In This Issue

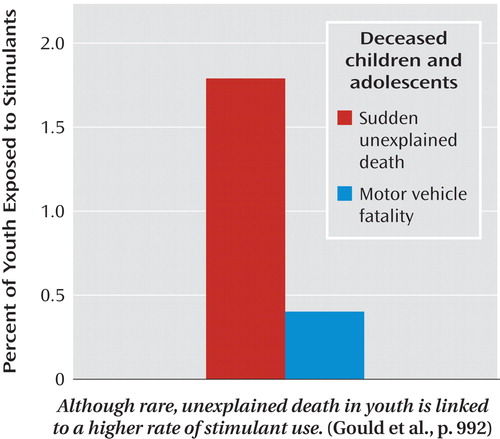

Stimulants and Sudden Death in Youth

A case-control study of deaths among children and adolescents indicated use of stimulant medications by 1.8% of the 564 youth whose sudden deaths were attributed to cardiac dysrhythmia or unknown causes, compared to 0.4% of matched youth who died as passengers in motor vehicle accidents. Gould et al. (CME, p. Original article: 992 ) identified sudden deaths in children and adolescents by examining state vital statistics from 1985 to 1996. Stimulant use was determined from informants, medical examiner records, and toxicology findings. Methylphenidate was the most common stimulant, and most were prescribed for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. In their editorial on p. Original article: 955 , Drs. Benedetto Vitiello and Kenneth Towbin note that stimulants are not innocuous but that sudden death is rare.

Depressed Adolescents in Primary Care: Long-Term Benefits of Short-Term Trial?

Primary care patients ages 13–21 in an intervention program designed to improve access to evidence-based treatment for depression recovered faster than patients who received enhanced treatment as usual. Asarnow et al. (p. Original article: 1002 ) found that the recovery rate was 90% at 18 months for both treatment conditions, but the rate at 6 months was 10% higher for the intervention group. The intervention group also had a lower rate of severe depression at 18 months, but this was due to a greater decline at 6 months. Patients receiving the intervention were more likely to receive psychotherapy or counseling, but not medication, in the first 6 months. Drs. John Campo and Jeffrey Bridge discuss adequate care for adolescents in an editorial on p. Original article: 961 .

Molecular Signature of Depression

Abnormalities in large-scale gene expression among deceased men with familial major depression were narrowed by finding which ones also occurred in mice subjected to unpredictable chronic mild stress. Sibille et al. (p. Original article: 1011 ) further restricted the list to the changes in 32 transcripts that were reversed by antidepressant treatment in mice. Although both the amygdala and anterior cingulate cortex are affected in major depression, cross-species abnormalities in gene expression were found only in the amygdala. These genes belong to an existing cohesive network and identify two distinct oligodendrocyte and neuronal phenotypes. Advances in analyzing gene expression are described by Dr. Simon Evans et al. in an editorial on p. Original article: 958 .

Synergism of Schizophrenia Risk Factors

The combination of prenatal infection and family history of psychosis—more than either factor alone—increased the risk of schizophrenia among offspring of 9,596 women in Helsinki. Clarke et al. (p. Original article: 1025 ) focused on women with upper urinary tract infections during pregnancy in 1947–1990 and compared the offspring from those pregnancies with siblings in the same family. Prenatal exposure to the infection did not increase the risk of schizophrenia, but the difference in risk between exposed and unexposed offspring with a family history of psychosis was five times as high as the difference between exposure groups without genetic vulnerability. Drs. Jim van Os and Bart Rutten describe gene-environment approaches in an editorial on p. Original article: 964 .

Addiction Related to Early Abuse/Neglect but not African Ancestry

Greater African genetic heritage was not related to a higher risk of substance dependence among 490 African Americans studied by Ducci et al. (CME, p. Original article: 1031 ). In fact, the degree of African ancestry was somewhat lower among African American patients with cocaine, opiate, or alcohol dependence than among African American comparison subjects. Substance dependence showed a large association with a childhood history of emotional, physical, or sexual abuse or emotional or physical neglect. African genetic heritage was not related to childhood abuse or neglect but was linked to living in an impoverished neighborhood. In an editorial on p. Original article: 967 , Dr. Robert Freedman examines these nature versus nurture issues.