The Relationship Between Avoidant Personality Disorder and Social Phobia: A Population-Based Twin Study

Abstract

Objective: The purpose of this study was to determine the sources of comorbidity for social phobia and dimensional representations of avoidant personality disorder by estimating to what extent the two disorders are influenced by common genetic and shared or unique environmental factors versus the extent to which these factors are specific to each disorder. Method: Young adult female-female twin pairs (N=1,427) from the Norwegian Institute of Public Health Twin Panel were assessed at personal interview for avoidant personality disorder and social phobia using the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality and the Composite International Diagnostic Interview. Bivariate Cholesky models were fitted using the Mx statistical program. Results: The best-fitting model included additive genetic and unique environmental factors only. Avoidant personality disorder and social phobia were influenced by the same genetic factors, whereas the environmental factors influencing the two disorders were uncorrelated. Conclusions: Within the limits of statistical power, these results suggest that there is a common genetic vulnerability to avoidant personality disorder and social phobia in women. An individual with high genetic liability will develop avoidant personality disorder versus social phobia entirely as a result of the environmental risk factors unique to each disorder. The results are in accordance with the hypothesis that psychobiological dimensions span the axis I and axis II disorders.

One of the most studied and controversial interactions between axis I and axis II disorders is that between social phobia and avoidant personality disorder (1 – 5) . Both diagnoses were first formally introduced on separate axes in DSM-III (6) , with a predetermined hierarchy such that social phobia could not be diagnosed in the presence of avoidant personality disorder. In DSM-III-R (7) this exclusion criterion was dropped, and several other changes were made, including the introduction of a generalized subtype of social phobia. Empirical studies based on patients seeking treatment for social phobia or other anxiety disorders showed substantial overlap between the two disorders, particularly the generalized form, leading several authors to conclude that they were not distinct disorders (reviewed by Reich [2] ). The criteria for both disorders were further revised in DSM-IV (8) .

A study on the prevalence of social phobia in subjects with avoidant personality disorder using DSM-IV criteria indicates that the overlap might be less than in studies based on patients with social phobia alone (9) . Since rates of comorbidity may be artificially raised in clinical samples (10) , population-based studies are necessary to determine the true degree of comorbidity. To our knowledge, only two population-based studies of avoidant personality disorder and social phobia have been published; both reported moderate degrees of co-occurrence (11 , 12) .

Comorbidity can result from a number of mechanisms (10 , 13) . However, several authors have suggested that social phobia and avoidant personality disorder are part of the same spectrum, implying that the co-occurrence can be explained by common etiological factors (e.g., references 3 – 5 , 14) . In a family study by Stein et al., relatives of probands with generalized social phobia had a significantly higher prevalence of avoidant personality disorder than first-degree relatives of comparison probands, suggesting that the two disorders share familial risk factors (15) . However, the study by Stein et al. could not determine to what extent this familial co-aggregation results from shared genetic or environmental factors. In contrast, twin studies such as the present study are well suited to test the hypothesis of overlapping etiological processes (10) .

In the present study we estimated the co-occurrence of avoidant personality disorder and social phobia in a study group consisting of young adult female-female twin pairs that participated in structured interviews for axis I and axis II disorders. Our aim was to determine the sources of covariation between the two disorders by applying bivariate twin models. Because of the low prevalence of avoidant personality disorder, we used a dimensional representation of this disorder. Specifically, we estimated to what extent social phobia and avoidant personality disorder are influenced by common genetic and shared or unique environmental factors and to what extent these factors are specific to each disorder.

Method

Subjects

Subjects for this study came from the Norwegian Institute of Public Health Twin Panel (NIPHTP). The twins were identified through information contained in the Norwegian Medical Birth Registry, established Jan. 1, 1967, which receives mandatory notification of all births. Two questionnaire studies have previously been conducted in this sample: the first wave in 1992 on twins born 1967–1974 and the second wave in 1998 on twins born 1967–1979. Altogether, 12,700 twins received the second wave questionnaire and 8,045 responded after one reminder (response rate 63%), including 3,334 pairs and 1,377 single responders. The NIPHTP is described in detail elsewhere (16) .

Data for analysis were derived from an interview study for axis I and axis II psychiatric disorders that began in 1999. Participants were recruited among the 3,153 complete pairs who, in the second wave questionnaire, agreed to participate in an interview study, and 68 pairs were drawn directly from the NIPHTP. Of these 3,221 eligible pairs, 0.8% were unwilling or unable to participate, and in an additional 16.2% of pairs, only one twin agreed to the interview. After two attempts at contact, 38.2% did not respond. Altogether 50.6% of the eligible female-female twin pairs were interviewed.

Zygosity was initially determined by questionnaire items previously shown to correctly categorize 97.5% of twin pairs (16) . In all but 385 twin pairs, zygosity was also determined by molecular methods based on the genotyping of 24 microsatellite markers. From this data we estimated that the misclassification rate for our subjects was 0.7%.

Assessments

A Norwegian version of the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality (SIDP-IV) (17) was used to assess personality disorders. This instrument has been used in a number of studies in many countries, including Norway (18 , 19) . The specific DSM-IV criterion associated with each set of questions was rated using the following scoring guidelines: 0=not present, 1=subthreshold, 2=present, and 3=strongly present. Behaviors, cognitions, and feelings predominating for most of the last 5 years were considered to be representative of the individual’s long-term personality functioning. The SIDP-IV was conducted after the axis I interview, which helped the interviewer in distinguishing longstanding behavior from temporary states due to an episodic psychiatric disorder. Interrater reliability was assessed based on two raters scoring 70 audiotaped interviews. Intraclass and polychoric correlations for the number of endorsed avoidant personality disorder criteria at the subthreshold level were 0.96 and 0.97, respectively. Reliability, measured as internal consistency by Cronbach’s alpha based on polychoric correlations, was 0.96.

Axis I disorders were assessed using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) and used in most major psychiatric surveys all over the world in recent years, including Norway (20 , 21) . It has been shown to have good test-retest and interrater reliability (22 , 23) . We used a Norwegian version based on the computerized DSM-IV version of the Munich-Composite International Diagnostic Interview (M-CIDI) (24) . The CIDI includes questions about age of onset, which is not assessed in the SIDP-IV.

The interviewers were mostly psychology students in their final phase of training or experienced psychiatric nurses. For the SIDP-IV, interviewers were trained by one psychiatrist and two psychologists with extensive previous experience with the instrument. For the CIDI, interviewers received a standardized training program administered by teachers certified by WHO. The interviewers were supervised closely during the data collection period. Interviews were carried out between June 1999 and May 2004 and were largely conducted in person. For practical reasons, 231 interviews (8.3%) were obtained by telephone. Each twin in a pair was interviewed by a different interviewer.

Approval was received from the Norwegian Data Inspectorate and the Regional Ethical Committee, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants after a complete description of the study.

Statistical Analysis

Only female-female twin pairs were included in this investigation because biometric modeling was not possible for social phobia in male subjects due to low prevalence rates. The prevalence of categorical diagnoses of avoidant personality disorder in our study group was also too low to permit useful analysis. We therefore used a dimensional approach (25) , constructing ordinal variables based on the number of endorsed criteria. To optimize statistical power and produce maximally stable results, we used a number of subthreshold criteria (³1), assuming that the liability for each trait was continuous and normally distributed, i.e., that the classification (0–3) represented different degrees of severity. This assumption was evaluated using multiple threshold tests for each of the criteria. The same procedure was used to test the assumption that the total number of positive criteria for avoidant personality disorder represented different degrees of severity. All of the multiple threshold tests were done separately for each zygosity group, and none was significant (all p values >0.05). Because the number of subjects who endorsed all or most of the criteria for the disorder was small, we collapsed the upper categories for the total summed score, resulting in an ordinal variable that included four subcategories.

In the classical twin model used in this study, individual differences in liability are assumed to arise from three latent factors: additive genetic factors (A) (i.e., genetic effects that combine additively); common or shared environmental factors (C), including all environmental exposures that are shared by the twins and contribute to their similarity; and individual-specific or unique environmental factors (E), including all environmental factors not shared by the twins, plus random measurement error. Because monozygotic twins share all their genes and dizygotic twins share on average 50% of their segregating genes, genetic factors (A) contribute twice as much to twin resemblance for a particular trait or disorder in monozygotic twins compared with dizygotic twins. Both monozygotic and dizygotic twins are assumed to share all of their C factors and none of their E factors.

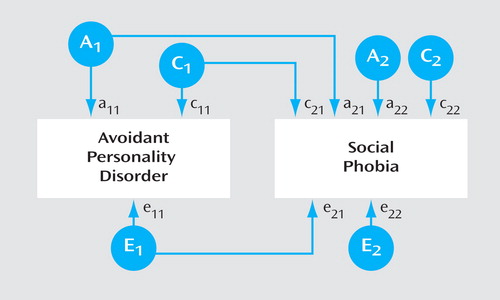

Model fitting was performed using the Mx statistical program (26) . To test the degree to which the covariation between social phobia and avoidant personality disorder resulted from common factors, we applied a bivariate Cholesky structural equation model (27) , specifying three latent factors (A 1 , C 1 , and E 1 ) with pathways influencing both avoidant personality disorder (a 11 , c 11 , e 11 ) and social phobia (a 21 , c 21 , e 21 ), in addition to three factors (A 2 , C 2 , and E 2 ) accounting for residual influences specific to social phobia only (a 22 , c 22 , e 22 ) ( Figure 1 ). Pathways a 21 , c 21 , and e 21 , from A 1 , C 1 , and E 1 , respectively, represent genetic and environmental effects shared by both phenotypes. The choice of ordering was based on the assumption that avoidant personality disorder should be the “upstream” variable because it is by definition a stable lifelong trait, whereas social phobia, although often a chronic disorder, could be episodic (8) . This model permitted the calculation of correlations between genetic factors (r a ), shared environmental factors (r c ), and unique environmental factors (r e ) that influence the two phenotypes. A full model, including all latent variables (ACE), was compared with nested submodels with reduced numbers of parameters. The fit of the alternative models was compared using the difference in twice the log likelihood values, which under certain regular conditions is asymptomatically distributed as χ 2 , with degrees of freedom (df) equal to the difference in the number of parameters. According to the principle of parsimony, models with fewer parameters are preferable if they do not result in a significant deterioration of fit. A useful index of parsimony is Akaike’s information criterion, which is calculated as Dc 2 –2Ddf (28) .

a A, C, and E stand for additive genetic, shared environmental, and unique environmental factors, respectively. Factors numbered 1 influence both phenotypes. Factors numbered 2 are specific to social phobia only. a, c, and e stand for additive genetic, shared environmental, and unique environmental pathways, respectively. Subscripts 11 and 21 indicate pathways from the first set of genetic and environmental factors. Subscript 22 indicates pathways from genetic and environmental factors specific to social phobia only.

A basic assumption in traditional twin analysis is that monozygotic and dizygotic twins are equally correlated in their exposure to trait-relevant environments. We tested the validity of this assumption by applying polychotomous logistic regression and controlled for the correlational structure of our data using independent estimating equations, in accordance with SAS procedure GENMOD (29) . Two variables that reflected similarity in childhood and adult environments, respectively, were constructed. In each twin pair we tested whether the avoidant personality disorder score or social phobia status in twin 1 interacted with our measure of environmental similarity in predicting the avoidant personality disorder score or social phobia status in twin 2. We controlled for the effects of zygosity, sex, age, and level of environmental similarity, as well as shared environmental effects and genetic effects. None of the four analyses testing the impact of environmental similarity on twin resemblance for avoidant personality disorder and social phobia approached significance (all p values >0.10).

Results

Of the participating female-female twin pairs, 1,427 (898 monozygotic, 529 dizygotic) had valid data on both social phobia and avoidant personality disorder. The mean age of the participants was 28.1 years (range=19–36). The prevalence of avoidant personality disorder and lifetime social phobia was, respectively, 2.7% (N=39) and 5.0% (N=71). In subjects with avoidant personality disorder, 32.5% also satisfied criteria for social phobia, and 18.3% of subjects with social phobia satisfied criteria for avoidant personality disorder. In subjects with 12-month social phobia (3.2%, N=46), 26.1% had co-occurring avoidant personality disorder, and the prevalence of avoidant personality disorder in subjects who fulfilled the criteria for generalized social phobia (2.5%, N=36) was 30.6%. The association between avoidant personality disorder and lifetime and 12-month social phobia, expressed as odds ratios (OR) and taking into account the clustered nature of twin data, was 11.97 (95% confidence interval [CI]=5.36–24.54) and 17.70 (95% CI=7.84–39.95), respectively. The mean age of onset for lifetime social phobia with and without avoidant personality disorder was 12.5 years (SD=4.7) and 12.8 years (SD=5.8), respectively.

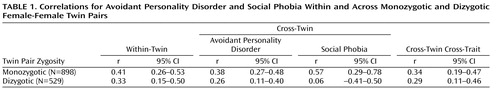

There were no significant differences in thresholds for lifetime social phobia and the dimensional representation of avoidant personality disorder within pairs or across zygosity. Table 1 shows twin correlations (within-twin, cross-twin, and cross-twin cross-trait) for each zygosity group. The higher correlations in monozygotic twins compared with dizygotic twins indicate genetic effects both for social phobia and avoidant personality disorder and for the covariation.

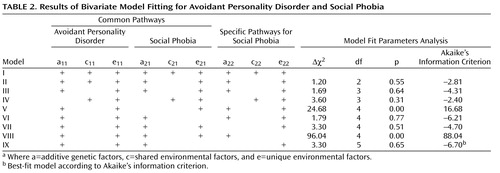

The results of model fitting are shown in Table 2 . The full ACE model (model I) included all pathways from both sets of latent factors. In model II we constrained both of the C pathways for social phobia (c 21 , c 22 ) to zero. This resulted in an improvement in fit as measured by Akaike’s information criterion. An AE model constraining the C pathways for both avoidant personality disorder and social phobia to zero (model III) provided a further improvement in fit, whereas a CE model specifying no additive genetic effects (model IV) fit the data less well. The AE model (model III) was therefore used as a basis for subsequent model fitting. To compare the relative influence of A and E on the comorbidity of avoidant personality disorder and social phobia, the common and the specific A and E paths were in turn constrained to zero (models V–VIII). Dropping the common A path (a 21 ) resulted in a very poor fit (model V), whereas dropping the common E path (e 21 ) resulted in a substantial improvement in fit (model VI). This indicates both a significant contribution by additive genetic factors and little effect of E on the covariance between avoidant personality disorder and social phobia. Constraining to zero the specific A path (a 22 ) for social phobia (model VII) resulted in a modest improvement in Akaike’s information criterion, but dropping the specific E path (e 22 ) for social phobia (model VIII) resulted in a significant deterioration in fit. To test if model VI could be further improved, we dropped the specific A path for social phobia (model IX). This model, which specified only one latent A factor influencing both avoidant personality disorder and social phobia and two specific E factors without any common E pathway, fit the data best, but only slightly better than model VI.

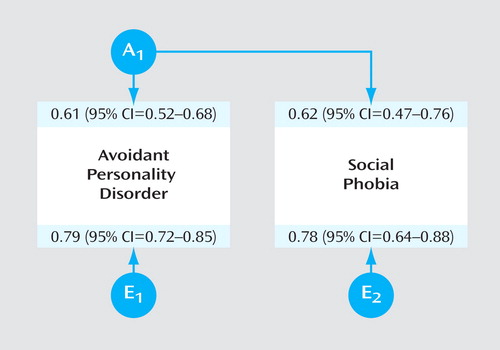

The best-fit model indicates that the same genes influence both social phobia and avoidant personality disorder (r a =1) and that the two disorders are affected by a distinct set of environmental factors (r e =0) ( Figure 2 ). The model estimates heritability for avoidant personality disorder and social phobia as 37% and 39%, respectively. The genetic and environmental correlations in the full model (model I) were: r a =0.68 (95% CI=0.00–1.00), r c =1.00 (95% CI=0.00–1.00), and r e =0.07 (95% CI=0.00–0.33); in the second best model (model VI): r a =0.81 (95% CI=0.56–1.00) and r e =0.00. The two best models (models VI and IX) fit almost equally well, with a difference in Akaike’s information criterion of –0.49. Although we cannot with confidence rule out that a small part of the additive genetic effects are not shared between avoidant personality disorder and social phobia, the high genetic correlation in the second best model suggests that the genetic liabilities for the two disorders are, at a minimum, highly correlated. None of the models compatible with the data indicated that common unique environmental factors contributed significantly to the covariation between the two disorders (all 95% CIs for r e included 0.00).

a A and E stand for additive genetic and unique environmental factors, respectively.

Discussion

We found a moderate degree of overlap between avoidant personality disorder and social phobia in the participants. Although most of the subjects with both avoidant personality disorder and social phobia manifested only one of the disorders, we cannot rule out that the two disorders are alternative conceptualizations of the same disorder (2 , 4) .

Our results are best compared with other population-based studies. Using a 12-month diagnosis of social phobia, Lampe et al. (11) and Grant et al. (12) found a prevalence rate of 28.9% and 30.3%, respectively, for avoidant personality disorder in subjects with social phobia. This is similar to our estimated prevalence of 26.1% for avoidant personality disorder in subjects with 12-month social phobia. Grant et al. determined an odds ratio of 27.3 for the association between the two disorders, which was somewhat higher than our estimate, but not significantly different (OR=17.70; 95% CI=7.84–39.95). Lampe et al. only reported a multivariate odds ratio (3.9), controlling for comorbid disorders. The 12-month prevalence of social phobia in our study (3.2%) is very similar to the estimates in these studies (2.5% and 2.8%), and our prevalence for avoidant personality disorder (2.7%) is similar to Grant et al.’s estimate (2.4%), but somewhat lower than that reported by Lampe et al. (6.5%).

This is the first study to examine the genetic and environmental sources of the relationship between avoidant personality disorder and social phobia. The best-fit model, which includes only genetic and individual-specific environmental factors, shows that, within the limits of study design and statistical power (30 , 31) , the covariation between the disorders can be explained solely by common genetic factors; i.e., the genetic risk factors for social phobia and avoidant personality disorder appear to be identical. On the other hand, the environmental risk factors influencing avoidant personality disorder and social phobia appear to be unique to each disorder. We cannot rule out that some of the environmental risk factors for the two disorders are shared in common, but even in the full model (model I) the correlation between these factors was not significant (r e =0.07; 95% CI=0.00–0.33). This suggests that given a high genetic liability on the avoidant personality disorder/social phobia dimension, the probability of developing avoidant personality disorder or social phobia is a result of different environmental experiences; i.e., different kinds of life events predispose someone to avoidant personality disorder versus social phobia. Individuals exposed to both sets of environmental factors will develop both disorders. From this study, it is not possible to tell what such environmental experiences would be.

Given the moderate size of the study group and the use of dichotomous and ordinal variables, we cannot rule out with confidence common environmental effects (30 , 31) , even though the CE model fit the data less well than the AE model, and in both of the univariate analyses the AE model fit best. Indeed, in the full ACE univariate model of social phobia, as well as in the full bivariate model, C was estimated to be zero and could be dropped without any reduction in fit. For avoidant personality disorder and avoidant personality disorder-like traits, previous studies have found that AE models fit the data best, and our heritability estimates are within the same range (32 , 33) . In most previous studies of social phobia and social anxiety-related concerns and personality characteristics, AE models have been found to fit the data best (34 – 36) , and our heritability estimate is within the same range as in these studies. However, other studies have reported mixed results with regard to the effect of shared environmental influences (37 , 38) .

Our results are in accordance with previous hypotheses that the two disorders are part of the same spectrum. Siever and Davis (14) have proposed a dimensional classification of personality disorders with four core psychobiological predispositions that span both axis I and axis II disorders: cognitive/perceptual organization, impulsivity aggression, affective instability, and anxiety/inhibition. Although their theory primarily addresses the psychobiological level of causation, they hypothesize that “anxiety/inhibition is a dimension of personality genetically related to the axis I anxiety disorders” (14) . Our results support this hypothesis and are also consistent with Shea et al.’s finding of significant longitudinal association between social phobia and avoidant personality disorder (3) .

In this study we only tested models of common etiological mechanisms and did not address the possibility of phenotypic causality (e.g., avoidant personality disorder causes social phobia), which would imply that one disorder precedes the other. However, the young age of onset for social phobia in our subjects (mean=12.8 years), similar to the age of onset for social phobia found in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (median=13 years) (39) , indicates that such a model of causation is unlikely.

This is the first study to apply bivariate twin analysis to the relationship between avoidant personality disorder and social phobia and to demonstrate a common genetic vulnerability, supporting Siever and Davis’s hypothesis of an underlying psychobiological dimension spanning axis I/axis II disorders. If replicated, this finding raises a fundamental question about classification in DSM-V. Should disorders be grouped into classes based on etiology (e.g., genetics), phenotypic features (i.e., prominent symptoms), or stability of course and age of onset (cited in DSM-IV [8] as the main criteria for distinguishing between axis I and II disorders)?

Limitations

Several potential limitations should be considered in the interpretation of these results. First, because of the low prevalence, we were unable to analyze categorical avoidant personality disorder diagnoses and instead examined a dimensional representation of the DSM-IV diagnosis. Since twin analyses are based on a liability threshold model, it should make no difference if the studied variable is dimensional, as long as it reflects the same underlying liability as the categorical diagnosis. We supported this assumption using multiple threshold tests for each individual criterion and for each of the dimensional representations of the disorder. Second, we were not able to include male subjects in our analyses. Although most previous studies have found no difference between the sexes in heritability for social phobia (34 , 38) , one study did (37) . Given this uncertainty, our results for women may not extrapolate to men. Furthermore, we only studied young Norwegian adults, and our findings may not extrapolate to other ethnic groups or age cohorts. Third, although we included a large number of twin pairs, substantial attrition was observed in this study group. We are currently preparing detailed analyses of the predictors of nonresponse. To summarize briefly, cooperation was strongly and consistently predicted by female gender, monozygosity, older age, and higher educational status, but not by symptoms of mental disorder. In particular, we assessed personality disorder traits from the NIPHTP second wave questionnaire using 91 self-reported items. Multiple linear regression analysis was used to compare these items in predicting the number of endorsed avoidant personality disorder criteria. The polychoric correlation between the questionnaire items and those from the interview was 0.60. Screening items for social phobia in the questionnaire had a correlation of 0.43 with a social phobia diagnosis in the CIDI interview. Avoidant personality disorder and social phobia scores from the second wave questionnaire did not significantly predict participation in the personal interview, when controlled for demographic variables. Finally, each of the twins was interviewed only once. Although we demonstrated high interrater reliability and internal consistency, we could not estimate the test-retest reliability over time. Previous studies have shown that the long-term test-retest reliability of social phobia and avoidant personality disorder is moderate (34 , 40) . In twin analyses, random measurement errors are reflected in unique environmental factors (E), which implies that a reduction in reliability would result in decreased heritability estimates. However, estimates of the degree to which genetic and environmental factors influence the covariation between avoidant personality disorder and social phobia would not be affected by measurement errors in this study, because the E factors influencing the two disorders were not significantly correlated.

1. Widiger TA: Generalized social phobia versus avoidant personality disorder: a commentary on three studies. J Abnorm Psychol 1992; 101:340–343Google Scholar

2. Reich J: The relationship of social phobia to avoidant personality disorder: a proposal to reclassify avoidant personality disorder based on clinical empirical findings. Eur Psychiatry 2000; 15:151–159Google Scholar

3. Shea MT, Stout RL, Yen S, Pagano ME, Skodol AE, Morey LC, Gunderson JG, McGlashan TH, Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, Bender DS, Zanarini MC: Associations in the course of personality disorders and axis I disorders over time. J Abnorm Psychol 2004; 113:499–508Google Scholar

4. Ralevski E, Sanislow CA, Grilo CM, Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Tracie SM, Yen S, Bender DS, Zanarini MC, McGlashan TH: Avoidant personality disorder and social phobia: distinct enough to be separate disorders? Acta Psychiatr Scand 2005; 112:208–214Google Scholar

5. Dolan-Sewell RT, Krueger RF, Shea MT: Co-occurrence with syndrome disorders, in Handbook of Personality Disorders: Theory, Research and Treatment. Edited by Livesley WJ. New York, Guilford Press, 2001, pp 84–104Google Scholar

6. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed. Washington, DC, APA, 1980Google Scholar

7. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed., revised. Washington, DC, APA, 1987Google Scholar

8. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, APA, 1994Google Scholar

9. McGlashan TH, Grilo CM, Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Shea MT, Morey LC, Zanarini MC, Stout RL: The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: baseline axis I/II and II/II diagnostic co-occurrence. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000; 102:256–264Google Scholar

10. Neale MC, Kendler KS: Models of comorbidity for multifactorial disorders. Am J Hum Genet 1995; 57:935–953Google Scholar

11. Lampe L, Slade T, Issakidis C, Andrews G: Social phobia in the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being (NSMHWB). Psychol Med 2003; 33:637–646Google Scholar

12. Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan WJ, Huang B: Co-occurrence of 12-month mood and anxiety disorders and personality disorders in the US: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Psychiatr Res 2005; 39:1–9Google Scholar

13. Lyons MJ, Tyrer P, Gunderson J, Tohen M: Heuristic models of comorbidity of axis I and axis II disorders. J Personal Disord 1997; 11:260–269Google Scholar

14. Siever LJ, Davis KL: A psychobiological perspective on the personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1647–1658Google Scholar

15. Stein MB, Chartier MJ, Hazen AL, Kozak MV, Tancer ME, Lander S, Furer P, Chubaty D, Walker JR: A direct-interview family study of generalized social phobia. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:90–97Google Scholar

16. Harris JR, Magnus P, Tambs K: The Norwegian Institute of Public Health Twin Panel: a description of the sample and program of research. Twin Res 2002; 5:415–423Google Scholar

17. Pfohl B, Blum N, Zimmerman M: Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality (SIDP-IV). Iowa City, University of Iowa, Department of Psychiatry, 1995Google Scholar

18. Torgersen S, Kringlen E, Cramer V: The prevalence of personality disorders in a community sample. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:590–596Google Scholar

19. Helgeland MI, Kjelsberg E, Torgersen S: Continuities between emotional and disruptive behavior disorders in adolescence and personality disorders in adulthood. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:1941–1947Google Scholar

20. Kringlen E, Torgersen S, Cramer V: A Norwegian psychiatric epidemiological study. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1091–1098Google Scholar

21. Landheim AS, Bakken K, Vaglum P: Gender differences in the prevalence of symptom disorders and personality disorders among poly-substance abusers and pure alcoholics: substance abusers treated in two counties in Norway. Eur Addict Res 2003; 9:8–17Google Scholar

22. Wittchen HU: Reliability and validity studies of the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): a critical review. J Psychiatr Res 1994; 28:57–84Google Scholar

23. Wittchen HU, Lachner G, Wunderlich U, Pfister H: Test-retest reliability of the computerized DSM-IV version of the Munich-Composite International Diagnostic Interview (M-CIDI). Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1998; 33:568–578Google Scholar

24. Wittchen HU, Pfister H (eds): DIA-X-Interviews: Manual für Screening-Verfahren und Interview; Interviewheft Längsschnittuntersuchung (DIA-X-Lifetime); Ergänzungsheft (DIA-X Lifetime); Interviewheft Querschnittuntersuchung (DIA-X-12 Monate); Ergänzungsheft (DIA-X-12 Monate); PC-Programm zur Durchführung des Interviews (Längs-und Querschnittuntersuchung); Auswertungsprogramm. Frankfurt, Swets & Zeitlinger, 1997Google Scholar

25. Widiger TA, Samuel DB: Diagnostic categories or dimensions? a question for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—fifth edition. J Abnorm Psychol 2005; 114:494–504Google Scholar

26. Neale MC, Boker SM, Xie G, Maes HH: Mx: Statistical Modeling, 5th ed. Richmond, Virginia Commonwealth University, Medical College of Virginia, 1999Google Scholar

27. Neale MC, Cardon LR: Methodology for Genetic Studies of Twins and Families. Dordrecht, the Netherlands, Kluver Academic Publishers, 1992Google Scholar

28. Akaike H: Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrika 1987; 52:317–332Google Scholar

29. SAS OnlineDoc 9.1.3. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 2005Google Scholar

30. Neale MC, Eaves LJ, Kendler KS: The power of the classical twin study to resolve variation in threshold traits. Behav Genet 1994; 24:239–258Google Scholar

31. Sullivan PF, Eaves LJ: Evaluation of analyses of univariate discrete twin data. Behav Genet 2002; 32:221–227Google Scholar

32. Jang KL, Livesley WJ, Vernon PA, Jackson DN: Heritability of personality disorder traits: a twin study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1996; 94:438–444Google Scholar

33. Torgersen S, Lygren S, Oien PA, Skre I, Onstad S, Edvardsen J, Tambs K, Kringlen E: A twin study of personality disorders. Compr Psychiatry 2000; 41:416–425Google Scholar

34. Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Prescott CA: Fears and phobias: reliability and heritability. Psychol Med 1999; 29:539–553Google Scholar

35. Nelson EC, Grant JD, Bucholz KK, Glowinski A, Madden PAF, Reich W, Heath AC: Social phobia in a population-based female adolescent twin sample: co-morbidity and associated suicide-related symptoms. Psychol Med 2000; 30:797–804Google Scholar

36. Stein MB, Jang KL, Livesley WJ: Heritability of social anxiety-related concerns and personality characteristics: a twin study. J Nerv Ment Dis 2002; 190:219–224Google Scholar

37. Kendler KS, Jacobson KC, Myers J, Prescott CA: Sex differences in genetic and environmental risk factors for irrational fears and phobias. Psychol Med 2002; 32:209–217Google Scholar

38. Hettema JM, Prescott CA, Myers JM, Neale MC, Kendler KS: The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for anxiety disorders in men and women. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62:182–189Google Scholar

39. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE: Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62:593–602Google Scholar

40. McGlashan TH, Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, Ralevski E, Morey LC, Gunderson JG, Skodol AE, Shea MT, Zanarini MC, Bender D, Stout RL, Yen S, Pagano M: Two-year prevalence and stability of individual DSM-IV criteria for schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders: toward a hybrid model of axis II disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:883–889Google Scholar