Psychiatric Resident Conceptualizations of Mood and Affect Within the Mental Status Examination

Abstract

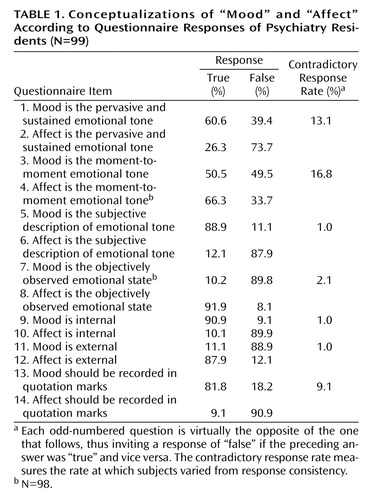

OBJECTIVE: To explore the ways in which psychiatry residents conceptualize the terms “mood” and “affect,” a 14-item questionnaire was sent to residency programs in New York. METHOD: The questions consisted of possible definitions of mood and affect; all questions required a “true” or “false” response. Residents (N=99) were asked how they viewed mood and affect from a temporal perspective (i.e., sustained versus momentary) and in terms of an objective-subjective (or external-internal) dichotomy. RESULTS: There were inconsistencies in the temporal view of mood (said to be sustained by 60.6% and momentary by 50.5%) and affect (“pervasive” by 26.3% and “momentary” by 66.3%). Residents overwhelmingly defined mood as being subjective and internal and affect as being objective and external. CONCLUSIONS: If mood and affect are to be viewed from both perspectives, psychiatrists must infer the enduring internal emotional tone (mood) of a patient over an entire interview.

A key element of the mental status examination is the description of the emotional state, which is traditionally designated as mood and affect (1–4).

The distinction between mood and affect is not always as clear as one might expect. There are two dimensions used to describe these facets of emotional tone. One is temporal, i.e., there can be a transient or a sustained state. The other dimension is subjective/internal versus objective/external. Mood is generally said to be both sustained and internal; affect, on the other hand, is momentary and external.

Textbook definitions often deviate from this approach and may vary by eliminating one or the other dimension. For example, Tasman et al. (1) emphasize the temporal dimension for mood and both dimensions for affect: “…patient’s mood is a pervasive … state” and “affect is the way one modulates and conveys one’s feeling state from moment to moment.”

This is also essentially the approach taken by Kaplan and Sadock (2).

On the other hand, Hales and Yudofsky (3) define mood as solely temporal (“Mood is the sustained feeling tone that prevails over time”) and affect as solely objective (“affective expression” is defined as a “range of expression of feeling tones” to be recorded as observations).

Stoudemire (4) sees mood as temporal and internal; affect is the way mood is “expressed or exuded” (external).

The inherent confusion in this area has been captured best by Trzepacz and Baker (5):

Mood [is] the patient’s subjective description of his or her feeling state…affect the objectively observable manifestations of the feeling state(s). However, some psychiatrists rely not on this subjective/objective dichotomy but rather on the aspect of changeability to differentiate mood from affect. In that paradigm, mood is a consistent, sustained feeling state, whereas affect is the moment-to-moment expression of feelings.

Although these authors suggest that “both of these conventions can be applied,” there may be inconsistencies in practice because of possible incompatibility between the temporal and objective/subjective perspectives. Should an internal emotional tone always be thought of as sustained?

To assess prevailing definitions of mood and affect among trainees, a questionnaire was administered to psychiatric residents from eight programs in New York City.

Method

A questionnaire with 14 true/false questions was administered. Ninety-nine residents chose to participate.

Answers were totaled across programs. Questions 1 through 12 were designed to demonstrate how the individual resident defined mood or affect by presenting specific aspects of their definitions and asking whether these were true or false. Two additional questions dealt with the manner of documenting mood and affect in the mental status examination. Questions 1–4 addressed the temporal perspective of mood and affect; questions 5–12 related to the objective/external versus subjective/internal approach; questions 13–14 inquired about the use of quotation marks to record mood or affect.

Results

Residents demonstrated inconsistencies in their views of mood and affect along the temporal continuum (Table 1). Although mood was defined as pervasive and sustained by 60.6% of trainees, it was also said to be moment-to-moment by 50.5%. Affect was seen as pervasive by only 26.3% and as momentary by 66.3%.

The 14 questions can be viewed as seven pairs, virtually inviting a “true” response to a question if the preceding response was “false” and vice versa. Thus, inconsistency is reflected in the difference between these opposite answers to successive questions in the pair (contradictory response rate, as seen in Table 1). The degree to which residents strayed from consistency was much greater for temporally oriented questions (1 versus 2; 3 versus 4) than for the subjective/objective or internal/external descriptors.

There were sharp distinctions between mood and affect along the nontemporal dimension. Residents almost universally defined mood as subjective (88.9%) and internal (90.9%), while viewing affect as objective (91.9%) and external (87.9%).

In keeping with these latter views, residents endorsed the use of quotation marks for mood 81.8% of the time and for affect only 9.1%.

Discussion

Only a small majority of residents defined mood as sustained, and a majority also saw mood as moment-to-moment, an inconsistency. Although affect was defined as moment-to-moment by most residents, there were still many (more than 25%) who said that affect is sustained. Residents appear to be less focused on the temporal aspect of emotional tone than on the concept of mood as subjective/internal and affect as objective/external.

By limiting the concepts of mood and affect to an internal versus external dichotomy, residents may have become reliant upon the use of direct quotes to record a patient’s mood, as the data suggest. This implies that the patient alone can report the internal emotional state. Thus, one might see mood described, in quotes, as “I feel fine,” when, in fact, the patient may be melancholic. Relying solely on patient verbal responses about mood may be analogous to accepting all responses to such questions as “Do you hear voices?” For example, the documentation of perceptual changes in the mental status examination might be limited to “I do not hear voices” rather than presenting a more complete picture such as “the patient appears to be responding to external stimuli.” This broader manner of observation, when applied to emotional tone, may more accurately reflect the mood, i.e., the emotion that is sensed over the course of the entire interview.

The varied definitions of mood and affect in the literature undoubtedly mirror the teaching of terminology to medical students and residents. The confusion engendered may relate to the complexity inherent in the view that mood is sustained and subjective and that affect is the reverse of both. Trainees learn to use these measures of emotional tone from faculty, more senior residents, and from the literature. In the face of the varied extant definitions, there may be a tendency to simplify the approach to this part of the mental status examination, ignoring some of the distinctions.

How can the two dimensions of mood and affect be reconciled? Affect is external, objective, visible emotional tone. It is also the moment-to-moment measure, which may be labile or constricted, congruent or not with expressed ideas, and may be varied during any interview. Mood, on the other hand, is an internal, subjective, and sustained emotional state and should be reported as such.

As the results of this study demonstrate, it is unclear how this aspect of patient evaluation is stressed in residency programs. Training programs may need to consider assessing the approaches of their own residents and faculty in defining mood and affect. However, this should be preceded by a larger study, based on live or videotaped interviews, which might extend these findings to actual practice.

|

Received Aug. 6, 2002; revision received March 7, 2003; accepted March 17, 2003. From the Department of Psychiatry, Beth Israel Medical Center. Address reprint requests to Dr. Serby, Department of Psychiatry, Beth Israel Medical Center, 16th St. at First Ave., New York, NY 10003.

1. Tasman A, Kay J, Lieberman JA: Psychiatry. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1997, p 481Google Scholar

2. Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ: Synopsis of Psychiatry, 8th ed. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1998, pp 250–251Google Scholar

3. Hales RE, Yudofsky SC: Essentials of Clinical Psychiatry. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 1999, pp 109–110Google Scholar

4. Stoudemire A: Clinical Psychiatry for Medical Students. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1998, p 30Google Scholar

5. Trzepacz PT, Baker RW: The Psychiatric Mental Status Examination. New York, Oxford University Press, 1993, p 39Google Scholar