Altering the Trajectory of Anxiety in At-Risk Young Children

Abstract

Objective:

Increasing evidence for the importance of several risk factors for anxiety disorders is beginning to point to the possibility of prevention. Early interventions targeting known risk for anxiety have rarely been evaluated. The authors evaluated the medium-term (3-year) effects of a parent-focused intervention for anxiety in inhibited preschool-age children.

Method:

The study was a randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention program provided to parents compared with a monitoring-only condition. Participants were 146 inhibited preschool-age children and their parents; data from two or more assessment points were available at 3 years for 121 children. Study inclusion was based on parent-reported screening plus laboratory-observed inhibition. The six-session group-based intervention included parenting skills, cognitive restructuring, and in vivo exposure. The main outcome measures were number and severity of anxiety disorders, anxiety symptoms, and extent of inhibition.

Results:

Children whose parents received the intervention showed lower frequency and severity of anxiety disorders and lower levels of anxiety symptoms according to maternal, paternal, and child report. Levels of inhibition did not differ significantly based on either parent report or laboratory observation.

Conclusions:

This brief, inexpensive intervention shows promise in potentially altering the trajectory of anxiety and related disorders in young inhibited children.

Internalizing problems such as anxiety and depression account for considerable public and personal burden across the lifespan. Developmentally, the common pattern is for anxiety to precede depression. Anxiety disorders are among the most common forms of mental disorder in early to middle childhood (1, 2), and depression shows a dramatic increase around middle adolescence (3, 4). Children and adolescents with anxiety disorders are at markedly elevated risk for the development of depression and other internalizing problems during adolescence and into early adulthood (5, 6).

Emerging evidence is beginning to identify several risk factors that may be involved in childhood anxiety (7). Twin studies point to a clear genetic risk in addition to contributions from shared and nonshared environmental factors (8). Although specific phenotypes have not been identified, some evidence has pointed to key roles for emotional reactivity and arousal as basic processes that may increase risk for later disorder (9, 10). These early characteristics are likely to increase risk for the emergence of certain temperaments that in turn predict later internalizing distress. Among the temperaments that have been most closely associated with anxiety disorders are a number of overlapping styles variously referred to as behavioral inhibition, social withdrawal, inhibition, and shyness (11–13). Longitudinal research has demonstrated that toddlers or young children showing high levels of these temperaments (which we refer to as inhibition in this article) are at increased risk for later internalizing distress and, more specifically, anxiety disorders (12, 14, 15).

Environmental risk for anxiety has been considerably more difficult to identify. A number of authors have argued for the importance of parental factors in childhood anxiety both through the influence of the parents' own anxiety and through parent-child interactions (16–18). Given the limited variance accounted for by shared environmental factors in anxiety disorders as well as the extensive evidence for the importance of the child's temperament, most theories emphasize the role of reciprocal processes reflected in temperament-environment correlations and interactions. It is generally believed that early inhibited behaviors in the child elicit overprotective and controlling parental behavior (often augmented by the parents' own anxiety), which enhances the child's inhibition across development, ultimately increasing risk for anxiety disorders (16, 17).

The elucidation of risk factors for anxiety disorders has begun to open prospects for early intervention and prevention of this high-frequency group of mental disorders (19, 20). Despite the high societal burden of anxiety disorders, few attempts have been made to develop selective prevention programs. Selective interventions are those that reduce the risk of a disorder by targeting known risk factors (21). It is possible that the dearth of such interventions is a result of the fact that models of environmental risk for anxiety have been developed only recently. One early trial failed to produce a significant reduction in temperamental inhibition after a 6-month intervention with preschool children and their parents, although the children's social competence and maternal control were successfully improved (22). Slightly more promising findings were reported in a later trial in which parents of highly inhibited young children received a six-session intervention to help reduce their child's anxiety (23). The intervention was designed to be brief and to be delivered in a group format to provide a minimally resource-intensive program with a real possibility for community application. Short-term effects at 12 months indicated that children of parents who received the intervention had slightly but significantly fewer anxiety disorders than children whose parents did not receive the intervention. These promising results provided the first indication that anxiety and other internalizing disorders might be preventable through early intervention.

Here we describe the medium-term results of this early intervention program. The sample has now been assessed 3 years after the end of the program, as the children begin to enter middle childhood.

Method

Participants

Participants for the study were 146 inhibited children 36 to 59 months old (mean age=46.5 months [SD=4.8]) and their parents. At 3 years, data from two or more assessment points were available for 121 children. Participants were recruited between June 1998 and June 2000, primarily through 5,609 screening packets that were distributed to parents across 95 preschools. A total of 1,647 (29.4%) packets were returned, and an additional 73 parents contacted the program following word of mouth. Mothers of all children (N=1,720) completed the screening questionnaire, the Short Temperament Scale for Children, an abbreviated version of the Childhood Temperament Questionnaire (Australian version) (24, 25). The approach subscale reflects social approach versus withdrawal, with higher scores reflecting greater withdrawal. Children who scored above 30 on the approach subscale (approximately 1.15 standard deviations above the age-adjusted norm) were invited in for further testing (N=285), and a total of 180 (63.2%) attended. All participants (mother and child) then engaged in a laboratory assessment for behavioral inhibition. The child was observed engaging in a series of tasks designed to elicit shy and inhibited behaviors. Tasks included interacting with a research assistant, interacting with a cloaked stranger, interacting with a same-age peer, and access to a novel toy; children were scored on the total time spent talking, time spent within arm's length of the mother, duration of staring at the peer, and frequency of approach to the stranger and the peer (11, 23, 26). Children who scored above predetermined cutoffs on three of these five behaviors were defined as behaviorally inhibited and eligible for the study; further details are provided in our previous report (23). Only children who scored above 30 on the Short Temperament Scale for Children and who met criteria for behavioral inhibition on laboratory assessment were included in the study (N=148, 82.2%); two families changed their minds and declined to participate in the program prior to randomization.

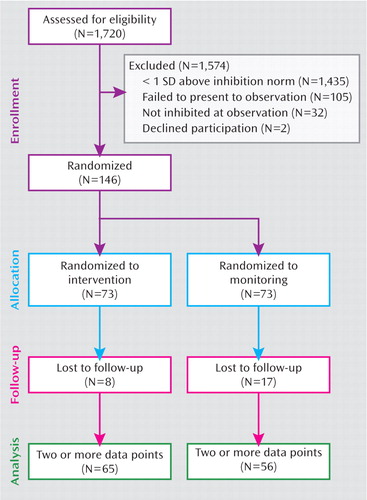

The remaining children (N=146) were randomly allocated to either a parent intervention group (N=73) or a monitor group (N=73) based on a coin toss. The final sample for this analysis constituted children who completed assessments at both baseline and at least one other assessment period (N=121, 82.9%). A significantly greater proportion of participants in the intervention returned data at two or more points (N=65, 89%) than participants in the monitoring condition (N=56, 77%) (χ2=3.91, df=1, p=0.048). Compared with participants who provided data at two or more assessment points, those who failed to do so and hence were lost to the study did not differ significantly at baseline on any demographic, temperament, or clinical variable aside from gender; children whose parents failed to provide data on more than one occasion were more likely to be male (64.0% compared with 41.3%; χ2=4.30, df=1, p=0.038). The participant flow through the study is depicted in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1. Participant Flow in a Randomized Controlled Trial of a Parent-Focused Early Intervention for Anxiety in Children

Outcome Measures

Diagnostic interview.

The Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children and Parents IV-Parent Version (27) was used to interview mothers of the children about their child's anxiety. Interviews were conducted by psychologists who were blind to group membership and were trained in the instrument by the first author. In keeping with DSM criteria, anxiety diagnoses were made only if the mother reported significant life interference for her child as a result of the reported symptoms. Interference was interpreted in keeping with the age—that is, relative to opportunities that might be expected in the absence of the symptoms. A second clinician scored 21% of the interviews from audiotape. Interrater agreement (kappa) for anxiety diagnoses was good, ranging from 0.77 to 0.86. Similarly strong interrater reliability of anxiety diagnoses in preschool-age children was reported in another study (28).

Two outcome measures are produced by the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children and Parents IV–Parent Version: presence or absence of a disorder and a clinical severity rating of the disorder. The clinical severity rating is made by the clinician on a 0–8 scale to reflect both the intensity of the symptoms and associated life interference. A severity score of 4 or greater is required to assign a diagnosis to a set of symptoms. At follow-up assessments all anxiety disorders were coded for clinical severity, and those for which the child had met diagnostic criteria at baseline were included in the total severity score. Our sample included 82% with social phobia, 18% with generalized anxiety disorder, 38% with separation anxiety disorder, 54% with specific phobias, 3% with other anxiety disorders, and 45% with other psychiatric disorders (including selective mutism, oppositional disorder, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder).

Anxiety symptoms.

A continuous measure of anxiety symptoms was based on the preschool version of the Spence Children's Anxiety Scale (29). Given the ages of the children in the early phases of the trial, only mothers completed this measure in reference to their child's anxiety symptoms. At the final assessment, when children were around 7 years old, the regular version of the Spence Children's Anxiety Scale (30) was used instead of the pre-school version. To allow comparison between these disparate versions, scores across the sample at each time point were standardized. At the final assessment point, we felt that the children were old enough to provide data on their own experience of anxiety symptoms, so at that time children also completed the self-report version of the Spence Children's Anxiety Scale.

Temperament.

To provide a continuous measure of reported child inhibition, both parents completed the Temperament Assessment Battery for Children–Revised (31). This instrument includes five subscales of temperament, and the social inhibition subscale was used as an outcome measure.

The laboratory observation that was used to determine inhibition status at baseline was also repeated at 12 and 24 months. As described above, the child was observed under several conditions. Measures used included total time spent talking, time spent referring to the mother, number of approaches to the peer and masked stranger, and time spent smiling. We converted these measures to standard scores and summed them to create a measure of observed inhibition. To allow for child maturation across time, the laboratory assessment was slightly modified at each assessment point. Hence to compare across time, these summed standard scores were also standardized.

Treatments

Parent intervention program.

The intervention provided to parents was conducted in groups of around six sets of parents. Both fathers and mothers were urged to attend, although mothers were most likely to attend. The program consisted of six 90-minute sessions; the first four were held weekly, the fifth was 2 weeks after that, and the final session was 1 month after that. Sessions were conducted by clinical psychologists with experience in running treatments for anxious children.

Session 1 began with a discussion of the nature of anxiety and its development, with the aim of increasing motivation among parents for the intervention. Session 2 covered basic principles of parent management techniques and especially the important effect of overprotection in maintaining anxiety. Sessions 3 to 5 covered the principles and application of exposure hierarchies as well as the application of cognitive restructuring to the parents' own worries. In session 6, continued application was discussed together with the importance of high-risk periods, such as the commencement of school. Parents were also encouraged to begin to apply cognitive techniques to their child as he or she matured. (More details are presented in the data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article.)

Monitoring-only condition.

Parents in the monitoring-only condition did not receive any intervention and were simply contacted for follow-up assessments. They were told that we had no information at this stage on whether the program would be effective, and hence we would monitor their child at yearly intervals to determine whether intervention was necessary. If required, children were eligible for enrollment in our standard child anxiety program once they reached age 7.

Procedure

Mothers whose child scored above 30 on the Short Temperament Scale for Children made appointments for attendance at the laboratory assessment and diagnostic interviews. Parents were informed of the random allocation requirement at first telephone contact, but randomization to conditions occurred only after the completion of baseline assessments. Diagnostic interviews and questionnaire measures (aside from child self-report) were repeated at 12, 24, and 36 months. Because of restricted resources, laboratory observations were repeated only at 12 and 24 months. All procedures were approved by the Macquarie University Human Research Ethics Committee, and parents provided written informed consent after receiving a complete description of the study.

Statistical Analysis

Variables assessed across the four assessment points (three for laboratory observations) were analyzed with mixed-model analyses using SPSS, version 17.0 (SPSS, Chicago). Analyses were based on completer data, and hence missing data were not imputed. However, an advantage of mixed models is that they can better handle missing data by not excluding participants on a casewise basis. All analyses compared the two groups over time; hence the principal interest was in the group-by-time interactions. Significant interactions were followed by post hoc estimates of fixed effects with baseline assessment as the reference point. The difference between the groups on the child's self-reported anxiety symptoms was only collected at 36 months and hence was compared using a t test.

Results

The two groups that constituted the final sample did not differ significantly on any of the assessed demographic baseline measures, including the child's age and gender; the parents' ages, country of birth, and education level; and the number of children in the family. Descriptive sample data are presented in Table 1. There were also no significant differences on baseline clinical measures, such as anxiety symptoms, inhibition, and number of disorders.

| Characteristic | Intervention Group (N=65) | Monitoring-Only Group (N=56) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Child's age (months) | 47.2 | 5.1 | 45.7 | 4.3 |

| Number of children in family | 2.1 | 0.6 | 2.1 | 0.6 |

| Mother's age (years) | 34.9 | 5.4 | 34.9 | 4.4 |

| Father's age (years) | 38.1 | 5.1 | 36.9 | 4.7 |

| N | % | N | % | |

| Female | 40 | 61.5 | 31 | 55.4 |

| Mother's education | ||||

| Did not complete high school | 5 | 7.7 | 5 | 8.9 |

| At least some university | 28 | 43.0 | 36 | 64.3 |

| Father's education | ||||

| Did not complete high school | 8 | 12.3 | 7 | 12.5 |

| At least some university | 28 | 47.1 | 32 | 57.1 |

| Mother's ethnicity | ||||

| Anglo-Saxon | 40 | 74.1 | 36 | 67.9 |

| Other European | 10 | 18.5 | 4 | 7.6 |

| Chinese | 2 | 3.7 | 7 | 13.2 |

| Father's ethnicity | ||||

| Anglo-Saxon | 47 | 83.9 | 38 | 71.7 |

| Other European | 6 | 10.7 | 6 | 11.3 |

| Chinese | 2 | 3.6 | 7 | 13.2 |

TABLE 1. Baseline Demographic Characteristics of Participants in a Randomized Controlled Trial of a Parent-Focused Early Intervention for Anxiety in Children

Diagnoses

Mixed-model analysis comparing the total number of anxiety disorder diagnoses across time between groups showed a significant main effect of time (F=44.45, df=3, 270.5, p<0.001) but no significant main effect of group. Notably, the group-by-time interaction was significant (F=2.97, df=3, 270.5, p=0.032). Follow-up comparisons of the interaction contrasts indicated a significant group-by-time effect from baseline to 12 months (t=2.16, df=254.3, p=0.032), from baseline to 24 months (t=2.22, df=272.8, p=0.027), and from baseline to 36 months (t=2.55, df=279.3, p=0.011). Estimated marginal means and standard deviations are presented in Table 2. To provide a more clinically relevant indication, Table S1 in the online data supplement shows the percentage of children in each group who met criteria for the main anxiety disorders across time.

| Measure | Intervention Group | Monitoring-Only Group | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (N=65) | 12 months (N=65) | 24 months (N=45) | 36 months (N=40) | Baseline (N=56) | 12 months (N=54) | 24 months (N=38) | 36 months (N=36) | |||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Number of anxiety diagnoses | 2.06 | 0.97 | 0.79 | 0.97 | 0.63 | 1.01 | 0.57 | 1.01 | 1.84 | 0.97 | 1.05 | 1.03 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 1.03 | 1.02 |

| Clinician-rated severity of anxiety diagnosesa | 5.72 | 3.22 | 2.42 | 3.22 | 2.09 | 3.29 | 2.70 | 3.29 | 5.10 | 3.29 | 3.03 | 3.31 | 4.88 | 3.27 | 4.19 | 3.42 |

| Child anxiety symptoms, based on maternal reportb (standard scores) | 0.06 | 1.05 | 0.08 | 1.05 | 0.00 | 1.01 | −0.14 | 0.95 | −0.05 | 1.05 | −0.11 | 1.03 | 0.14 | 0.99 | 0.32 | 0.96 |

| Child anxiety symptoms, based on self-reportb | 35.03 | 11.55 | 40.65 | 11.21 | ||||||||||||

| Maternal report of child inhibitionc | 48.32 | 7.74 | 38.70 | 7.82 | 34.35 | 7.85 | 33.75 | 7.91 | 46.31 | 8.08 | 38.92 | 7.86 | 35.94 | 8.14 | 35.55 | 7.98 |

| Paternal report of child inhibitionc | 43.80 | 8.38 | 39.70 | 9.11 | 34.07 | 8.99 | 33.86 | 9.30 | 42.07 | 8.91 | 37.72 | 9.26 | 33.81 | 8.87 | 34.77 | 8.88 |

| Laboratory-observed inhibition (standard scores) | −0.01 | 0.73 | 0.16 | 0.64 | 0.07 | 0.47 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 0.03 | 0.73 | 0.01 | 0.49 | ||||

TABLE 2. Estimated Marginal Means on Outcome Measures Across the Four Assessment Points in a Randomized Controlled Trial of a Parent-Focused Early Intervention for Anxiety in Children

A similar analysis examining the average clinical severity of anxiety disorders indicated a significant main effect of time (F=16.06, df=3, 294.4, p<0.001) and a significant main effect of group (F=8.07, df=1, 121.7, p=0.005), which were qualified by a significant group-by-time interaction (F=5.17, df=3, 294.4, p=0.002). Follow-up comparisons indicated no significant group-by-time interaction contrast from baseline to 12 months but a significant group-by-time contrast from baseline to 24 months (t=3.83, df=297.3, p<0.001) and from baseline to 36 months (t=2.24, df=305.2, p=0.026).

Anxiety Symptoms

Mixed-model analyses comparing the groups over time on the mothers' reports of anxiety symptoms failed to demonstrate a significant main effect for group, although there was a significant group-by-time interaction (F=3.65, df=3, 246.5, p=0.013; the main effect for time was not relevant since scores were converted to standard scores at each assessment point). Follow-up comparisons indicated no significant group-by-time interaction contrast from baseline to 12 months, nor from baseline to 24 months, but a significant group-by-time effect from baseline to 36 months (t=2.66, df=247.9, p=0.008). To provide a more interpretable indication of the scores, nonstandardized scores are reported in Table S2 in the online data supplement.

Children's self-reports of anxiety symptoms on the Spence Children's Anxiety Scale at 36 months showed lower levels of reported anxiety symptoms in the intervention group relative to the monitoring group, although the difference fell short of statistical significance (t=1.99, df=63, p=0.051).

Temperament

Comparison of mothers' reports of the child's inhibition showed a significant main effect reduction over time (F=78.42, df=3, 272.1, p<0.001), but neither the group main effect nor the group-by-time interaction was significant. Similarly, fathers' reports of their child's inhibition showed a significant main effect reduction over time (F=34.20, df=3, 223.6, p<0.001), but neither the group main effect nor the group-by-time interaction was significant.

Comparison of total observed inhibition based on the laboratory observations failed to show a significant main effect of group or group-by-time interaction (the main effect for time was not relevant since scores were converted to standard scores at each assessment point).

Discussion

By the time they reached middle childhood, at-risk children whose parents had received a brief intervention when the children were at preschool age were significantly less likely to display anxiety disorders or report symptoms of anxiety than similar children whose parents had not received the intervention. These data constitute the first evidence that it is possible to produce lasting changes in children's anxiety symptoms after a simple intervention early in the child's life. The fact that the intervention was brief and conducted across groups of parents makes the results especially impressive. The format of the program is such that it allows relatively low-cost delivery in a variety of community settings, including preschools, parent-child centers, and health clinics. As a result, these data suggest that the program holds major public health implications.

The precise components or mechanisms of the program responsible for the effects are not known. The program was developed on the basis of models that point to key factors in the development of anxiety disorders, including inhibited temperament, parent anxiety, and parent over-protection (17, 32). Interestingly, one of the key risk factors, the child's inhibition, was not specifically influenced by the intervention, although marked reductions were demonstrated in both groups. We previously showed that a slightly more intensive program applied with higher-risk children can produce reductions in inhibited temperament (28), perhaps suggesting that the lack of effects in the present study were due to the reductions reported in the monitoring-only group. Nevertheless, we were unable to demonstrate differences between groups in this study, and therefore it does not appear that the preventive effects of this program are mediated through reductions in inhibition. Theoretically it has been suggested that one of the key distinctions between an inhibited temperament and anxiety disorder is the life interference associated with disorder (33). In the present study we did not include a measure of life interference aside from the similar rating of clinical severity, which showed a clear reduction over time. However, in a later study, life interference from symptoms was shown to demonstrate marked reductions after a similar parent intervention (28). Clearly, both theory and refinement of prevention programs would benefit from greater understanding of the mechanisms responsible for these effects.

The nature of the assessment of inhibition was focused primarily on social fears. In line with this bias, the majority of children met criteria for social phobia. The effects of the intervention also appeared strongest for social phobia and, to a lesser extent, generalized anxiety disorder. Little difference between groups was noted on separation anxiety or specific phobias, although this might be due to marked natural reductions over time on these disorders in this population. Future research might evaluate intervention effects on children selected on the basis of a more even balance of social and physical threat concerns.

It has been suggested that inhibited children head along a life trajectory of increasing risk for development of anxiety and related disorders (19, 34). Genetic risk contributes to temperamental risk, which correlates and interacts with a variety of other risk factors, including parenting styles, parent psychopathology, peer interactions, and negative life events (17, 34, 35). Consequently, it has been suggested that reducing risk to even a relatively small degree early in life may set the child on a new trajectory of reduced risk (19). Despite the fact that it is unclear which risk factors were altered in the present study, the data are consistent with a picture of an altered trajectory. Differences between conditions were only minimally apparent at 12 months and appeared to show slightly larger effects with each passing year. Hence intervening at this particularly early key developmental period appears to have allowed a gradually increasing benefit to emerge.

“Jack,” age 3 years 11 months, was referred to the research program by his parents, who were concerned about his difficulty interacting with people outside the immediate family and participating in new activities. Despite attending the same preschool for 6 months, Jack was unable to initiate or reciprocate play with other children and spoke only to his main teacher. He tended to watch rather than participate in group activities. Jack's parents had withdrawn him from group swimming classes because he cried if he thought anyone was looking at him. His parents also avoided most social engagements because Jack constantly clung to them and demanded to go home. Both parents described themselves as having been very shy as children and were keen for Jack to avoid this experience.

When Jack arrived at the laboratory for the behavioral inhibition assessment, he hid behind his mother when greeted and sat on his mother's lap rather than at the table with the assessor. He did not respond verbally to the assessor for over 30 minutes, and when he did, his speech was soft and monosyllabic and he avoided eye contact. He reacted fearfully in the cloaked stranger interaction and returned to his mother's lap. Jack did not approach the novel toy or interact with the other child in the peer interaction component.

Jack's assessment showed that he met all criteria for behavioral inhibition, and he also met DSM-IV criteria for social phobia. His parents were randomly allocated to the 6-week parent education program. In the program, Jack's parents were encouraged to reduce their overprotective parenting style by not allowing Jack to avoid situations that made him anxious, such as attending parties and new activities. They were also encouraged to give Jack the opportunity to speak for himself rather than answering for him. Jack's parents were assisted in developing a graded exposure hierarchy to previously feared situations. They began with reinforcing Jack's efforts to reply when familiar people greeted him and gradually worked up to helping him to join in small group activities.

At his final follow-up assessment, at age 6 years 10 months, Jack no longer met criteria for social phobia and was no longer as strongly inhibited. Jack's mother reported that he was still reserved when he first met unfamiliar people and that she would still describe him as “shy.” However, he was participating with confidence in most school and extracurricular activities and he had a small group of close friends.

At the final follow-up point in this study, children were still relatively young (around age 7), and hence the focus of the study was specifically on anxiety disorders, which are common in this age group (2). The diagnostic interviews also assessed other internalizing disorders, such as depression and eating disorders, but the frequency of these disorders at this age was too low to be relevant. It is expected that with further development, differences between conditions may start to be seen on some of these other disorders. In particular, possible benefits of the program on major depressive episodes may begin to be noticed by midadolescence (3, 4). If this occurs, it would add even more to the cost-benefit profile of the program, given the particularly high burden of depression (36).

Applied studies always have a number of caveats and limitations, and several in the present study deserve consideration. The study was small by public health standards, and selection of participants was by convenience rather than by stratified population sampling. Our highly promising results now require replication in a larger representative sample of the population. Replication of the effects in disadvantaged populations and nonwhite ethnic groups is also essential. One major difficulty of a population-representative selection method in this case lay in the use of laboratory observations as a selection method. However, less than 18% of children who met inclusion criteria according to their mothers' reports of inhibition were ultimately excluded after laboratory observation. Hence larger studies could rely on maternal report for selection of participants without greatly sacrificing specificity. Clearly, the use of maternal report rather than laboratory observation would have a far greater community application. A large proportion of the results were also heavily influenced by maternal report. The fact that the main outcome measure, diagnostic interview, was determined by clinicians provides some additional confidence in the data, but the most powerful demonstration is the fact that by 36 months, the children themselves were reporting somewhat reduced anxiety symptoms. Nevertheless, future studies would benefit by including teacher and peer reports of anxiousness.

Early intervention for the prevention of anxiety and other internalizing disorders has lagged behind trials of prevention for externalizing disorders and social competence (37, 38). Our data provide the first evidence that early intervention through parent education can provide a medium-term protection from anxiety disorders in middle childhood. The intervention is brief and relatively inexpensive, providing marked opportunities for use in the community. Whether these promising findings will translate to continued protection from anxiety later in the developmental trajectory and whether they can generalize to protection from related disorders remain exciting possibilities.

1. : The DSM-IV rates of child and adolescent disorders in Puerto Rico. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61:85–93Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. : Quebec Child Mental Health Survey: prevalence of DSM-III-R mental health disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1999; 40:375–384Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. : Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. J Abnorm Psychol 1998; 107:128–140Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. : Stable prediction of mood and anxiety disorders based on behavioral and emotional problems in childhood: a 14-year follow-up during childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:2116–2121Link, Google Scholar

5. : Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:837–844Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. : The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:56–64Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. : Anxiety disorders during childhood and adolescence: origins and treatment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2009; 5:311–341Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. : Genetic influences on anxiety in children: what we've learned and where we're heading. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2007; 10:199–212Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. : Continuity and discontinuity of behavioral inhibition and exuberance: psychophysiological and behavioral influences across the first four years of life. Child Dev 2001; 72:1–21Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. : Infant predictors of inhibited and uninhibited profiles. Psychol Science 1991; 2:40–44Crossref, Google Scholar

11. : Galen's Prophecy: Temperament in Human Nature. New York, Basic Books, 1994Google Scholar

12. : Does shy-inhibited temperament in childhood lead to anxiety problems in adolescence? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000; 39:461–468Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. : Social withdrawl, inhibition, and shyness in childhood: conceptual and definitional issues, in Social Withdrawal, Inhibition, and Shyness in Children. Edited by Rubin KHAsendorpf JB. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1993, pp 3–17Google Scholar

14. : Stable behavioral inhibition and its association with anxiety disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992; 31:103–111Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. : Adolescent social anxiety as an outcome of inhibited temperament in childhood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999; 38:1008–1015Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. : Social withdrawal in childhood, in Child Psychopathology, 2nd ed. Edited by Mash EJBarkley RA. New York, Guilford, 2003, pp 372–406Google Scholar

17. : From anxious temperament to disorder: an etiological model of generalized anxiety disorder, in Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Advances in Research and Practice. Edited by Heimberg RGTurk CLMennin DS. New York, Guilford, 2004, pp 51– 76Google Scholar

18. : Family issues in child anxiety: attachment, family functioning, parental rearing, and beliefs. Clin Psychol Rev 2006; 26:834–856Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. : The development and modification of temperamental risk for anxiety disorders: prevention of a lifetime of anxiety? Biol Psychiatry 2002; 52:947–957Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. : Prevention of childhood anxiety disorders. Clin Psychol Rev 2000; 20:509–531Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. : Reducing Risks for Mental Disorders: Frontiers for Preventive Intervention Research. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1994Google Scholar

22. : Preventive intervention as a means of clarifying direction of effects in socialization: anxious-withdrawn preschoolers case. Dev Psychopathol 1997; 9:551–564Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. : Prevention and early intervention of anxiety disorders in inhibited preschool children. J Consult Clin Psychol 2005; 73:488–497Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. : The structure of temperament from age 3 to 7 years: age, sex, and sociodemographic influences. Merrill-Palmer Q 1994; 40:233–252Google Scholar

25. : Temperament and Development. New York, Brunner/Mazel, 1977Google Scholar

26. : Inhibited and uninhibited types of children. Child Dev 1989; 60:838–845Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. : The Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children–IV (Child and Parent Versions). San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp, 1996Google Scholar

28. : A selective intervention program for inhibited preschool-aged children of parents with an anxiety disorder: effects on current anxiety disorders and temperament. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009; 48:602–609Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. : The structure of anxiety symptoms among preschoolers. Behav Res Ther 2001; 39:1293–1316Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. : A measure of anxiety symptoms among children. Behav Res Ther 1998; 36:545–566Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. : Toward a structure of preschool temperament: factor structure of the temperament assessment battery for children. J Pers 1994; 62:415–448Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. : The development of anxiety: the role of control in the early environment. Psychol Bull 1998; 124:3–21Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. : Conceptual relations between anxiety disorder and fearful temperament, in Social Anxiety in Childhood: Bridging Developmental and Clinical Perspectives. Edited by Gazelle HRubin KH. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 2010, pp 17–31Google Scholar

34. : Social withdrawal in childhood. Annu Rev Psychol 2009; 60:141–171Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. : Behavioral inhibition: linking biology and behavior within a developmental framework. Annu Rev Psychol 2005; 56:235–262Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. : The Global Burden of Disease: A Comprehensive Assessment of Mortality and Disability From Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors in 1990 and Projected to 2020. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1996Google Scholar

37. : Strengthening social and emotional competence in young children who are socioeconomically disadvantaged: preschool and kindergarten school-based curricula, in Social Competence of Young Children: Risk, Disability, and Intervention. Edited by Brown WHOdom SLMcConnell SR. Baltimore, Paul H Brookes Publishing, 2008, pp 185–203Google Scholar

38. : Preventive interventions with young children: building on the foundation of early intervention programs. Early Educ Dev 2004; 15:365–370Crossref, Google Scholar