Negative Signs and Symptoms Secondary to Antipsychotics: A Double-Blind, Randomized Trial of a Single Dose of Placebo, Haloperidol, and Risperidone in Healthy Volunteers

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Despite the clinical observation that antipsychotics can produce negative symptoms, no previous controlled study, to our knowledge, has evaluated this action in healthy subjects. The present study assessed observer-rated and self-rated negative symptoms produced by conventional and second-generation antipsychotics in healthy volunteers. METHOD: The authors used a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of single doses of haloperidol (5 mg) and risperidone (2.5 mg) in normal subjects. Thirty-two subjects were administered haloperidol, risperidone, and placebo in a random order. Motor variables and observer-rated negative symptoms were assessed after 3–4 hours and subjective negative symptoms and drowsiness after 24 hours. RESULTS: Neither of the active drugs caused significant motor extrapyramidal symptoms after administration. Haloperidol caused significantly more negative signs and symptoms than placebo on the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) and two self-rated negative symptom scales: the Subjective Deficit Syndrome Scale total score and an analog scale that evaluates subjective negative symptoms. Risperidone caused significantly more negative signs and symptoms than placebo on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), the SANS, the Subjective Deficit Syndrome Scale total score, and the analog scale for subjective negative symptoms. After control for drowsiness, risperidone but not haloperidol produced more negative symptoms than placebo on the BPRS and the SANS. Significance was lost for the subjective negative symptoms with both drugs. CONCLUSIONS: Single doses of both haloperidol and risperidone produce negative symptoms in normal individuals. Drowsiness may be an important confounding factor in the assessment of negative symptoms in antipsychotic trials.

Since the therapeutic effects of antipsychotics were first discovered, it has been clear that they produce undesirable as well as target effects, some of which are difficult to distinguish from the negative symptoms of schizophrenia (1–5). Motor side effects can mimic negative symptoms, as well as nonmotor type effects, including indifference, apathy, and avolition. These effects have been more frequently described in patient self-reports than in observations made by clinicians. These drug-induced side effects are difficult to distinguish from primary or other sources of secondary negative symptoms (6, 7).

Both first- and second-generation antipsychotics reduce negative symptom ratings in schizophrenia. Several studies (8, 9) have reported higher efficacy in negative symptoms with second-generation antipsychotics than with haloperidol; however, the differential effect may be lost when low doses of haloperidol are used (10).

The effect of antipsychotics on primary negative symptoms is more controversial. Two general approaches have been applied to address this issue. On one hand, primary negative symptoms have been defined as observer-rated negative symptoms that cannot be explained by positive symptoms, depressive symptoms, or antipsychotic-produced motor extrapyramidal symptoms. Statistical techniques have evolved from simpler, correlational, and covariant strategies (11–13) to more sophisticated ones, such as path analysis (8, 9, 14). The unexplained variance is interpreted as a direct treatment effect on primary negative symptoms. However, there are also other sources of secondary negative symptoms, and nonmotor effects of antipsychotics could be considered primary negative symptoms. Therefore, to deal with this, some investigators use a clinically defined and rated condition called the “deficit syndrome.” To be categorized as such, all known sources of secondary negative symptoms have to be ruled out, and the negative symptoms have to be long-lasting, with a longitudinal assessment (15–17).

Negative symptoms are easy to measure in schizophrenia patients but difficult to attribute to a precise source. To clarify these ambiguities, we studied healthy subjects free of any psychiatric symptoms. We assessed all negative symptoms in healthy subjects in response to single doses of haloperidol or risperidone in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. We quantified the subjective experiences of treated individuals as well as the observed effects. According to our hypothesis, haloperidol would cause the most negative symptoms as measured by observer-rated and subjective measures and placebo the least.

Method

Subjects

The subjects were recruited from advertisements placed in the Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre in Madrid and met the following criteria: ages 18 to 60 years, no psychiatric disorder according to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV for normal volunteers, not receiving psychotropic drugs, no drug or alcohol abuse or dependence (except for nicotine), and no other relevant medical condition. The hospital’s ethical committee for research with humans approved the research protocol. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects after we fully explained the procedure.

Design

A within-subject design was carried out with haloperidol and risperidone. Each participant was interviewed and rated four times. The first interview established baseline variables (with handwriting and a videotaped interview). The subsequent three interviews were identical and were performed after double-blind random assignment of the sequence with which placebo, haloperidol, and risperidone were to be administered.

Procedure

Because of ethical considerations, only single low doses of the substances were administered in liquid formulations of placebo, haloperidol (5 mg), or risperidone (2.5 mg). Water and lemon extract were added to the substances to ensure double-blind conditions (18). The 2.5-mg dose of risperidone was chosen as the equivalent of 5 mg of haloperidol (19, 20).

The baseline assessments were repeated at two different time points. The first evaluation (clinician-rated scales) was made at the time the substances reached their highest plasma level (Tmax). Tmax for haloperidol is 1.7–6.1 hours (21); it is 0.8 hour (SD=0.3) for risperidone, and 3.2 hours (SD=1.5) for its active metabolite 9-hydroxyrisperidone (22). Therefore, ratings were performed between 3 and 4 hours after administration for the first assessment. The second assessment (self-rated scales) was performed 24 hours after administration and assessed cumulative subjective experiences over the previous 24 hours. The minimum washout period between administrations was 48 hours based on half-lives of haloperidol (14.5–36.7 hours) (21), risperidone (mean=2.8 hours, SD=0.5), and 9-hydroxyrisperidone (mean=20.5 hours, SD=2.9) (22).

Motor Signs

Parkinsonism and akathisia were evaluated with standardized scales: the Simpson-Angus Rating Scale (23) and the Barnes Rating Scale for Drug-Induced Akathisia (24), respectively. Handwriting was evaluated as another variable of motor outcome. Decreased handwriting area has been described as a more precise way to rate motor extrapyramidal symptoms, in correlation with dopamine D2 receptor occupancy (25).

Observer-Rated Negative Symptoms

Negative symptoms were assessed with 1) the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (26) negative symptoms subscale and 2) the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) (27) alogia and affect flattening items. Alogia and affective flattening were selected from the other items because they appear in several factor analyses in the negative syndrome, and they do not require a full week of observation. Instead of referring to illness during the interview, because the participants did not have schizophrenia, they were asked to talk about their most recent holidays. Both of the raters were psychiatrists (J.F.A. and J.S.). Interrater reliability scores (intercorrelation coefficients) for the two raters on these scales were between 0.80 and 0.92 for each BPRS item, each of the two SANS items, and the Simpson-Angus Rating Scale and Barnes Rating Scale for Drug-Induced Akathisia total scores. All four interviews (baseline and after administration of the placebo and the two drugs) were videotaped, and the raters made a consensus rating after watching the taped interviews.

Subjective Negative Symptoms

The Subjective Deficit Syndrome Scale was applied (28). This scale asks subjects to rate, from 0 to 4, aspects regarding lack of energy, blunted affect, and difficulty in or altered thinking, including, “Do you tire easily (complaints about excessive fatigue)?” “Have you lost the ability to feel emotions (apathy)?” “Do you have problems concentrating (subjective problems with concentration)?” An analog scale (29) of subjective negative symptoms was also developed based on Huber’s basic symptoms (30) (the scale is available upon request from the first author). Both scales were self-reported.

Drowsiness

This concept is defined on the basis of Lewander’s consideration of sedation, which distinguishes between a more general somnolence effect versus a more lethargic effect (4). An analog scale (29) was developed to measure the sedative or somnolent effect. These scales present a line with two ends; each end expresses a specific maximum and minimum for the variable being evaluated. The subject is asked to make a mark on the line representing how he or she feels. (The scale is available upon request from the first author.) This variable was considered a possible confounding factor in the rating of observer-rated and self-rated negative symptoms.

Data Analysis

A balanced crossover experimental design was used, with the three treatments and six possible sequences of administration to address the issue of treatment order. Five individuals were randomly included in each sequence.

Data were analyzed as usual in this type of design with repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) and treatment and order of administration as fixed factors. The overall null hypothesis (placebo=haloperidol=risperidone) was tested for each outcome measured by using a continuous variable. If this null hypothesis was rejected, pairwise tests of the differences between treatments (haloperidol versus placebo, risperidone versus placebo, and risperidone versus haloperidol) were then performed with Student’s t test with Bonferroni correction. When the outcome was measured with a noncontinuous variable (Barnes Rating Scale for Drug-Induced Akathisia, the Simpson-Angus Rating Scale, or the SANS), only pairwise comparisons were made because the number of observations was insufficient to guarantee the requirements of the overall test.

A significance level of 0.05 was established. Some outcomes that might be affected by drowsiness, specifically observer- and self-rated negative symptoms, were included in the model as covariates. To rule out any possible confounding effect of other epidemiological variables (gender, age, smoking status, level of education, or body mass index), we applied ANOVA and chi-square tests to be sure that they were not correlated with the sequence of administration.

Results

Thirty-two subjects entered the study. Thirty subjects completed it; one person dropped out voluntarily, whereas another was eliminated after suffering a hypotensive episode with risperidone. Of the completer group, 17 were women and 13 were men; the mean age was 32.4 years (SD=10.5, range=18–58). Ten of the completers were smokers. Mean education in years was 17.1 (SD=1.6, range=12–18). Body mass index was 24.7 kg/m2 (SD=7.1, range=18.8–38.1). The variables were homogeneously distributed in the different groups and randomly assigned to the different sequences of drug administration. No significant differences attributable to the order of administration were detected for any of the variables.

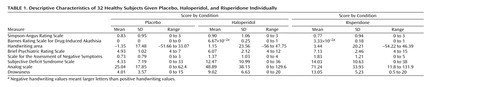

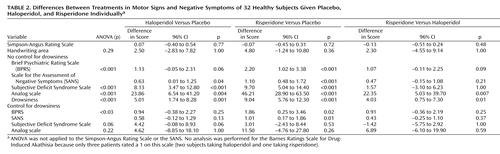

Descriptive characteristics and differences between treatments, before and after control for drowsiness, are shown in Table 1 and Table 2. As for motor symptoms, one subject reported acute buccolingual dystonia 20 hours after receiving haloperidol. No significant differences were detected between drugs for the Simpson-Angus Rating Scale score or the handwriting area. No analysis was performed for the Barnes Rating Scale for Drug-Induced Akathisia because only three patients rated a 1 on this scale (two subjects taking haloperidol and one taking risperidone). The participants taking risperidone scored significantly higher on the BPRS negative symptoms subscale than those receiving placebo; likewise, the individuals receiving haloperidol or risperidone scored significantly higher on the SANS items versus those receiving placebo. The participants taking haloperidol or risperidone scored significantly higher on the two self-rated scales than those receiving placebo (Table 1 and Table 2). The subjects scored significantly higher on drowsiness after taking either haloperidol or risperidone versus those receiving placebo; in a comparison of the two drugs, they scored higher with risperidone than with haloperidol (Table 1 and Table 2). After control for drowsiness, only those taking risperidone scored significantly higher than those receiving placebo on the BPRS and SANS negative symptom items (Table 2).

Discussion

The results of the current study indicate that single-dose administration of both haloperidol and risperidone produces negative symptoms in healthy volunteers, according to both clinician-rated and self-report scales. Neither of the drugs produced significant motor extrapyramidal symptoms, as measured by the Simpson-Angus Rating Scale or the handwriting area, based on the findings of this single-dose study. Negative symptoms were found in the absence of a detectable motor extrapyramidal component. In the case of risperidone, negative symptoms were also independent of a sedative effect.

Treatment-induced nonmotor negative symptoms are not taken into account in studies in which primary negative symptoms are defined as observer-rated negative symptoms that cannot be explained by positive, depressive, and motor symptoms (8, 9, 14). Because our normal comparison subjects lacked any initial psychopathology, the drug-induced nature of these symptoms is clear. Thus, we can say that the symptoms are “nonmotor” negative symptoms secondary to antipsychotics. In the studies cited (8, 9, 14), unexplained variance is interpreted as a direct treatment effect exerted on primary negative symptoms by different second-generation antipsychotics. In these studies, antipsychotic-induced “nonmotor” negative symptoms could have been considered primary negative symptoms. The estimates of effect size for the medication-induced negative symptoms found in the present study could be useful in evaluating findings from pharmacological trials of agents that target negative symptoms.

Some authors (4) give definitions for unspecific sedation (drowsiness) and specific sedation (Rifkin’s akinesia, which we have called negative signs and symptoms secondary to antipsychotics) that clearly differentiate them conceptually. Nonetheless, we find it complicated to distinguish between them in this manner. In fact, in the present study, subjective negative symptoms scales could not clearly distinguish between drowsiness and negative signs and symptoms secondary to antipsychotics. The information provided by these scales must be questioned until they can distinguish more clearly between these two factors. This idea receives strong support from data from various authors and clinical descriptions. The point is clarified further by Laborit’s description:

The patients required less analgesics and, at the same time, had an unusual state of consciousness in that they were readily aroused but seemed unconcerned with the environmental situation. (1)

and by an unprompted written report by one of our subjects:

I feel slow but not sleepy. During the interview I feel clumsy, and I want to finish as soon as possible (it’s difficult for me to explain what is happening to me).

Drowsiness was also used as a possible confounding factor in the rating of observer-rated negative symptoms scales (BPRS and SANS). Albeit to a lesser degree than the “subjective” scales in our study, these scales were also affected to the point of rendering insignificant the difference between haloperidol and placebo. However, the differences between risperidone and placebo remained significant. Drowsiness is hardly ever controlled in the statistical approaches used to demonstrate the effect of drugs on primary negative symptoms. Moreover, high doses of benzodiazepines can provoke drowsiness, and this factor might be confounded with observer-rated negative symptoms.

An interpretation of the differences between haloperidol and risperidone depends on their equivalent doses. Several studies have suggested that the doses chosen in the present study were equipotential. The 1997 APA guidelines (19) indicated that a 1–2-mg dose of risperidone equals a 2-mg dose of haloperidol and that haloperidol may require doses double those of risperidone. Schotte et al. (20) measured the occupancy of central neurotransmitter receptors by haloperidol and risperidone in an ex vivo quantitative autoradiography. Doses of 0.048 mg/kg of haloperidol and 0.11 mg/kg of risperidone were needed to induce 25% D2 receptor occupancy in the caudate-putamen. However, other studies have supported equivalent dosing (31).

Our study group consisted of healthy individuals receiving single doses of antipsychotics. The effect of antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia may differ from that seen in this study with normal comparison subjects. The study was conducted with a single dose, and the effect of these antipsychotics on the variables assessed could change in chronic settings. Nevertheless, both a review of the literature and clinical experience support the finding that antipsychotics produce negative signs and symptoms secondary to antipsychotics, not only in healthy subjects as shown in the present study but also in schizophrenia patients in long-term treatment. A further limitation was that a benzodiazepine arm was not included, which would have made it possible to compare the purer sedative effect and the neuroleptic effect caused by the antipsychotics. Drowsiness and subjective negative symptoms were assessed by self-rated scales 24 hours after drug administration to detect all symptoms that appeared during the entire 24-hour period. However, the observer-rated negative symptoms and motor variables were measured after 3–4 hours. Correction for those variables with another variable evaluated at a later time point could be a potential confounding factor. Finally, the dose chosen might have favored risperidone versus haloperidol, because although some reports stated that risperidone is equivalent to haloperidol, we used half the dose of risperidone for comparison with haloperidol.

|

|

Received Sept. 5, 2004; revisions received Dec. 4, 2004, and May 17, 2005; accepted May 27, 2005. From the Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid; the Department of Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón; the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore; and the Department of Health Sciences, Universidad de Alcalá, Madrid. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Arango, Departamento de Psiquiatría, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, C/Ibiza, 43, 28009 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] (e-mail).The authors thank Brian Kirkpatrick, M.D., for his comments on a draft of the article.

1. Campan L, Lazorthes G: [The origin and success of neuroleptics.] Ann Anesthesiol Fr 1976; 17:1021–1024 (French)Medline, Google Scholar

2. Rifkin A, Quitkin F, Klein DF: Akinesia: a poorly recognized drug-induced extrapyramidal behavioral disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1975; 32:672–674Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Goldberg E: Akinesia, tardive dysmentia, and frontal lobe disorder in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1985; 11:255–263Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Lewander T: Neuroleptics and the neuroleptic-induced deficit syndrome. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994; 89(suppl 380):8-13Google Scholar

5. Awad AG: Subjective response to neuroleptics in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1993; 19:609–618Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Carpenter WT Jr, Heinrichs DW, Wagman AM: Deficit and nondeficit forms of schizophrenia: the concept. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:578–583Link, Google Scholar

7. Kirkpatrick B, Buchanan RW, McKenney PD, Alphs LD, Carpenter WT: The Schedule for the Deficit Syndrome: an instrument for research in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 1989; 30:119–124Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Tollefson GD, Sanger TM: Negative symptoms: a path analytic approach to a double-blind, placebo- and haloperidol-controlled clinical trial with olanzapine. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:466–474Link, Google Scholar

9. Möller HJ: The negative component in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1995; 91(suppl 388):11-14Google Scholar

10. Rosenheck R, Perlick D, Bingham S, Liu-Mares W, Collins J, Warren S, Leslie D, Allan E, Campbell EC, Caroff S, Corwin J, Davis L, Douyon R, Dunn L, Evans D, Frecska E, Grabowski J, Graeber D, Herz L, Kwon K, Lawson W, Mena F, Sheikh J, Smelson D, Smith-Gamble V (Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on the Cost-Effectiveness of Olanzapine): Effectiveness and cost of olanzapine and haloperidol in the treatment of schizophrenia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003; 290:2693–2702Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Tandon R, Goldman R, DeQuadro JR, Goldman M, Perez M, Jibson M: Positive and negative symptoms covary during clozapine treatment in schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res 1993; 27:341–347Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Miller D, Arndt S, Andreasen NC: Negative symptoms in antipsychotic-naive schizophrenics and the effect of haloperidol (abstract). Biol Psychiatry 1994; 35:746Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Lieberman JA, Safferman AZ, Pollack S, Szymanski S, Johns C, Howard A, Kronig M, Bookstein P, Kane JM: Clinical effects of clozapine in chronic schizophrenia: response to treatment and predictors of outcome. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1744–1752Link, Google Scholar

14. Peralta V, Cuesta MJ, Martinez-Larrea A, Serrano JF: Differentiating primary from secondary negative symptoms in schizophrenia: a study of neuroleptic-naive patients before and after treatment. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1461–1466Link, Google Scholar

15. Kirkpatrick B, Buchanan RW, Ross DE, Carpenter WT Jr: A separate disease within the syndrome of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:165–171Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Breier A, Buchanan RW, Kirkpatrick B, Davis OR, Irish D, Summerfelt A, Carpenter WT Jr: Effects of clozapine on positive and negative symptoms in outpatients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:20–26Link, Google Scholar

17. Buchanan RW, Breier A, Kirkpatrick B, Ball P, Carpenter WT Jr: Positive and negative symptom response to clozapine in schizophrenic patients with and without the deficit syndrome. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:751–760Link, Google Scholar

18. Supplementary Drugs and Other Substances. London, Pharmaceutical Press (Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain), 2002, p 1628Google Scholar

19. American Psychiatric Association: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154(April suppl)Google Scholar

20. Schotte A, Janssen PF, Megens AA, Leysen JE: Occupancy of central neurotransmitter receptors by risperidone, clozapine and haloperidol, measured ex vivo by quantitative autoradiography. Brain Res 1993; 631:191–202Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Kudo S, Takashi I: Pharmacokinetics of haloperidol. Clin Pharmacokinet 1999; 37:435–456Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. He H, Richardson JS: A pharmacological, pharmacokinetic and clinical overview of risperidone, a new antipsychotic that blocks serotonin 5-HT2 and dopamine D2 receptors. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1995; 10:19–30Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Simpson GM, Angus JWS: A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1970; 212:11–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Barnes TRE: A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry 1989; 154:672–676Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Kuenstler U, Juhnhold U, Knapp WH, Gertz HJ: Positive correlation between reduction of handwriting area and D2 dopamine receptor occupancy during treatment with neuroleptic drugs. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging 1999; 90:31–39Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Ventura J, Lukoff D, Nuechterlein KH: Appendix 1: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale Expanded Version (4.0) scales, anchor points, and administration manual. Int J Meth Psychiatr Res 1993; 3:227–243Google Scholar

27. Andreasen NC: Modified Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1984Google Scholar

28. Jaeger J, Bitter I, Czobor P, Volavka J: The measurement of subjective experience in schizophrenia: the Subjective Deficit Syndrome Scale. Compr Psychiatry 1990; 31:216–226Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Luria RE: The validity and reliability of the visual analogue mood scale. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:51–57Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Koehler K, Sauer H: Huber’s basic symptoms: another approach to negative psychopathology in schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry 1984; 25:174–182Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Remington G, Kapur S, Zipursky R: APA practice guideline for schizophrenia: risperidone equivalents (letter). Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1301–1302Link, Google Scholar