Dismantling Structural Racism in Academic Psychiatry to Achieve Workforce Diversity

The recruitment and retention of Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) faculty in academic medicine remains a challenge. Significant changes in the demographic landscape of the United States over the past decade highlight the need for medicine and health care systems to align better with the social and cultural needs of those seeking care. As we move forward, however, we must learn from earlier efforts if we are to be successful and achieve the desired outcome of a more diverse workforce.

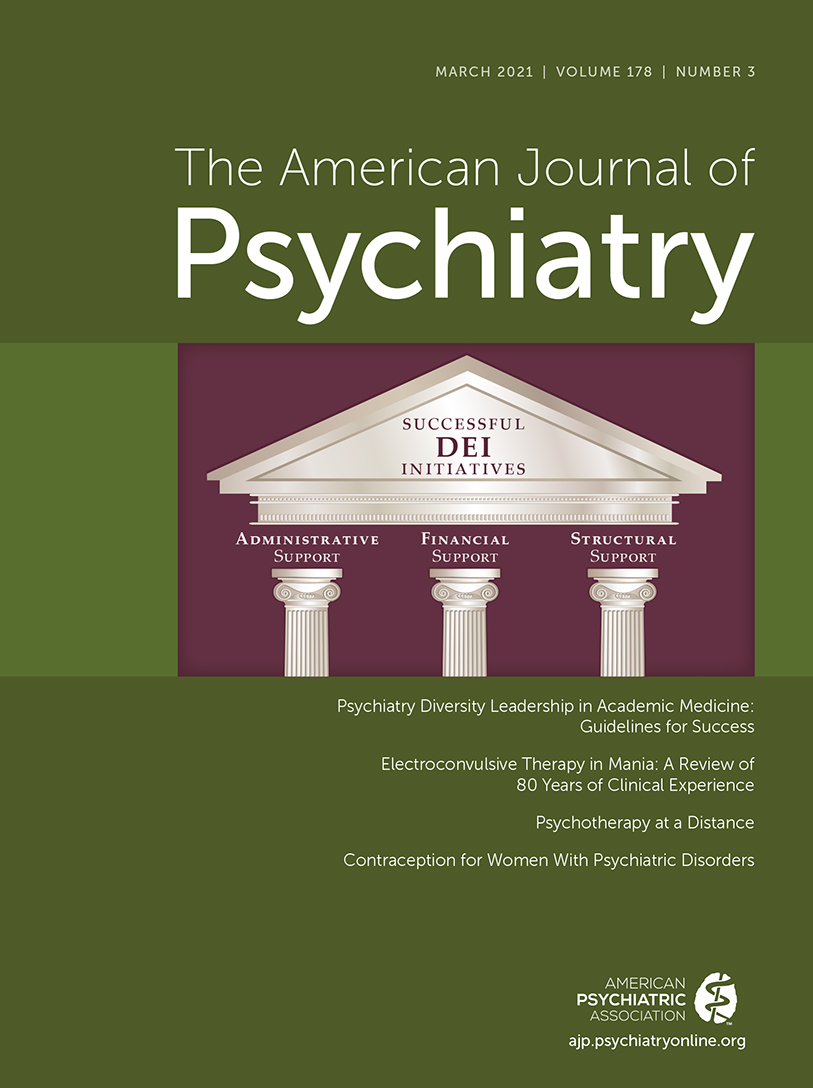

The article by Jordan et al. in this issue of the Journal (1) offers an important perspective on ways to increase diversity in academic psychiatry from a group of authors who represent the new face of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion faculty leaders in academic psychiatry. Their work offers insight on designing new models of faculty development to increase numbers of BIPOC individuals in academic psychiatry. The article identifies what leaders in academic psychiatry must do to manage challenges associated with recruiting, supporting, and sustaining diverse faculty across their three mission areas. Describing a range of experiences familiar to many BIPOC faculty in academic settings, the authors highlight the impact on both the individual and the institution, including the often unrealistic expectations of both. They also identify some of the hurdles that accompany each stage of the professional experience: recruitment and appointment to the position, the “doing the job” period, and concluding with the unfortunate professional and personal toll it takes on the individual, which frequently results in departure from the institution.

The 1910 Flexner Report (2) is a starting point for understanding the current challenges to workforce diversity. In a chapter devoted to medical education of African Americans, Abraham Flexner wrote, “The practice of the negro doctor will be limited to his own race, which in its turn will be cared for better by good negro physicians than by poor white ones.” In addition to the recommendations in the report designed to raise the quality of medical education in the United States, his recommendation to close seven of the nine historically Black medical schools, coupled with segregation practices of the time, resulted in a rapid decline in the available workforce to treat Black patients that continues today (3). It would be 50 years, and under provisions in the Civil Rights Act of 1964, before medical schools were desegregated (to receive federal funding for student financial aid and construction projects). During that same period, legislation creating Medicare and Medicaid offered an opportunity to increase diversity in the workforce, since medical centers had to desegregate to receive reimbursement for care (4). Unfortunately, this convergence of civil rights and health care policy did not create a more diverse workforce, prompting the development of affirmative action programs to increase minority enrollment in medical schools. The high point in that effort occurred in 1975, when enrollment of underrepresented minorities climbed from 3% to 10% nationwide, where it remained until the early 1990s (5).

In 1998 the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) charged its membership to begin concerted and systematic efforts to establish effective mentoring and faculty development programs to increase minority faculty. Then AAMC President Cohen stated in a JAMA editorial, “Racially and ethnically diverse faculty, fully empowered by the equitable presence of minorities within all ranks of the academy, is the only conceivable bridge to a diverse physician workforce” (6). Fifty years after passage of the Civil Rights Act, the Sullivan Commission on Diversity in the Healthcare Workforce offered policy recommendations to bring about systemic change to address the lack of diversity in the health professions (7). The report concluded that academic medical leaders were one of the most critical elements in any efforts to diversify the health professions workforce, and it would be their support for the agenda to change the culture and increase diversity that made the difference.

The article by Jordan et al. in this issue indicates that the same issues remain relevant today: increasing diversity in the health professions will require a major change in the culture in academic medicine and full examination of practices of their own institutions, and commitments to achieving this goal must be at the highest levels. The article also echoes the many first-person accounts being published online today of BIPOC academics working “inside” to transform the institutional culture to support more diverse and inclusive environments. Unfortunately, these accounts often serve as “departure” statements by individuals who have found their experiences to be unsatisfactory and traumatizing and are filled with words like “unheard, unsupported, and gaslighting,” “subcutaneous scars of racism and sexism,” and “minority tax” (8–11). Much like the case example in the article, institutional actions commonly do not offer the support needed to achieve higher-level faculty and leadership positions for these faculty members. Based on the relative lack of BIPOC senior leaders in academic medicine (e.g., president, chancellor, dean, and chair levels), many BIPOC faculty are assigned to work primarily in areas related to racial disparities in health care, leaving many to depart believing they will never be appreciated for the fullness of their abilities by their institution (12). And, as the article points out, for many who remain, there is often a lack of needed support to ensure their success, including equitable financial support and protected time for those academic endeavors that are part of the path to leadership.

The disadvantaged position in which minority faculty members find themselves compared with Whites developed through years of systematic segregation, discrimination, tradition, culture, and elitism in academic medicine (13). Many studies have identified reasons for the paucity of minorities pursuing careers in academic medicine (14–16). They include feelings of loneliness, isolation, and lower levels of career satisfaction, which remained consistent even when controlling for factors that typically influence promotions, such as years as a faculty member or measures of academic productivity. Lack of advancement is also attributed to spending more time on clinical than research activities, which means taking longer to achieve promotion or tenure. Peterson et al. (17) reported that underrepresented minority faculty were substantially more likely than Whites to perceive racial/ethnic bias in their academic career, resulting in lower career satisfaction scores. They wrote, “The high frequency of perceived racial/ethnic discrimination among minority faculty is concerning. Understanding the reasons for this and addressing the causes is both a moral and social issue for medical schools and teaching hospitals” (17). And for those who choose academia, there is a lack of mentors and role models. In the 1998 editorial in JAMA, Cohen stated, “As long as our medical school faculties have little more than token representation from many sectors of the richly diverse American culture, and as long as faculty advancement, for whatever reason, is grossly distorted by race and ethnicity, the medical profession cannot truly lay claim to the ethical and moral high ground it professes to occupy” (6).

History has proven that in medicine, systemic racism when left alone will produce the results it was designed to create (13). It is also clear that modifying medical/graduate medical education models and practices is not enough to produce the diverse mental health workforce needed for the 21st century. Once the entry-level challenges are overcome, there must be a focus on the lifelong learning required of clinical, research, and training faculty to improve diversity in academic psychiatry. To do otherwise is to abandon well-trained and social justice–motivated medical students and residents without the needed supports.

Moving forward, we cannot lull Black faculty into a false belief that a leader will support them when racism issues are raised, as often these individuals remain deafeningly silent, suggest the person is overly sensitive, or worse, gaslight them by suggesting that the person speaking out is the real problem. Recent personal accounts by Blacks of their experiences in academia suggest that this is a major factor in the departure of Black physicians (including psychiatrists) from academic medicine. To retain BIPOC faculty, institutional leadership must believe, validate, and act on faculty’s experiences of racism. Real change will require that no one be exempt in demonstrating the organization’s commitment to diversity and inclusion by creating the welcoming environments that will support institutionalization of this new culture (12). Finally, leaders in key positions must recognize some of the unintentional but well-institutionalized barriers in their systems and implement strategies that create more balanced, equitable, and welcoming environments for these individuals. The article in this issue of the Journal reports experiences in seven of the top 10 academic psychiatry departments across the United States. This suggests that with leadership and will, our top academic institutions are positioned to make the significant, sustained, and replicable changes needed to remove the barriers to achieving our goal of a more diverse workforce.

1 : Psychiatry diversity leadership in academic medicine: guidelines for success. Am J Psychiatry 2021; 178:224–228Link, Google Scholar

2 Flexner A: Medical Education in the United States and Canada: A Report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching (the Flexner Report). Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, Bulletin Number 4, 1910. http://archive.carnegiefoundation.org/publications/pdfs/elibrary/Carnegie_Flexner_Report.pdfGoogle Scholar

3 : Minorities in academic medicine: review of the literature. J Vasc Surg 2010; 51(suppl):53S–58SCrossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 : Entry of Black and other minority students into US medical schools: historical perspective and recent trends. N Engl J Med 1985; 313:933–940Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Association of American Medical Colleges: Minorities in medical education; facts and figures. Washington, DC, Association of American Medical Colleges, 2005Google Scholar

6 : Time to shatter the glass ceiling for minority faculty. JAMA 1998; 280:821–822Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Sullivan L: Missing Persons: Minorities in the Health Professions: A Report of the Sullivan Commission on Diversity in the Healthcare Workforce. 2004. https://drum.lib.umd.edu/bitstream/handle/1903/22267/Sullivan_Final_Report_000.pdfGoogle Scholar

8 Shim R: Structural racism is why I’m leaving organized psychiatry. STAT news, July 1, 2020. https://www.statnews.com/2020/07/01/structural-racism-is-why-im-leaving-organized-psychiatry/Google Scholar

9 Blackstock U: Why Black doctors like me are leaving academic medicine. STAT news, January 16, 2020. https://www.statnews.com/2020/01/16/black-doctors-leaving-faculty-positions-academic-medical-centers/Google Scholar

10 : Subcutaneous scars. Health Aff (Millwood) 2000; 19:164–169Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 : A piece of my mind: medical education and the minority tax. JAMA 2017; 317:1833–1834Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 : Diversity, equity, and inclusion that matter. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:

13 : The path forward: an antiracist approach to academic medicine. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:

14 : Perspective on professional socialization of women faculty. J Higher Educ 1986; 57:20–43Google Scholar

15 : Minority faculty and academic rank in medicine. JAMA 1998; 280:767–771Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 : Racial and ethnic disparities in faculty promotion in academic medicine. JAMA 2000; 284:1085–1092Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 : Faculty self-reported experience with racial and ethnic discrimination in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med 2004; 19:259–265Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar