Older Adults’ Attitudes Toward Enrollment of Non-competent Subjects Participating in Alzheimer’s Research

Abstract

Objective: Research that seeks to enroll noncompetent patients with Alzheimer’s disease without presenting any potential benefit to participants is the source of substantial ethical controversy. The authors used hypothetical Alzheimer’s disease studies that included either a blood draw or a blood draw and lumbar puncture to explore older persons’ attitudes on this question. Method: Face-to-face interviews were conducted with 538 persons age 65 and older. Questions explored participants’ understanding of research concepts, their views on enrolling persons with Alzheimer’s disease in research, and their preferences regarding having a proxy decision maker, granting advance consent, and granting their proxy leeway to override the participant’s decision. Additional questions assessed altruism, trust, value for research, and perceptions of Alzheimer’s disease. Results: The majority (83%) were willing to grant advance consent to a blood draw study, and nearly half (48%) to a blood draw plus lumbar puncture study. Most (96%) were willing to identify a proxy for research decision making, and most were willing to grant their proxy leeway over their advance consent: 81% for the blood draw study and 70% for the blood draw plus lumbar puncture study. Combining the preferences for advance consent and leeway, the proportion who would permit being enrolled in the blood draw and lumbar puncture studies, respectively, were 92% and 75%. Multivariate models showed that willingness to be enrolled in research was most strongly associated with a favorable attitude toward biomedical research. Conclusions: Older adults generally support enrolling noncompetent persons with Alzheimer’s disease into research that does not present a benefit to subjects. Willingness to grant their proxy leeway over advance consent and a favorable attitude about biomedical research substantially explain this willingness.

Dementia, especially dementia caused by Alzheimer’s disease, is among the most serious public health challenges of the coming decades. With the rapid aging of the U.S. population, within 50 years the number of people with dementia will reach 12 million (1) . For the health care community to respond to this challenge, research is needed that often requires the participation of subjects who themselves have dementia. Yet ethical norms in the protection of human subjects limit vulnerable persons’ participation in research that does not offer the prospect of direct medical benefit and presents more than minimal risks (2) .

To address this problem, researchers and ethicists have developed a model of proxy consent. Proxy consent allows another individual to provide consent for a subject who is not competent to do so. The ethic to guide proxy consent is a substituted judgment: a proxy should make the decision on the basis of what the patient, if capable, would choose (3) . This approach is advocated especially in research that presents more than minimal risks and does not offer a reasonable prospect of benefit to the subject. For this kind of research, proposed guidelines require that a noncompetent subject be enrolled only if he or she has executed a previous written directive indicating a willingness to participate in such research (4) .

Unfortunately, studies show only fair agreement between what a proxy thinks a patient would decide and what the patient actually decides (5 , 6) , and one study found that some proxies choose the opposite of what they believe the now noncompetent patient would have wanted (7) .

Yet little research has examined public views on this controversy. Studies suggest that adults may support the use of proxies for enrolling noncompetent persons with Alzheimer’s disease in research. Most important, people may be willing to grant their proxy discretion, or leeway, to decide what would be best, even if the proxy’s decision is opposed to what the person would have wanted (8 – 10) . However, these studies have focused on the views of persons already enrolled in research about protocols that have the potential to benefit participants.

No study has examined views of older adults on the degree of leeway they would give their proxy to enroll them in Alzheimer’s disease research that does not present a reasonable prospect of benefit to the study participants. Also, no study has verified that respondents understand core concepts about research, proxy decision making, and research risk. Hence, the available data may come from respondents who do not have an adequate understanding of the ethical issues involved (11) . These are complex concepts that can be especially difficult to convey because of the necessity that they be framed as hypothetical possibilities that might occur in the future. Finally, we do not know the characteristics of people who are willing or not willing to allow proxy consent for research that enrolls noncompetent subjects. This is especially important for populations who have historically suffered undue burden in research and therefore may mistrust research, such as African Americans (12) .

Until we better understand whether people are willing to participate in nonbeneficial research that enrolls persons with Alzheimer’s disease and why they are willing, policymakers cannot develop research ethics policies that respect the values of the people they are designed to protect and that will resolve the controversy that has caused some states and institutional review boards to limit substantially the practice of proxy consent for research (13 – 15) . This line of inquiry is especially important because the Office for Human Research Protections, the agency within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) that writes and enforces human subjects research protection regulations, has a working group engaged in determining whether regulations are needed for research that enrolls persons with impairments in their decisional capacity (16) .

The purpose of this study was to discover whether older adults support enrolling noncompetent persons with Alzheimer’s disease into research that does not benefit participants. We focused on persons age 65 and older because age is one of the chief risk factors for progressive cognitive impairment. We focused on Alzheimer’s disease because it is among the most common causes of late-life cognitive impairment, and we focused on biological markers of the disease in blood and spinal fluid because there is an urgent need to identify them. Our survey sought to determine whether older adults would want to be enrolled in nonbeneficial Alzheimer’s disease research studies if they themselves had Alzheimer’s disease and were unable to give informed consent. We also sought to identify the demographic and attitudinal characteristics of persons who would want to be enrolled in such studies.

Method

Participants

Eligible participants were residents of the southeastern Pennsylvania region who were at least 65 years old; understood spoken English; could read text in a 14-point font or, if visually impaired, could follow a verbal reading of survey text; and provided verbal informed consent. Participants were recruited from three clinics (the Philadelphia VA Medical Center, a university urban geriatrics practice, and a university suburban internal medicine practice) and a Philadelphia city senior center.

The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Pennsylvania and the Philadelphia VA Medical Center; in addition, we obtained letters of support from each recruitment site. After receiving a description of the study, participants provided verbal informed consent. Participants received a $20 gift certificate to compensate for time and effort.

Measures

We performed a cross-sectional, 45- to 60-minute face-to-face interview that included fixed-choice and open-ended questions. The interview consisted of three parts and incorporated periodic reviews of responses to ensure that participants understood the implications of their choices.

The first part of the interview assessed understanding of basic research concepts (the proxy role, making plans for the future, research, different kinds of benefits, and informed consent) by assessing comprehension of a story read to participants. The vignette describes a woman’s attitudes about research and how, at a later time, she develops Alzheimer’s disease and is recruited for a study; her husband becomes her proxy. To assess participants’ understanding and reasoning about the story’s core points, the interviewer asked a set of questions, such as “Can you tell me in your own words what is research?” and “Who can make the decision whether Mrs. Adams should join this research study?” These questions were based on our previous research using the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Treatment (17) to assess the decision-making ability of persons with Alzheimer’s disease, their caregivers (10 , 18 , 19) , and persons with serious illness (20 , 21) .

The second part was a survey of participants’ views about research that enrolls persons with Alzheimer’s disease. Only participants who showed adequate understanding of core concepts continued to part 2. At the beginning of part 2, they were asked if they would be willing to have a proxy for research decisions: “Suppose that in the future you had Alzheimer’s disease and you were unable to make decisions about joining a research study. Would you want someone else to serve in the role that Mr. Adams did and make decisions for you about enrolling in research?”

Next, they were presented one of two hypothetical studies on developing diagnostic tests for biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease: a minimal-risk study that involved a blood draw and a greater-than-minimal-risk study that involved a blood draw plus a lumbar puncture to draw spinal fluid; the studies were presented in random order. For each study, the interviewer verified that participants understood the risks and benefits of the study and then asked whether they would be willing to provide advance consent for such a study if they had Alzheimer’s disease: “Suppose that in the future, you had Alzheimer’s disease and you were in the physical and mental state Mrs. Adams was in. Would you say that you would want to participate or not want to participate?”

Participants who had designated a proxy were asked whether they would grant their proxy leeway to override the participant’s advance consent. The question was tailored to fit the participant’s preference for a proxy and their advance consent. The following is an example of a question asked of a participant who selected his daughter as proxy and was not willing to grant advance consent to the lumbar puncture: “How much leeway should your daughter have in overriding your choice and instead enroll you in the study? By ‘leeway’ I mean your daughter should exercise freedom to choose what she thinks is best rather than follow your instructions you just told me about. Would you say she should have no leeway or at least some leeway?” The implications of participants’ responses about willingness to grant leeway were reviewed with the participant, in particular that leeway could override their advance consent. Participants could then change answers, if desired.

Part 3 contained questions designed to measure relevant attitudes and to collect demographic information.

Altruism

We used the eight-item Social Responsibility Scale (22) (possible scores range from 8 to 40, with higher scores indicating a greater degree of social responsibility). We also used two single-item measures of behaviors plausibly associated with altruism related to science and health care: “Have you signed up to be an organ donor?” and “Have you signed up to donate your body to science?” We selected these two behaviors because they are topically related to the decision to be in research and they are readily reported and ascertained by family.

Trust

We used the 10-item Health Care System Distrust Scale (23) (possible scores range from 10 to 50, with higher scores indicating more trust).

Value for research

Attitudes about research were assessed using the Research Attitudes Questionnaire (24) , an 11-item measure that assesses how favorably or unfavorably one views biomedical research (possible scores range from 11 to 55, with higher scores indicating more favorable views).

Perception of Alzheimer’s disease

We used the Perceived Threat of Alzheimer’s Disease Scale (25) (possible scores range from 7 to 35, with higher scores indicating greater perceived threat) and a single-item measure of familiarity with Alzheimer’s disease: “Have you been or are you now close to someone who has Alzheimer’s disease?”

Social and demographic characteristics

We recorded participants’ age, gender, ethnicity, self-identified racial identity, highest grade of school, financial burden measured in terms of how finances work out at the end of the month (26) , number of living children, marital status, and history of working in medicine or science.

Data Analyses

The primary endpoint measure was whether participants indicated a willingness to participate in research that enrolled persons with Alzheimer’s disease who were not capable of consent under each of two research risk conditions. We operationalized this as the dichotomous variable “willing to participate.”

For each of the research conditions, we defined persons not willing to participate as those who indicated that they would not want a proxy for research and that they would not grant advance consent, or those who would want a proxy but would not grant advance consent and would not grant their proxy leeway over that advance directive. All other persons were defined as willing to participate, because the net effect of their preferences was willingness to be enrolled. For example, a person was classified as willing to participate if his or her advance consent for the greaterthan-minimal-risk spinal fluid sample study was “would not want to enroll” but that person had been willing to appoint a proxy and to grant the proxy leeway over this decision.

We used logistic regression to examine associations between participant characteristics and willingness to allow proxy consent for each research risk condition. The binary participation outcome for both high and low risk was analyzed in Stata, release 10 (Stata Corp., College Station, Tex.), using a logistic regression model estimated with generalized estimating equations (GEE) (27) . Accordingly, standard errors of effect estimates were obtained with the sandwich variance estimator to adjust for correlated high- and low-risk observations. We did not include order of scenario presentation in the models because it was not conceptually a confounder in the effects of interest with willingness to participate. Moreover, the interaction of order of presentation with scenario was not significant. Because some studies suggest that race and attitudes about research may influence willingness (12) , multivariate GEE models were used to evaluate whether self-reported minority status has an effect on willingness to enroll above and beyond other demographic and attitudinal covariates.

Scale scores missing less than 20% of items were prorated; missing items were assigned the average value of nonmissing items and added to the scale. Participants with any individual scale having greater than 20% missing items were not included.

Results

Participant Characteristics

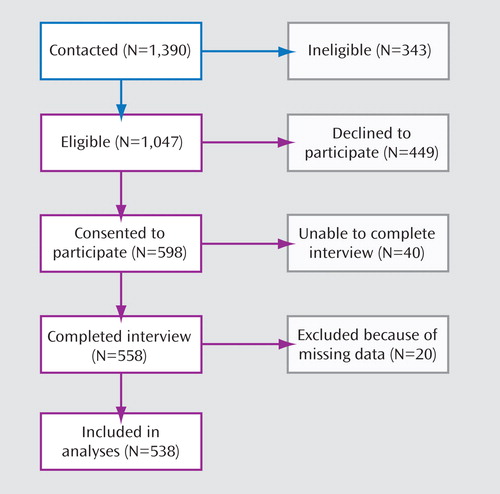

As shown in Figure 1 , 598 persons agreed to participate in an interview (57%). Women were more likely than men to participate (61% versus 53%, respectively, χ 2 =7.8, p=0.005). No differences were observed in the racial distribution of participants versus nonparticipants. Among participants, 93% passed the core concepts assessment. After exclusion of 20 participants who did not complete all covariate scales, the final sample consisted of 538 participants. There were no significant differences in outcome measures, attitudes, or demographic characteristics between the 20 excluded and the remaining participants. Data were collected from December 2005 to December 2007.

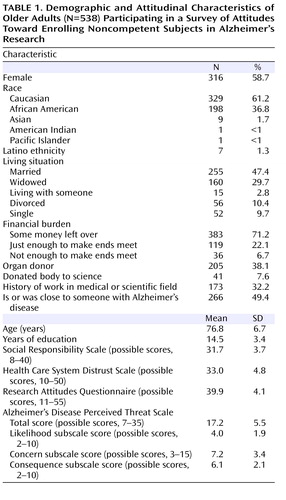

Table 1 summarizes participants’ demographic and attitudinal characteristics. One-third were African American, 59% were female, 38% had no more than 12 years of education, and more than one-quarter (29%) reported that they had either just enough or not enough money at the end of the month.

Willingness to Be Enrolled in Research Without Benefits to Participants

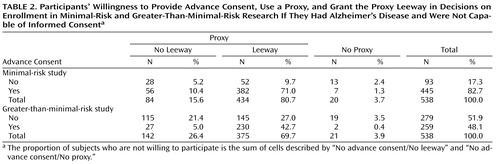

As shown in Table 2 , most participants (96%) were willing to designate a proxy for research decision making (one person wanted a proxy for the minimal-risk [blood draw] study but not for the greater-than-minimal-risk [lumbar puncture] study). The majority (83%) indicated willingness to grant advance consent to the blood draw study, and nearly half (48%) to the lumbar puncture study. For both research risk conditions, most persons were willing to grant leeway over advance consent: 81% for the blood draw study and 70% for the lumbar puncture study.

When preferences for providing advance consent were combined with those, in the case of persons who wanted a proxy, for granting leeway to the proxy, we found that 497 participants (92%) had preferences that would allow enrollment in the blood draw study and 404 (75%) in the lumbar puncture study.

Participants’ willingness to grant leeway over their advance consent to a proxy substantially contributed to their overall willingness. Without including participants’ decision to grant their proxy leeway over their advance consent, the proportion whose preferences suggest that they would be willing to be enrolled in the blood draw study would have decreased from 92% to 83%, and the proportion for the lumbar puncture study would have decreased from 75% to 52%.

Characteristics Associated With Supporting Participation in Research Without Benefits to Participants

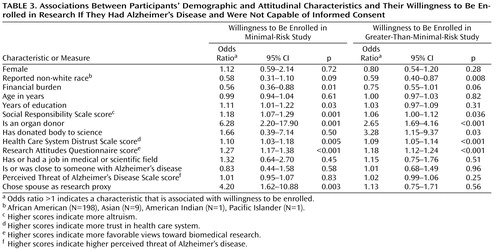

Table 3 shows that in both research risk conditions, willingness to be enrolled was associated with higher scores on the Social Responsibility Scale, trust in the health care system, and favorable attitudes about research. In addition, participants who self-reported behaviors associated with these attitudes were more willing to permit proxy consent for research that does not present a benefit—persons who reported they were organ donors and, in the case of greater-than-minimal-risk research, those who reported that they had donated their body to science.

We did not find a relationship between support for proxy consent and the perceived threat of Alzheimer’s disease, being close to someone with Alzheimer’s disease, or a history of working in the medical or scientific fields.

Demographic characteristics associated with willingness to be enrolled in research with proxy consent varied depending on the research risk condition. Persons who chose a spouse or partner as their research proxy, those who reported more years of education, and those who reported less financial burden were more willing to be enrolled in the minimal-risk research, but these associations were not seen in the greater-than-minimal-risk condition. Persons who reported being in a racial minority group were less willing to be enrolled in greater-than-minimal-risk research.

Multivariate analyses to examine the relative effects of attitudes and characteristics found that in the greater-than-minimal-risk scenario, minority status was the only demographic variable associated with a reduced willingness to participate. Other demographic measures (years of education, financial burden, and gender) did not attenuate this association (odds ratio=0.63, 95% CI=0.42–0.96, p=0.03). Minority status was not significant in the minimal-risk scenario, although the effect was in the same direction (odds ratio=0.58, 95% CI=0.31–1.10, p=0.09).

Similarly, favorable attitudes toward research constituted the only attitudinal characteristic associated with willingness to participate, and the addition of other attitudinal variables (Social Responsibility Scale score, Health Care System Distrust Scale score, and Perceived Threat of Alzheimer’s Disease Scale score) did not attenuate this effect in either the greater-than-minimal-risk (odds ratio=1.19, 95% CI=1.13–1.27, p<0.001) or the minimal-risk (odds ratio=1.19, 95% CI=1.13–1.27, p<0.001) scenario.

Models examining the combined effect of Research Attitudes Questionnaire score and minority status for the greater-than-minimal-risk scenario showed the effect for minority status disappearing (Research Attitudes Questionnaire score: odds ratio=1.20, 95% CI=1.14–1.26, p<0.001; minority status: odds ratio=0.84, 95% CI=0.55–1.28, p=0.42).

Discussion

Our results suggest that a majority of older adults support enrollment of noncompetent patients with Alzheimer’s disease in research that will not directly benefit participants. Even in the greater-than-minimal-risk lumbar puncture scenario, three-quarters of participants had preferences permitting their enrollment in research if they had Alzheimer’s disease and could not provide informed consent. We discuss four key findings.

It is notable that willingness to grant a proxy leeway over advance consent substantially contributed to overall willingness to be enrolled. These results suggest that many people who do not want to participate in certain kinds of medical research are nonetheless willing to appoint a proxy with the ability to override that decision. This result is supported by a study of persons with Alzheimer’s disease (8) showing that preferences about granting proxy leeway over an advance consent decision are a critical element of how elderly people formulate advance planning preferences.

The second key finding is that favorable attitudes toward research, a sense of social responsibility, and trust in the health care system were associated with support for proxy consent, but experiences with Alzheimer’s disease were not. This result expands the finding from a postal survey of elderly persons that the strongest association with support for proxy consent for research was favorable attitudes toward research (24) . Neither that study nor a telephone survey of caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease (9) found that attitudes about Alzheimer’s disease were associated with support for proxy consent. Collectively, these findings suggest that overarching values such as trust and altruism shape attitudes about the ethics of research in which noncompetent subjects are enrolled, not specific views about the disease under study.

Third, persons who reported being in a racial minority were less likely to support enrolling noncompetent persons in greater-than-minimal-risk research. Notably, this association was independent of age, education, and financial burden yet dropped out of models that adjusted for attitudes about research. These results suggest that favorable attitudes about research, more so than trust or altruism, largely explain racial differences in support for enrolling noncompetent subjects in research.

Finally, most participants (93%) generally understood the core concepts of the proxy role, making plans for the future, research, different kinds of benefits in research, and informed consent. This finding is encouraging. It suggests that most older adults can participate in research advance planning.

The strengths of this study are that all respondents demonstrated adequate understanding of the core concepts required for informed research participation, and the interview was designed to ensure that participants understood the implications of their preferences. Previous research in advance planning has been limited by a failure to ensure that participants understood the complex, future-oriented issues at stake (11) . Second, the sample reflected the ethnic diversity of the Philadelphia region, and we measured attitudes including trust, altruism, value for research, and perceptions of Alzheimer’s disease. This allowed us to identify demographic and attitudinal characteristics associated with preferences about proxy consent.

Limitations include the focus on research to develop biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease; our results may not apply to research involving other kinds of conditions, such as critical illness. In addition, our sample was limited to persons at plausible risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease: persons age 65 and older. While this design choice was consonant with the need for a real-world scenario in the study, it excludes the views younger cohorts might have on proxy consent, which may be different. Future studies should investigate views of persons at risk for critical illness and younger persons.

Research that seeks to enroll noncompetent persons with proxy consent, especially greater-than-minimal-risk research, is a source of substantial controversy. Some states and institutions restrict the practice (28) ; federal research regulations offer no guidance on the matter; and past efforts to develop guidance have collapsed (4 , 29) . As noted earlier, a working group at DHHS’s Office of Human Research Protections is engaged in determining whether regulations are needed for research that enrolls persons with impairments in decision-making capacity (16) . Our results have important implications for that effort. They suggest that, in general, elderly people support enrollment of noncompetent patients in research on the patients’ disease even if that research will not benefit the study participants’ health and well-being but might benefit others instead. This support reflects a willingness to grant a proxy leeway over an advance consent. Hence, policies that require a proxy to exercise a strict substituted judgment based on past consent preference do not necessarily respect how people want their proxies to make decisions. Our results also suggest that researchers and their funders should focus on how their behaviors shape people’s attitudes about research.

1. Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Bienias JL, Bennett DA, Evans DA: Alzheimer disease in the US population: prevalence estimates using the 2000 census. Arch Neurol 2003; 60:1119–1122Google Scholar

2. US Department of Health and Human Services: Federal policy for the protection of human subjects: notices and rules. Federal Register 1991; 56:28003–28032Google Scholar

3. Buchanan AE, Brock DW: Deciding for Others: The Ethics of Surrogate Decision Making. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1989Google Scholar

4. National Bioethics Advisory Commission: Moving ahead in research involving persons with mental disorders: summary and recommendations, in Research Involving Persons With Mental Disorders That May Affect Decisionmaking Capacity, vol 1. Rockville, Md: National Bioethics Advisory Commission, 1998, pp 51–67Google Scholar

5. Sachs GA, Stocking CB, Stern R, Cox DM, Hougham G, Sachs RS: Ethical aspects of dementia research: informed consent and proxy consent. Clin Res 1994; 42:403–412Google Scholar

6. Coppolino M, Ackerson L: Do surrogate decision makers provide accurate consent for intensive care research? Chest 2001; 119:603–612Google Scholar

7. Warren JW, Sobal J, Tenney JH, Hoopes JM, Damron D, Levenson S, DeForge BR, Muncie HL Jr: Informed consent by proxy: an issue in research with elderly patients. N Engl J Med 1986; 315:1124–1128Google Scholar

8. Stocking CB, Hougham GW, Danner DD, Patterson MB, Whitehouse PJ, Sachs GA: Speaking of research advance directives: planning for future research participation. Neurology 2006; 66:1361–1366Google Scholar

9. Wendler D, Martinez RA, Fairclough D, Sunderland T, Emanuel E: Views of potential subjects toward proposed regulations for clinical research with adults unable to consent. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:585–591Google Scholar

10. Karlawish J, Kim SY, Knopman D, van Dyck CH, James BD, Marson D: The views of Alzheimer disease patients and their study partners on proxy consent for clinical trial enrollment. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2008; 16:240–247Google Scholar

11. Miles SH, Koepp R, Weber EP: Advance end-of-life treatment planning: a research review. Arch Intern Med 1996; 156:1062–1068Google Scholar

12. Shavers V, Lynch C, Burmeister L: Racial differences in factors that influence the willingness to participate in medical research studies. Ann Epidemiol 2002; 12:248–256Google Scholar

13. US Department of Health and Human Services, Office for Human Research Protections: Letter from the Division of Compliance Oversight to the Vice Dean for Research, Thomas Jefferson University, “Re: Human Research Protections Under Multiple Project Assurance (MPA) M-115,” June 10, 2002; available at http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/detrm_letrs/YR02/jun02a.pdfGoogle Scholar

14. US Department of Health and Human Services, Office for Human Research Protections: Letter from the Division of Compliance Oversight to the Vice Provost for Research, University of Washington, “Re: Human Research Subject Protections Under Multiple Project Assurance (MPA) M-1183,” July 31, 2002; available at http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/detrm_letrs/YR02/jul02p.pdfGoogle Scholar

15. Kim SY, Karlawish JH: Ethics and politics of research involving subjects with impaired decision-making abilities. Neurology 2003; 61:1645–1666Google Scholar

16. Department of Health and Human Services, Working Group on the National Bioethics Advisory Commission Report: Analysis and proposed actions regarding the NBAC report: “Research Involving Persons With Mental Disorders That May Affect Decisionmaking Capacity.” http://aspe.hhs.gov/sp/nbac/index.shtmlGoogle Scholar

17. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS, Hill-Fotouhi C: The MacCAT-T: a clinical tool to assess patients’ capacities to make treatment decisions. Psychiatr Serv 1997; 48:1415–1419Google Scholar

18. Karlawish JH, Casarett DJ, James BD: Alzheimer’s disease patients’ and caregivers’ capacity, competency, and reasons to enroll in an early-phase Alzheimer’s disease clinical trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002; 50:2019–2024Google Scholar

19. Karlawish JH, Casarett DJ, James BD, Xie SX, Kim SY: The ability of persons with Alzheimer disease (AD) to make a decision about taking an AD treatment. Neurology 2005; 64:1514–1519Google Scholar

20. Casarett DJ, Karlawish JH, Hirschman KB: Identifying ambulatory cancer patients at risk of impaired capacity to consent to research. J Pain Symptom Manage 2003; 26:615–624Google Scholar

21. Casarett D, Karlawish J, Sankar P, Hirschman KB, Asch DA: Obtaining informed consent for clinical pain research: patients’ concerns and information needs. Pain 2001; 92:71–79Google Scholar

22. Berkowitz L, Lutterman KG: The traditional socially responsible personality. Public Opin Q 1968; 32:169–185Google Scholar

23. Rose A, Peters N, Shea JA, Armstrong K: Development and testing of the Health Care System Distrust Scale. J Gen Intern Med 2004; 19:57–63Google Scholar

24. Kim SY, Kim HM, McCallum C, Tariot PN: What do people at risk for Alzheimer disease think about surrogate consent for research? Neurology 2005; 65:1395–1401Google Scholar

25. Roberts JS: Anticipating response to predictive genetic testing for Alzheimer’s disease: a survey of first-degree relatives. Gerontologist 2000; 40:43–52Google Scholar

26. Cornoni J, Ostfeld A, Taylor J, Wallace R, Blazer D, Berkman L, Evans D, Kohout F, Lemke J, Scherr P: Establishing populations for epidemiologic studies of the elderly: study design and methodology. Aging 1993; 5:27–37Google Scholar

27. Liang K, Zeger S: Regression analysis for correlated data. Annu Rev Public Health 1993; 14:43–68Google Scholar

28. Columbia University Medical Center: Columbia University Institutional Review Board Policy: Informed Consent, May 8, 2007. http://www.cumc.columbia.edu/dept/irb/policies/documents/InformedConsentPolicy.50807.docGoogle Scholar

29. Michels R: Are research ethics bad for our mental health? N Engl J Med 1999; 340:1427–1430Google Scholar