront and minimize their negative bias toward certain racial and ethnic groups (47). Once the internal work begins, it can be expanded to systems-level interventions by enforcing social norms of inclusion and equity in personal and professional settings. Many people who possess erroneous personal beliefs about the inferiority of certain racial groups simply lack accurate information and experiences to counter these beliefs. Thus, when someone violates social norms of inclusion, education can be critical, and includes “calling in” those who express interpersonally racist views. However, because there is a small subset of the population that will continue to believe in the supremacy of White people over all other races of people, legislation becomes a powerful tool to change social norms. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, gender identity, national origin, and sexual orientation and thus should be enforced to prevent people from exercising socially exclusive policies and climates in professional settings, including psychiatric hospitals and mental health clinics. Leaders can also enforce social inclusion in settings by utilizing policies to remove people who consistently express racist or socially exclusionist beliefs from professional settings that would harm vulnerable populations, including students and patients. Similarly, providers should evaluate and break down any unnecessary hierarchies that are driving social norms that one population or group of people is worthy of greater advantage or regard than other populations or groups of people.

Addressing Public Policies

Through an understanding of how social injustice and the social determinants of mental health ultimately lead to poor mental health outcomes and mental health inequities, psychiatrists and other mental health professionals can begin to understand the power of advocating for policies that are seemingly not directly related to mental health at all. For example, policies that address the social determinants of mental health, including stable housing, unemployment benefits, access to healthy food, and ending the criminalization of substance use disorders can all help to dismantle structural racism and improve health outcomes (48). To accomplish this work, psychiatrists and other mental health professionals must commit to communicating with elected officials to help pass policies that focus on the social determinants and must also form cross-sector collaborations with stakeholders at various levels in the community—all while advocating for equitable representation by minoritized populations in positions of power and influence (both within the field of psychiatry and in communities).

Finally, if the death of George Floyd shifted something in U.S. society, out of the senseless tragedy of it—and the many thousands of innocent people who lost their lives before and those who will lose their lives after as the result of structural racism—hope remains that a growing number of psychiatrists and mental health professionals are recognizing the unacceptable nature of racial injustice and its impact on mental health. Because psychiatrists and other mental health professionals desire to promote the mental health and well-being of all people, we all have a moral responsibility to speak out against racial injustice wherever we encounter it, recognizing, in the words of Frederick Douglass, that “power concedes nothing without a demand” (49).

1.

2. : Time to reconsider the word minority in academic medicine . Journal of Best Practices in Health Professions Diversity 2019 ; 12 : 72 – 83 Google Scholar

3. : Marginalized identities, discrimination burden, and mental health: empirical exploration of an interpersonal-level approach to modeling intersectionality . Soc Sci Med 2012 ; 75 : 2437 – 2445 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. : The quality of data on “race” and “ethnicity”: implications for health researchers, policy makers, and practitioners . Race Soc Probl 2014 ; 6 : 214 – 236 Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Shim RS , Vinson SY (eds): Social (In)Justice and Mental Health. Washington, DC , American Psychiatric Association Publishing , 2021 Google Scholar

6.

7. : Racial classifications in the US Census: 1890–1990 . Ethn Racial Stud 1993 ; 16 : 75 – 94 Crossref, Google Scholar

8. : The Nature of Race: How Scientists Think and Teach About Human Difference. Berkeley , University of California Press , 2011 Crossref, Google Scholar

9. : How Structural racism works: racist policies as a root cause of U.S. racial health inequities . N Engl J Med 2021 ; 384 : 768 – 773 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10.

11. :

12. : Evidence for a genetic component for substance dependence in Native Americans . Am J Psychiatry 2013 ; 170 : 154 – 164 Link, Google Scholar

13. : Native Americans and alcohol: past, present, and future . J Gen Psychol 2006 ; 133 : 435 – 451 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. : Responsibility of medical journals in addressing racism in health care . JAMA Netw Open 2020 ; 3 : e2016531 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. : Assessing criminal justice practice using social justice theory . Soc Justice Res 2010 ; 23 : 77 – 97 Crossref, Google Scholar

16. : The social determinants of mental health: psychiatrists’ roles in addressing discrimination and food insecurity . Focus Am Psychiatr Publ 2020 ; 18 : 25 – 30 Medline, Google Scholar

17. : Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2016 ; 113 : 4296 – 4301 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18.

19. : Fact-check: They signed the Declaration of Independence—but nearly three-quarters also owned slaves. Chicago Sun-Times, September 10, 2019 . https://chicago.suntimes.com/2019/9/10/20859458/fact-check-declaration-independence-slaves-trumbull-painting-arlen-parsa Google Scholar

20. : Négritude’s contretemps: the coining and reception of Aimé Césaire’s neologism . Philological Quarterly 2020 ; 99 : 377 – 398 Google Scholar

21. : White Racism: The Basics. New York , Routledge , 2000 Google Scholar

22. : Running away from drapetomania: Samuel A Cartwright, medicine, and race in the antebellum South . J South Hist 2018 ; 84 : 579 – 614 Crossref, Google Scholar

23. :

24. : Inequality set in concrete: physical resources available for care at hospitals serving people of color and other US hospitals . Int J Health Serv 2020 ; 50 : 363 – 370 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. : Serial forced displacement in American cities, 1916–2010 . J Urban Health 2011 ; 88 : 381 – 389 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. : Geographic access to specialty mental health care across high- and low-income US communities . JAMA Psychiatry 2017 ; 74 : 476 – 484 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. : Access to Potential COVID-19 Vaccine Administration Facilities: A Geographic Information Systems Analysis. February 2, 2021 . https://s8637.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Access-to-Potential-COVID-19-Vaccine-Administration-Facilities-2-2-2021.pdf Google Scholar

28. : Latest data on COVID-19 vaccinations race/ethnicity. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/latest-data-on-covid-19-vaccinations-race-ethnicity/ Google Scholar

29. : Folk Devils and Moral Panics: The Creation of the Mods and Rockers. London , Routledge , 2002 Google Scholar

30. :

31. : Lies, Damned Lies, and Drug War Statistics: A Critical Analysis of Claims Made by the Office of National Drug Control Policy. Albany , State University of New York Press , 2014 Google Scholar

32. : Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions . Lancet 2017 ; 389 : 1453 – 1463 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. : A Plague of Prisons: The Epidemiology of Mass Incarceration in America. New York , New Press , 2013 Google Scholar

34. : White opioids: pharmaceutical race and the war on drugs that wasn’t . Biosocieties 2017 ; 12 : 217 – 238 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. : Trends in US drug overdose deaths in non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic White persons, 2000–2015 . Ann Intern Med 2018 ; 168 : 453 – 455 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. : Mass incarceration, public health, and widening inequality in the USA . Lancet 2017 ; 389 : 1464 – 1474 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. : The Social Determinants of Mental Health. Washington, DC , American Psychiatric Association Pubishing , 2015 Google Scholar

38.

39.

40. : Mental health care among Blacks in America: confronting racism and constructing solutions . Health Serv Res 2019 ; 54 : 346 – 355 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. : Race-ethnicity as a predictor of attitudes toward mental health treatment seeking . Psychiatr Serv 2009 ; 60 : 1336 – 1341 Link, Google Scholar

42. : More than political ideology: subtle racial prejudice as a predictor of opposition to universal health care among US citizens . Journal of Social and Political Psychology 2016 ; 4 : 493 – 520 Crossref, Google Scholar

43. : Acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists and the implications for access to mental health care . JAMA Psychiatry 2014 ; 71 : 176 – 181 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. : Dimensions of institutional racism in psychiatry . Am J Psychiatry 1970 ; 127 : 787 – 793 Link, Google Scholar

45. : Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education . J Health Care Poor Underserved 1998 ; 9 : 117 – 125 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. : Structural competency: theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality . Soc Sci Med 2014 ; 103 : 126 – 133 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. : Long-term reduction in implicit race bias: a prejudice habit-breaking intervention . J Exp Soc Psychol 2012 ; 48 : 1267 – 1278 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. : Mental health inequities in the context of COVID-19 . JAMA Netw Open 2020 ; 3 : e2020104 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. : West India Emancipation (speech), August 3, 1857, https://rbscp.lib.rochester.edu/4398 Google Scholar