Family History of Suicide Among Suicide Victims

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The aim was to compare the rates of suicide in family members of suicide victims and comparison subjects who died of other causes. METHOD: The Swedish cause of death register identified all suicides in subjects born between 1949 and 1969 (N=8,396). The comparison group comprised persons of the same age who died of other causes (N=7,568). First-degree relatives of the suicide victims (N=33,173) and comparison subjects (N=28,945) were identified. RESULTS: Among families of the suicide victims there were 287 suicides, representing 9.4% of all deaths in family members. Among comparison families there were 120 suicides, 4.6% of all deaths. The difference was significant. Previous psychiatric care and suicide in a family member predicted suicide in the logistic regression model. CONCLUSIONS: The rate of suicide was twice as high in families of suicide victims as in comparison families. A family history of suicide predicted suicide independent of severe mental disorder.

Attempted and completed suicides among first-degree relatives of suicide victims have been described in several retrospective studies of adolescents and young adults who committed suicide (1–5). In previous reports (2, 3) one of us noted that 38% of young suicide victims had a parent or sibling who attempted suicide. A family history of completed suicide was found in 5%. Suicide in family members appears to be a predisposing factor for suicide irrespective of psychopathology (6). Genetic transmission has been emphasized (6–9); however, an environmental effect has also been demonstrated (9). These studies were based on relatively small, selected study groups.

Can familial clustering also be observed in the general population? To answer this question we compared the rates of suicide in family members of suicide victims and comparison subjects who died of other causes.

Method

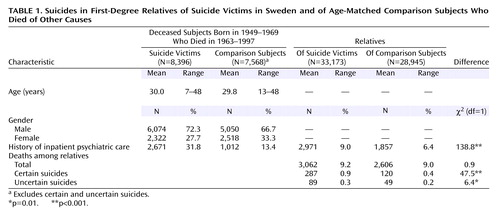

The national cause of death register (Statistics Sweden) was used to identify all suicides in people born between 1949 and 1969. Deaths occurring between 1963 and 1997 were analyzed. The suicide sample thus comprised 8,396 subjects. For each suicide victim, we attempted to identify a comparison subject of the same age (±5 years) who died of a cause other than suicide in the same year as the suicide victim. The comparison group was somewhat smaller because comparison subjects could not be found for all suicide subjects. Uncertain suicides were excluded, yielding 7,568 comparison subjects. As males were more prevalent among the suicide victims than among comparison subjects (Table 1), gender was included in a further analysis. The median age was 29 years in both groups.

We chose 1949 as the starting point because reliable family register data were lacking before this date. Family members were identified for the suicide victims (N=33,173) and comparison subjects (N=28,945). Numbers of deaths, especially suicides in family members, were collected. Suicides occurring both before and after the index death were included. Previous psychiatric hospitalization, as recorded in the national inpatient register, was used as a proxy marker of serious mental disorder.

The numbers of first-degree family members for the suicide victims and comparison subjects were similar. The ages of family members were analyzed for fathers, mothers, siblings, and children separately and did not differ significantly between the suicide victims and comparison subjects.

A backward stepwise logistic regression (conditional) was performed to study the specific effects of a family history of suicide and of psychiatric care in the first-degree relatives of the suicide victims and comparison subjects.

Results

In the families of the suicide victims, 287 certain suicides occurred; 120 suicides occurred in the families of the comparison subjects (Table 1). These represented 9.4% versus 4.6% of all deaths in family members (χ2=47.5, df=1, p<0.001). Table 1 shows further that the uncertain suicides (E980–989 in ICD-9 and Y10–34 in ICD-10) were also more common in the family members of suicide victims. The total numbers of deaths from all causes were similar in the family members of suicide victims and comparison subjects. Of the certain suicides among relatives of the suicide victims, 1.7% (five of 287) involved suicide by two relatives in the same family; 0.8% of the suicides (one of 120) among relatives of the comparison subjects involved multiple members of the same family; the difference was not significant.

Gender was not a significant factor in the logistic regression model; the odds ratio was 1.06, with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 0.85–1.31. This variable was thus excluded in the second step. Previous psychiatric care was the strongest predictor (odds ratio=3.88, 95% CI=3.09–4.86), and a family history of suicide also increased the risk (odds ratio=1.97, 95% CI=1.59–2.44). In the second step, previous psychiatric care (odds ratio=3.87, 95% CI=3.09–4.85) and suicide in a family member (odds ratio=1.98, 95% CI=1.58–2.45) still showed increased risk. The model was considered appropriate, as no significant differences were observed between steps 1 and 2. No interaction between the two variables in step 2 could be shown.

Discussion

We believe this to be the first record linkage study to examine familial clustering of suicide in a general population sample of suicide victims and comparison subjects who died of other causes. Results from a recent Danish study that used living comparison subjects point in the same direction (10). The present study was feasible because of the high quality of the national register data. The samples were appropriate for the analyses performed. Family size and family age were controlled for.

The total mortality rate was not significantly higher among relatives of suicide victims. Suicide seemed to be a marginal addition to the deaths by other causes.

The main finding of the present study is that the rate of suicide was significantly higher in the families of suicide victims than in the families of comparison subjects. Nevertheless, the strongest risk factor for suicide in the families was mental disorder, defined by previous psychiatric inpatient care. The strong connection between suicide and mental disorder is well established (1–8). But still, a family history of suicide was a significant risk factor independent of severe mental disorder.

The mechanism for familial clustering was not elucidated with the present methods. However, as family history of suicide was an independent factor, a mechanism other than genetic transmission of mental disorder is likely. Clustering may be related to, for example, aggressive behavior or impulsiveness in families (1). Contagion and social influences have also been discussed (9). Whatever the mechanism for familial transmission of suicidal behavior may be, caution is justified in the aftermath of suicide. Supportive interventions may be indicated for the families of suicide victims.

|

Received Sept. 10, 2002; revision received Feb. 4, 2003; accepted Feb. 12, 2003. From the Karolinska Institutet, Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Section for Psychiatry, St. Goran’s Hospital and Karolinska Hospital, Stockholm. Address reprint requests to Dr. Runeson, Karolinska Institutet, Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Section for Psychiatry, St. Goran’s Hospital, S-112 81 Stockholm, Sweden; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by the Söderström-Königska Foundation (Swedish Society of Medicine). The authors thank Anna Wiklund, B.A., and Dag Tidemalm, M.A., for statistical support and Margda Waern, M.D., Ph.D., for aid with the language.

1. Brent DA, Bridge J, Johnson BA, Connolly J: Suicidal behavior runs in families. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:1145–1152Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Runeson B, Beskow J, Waern M: The suicidal process in suicides among young people. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1996; 93:35–42Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Runeson B: History of suicidal behaviour in the families of young suicides. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1998; 98:497–501Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Gould M, Fischer P, Parides M, Flory M, Shaffer D: Psychosocial risk factors of child and adolescent completed suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:1155–1162Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Shafii M, Carrigan S, Whittinghill JR, Derrick A: Psychological autopsy of completed suicide in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 1985; 142:1061–1064Link, Google Scholar

6. Tsuang MT: Risk of suicide in the relatives of schizophrenics, maniacs, depressives, and controls. J Clin Psychiatry 1983; 44:396–400Medline, Google Scholar

7. Juel-Nielsen N, Videbech T: A twin study of suicide. Acta Genet Med Gemellol (Roma) 1970; 19:307–310Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Roy A, Segal NL: Suicidal behavior in twins: a replication. J Affect Disord 2001; 66:71–74Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Fu Q, Heath AC, Bucholz KK, Nelson EC, Glowinski AL, Goldberg J, Lyons MJ, Tsuang MT, Jacob T, True MR, Eisen SA: A twin study of genetic and environmental influences on suicidality in men. Psychol Med 2002; 32:11–24Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Qin P, Agerbo E, Mortensen PB: Suicide risk in relation to family history of completed suicide and psychiatric disorders: a nested case-control study based on longitudinal registers. Lancet 2002; 360:1126–1130Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar