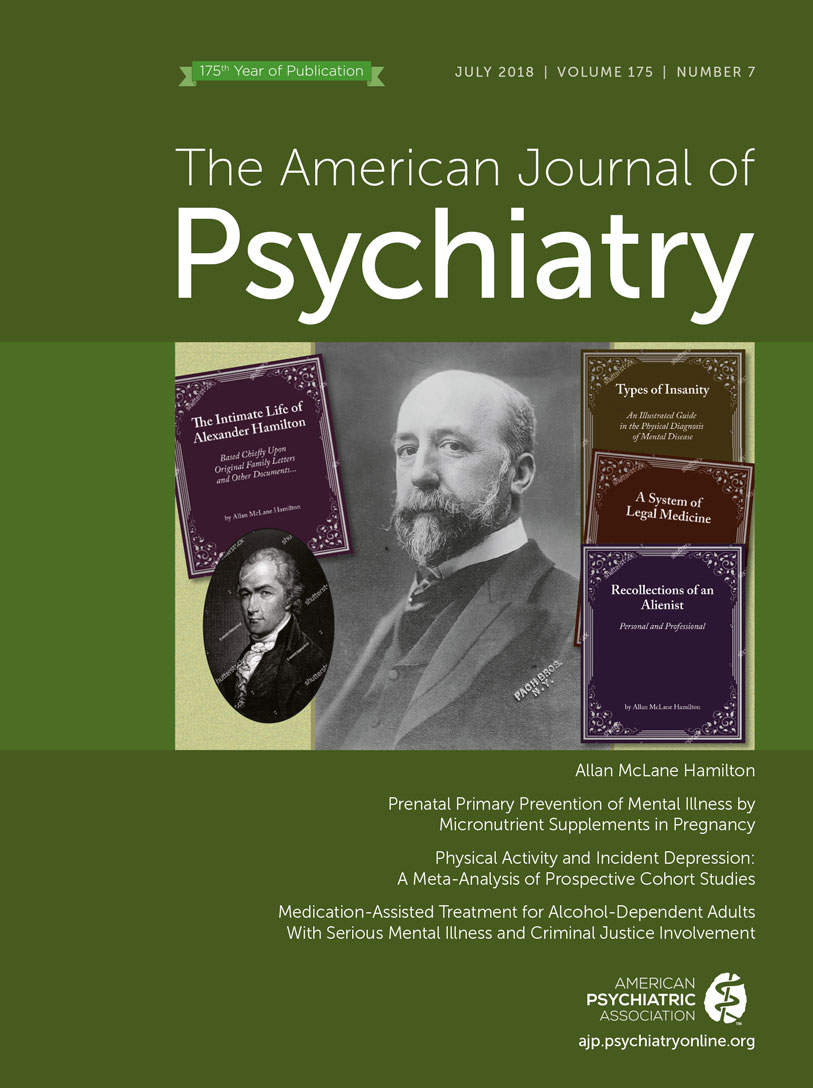

Allan McLane Hamilton

Allan McLane Hamilton. Library of Congress (image in the public domain).

Allan McLane Hamilton (1848–1919), a grandson of founding father Alexander Hamilton, became a prominent alienist (psychiatrist) in a career stretching from 1870 to his death in 1919. In the first part of his career, Hamilton specialized in neurology, including electrotherapeutics, epilepsy, and tremors, and he won first prize of the American Medical Association in 1879 for an essay on diseases of the spinal cord. He invented a gas cautery instrument and “the best dynamometer ever invented,” according to neurologist Charles Dana (1). Dana considered Hamilton to be the “last link to that group of men who gave distinction to American neurology.” In the second phase of his career, Hamilton branched out to medicolegal and psychiatric practice. He became known as the “dean of forensic psychiatry” and was an expert witness in many prominent trials (e.g., the trial of Charles Guiteau, the assassin of President James A. Garfield) and evaluations of well-known people, including Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of Christian Science. In her old age, Eddy was evaluated for mental competency by four experts, one of whom was Hamilton, who considered her to be competent.

As Dana said of Hamilton, he “enjoyed the spirit of contests.” He edited an encyclopedic System of Legal Medicine and authored Railway and Other Accidents: A Book for Court Use. In the second phase of his career, Hamilton wrote other books, including Mental Jurisprudence, Types of Insanity, and Nervous Diseases. Hamilton founded and became first president of the New York Psychiatric Society.

Dana observed in Hamilton a restlessness that went with “a temperamental character” and that interfered with Hamilton’s clinical practice. Hamilton spent many years in Europe, practiced in London, and was elected to Fellowship of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

The last phase of Hamilton’s professional life was accompanied by serious illness, which curtailed his clinical activities, and he turned his attention to writing, including The Drum (a book of poetry), the biography of his grandfather (1910) (2), and an engaging autobiography (1916).

Hamilton’s biography of his illustrious grandfather drew on many family documents and letters that were unavailable to others, and it also contained an interesting chapter on Alexander Hamilton’s personality, which the psychiatrically qualified Allan McLane Hamilton was well positioned to address. He notes his grandfather’s “nervous instability,” varying moods of alternating depression and “gaiety,” energy, and “resentful impatience,” disregard of caution, “mixture of aggressive force and infinite tenderness and amiability,” and his being “gentle and concerned for the happiness of others.” He includes documentation of a fierce ambition that was present from childhood, and the chapter enters into a discussion of whether or not a public figure with this constitution might be dangerous, as was thought to be the case by some of Hamilton’s political foes—but not by George Washington, who considered that such ambition was of the type that “prompts a man to excel in whatever he takes in hand.” Allan Hamilton refrained from any conclusion that his grandfather exhibited a pathology that would today be termed bipolar disorder, although Chernow (3) has hinted obliquely at this possibility in his description of Hamilton’s depressions, volatility, exuberance, and times of poor judgment. Allan Hamilton further noted that, in his psychiatric judgment, his grandfather shared with many geniuses the capacity for irresponsible behavior, as in the matter of his relationship with Maria Reynolds, the wife of James Reynolds and, for 2 years, the mistress of Alexander Hamilton.

It is of some interest that volatility and incaution were to be observed not only in Alexander Hamilton but also in Allan Hamilton’s son, who was twice court-martialed and was reprieved from dismissal only by the direct intervention of President Theodore Roosevelt. Allan himself, according to sources, seems to have demonstrated no more than mild bipolar spectrum elements, but they may not have been altogether absent.

1 : The career of Dr Allan McLane Hamilton. Med Rec 1920; 97:115–116Google Scholar

2 : The Intimate Life of Alexander Hamilton, Based Chiefly Upon Original Family Letters and Other Documents, Many of Which Have Never Been Published. New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1910Google Scholar

3 : Alexander Hamilton. New York, Penguin Books, 2005Google Scholar