Increased Impulsivity Associated With Severity of Suicide Attempt History in Patients With Bipolar Disorder

Abstract

Background: Impulsivity is a prominent and measurable characteristic of bipolar disorder that can contribute to risk for suicidal behavior. The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship between impulsivity and severity of past suicidal behavior, a potential predictor of eventual suicide, in patients with bipolar disorder. METHOD: In bipolar disorder subjects with either a definite history of attempted suicide or no such history, impulsivity was assessed with both a questionnaire (Barratt Impulsiveness Scale) and behavioral laboratory performance measures (immediate memory/delayed memory tasks). Diagnosis was determined with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. Interviews of patients and review of records were used to determine the number of past suicide attempts and the medical severity of the most severe attempt. RESULTS: Subjects with a history of suicide attempts had more impulsive errors on the immediate memory task and had shorter response latencies, especially for impulsive responses. Impulsivity was highest in subjects with the most medically severe suicide attempts. Effects were not accounted for by presence of depression or mania at the time of testing. Barratt Impulsiveness Scale scores were numerically, but not significantly, higher in subjects with suicide attempts. A history of alcohol abuse was associated with greater probability of a suicide attempt. Multivariate analysis showed that ethanol abuse history and clinical state at the time of testing did not have a significant effect after impulsivity was taken into account. DISCUSSION: These results suggest that a history of severe suicidal behavior in patients with bipolar disorder is associated with impulsivity, manifested as a tendency toward rapid, unplanned responses.

Suicide is a potentially preventable cause of death in those with major affective disorders (1). A DSM-IV axis I diagnosis is present in about 90% of persons who commit suicide (2, 3). Suicide may be the cause of death in 5%–15% of patients with bipolar disorder, depending on how the population is defined (1). A recent 20-year study of 53,466 patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder found that 6% died by suicide during the study period (4). Suicide may be relatively common as a cause of death but is rare as a specific event. Effective monitoring of suicide risk therefore requires the identification of clinical characteristics that are associated with high risk. Severe suicide attempts can be disruptive and tragic in their own right and may be harbingers of eventual completed suicide (5). Severe suicide attempts appear to require depression or hopelessness combined with a factor that reduces inhibitions toward suicidal behavior (6–8). In a variety of clinical populations, impulsivity has been consistently reported to be higher in suicide attempters (8–13) or eventual completers (14) than in comparison subjects. Impulsivity is prominent in bipolar and related disorders (15–18), with standard questionnaire measures of impulsivity increased even during euthymia in bipolar disorder subjects (15). Yet, the relationship between impulsivity and suicidal behavior has not been investigated directly in bipolar disorder patients.

Impulsivity is a complex behavioral construct (19–24). Action without planning or reflection is central to most definitions of impulsivity. Thus, impulsivity appears to be associated with a failure of behavioral filtering processes outside of consciousness (25), with compromised ability to reflect on impending acts or to use knowledge and intelligence to guide behavior (26). Impulsive behavior, including aggression (27) and suicide attempts (7), differs from corresponding premeditated behavior by having an inappropriately short threshold for response, lack of reflection, lack of modulation, and lack of potential gain, leading potentially to dissociation between an action and its intent (28).

Studies of suicide and impulsivity have generally characterized impulsivity as a personality trait on the basis of questionnaire responses or have inferred it from characteristics of the index suicide attempt or from a history of impulsive aggression. Objective behavioral laboratory performance tests can provide a complementary method for measuring impulsivity that does not rely on recall or interpretation of past behavior. Certain types of commission errors on variants of the Continuous Performance Test (22, 29) have been shown to correlate with impulsive personality characteristics and risk for impulsive behavior (21, 22, 30). Horesh (31) reported that impulsive responses on a Continuous Performance Test variant differentiated suicide attempters from comparison subjects, but for the measure of impulsivity used, the rate of impulsive responses was extremely low (0%–4%)—not sensitive enough to determine quantitative relationships between impulsivity and suicidal behavior. More recently (32), we reported that impulsive laboratory performance was associated with history of suicide attempts in nonbipolar psychiatric patients, although there was no information about medical seriousness of attempts.

More people attempt than complete suicide, and suicide attempters and completers have different demographic and clinical characteristics. Characteristics associated with risk for eventual suicide can be identified by studying subjects who resemble suicide victims (33), such as subjects who carried out medically severe suicide attempts that required substantial medical treatment or that would have been lethal if rescue had not occurred (34). Similarly, severity of suicidal ideation at its worst was a robust predictor of eventual suicide in a longitudinal study (35). Patients with bipolar disorder who eventually completed suicide were more likely to have made an attempt during the previous 7 years (5). Therefore, history of severe suicide attempts may be an indicator of risk for eventual completed suicide, and objectively measurable characteristics of persons with previous severe suicidal behavior may be useful in identifying individuals at risk for eventual suicide.

We have investigated relationships between history of suicidal behavior and impulsivity in subjects with bipolar disorder. We used the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale questionnaire (19), which tends to measure impulsivity as a stable characteristic, as a self-report indicator of impulsivity and immediate memory/delayed memory tasks derived from the Continuous Performance Test (30) as behavioral laboratory measures of impulsivity. History of suicidal behavior was evaluated in terms of the number of previous attempts and the severity of the most severe attempt. Our hypothesis was that increased number and severity of suicide attempts would be associated with higher scores on the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale and with more impulsive errors on the immediate memory/delayed memory tasks.

Method

Subjects

Subjects with bipolar disorder were recruited from the inpatient clinical research unit at the Harris County Psychiatric Center or from the outpatient Neurobehavioral Laboratory and Clinic, University of Texas Mental Sciences Institute. The study was reviewed and approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects, the Institutional Review Board for the University of Texas Health Science Center, and affiliated hospitals. Before study-specific procedures were carried out, the study was thoroughly explained to prospective subjects, and written informed consent was obtained. Diagnosis was determined with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (36). Symptoms were assessed by using the change version of the Schedule for Affective Disorder and Schizophrenia (37). There were 48 subjects (17 men and 31 women) with usable data for suicide attempt history (positive or negative). At the time of assessment, 22 were manic (nine pure manic), 31 were depressed (18 pure depressive), 13 were in mixed states, and eight were not experiencing an episode of illness.

Assessment of Impulsivity

Behavioral laboratory impulsivity was measured by using immediate memory/delayed memory tasks derived from the Continuous Performance Test (30). Subjects were shown five-digit numbers on a computer screen, for 0.5 seconds, at 0.5-second intervals. For the immediate memory task, subjects were instructed to respond if a set of numbers matched the previous set. There are three outcomes: correct detections (matching sets are identified accurately), commission errors (sometimes called false alarms, where the subject responds to a set with 4 of the 5 digits correct), and random errors (subject responds to a set of five completely different numbers). The delayed memory task was similar except that, between sets of numbers to be matched, three distracters consisting of “12345” are shown for 0.5 sec at 0.5-sec intervals. We have reported that commission error rates were elevated in impulsive populations (30) and were correlated with impulsivity-related psychopathology (23), that increased commission errors were associated with use of alcohol (38) and cocaine (39), and that commission errors were increased in manic patients with bipolar disorder and correlated with mania ratings (15, 16). Results are presented for correct detections and commission errors; random errors never exceeded 5% and did not vary across any experimental groups.

The Barratt Impulsiveness Scale was used as a self-report assessment of impulsivity (19). It consists of 30 items measuring three aspects of impulsivity: attentional (rapid, unstable thoughts and lack of cognitive patience); motor (a tendency for impetuous action); and nonplanning (lack of future orientation) (19, 40). Barratt Impulsiveness Scale scores are elevated in interepisode bipolar disorder patients (15) and in those with substance abuse (41).

Measures of Suicidal Behavior

The number of attempts was confirmed by clinical records and interviews of subjects and significant others. It was scored as zero if there had been no attempt, one if there was one attempt, and two if there were more than one attempt.

Subjects were asked about the method used and the consequences (in terms of treatment, hospitalization, and medical sequelae) for each attempt. The most severe attempt was scored as “1” if definite medical treatment was required but the injury was not severe and the method would not have been expected to produce severe injury. The attempt was scored as “2” if there was injury requiring significant medical treatment, if there were permanent medical sequelae, or if the attempt was likely to cause severe injury or death. This was adapted from an earlier community-based study of suicide attempters (42). Scores were based on concordance of two independent raters who were not aware of subjects’ scores on impulsivity measures.

The median time elapsed between the most severe suicide attempt and the time of study was 48 months (25th to 75th percentile range=7–68 months). Time elapsed did not correlate significantly with impulsivity measures (for immediate memory task commission errors, r=0.061) and was not related significantly to severity of the most severe attempt (Kruskal Wallis H=0.18, p=0.67).

Data Analysis

The primary analyses used categorical measures of suicidal behavior as independent variables, and measures of impulsivity as dependent variables, in analyses of variance. First, we investigated comparisons of subjects with versus without a history of suicide attempts. Then, we compared subjects according to severity of the most severe suicide attempt. Post hoc comparisons used the Newman-Keuls test. Two-way analysis of variance was used to examine roles of affective state at the time of testing and history of substance abuse. Relationships between suicide variables and discrete characteristics were examined using chi-square analysis, with Yates correction if indicated, or Fisher’s exact test. Probabilities were two-tailed, and p<0.05 was the minimal criterion for statistical significance. Variables were tested for homogeneity of variance by using the Levene test and for normality of distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Data that departed significantly from normality of distribution or homogeneity of variance were analyzed nonparametrically. Logistic regression analysis (SAS version 8.2, Cary, N.C., SAS Institute) was used to determine the role of impulsivity-related and clinical characteristics in severity of suicide attempt history.

Results

Characteristics Associated With Suicide Attempt History

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Eight of 17 men and 16 of 31 women had attempted suicide (p=1.0, Fisher’s exact test). Attempters and nonattempters did not differ significantly in terms of age (mean=36.2 years [SD=11.7] and 35.4 years [SD=8.4], respectively), age at onset of illness (mean=16.2 years [SD=10.6] and 19.6 years [SD=8.7]), or educational attainment (mean=14.4 years [SD=3.0] and 13.3 years [SD=2.1]).

Attempters were more likely than nonattempters to have met criteria for ethanol abuse: 16 of 24 attempters and eight of 21 nonattempters had histories of ethanol abuse (p=0.05, Fisher’s exact test). The groups did not differ in substance abuse other than ethanol (12 of 23 attempters versus seven of 20 nonattempters (p=0.21, Fisher’s exact test).

Patients with a history of suicide attempts were more likely to be experiencing mixed states at the time of testing (three of 22 without history of attempts versus 10 of 24 with attempts) (p=0.05, Fisher’s exact test). Neither current pure depression (p=1.00, Fisher’s exact test) nor pure mania (p=0.30, Fisher’s exact test) at the time of testing was significantly related to a history of suicide attempts.

Impulsivity measures

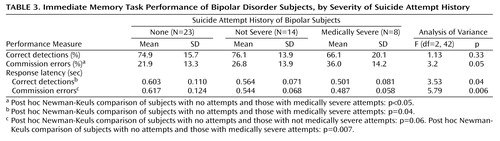

As summarized in Table 1, a history of suicide attempts was associated with a greater probability of impulsive responses on the immediate memory task and a shorter impulsive response latency. There were nonsignificant differences in the same direction for the delayed memory task. Barratt Impulsiveness Scale scores appeared higher in subjects who had attempted suicide, but these differences were not statistically significant.

Single versus multiple suicide attempts

Among subjects with suicide attempts, 12 had made one attempt, and 12 had made more than one (range=2–10). Patients with multiple and single attempts did not differ significantly with respect to Barratt Impulsiveness Scale scores, immediate memory/delayed memory task performance, age, or education.

Relationships to Severity of Suicide Attempt History

Subjects with no history of a suicide attempt, subjects whose most severe attempt was not medically severe, and subjects with medically severe suicide attempts did not differ significantly with respect to age, gender, age at onset of bipolar disorder, or educational attainment, as summarized in Table 2. A history of alcohol abuse, current mixed state, and current pure depressive state tended to be associated with severity of suicide attempt history.

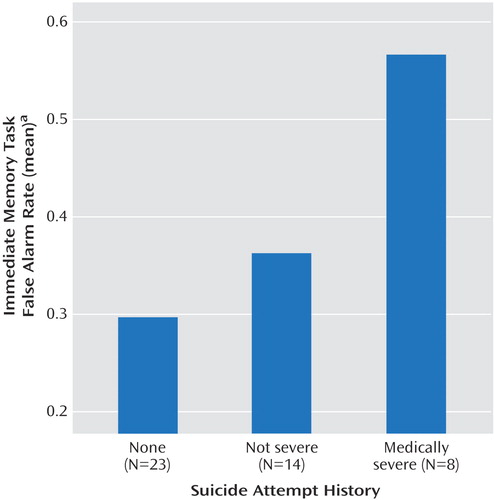

Memory Task Performance

Table 3 summarizes immediate memory task performance comparing subjects with no suicide attempts, subjects whose most severe attempt was not medically severe, and subjects whose most severe attempt was medically severe. With increasing severity of suicide attempt history, frequency of impulsive responses increased, and response latency diminished. Figure 1 shows that impulsive responses relative to correct detections were substantially increased in subjects with medically severe suicide attempts. The relationship with response latencies was stronger for impulsive responses (commission errors) than correct detections.

No relationships between suicide attempt severity and delayed memory task performance were statistically significant (data not shown). Qualitatively, effects resembled those of immediate memory task performance, as in Table 1.

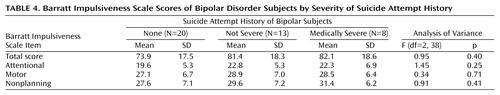

Barratt Impulsiveness Scale Scores

Barratt Impulsiveness Scale scores appeared somewhat elevated in subjects with suicide attempts regardless of severity, but analysis of variance was not significant (Table 4).

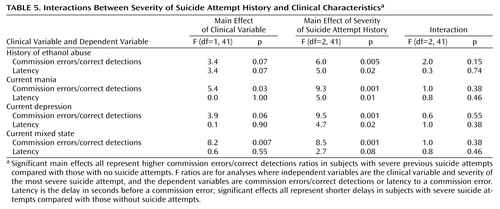

Interactions Between Clinical and Impulsivity Variables

We carried out two-way analyses of variance for main effects and interactions of clinical state, ethanol abuse, and severity of suicide attempt history. It was necessary to carry out separate analyses for each clinical variable because combined analyses had some cells with inadequate numbers of members. We considered variables as having relationships with severity of suicide attempt history in analyses in which p<0.10. We also included mania, since mania is associated with increased immediate memory task commission errors and 22 of 48 subjects were in mixed or pure manic states. The results are summarized in Table 5. In each case, severity of the suicide attempt history had a significant main effect. In addition, current pure manic and mixed states had significant main effects on commission errors/correct detections, and there were nearly significant effects of ethanol abuse and pure depression. There were no significant interactions between clinical variables and severity of suicide attempt history. The effect on commission error response latency was limited to medically severe suicide attempts, with no significant main effect or significant interaction involving any other variable. Statistical power is a consideration with this sample size, but interactions did not even approach statistical significance. Therefore, even when clinical characteristics such as a current manic or mixed state were associated with impulsive immediate memory task performance, they did not account for the finding that subjects with medically severe suicide attempts had immediate memory task impulsive response rates that were significantly higher than subjects without such histories.

In order to determine the relative roles of measures of impulsivity and of clinical characteristics in distinguishing subjects with respect to severity of past suicide attempts, we conducted a stepwise logistic regression analysis using variables associated with significant univariate effects on suicide attempt severity. Only immediate memory task commission errors/correct detections (χ2=6.75, df=1, p=0.009) and latency to a commission error (χ2=15.5, df=1, p<0.0001) contributed significantly, while current depressed, mixed or manic state, or history of alcohol abuse, did not. The model predicted 86.8% of cases correctly. This analysis was preliminary because of the relatively small number of subjects, but it provides consistent evidence that neither current clinical state nor history of alcohol abuse appeared to account for the relationships between immediate memory task performance and history of suicidal behavior.

Discussion

In this group of subjects with bipolar disorder, a history of suicide attempts was associated with impulsive responses on an immediate memory task, especially for subjects with medically severe attempts. The significantly shorter latency to an impulsive response in subjects with histories of severe suicidal behavior further supports a relationship between susceptibility to impulsivity and risk for suicidal behavior. These results are consistent with previous reports associating impulsivity with past or subsequent suicidal behavior (43) and provide the first such evidence using an objective measure of impulsivity in bipolar disorder.

Impulsivity may be related to clinical state (16) or to intellect or educational attainment (19). In this study, educational attainment was not significantly related to presence, frequency, or severity of past suicidal behavior. Subjects were in a variety of affective states (euthymic, mixed, manic, or depressive) when they were tested. While being in a mixed or pure depressive state was associated with a tendency toward greater severity of past suicidal behavior, clinical state at the time of testing did not account for the relationships between suicidal behavior history and impulsive immediate memory task performance. In no case had the most severe suicide attempt occurred during the subject’s current episode.

Impulsivity and Suicidal Behavior

There is conflicting information about the specificity of any relationship between impulsivity and severe suicidality. Impulsivity may be associated with nonlethal suicide attempts or suicide gestures (44). Strength of the wish to die is related to planning, which would appear to suggest lack of impulsivity in more lethal suicide attempts. Impulsivity as a character trait, however, was associated with severe suicide attempts (45) or completed suicide (14) in patients with affective disorders. Impulsivity distinguished suicidal inpatients from nonsuicidal inpatients and comparison subjects (46), and suicidal from nonsuicidal depressed inpatients (47). Suicidal intent correlated with impulsivity even after controlling for aggression (48). Among suicide attempters, impulsivity predicted eventual completed suicide more than 12 months later (14). These findings are consistent with models for suicidal behavior that require some disinhibitory factor even in predominantly premeditated attempts, suggesting that impulsivity increases risk when combined with depression (7, 49, 50).

In a case/control study, we found about 25% of medically severe suicide attempts to have been carried out without reflection (51). Compared with premeditated suicide attempts, impulsive attempts were associated with milder depressive symptoms (not significantly different from community comparison subjects) but hopelessness comparable to premeditated attempts in which depression was prominent. Compared with premeditated attempters, impulsive attempters had less expectation to die but greater use of a violent method, consistent with the mismatch between actions and intentions that characterizes impulsivity (51).

Measures of impulsivity or of impulsive-aggression may complement hopelessness or severe suicidal ideation as predictors of lifetime risk for severe suicidal behavior. These results suggest that impulsivity may be associated with greater likelihood of severe suicidal behavior in bipolar disorder. Interactions between impulsivity and other risk factors for suicide, including substance abuse, require further investigation.

Role of Alcohol Abuse

Alcohol abuse is associated with increased risk for suicidal behavior and with increased impulsivity. It is possible that alcohol abuse acts as a mediator variable, being responsible for the effect of impulsivity on suicidal behavior. The data reported here, however, do not support such a relationship. First, the effect of alcohol abuse appeared weaker than that of impulsivity. Second, alcohol abuse and suicide attempt severity had noninteracting main effects on immediate memory task performance (Table 5). Third, immediate memory task performance made a highly significant contribution to a logistic regression analysis classifying subjects according to severity of past suicidal behavior, whereas alcohol abuse did not.

Differential Relationships to Impulsivity Measures

Impulsive responses on the immediate memory/delayed memory tasks have been reported to reflect real-world impulsivity in subjects with disruptive behavior disorders (22) and their parents (21), impulsive aggression (30), and bipolar disorder (16), and to be increased by moderate doses of ethanol (52). We recently reported that nonbipolar psychiatric patients with histories of suicide attempts had more impulsive errors on the immediate memory task than did those without suicide attempts (32). In the current analyses, the relationship between increased laboratory-measured impulsivity and past suicidal behavior was independent of effects of current clinical state or of substance abuse. The delayed memory task requires that the target digits be remembered while distracters are presented. The fact that performance on the immediate memory task was related more strongly than the delayed memory task to past suicidal behavior suggests that this history was related to deficits in attention or in the ability to inhibit rapid responses more than in working memory.

Barratt Impulsiveness Scale scores were not significantly elevated in subjects with suicide attempts or associated with severity of previous attempts. This is consistent with earlier reports in which a history of suicide attempts was associated with increased impulsive continuous performance task responses but not with increased Barratt Impulsiveness Scale scores (31, 32). Barratt Impulsiveness Scale scores were numerically higher in subjects with histories of suicide attempts, suggesting that in a larger group of subjects there might be a significant relationship between Barratt Impulsiveness Scale scores and history of attempted suicide, but not its severity (Table 4).

These results suggest that measures of impulsivity are differentially related to history of suicidal behavior. It might appear surprising that the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, considered a stable trait measure of impulsivity, did not seem as strongly related to past suicidal behavior as was performance on the immediate memory task, which sometimes appears to be state dependent (16). These tests measure different aspects of behavior related to impulsivity (22, 53). The Barratt Impulsiveness Scale relies on the subject’s recall of behavior and attitudes. The immediate memory task measures impulsivity as expressed by rapid, unplanned responses, made before the subject has been able to assess the stimulus adequately (21). The relationship between severity of suicidal behavior and response latency further supports the relationship between suicide risk and a tendency toward rapid, unplanned responses. Commission error rates on immediate memory/delayed memory tasks may be a measure of potential for impulsive behavior or behavioral dyscontrol (28). Impulsive performance on immediate memory/delayed memory tasks in the absence of mania, as also reported in patients with bipolar disorder and substance or alcohol abuse (54), may therefore be an indicator of severe behavioral risk in bipolar disorder. Performance on immediate memory/delayed memory tasks, especially the immediate memory task, may be an objectively measurable characteristic that is related to long-term risk of severe suicidal behavior.

Limitations

The group of subjects studied was relatively small (N=48) and had a preponderance of women, whereas bipolar disorder generally appears to have an equal gender ratio, and completed suicide occurs more often in men than in women. Severity of suicide attempts was assessed retrospectively. Subjects were in a variety of affective states (manic, depressed, mixed, or euthymic) when tested.

Conclusions

The present data suggest that impulsivity, as reflected by a tendency toward rapid, unplanned responses on an immediate memory task, is a measurable characteristic of subjects with severe previous suicidal behavior. This effect does not appear to be dependent on effects of alcohol abuse or on clinical state at the time of testing. Performance on the immediate memory task may therefore be an objectively measurable characteristic that is related to long-term risk of severe suicidal behavior. The specificity of its association with risk for suicide, and the value of measuring change in impulsivity in potentially suicidal patients, remain to be established prospectively.

|

|

|

|

|

Received April 14, 2004; revision received July 30, 2004; accepted Sept. 9, 2004. From the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Mental Sciences Institute, Harris County Psychiatric Hospital, University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Swann, Department of Psychiatry, University of Texas Medical School at Houston, 1300 Moursund, Rm. 270, Houston, TX 77030; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by the Pat R. Rutherford, Jr. Chair in Psychiatry and by NIH grants AA-12046 (Dr. Dougherty) and DA-08425 (Dr. Moeller). The authors thank Glen Colton, Psy.D., Saba Abutaseh, and the staffs of Unit 2C of the Harris County Psychiatric Center and the Neurobehavioral Research Clinic for their assistance with this study.

Figure 1. Laboratory Performance Impulsivity in Bipolar Disorder Subjects by Severity of Suicide Attempt Historya

aCommission errors as a proportion of correct detections on the immediate memory task. Significant differences (per post hoc Newman-Keuls tests) seen between patients with medically severe suicide attempts and those with not severe attempts (p=0.005) and no attempts (p=0.001).

1. Jamison KR: Suicide and bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61(suppl 9):47–51Google Scholar

2. Bronisch T, Wittchen HU: Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: comorbidity with depression, anxiety disorders, and substance abuse disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1994; 244:93–98Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Fawcett J: Treating impulsivity and anxiety in the suicidal patient. Ann NY Acad Sci 2001; 932:94–102Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Hoyer EH, Olesen AV, Mortensen PB: Suicide risk in patients hospitalised because of an affective disorder: a follow-up study, 1973–1993. J Affect Disord 2004; 78:209–217Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Tsai SY, Kuo CJ, Chen CC, Lee HC: Risk factors for completed suicide in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63:469–476Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Himmelhoch JM: What destroys our restraints against suicide? J Clin Psychiatry 1988; 49(Sept suppl):46–52Google Scholar

7. Mann JJ, Waternaux C, Haas GL, Malone KM: Toward a clinical model of suicidal behavior in psychiatric patients. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:181–189Abstract, Google Scholar

8. Pezawas L, Stamenkovic M, Jagsch R, Ackerl S, Putz C, Stelzer B, Moffat RR, Schindler S, Aschauer H, Kasper S: A longitudinal view of triggers and thresholds of suicidal behavior in depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63:866–873Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Crumley FE: Adolescent suicide attempts. JAMA 1979; 241:2404–2407Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Gut-Fayand A, Dervaux A, Olie JP, Loo H, Poirier MF, Krebs MO: Substance abuse and suicidality in schizophrenia: a common risk factor linked to impulsivity. Psychiatry Res. 2001; 102:65–72Google Scholar

11. Koller G, Preuss UW, Bottlender M, Wenzel K, Soyka M: Impulsivity and aggression as predictors of suicide attempts in alcoholics. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2002; 252:155–160Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. O’Boyle M, Brandon EA: Suicide attempts, substance abuse, and personality. J Subst Abuse Treat 1998; 15:353–356Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Lejoyeux M, Arbaretaz M, McLoughlin M, Ades J: Impulse control disorders and depression. J Nerv Ment Dis 2002; 190:310–314Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Maser JD, Akiskal HS, Schettler P, Scheftner W, Mueller T, Endicott J, Solomon D, Clayton P: Can temperament identify affectively ill patients who engage in lethal or near-lethal suicidal behavior? a 14-year prospective study. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2002; 32:10–32Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Swann AC, Anderson JC, Dougherty DM, Moeller FG: Measurement of inter-episode impulsivity in bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res 2001; 101:195–197Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Swann AC, Pazzaglia P, Nicholls A, Dougherty DM, Moeller FG: Impulsivity and phase of illness in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 2003; 73:105–111Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Anderson KJ, Revelle W: Impulsivity and time of day: is rate of change in arousal a function of impulsivity? J Pers Soc Psychol 1994; 67:334–344Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Allen TJ, Moeller FG, Rhoades HM, Cherek DR: Impulsivity and history of drug dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend 1998; 50:137–145Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Barratt ES, Patton JH: Impulsivity: cognitive, behavioral, and psychophysiological correlates, in Biological Basis of Sensation-Seeking, Impulsivity, and Anxiety. Edited by Zuckerman M. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1983, pp 77–122Google Scholar

20. Moeller FG, Barratt ES, Dougherty DM, Schmitz JM, Swann AC: Psychiatric aspects of impulsivity. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1783–1793Link, Google Scholar

21. Swann AC, Bjork JM, Moeller FG, Dougherty DM: Two models of impulsivity: relationship to personality traits and psychopathology. Biol Psychiatry 2002; 51:988–994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Dougherty DM, Bjork JM, Harper RA, Marsh DM, Moeller FG, Mathias CW, Swann AC: Behavioral impulsivity paradigms: a comparison in hospitalized adolescents with disruptive behavior disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2003; 44:1145–1157Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Marsh DM, Dougherty DM, Mathias CW, Moeller FG, Hicks LR: Comparison of women with high and low trait impulsivity using laboratory impulsivity models of response-disinhibition and reward-choice. J Pers Individ Diff 2002; 33:1291–1310Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Evenden J: Impulsivity: a discussion of clinical and experimental findings. J Psychopharmacol 1999; 13:180–192Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Bechara A, Damasio H, Tranel D, Damasio AR: Deciding advantageously before knowing the advantageous strategy. Science 1997; 275:1293–1295Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Barratt ES, Stanford MS, Felthous AR, Kent TA: The effects of phenytoin on impulsive and premeditated aggression: a controlled study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1997; 17:341–349Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Virkkunen M, Linnoila M: Brain serotonin, type II alcoholism and impulsive violence. J Stud Alcohol Suppl 1993; 11:163–169Medline, Google Scholar

28. Barratt ES, Stanford MS, Dowdy L, Liebman MJ, Kent TA: Impulsive and premeditated aggression: a factor analysis of self-reported acts. Psychiatry Res 1999; 86:163–173Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Halperin JM, Wolf LE, Pascualvaca DM, Newcorn JH, Healey JM, O’Brien JD, Morganstein A, Young JG: Differential assessment of attention and impulsivity in children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1988; 27:326–329Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Dougherty DM, Bjork JM, Marsh DM, Moeller FG: A comparison between adults with conduct disorder and normal controls on a continuous performance test: differences in impulsive response characteristics. Psychol Rec 2000; 50:203–219Crossref, Google Scholar

31. Horesh N: Self-report vs computerized measures of impulsivity as a correlate of suicidal behavior. Crisis 2001; 22:27–31Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Dougherty DM, Mathias CW, Marsh DM, Papageorgiou TD, Swann AC, Moeller FG: Laboratory-measured behavioral impulsivity relates to suicide attempt history. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2004; 34:374–385Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Lester D, Beck AT, Trexler L: Extrapolation from attempted suicides to completed suicides. J Abnorm Psychol 1975; 84:563–566Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. O’Carroll PW, Crosby A, Mercy JA, Lee RK, Simon TR: Interviewing suicide “decedents”: a fourth strategy for risk factor assessment. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2001; 32:3–6Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Beck AT, Brown GK, Steer RA: Psychometric characteristics of the Scale for Suicide Ideation with psychiatric outpatients. Behav Res Ther 1997; 35:1039–1046Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-P), version 2. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1996Google Scholar

37. Spitzer RL, Endicott J: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Change Version, 3rd ed. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1978Google Scholar

38. Dougherty DM, Moeller FG, Steinberg JL, Marsh DM, Hines SE, Bjork JM: Alcohol increases commission error rates for a continuous performance test. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1999; 23:1342–1351Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Moeller FG, Dougherty DM, Barratt ES, Schmitz JM, Swann AC, Grabowski J: The impact of impulsivity on cocaine use and retention in treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat 2001; 21:193–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES: Factor structure of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. J Clin Psychol 1995; 51:768–774Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Moeller FG, Dougherty D, Barratt ES, Oderinde V, Mathias CW, Harper RA, Swann A: Increased impulsivity in cocaine dependent subjects independent of antisocial personality disorder and aggression. Drug Alcohol Depend 2002; 68:105–111Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Potter LB, Kresnow M, Powell KE, O’Carroll PW, Lee RK, Frankowski RF, Swann AC, Bayer TL, Bautista MH, Briscoe MG: Identification of nearly fatal suicide attempts: Self-Inflicted Injury Severity Form. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1998; 28:174–186Medline, Google Scholar

43. Soloff PH, Lynch KG, Kelly TM, Malone KM, Mann JJ: Characteristics of suicide attempts of patients with major depressive episode and borderline personality disorder: a comparative study. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:601–608Link, Google Scholar

44. Baca-Garcia E, Diaz-Sastre C, Basurte E, Prieto R, Ceverino A, Saiz-Ruiz J, de Leon J: A prospective study of the paradoxical relationship between impulsivity and lethality of suicide attempts. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62:560–564Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Beautrais AL, Joyce PR, Mulder RT: Personality traits and cognitive styles as risk factors for serious suicide attempts among young people. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1999; 29:37–47Medline, Google Scholar

46. Horesh N, Rolnick T, Iancu I, Dannon P, Lepkifker E, Apter A, Kotler M: Anger, impulsivity and suicide risk. Psychother Psychosom 1997; 66:92–96Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Corruble E, Damy C, Guelfi JD: Impulsivity: a relevant dimension in depression regarding suicide attempts? J Affect Disord 1999; 53:211–215Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Horesh N, Gothelf D, Ofek H, Weizman T, Apter A: Impulsivity as a correlate of suicidal behavior in adolescent psychiatric inpatients. Crisis 1999; 20:8–14Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Apter A, Plutchik R, van Praag HM: Anxiety, impulsivity and depressed mood in relation to suicidal and violent behavior. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1993; 87:1–5Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50. Baumeister RF: Suicide as escape from self. Psychol Rev 1990; 97:90–113Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51. Simon TR, Swann AC, Powell KE, Potter LB, Kresnow M, O’Carroll PW: Characteristics of impulsive suicide attempts and attempters. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2001; 32(suppl 1):30–41Google Scholar

52. Dougherty DM, Marsh DM, Moeller FG, Chokshi RV, Rosen VC: Effects of moderate and high doses of alcohol on attention, impulsivity, discriminability, and response bias in immediate and delayed memory task performance. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2000; 24:1702–1711Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53. Dougherty DM, Marsh DM, Mathias CW: Immediate and delayed memory tasks: a computerized behavioral measure of memory, attention, and impulsivity. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput 2002; 34:391–398Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54. Swann AC, Dougherty DM, Pazzaglia PJ, Pham M, Moeller FG: Impulsivity: a link between bipolar disorder and substance abuse. Bipolar Disord 2004; 6:204–212Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar