Does Patient Cognition Predict Time Off From Work After Life-Threatening Accidents?

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Accidental injuries are frequent and their socioeconomic consequences enormous. The present study aimed to identify predictors of the number of days of leave taken in a consecutively selected group of accident victims who sustained severe, mostly life-threatening physical trauma. METHOD: One hundred patients with severe accidental injuries who were referred to a trauma surgeons’ intensive care unit were followed up for 12 months. The main outcome measure was the number of days of leave taken that were attributable to the accident 1 year after the trauma. RESULTS: Multiple regression analysis explained 30% of the variance in the number of days of leave taken that were attributable to the accident. Factors contributing to the predictive model were injury severity, type of accident and, most significantly, the patients’ subjective self-assessment of accident severity and of their abilities to cope with the accident and its job-related consequences. Patients who perceived the severity of their accident as relatively low and judged their coping abilities as high took a mean 121 days of leave compared to 287 days of leave taken by those who perceived the trauma as relatively severe and were less optimistic regarding their coping abilities. A two-factor analysis of variance showed that patient perceptions of accident severity and their appraisal of their coping abilities made independent contributions to the predicted amount of leave taken. CONCLUSIONS: In severely injured accident victims, leave taken because of the accident depended to a considerable degree on the patients’ accident-related self-assessment.

In 1866, the British surgeon John Eric Erichsen first described a syndrome consisting of cognitive impairments and psychosomatic symptoms that occurred in survivors of railway accidents (1). He reported that this condition was frequently associated with a deteriorating business sense. Erichsen’s “railway spine” is regarded as one of the first accounts of the social consequences of accidental injuries. More recently, it has been pointed out that in addition to physical impairment and psychiatric morbidity, accidental injuries inevitably cause social disability, affecting work, leisure, and family life (2). However, the determinants of time taken off work because of accidental injuries remain unclear. When we take into account the frequency of accidents worldwide and their effect on society in terms of the loss of manpower through the temporary and permanent inability to work, the scarcity of published research on this issue is surprising.

Some studies on the social consequences of accidents have focused on litigation and “accident neurosis” (3–5). Other authors have reported that psychological morbidity after injury have compromised the patients’ return to work (6, 7). Nevertheless, little is known to date about the relationships between injury severity, patients’ psychological reactions, and their appraisals regarding the accident and its consequences on one hand and the duration of leave because of the accident on the other hand. It has been shown in patients after myocardial infarction that optimistic beliefs concerning their illness predicted an earlier return to work (8). In accident victims, a higher extent of the patients’ perceived control over convalescence seems to be associated with a shorter hospital stay (9).

The present study aimed to identify predictors of the number of days of leave taken in a group of accident victims who sustained severe, mostly life-threatening physical trauma but no severe head injuries. To study the effect of the accident selectively, we collected a group of patients who were free from preexisting mental disturbances. We hypothesized that objective accident-related measures and psychosocial factors, such as the patients’ early psychological reactions and accident-related cognitions, would be equally important predictors of time taken off work.

Method

Participants and Study Design

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Zurich. All participants had sustained accidental injuries that caused a life-threatening or critical condition requiring their referral to the intensive care unit of the trauma department at the University Hospital of Zurich (10–12). The University Hospital of Zurich accepts regional referrals of all kinds of accident victims. In addition, as our center is a recognized trauma center, patients with severe and complicated accidental injuries are referred from all over Switzerland and southern Germany. An Injury Severity Score (13) of 10 or more and a Glasgow Coma Scale (14) score of 9 or more were required, thus excluding all patients with severe head injuries. Furthermore, the patients had to be 18–70 years of age and able to take part in an extensive interview within 1 month of the accident regarding both their clinical condition and fluency in German. All interviews were conducted by an experienced internist who had been involved in research for a number of years and was thoroughly trained in traumatic stress research. Patients suffering from any serious somatic illness or who had been under psychiatric treatment immediately before the accident and/or those who showed marked clinical signs or symptoms of mental disturbances that were obviously unrelated to the accident were excluded. Patients for whom a history of mental disorder had been elicited during the interview were discussed in detail with the first author before a final decision was made regarding their inclusion. Sixteen patients were excluded for this reason. In addition, all patients who sustained their injuries as a result of a suicide attempt or from a physical attack were excluded from the study.

During a recruitment period of 18 months, all patients in the intensive care unit were consecutively screened; 135 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria. After the study was completely described to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained from 121 patients; 14 (10.4%) refused to participate. Follow-up interviews were performed at 12 months, ±3 weeks, after the trauma. Fifteen (12.4%) of the 121 patients were lost to the study during the follow-up period: one patient committed suicide, one returned to her country of origin, and 13 refused to participate in the follow-up. Thus, 106 patients participated in the 1-year follow-up. The 14 patients who refused to participate in the study did not differ significantly from our group regarding sex, age, or Injury Severity Score and Glasgow Coma Scale score. However, significantly more work-related accidents were found among the refusers (refusers: seven [50%], group: 13 [12.3%]) (p<0.01, Fisher’s exact test). The 15 dropouts did not differ significantly from the 106 participants regarding sociodemographic characteristics or accident-related variables. Finally, three patients were supported by a pension, one patient was a homemaker, and two patients with incomplete data had to be excluded from the analyses regarding fitness for work. Thus, all further analyses in this article were performed on a final group of 100 patients.

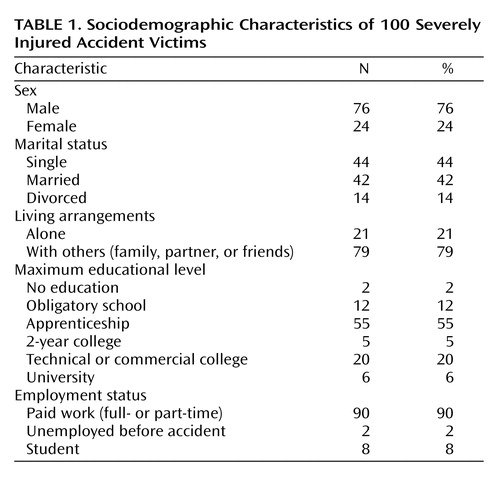

Sociodemographic characteristics of the group are presented in Table 1 (mean for age was 36.8 years, SD=12.5). Traffic accidents were most frequent (61 patients), followed by severe sports or leisure accidents (20 patients), accidents in the workplace (13 patients), and household accidents (six patients). No significant differences in injury severity (Injury Severity Score mean values) were found among these four types of accidents: traffic: 22.2 (SD=10.4), sports or leisure: 23.6 (SD=12.2), workplace: 20.8 (SD=6.1), and household: 19.8 (SD=6.0) (F=0.31, df=3, 96, p=0.82). According to the surgeons’ files, 38 patients suffered from retrograde amnesia; 42 patients sustained a traumatic brain injury, i.e., they had objectively reported loss of consciousness and/or pathological findings on cranial computerized tomography. A significant association was found between retrograde amnesia and traumatic brain injury (Pearson χ2=17.6, df=1, p<0.001).

Initial assessments took place shortly after the patients had been transferred from the intensive care unit to the regular trauma surgeons’ ward. The mean number of days between the accident and interview was 13.5 (SD=6.6, range=3–29).

Measures

The Injury Severity Score (13) permits an evaluation of the gravity of injuries by a trauma surgeon: every area of the body concerned is given a score (1=minimum, 6=fatal injury). The scores for the three most severely injured areas of the body are squared and then summed, producing a maximum score of 75. Patients with a score of 10 or more are generally considered severely injured. The Glasgow Coma Scale (14) is an observer-rated scale for the clinical appraisal of the gravity of a coma after injury to the skull and brain. Patients with severe traumatic brain injuries generally have a score under 9.

In the semistructured interviews, sociodemographic data, including a detailed work record and information about the accidents were collected. The patients were asked to make a subjective appraisal of the severity of the accident by using a Likert scale, ranging from 1=very low to 5=very high. Furthermore, the patients were asked to assess their abilities to cope with the accident and its job-related consequences using a Likert scale, ranging from 1=very poor to 5=very good.

Posttraumatic psychological symptoms were assessed by using the Impact of Event Scale (15), a 15-item self-rating questionnaire comprising two subscales (intrusion and avoidance) with high reliability and validity as a screening instrument for posttraumatic stress disorder (16, 17). The SCL-90-R (18, 19) was used to cover a broad range of psychopathological symptoms.

Time taken off work was calculated as the number of days of leave taken from the time of the injury (including time in the hospital), with a week off work equaling seven days of leave. When the subjects returned to work only part-time if they were previously full-time employees, the days on which they worked on a reduced level were added to the total days of leave on a prorated basis.

Predictive Model and Statistical Analyses

For the establishment of a stable regression model predicting the number of days of sick leave attributable to the accident, we selected nine potential predictor variables. In order to be suitable for the development of a screening instrument, all variables had to be assessed shortly after the accident and in a short time. Injury Severity scores and types of accident were chosen as objective accident-related variables. Gender and age were selected as potential pretraumatic predictors. The Impact of Event Scale intrusion subscale allows for a quick assessment of posttraumatic psychological symptoms (seven items regarding intrusive recollections of the trauma). The patients’ self-assessments were represented in the model by their subjective perception of accident severity and their appraisal of their ability to cope with the accident and its consequences.

Data were analyzed by using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (20). Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to assess correlations between the target variable of leave taken from work because of the accident (assessed at the 12-month follow-up) and all potential predictor variables. Linear multiple regression analysis was used for the prediction of the total number of days of leave taken that were attributable to the accident during the first 12 months. To enter the type of accident (traffic, workplace, sports or leisure, or household) as a predictor into the multiple regression analysis, this categorical variable was converted into a set of three new variables so that a deviation contrast resulted. Accordingly, the effect of each accident category was compared to the mean effect of all accident categories. Since there was one new variable for each degree of freedom, one accident category (household) had to be omitted in the regression analysis (21).

Results

Descriptive Data

Surgical and psychosocial assessments administered shortly after the accident are presented in Table 2. The mean Injury Severity Score of 22.1 indicates that patients were severely injured. Nevertheless, the Glasgow Coma Scale mean score of 14.4 was close to the maximum of 15 that indicates full consciousness. The average length of stay at the university hospital was 30.1 days. After the acute surgical treatment phase, 50 patients were hospitalized in a rehabilitation center with an average additional stay of 76.3 days. The mean total number of inpatient days was 68.2 (SD=78.4, range=4–365). The duration of the total of inpatient days did not differ significantly across the four types of accidents (F=0.41, df=3, 96, p=0.75). The mean total number of days of leave taken was 202.

Leave time taken correlated significantly with all measures of psychopathology: the General Symptomatic Index of the SCL-90-R (r=0.22, p<0.05), the Impact of Event Scale intrusion scale (r=0.34, p<0.001), and the Impact of Event Scale avoidance scale (r=0.24, p<0.05). Significant intercorrelations were found between these psychological parameters (r=0.54–0.69, p<0.001). Therefore, it seemed appropriate to select only one of these psychopathological variables to be entered in the multivariate analysis. We chose the Impact of Event Scale intrusion subscale because after a traumatic event, reexperiencing symptoms tends to develop earlier than depression; also, the Impact of Event Scale intrusion score showed the highest correlation with the number of days of leave taken.

Prediction of Leave Taken

Table 3 shows bivariate correlations between predictor variables and the dependent variable “days of leave taken,” as well as the predictor variables’ intercorrelations. It is noteworthy that the patients’ self-assessments of accident severity and their coping abilities did not correlate with objective measures of injury severity (the Injury Severity Score). Overall, no high intercorrelations were found between the predictor variables.

In multiple regression analysis, 30% of the variance of the number of days of leave taken could be explained by means of our nine predictor variables. Out of these, four variables contributed significantly to the predictive model: injury severity (p<0.05), accidents related to sports or leisure (p<0.05), patients’ appraisals of accident severity (p<0.001), and patients’ appraisals of their abilities to cope with the accident and its job-related consequences (p<0.05) (Table 4).

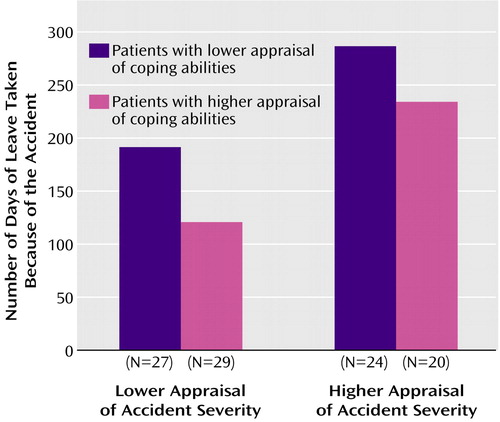

As the most powerful predictors in our model, the patients’ self-assessments were analyzed further. Cross-tabulation of patients according to their appraisals of accident severity (higher or lower, median split) and abilities to cope with the accident and its job-related consequences (higher or lower, median split) yielded an almost equal distribution among the four subgroups. Accordingly, no significant association was found between the two appraisal variables (Pearson’s χ2=0.40, df=1, p=0.53). In the subgroup of patients who perceived the severity of their accident as relatively low, those who were very optimistic with regard to their future functional health took a mean 121 days of leave (SD=96), compared to 191 days (SD=114) by the less optimistic patients. For those who perceived their accident as relatively severe, the optimistic patients had a mean of 234 days of sick leave (SD=116), compared to 287 days (SD=98) for the less optimistic (Figure 1). A two-factorial analysis of variance showed that the patients’ self-assessments regarding accident severity (F=23.61, df=1, 96, p<0.001) and their future coping abilities (F=8.28, df=1, 96, p<0.01) each made significant contributions to the prediction of leave time taken off work, with no significant interaction between the two variables (F=0.17, df=1, 96, p=0.68).

In order to control this last analysis for the other two significant predictors of our multiple regression analysis, namely the Injury Severity Score and accidents occurring during sports or leisure time, a two-factorial analysis of variance and chi-square tests were performed. The Injury Severity Score did not differ, depending on the patients’ appraisals of accident severity (F=0.29, df=1, 96, p=0.59) or on the patients’ appraisals of their coping abilities (F=1.90, df=1, 96, p=0.17). There was also no significant interaction between these two cognitive variables in relation to Injury Severity Score (F=0.89, df=1, 96, p=0.35). Patients who had accidents during sports or leisure time were equally distributed among the two groups of patients with different appraisals of accident severity (Pearson’s χ2=0.01, df=1, p=0.92). However, accidents during sports or leisure time were overrepresented in patients who rated their future coping abilities higher (Pearson’s χ2=6.76, df=1, p<0.01) (Table 5). In other words, the influence of the patients’ self-assessments of accident severity and future functional health on days of leave taken was confounded by the type of accident but not by injury severity.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study that used a representative group of severely injured accident victims to investigate the determinants of the number of days of leave taken because of the accident. Our aim was to collect as homogeneous a group as possible, with patients free from mental disturbances that were attributable to severe head injuries. The mean Injury Severity Score (22.1) and the Glasgow Coma Scale score (14.4) in our group indicated that this goal was achieved. Furthermore, the patients were excluded from the study if they showed any signs of previous psychological problems. The exclusion of patients who had attempted suicide or had been exposed to a physical assault further contributed to the homogeneity of the group.

Contrary to other groups that were drawn from accident victims seeking treatment for their posttraumatic psychological problems (22–24) or claiming compensation for personal injury (7), our group was collected consecutively, with the intensive care unit of the traumatology department of the University Hospital of Zurich as the single source. Only 10% of the eligible patients refused to participate in our study, an unusually low refusal rate compared with those in other published studies of accident victims (25–27). The dropout rate was also low. Comparative analyses of refusers and dropouts showed that our final group was representative of the population we intended to study. With regard to sociodemographic variables, our group was typical of groups of accident victims in general. Patients in this study were predominantly young men; marital status, living arrangements, educational level, and employment status corresponded to the sex and age distribution of admissions to our trauma surgeons’ intensive care unit. However, generalizability of our data to trauma populations with different socioeconomic and ethnic composition remains unclear.

This study has a number of limitations. First, the patients had to be excluded from the study if they did not speak German sufficiently. Proficiency in the official language of a country is a strong determinant of social integration; according to our clinical experience, patients with poor social integration have greater-than-average difficulties in dealing with the consequences of their accident. Therefore, in future studies, patients whose mother tongue is other than the country’s official language should be included by using interpreters. Second, the study did not include the full spectrum of accident victims, so inferences can only be made about those with severe accidental injuries. Also, certain types of injury are more likely to be related to unfitness for work, independent of the formal measure of the Injury Severity Score. For instance, patients with spinal cord injuries (Injury Severity Score=9) were not included in our study unless they had sustained additional injuries. Third, the patients’ self-assessments were not evaluated by using standardized instruments, but rather simple Likert scales. While the questions used have not been comprehensively validated, they certainly have face validity and their simplicity allows their use in routine clinical work. Furthermore, our results clearly support the predictive validity of the questions used. Finally, from our study design, one cannot be confident that the relationship between the attribution questions and outcome was a direct one, although this seems likely. Responses to these questions correlated with SCL-90-R scores (General Symptomatic Index by appraisal of accident severity [r=0.22, p<0.05] and by appraisal of coping abilities [r=–0.29, p<0.01]). As with other patient groups in the general hospital, a considerable proportion of our patients were likely to have been depressed, and depression in turn was likely to influence attributions (28, 29). However, despite each self-assessment correlating with the General Symptomatic Index, they were independent of each other. If they were both manifestations of depression, surely this would not be the case. Also, patients’ reports may have been influenced by the recency of the traumatic event, pain medication, and sleep medication. Nevertheless, whether the attributions studied are directly relevant to outcome or represent epiphenomena of depression or other posttraumatic psychopathology, they appear to be markers of outcome which, because of their simplicity, are potentially useful clinically and for research.

The key finding of this study was that patients’ appraisals of the severity of their accident and their ability to cope with the accident and its job-related consequences made substantial contributions to the duration of their time off work, independent of the severity of the injury. In addition, those who sustained their injuries during sports or leisure pursuits were likely to return to work sooner than those with injuries from other sorts of accidents, irrespective of the objective severity of the injuries.

The modest contribution of injury severity (assessed by the Injury Severity Score) to days of sick leave may have been due at least in part to the selection in this study of only patients with severe injuries. Had patients with mild or moderate injuries been included (thus covering the full range of Injury Severity Scores), the Injury Severity Score might have been a more powerful predictor of time taken off work. It is also noteworthy that, contrary to previous reports (6, 7), patients’ time taken off work was not independently predicted by their Impact of Event Scale scores. At the univariate level, Impact of Event Scale score correlated significantly with the number of days of leave taken; we assumed that in the multivariate analysis, the predictive power of the Impact of Event Scale score was suppressed by the patients’ appraisal variables, which each showed significant univariate correlations with Impact of Event Scale intrusion scores (Table 3).

In the present study, the strongest predictors of time taken off work were the patients’ self-assessments of accident severity and of their ability to cope. That each of these was apparently independent of the objective severity of injury is consistent with other work on patient appraisal of illness (28, 29). Cornes identified “psychological problems” as an important predictor of time taken off work because of accidental injuries (7) but without specifying these psychological problems in greater detail. In another study, objective medical ratings of loss of earning capacity were reported not to be predictive of overall occupational or psychosocial adjustment (30).

Patients who sustained their injuries during sports or leisure pursuits resumed work earlier than those whose accidents had other causes. To our knowledge, this finding has not been reported previously, although other authors have investigated samples of patients with different types of accidents (31–33). Several factors may contribute to this finding. First, patients in this group were more positive in their appraisals of their coping abilities than patients with other types of injury. Second, and possibly related to the first factor, people who have sustained injuries during activities that they freely choose to pursue are less likely to blame others for their accidents than those who were injured at work or in traffic accidents. It is possible that those injured during sports activities perceive such injuries as risks they choose to take, whereas work or traffic accidents are unlikely to be viewed in this light. Attributing blame to others has been associated in a variety of situations with unfavorable outcomes, although their influence on the outcome of accepting blame oneself has been less consistent (28). Third, individuals who have been physically active might be expected to recover more rapidly than other people from their injuries, although the duration of hospitalization did not differ significantly across the types of accident.

The influence of patients’ self-assessments on the number of days of leave taken that were attributable to the accident was not just statistically significant but makes a remarkable difference from a clinical and economic perspective, too. While Injury Severity Scores did not differ significantly among the four subgroups formed based on patient self-assessments, time taken off work varied between 4 and 9 months (Figure 1). Clearly, the results of this study could have numerous important clinical and therapeutic consequences, if they can be replicated in future work. First, attention to the cause of the trauma might assist in identifying subgroups of patients more likely than others to have longer time off work. Second, asking patients two brief and easily understandable questions may yield important information about key factors influencing the time to return to work. Third, our results suggest that an important focus for clinicians involved in the aftercare of patients with traumatic injuries should be to support and enhance their patients’ physical and psychological resources to cope with the accident and its sequelae. Finally, where a patient’s appraisals are pessimistic or negative, these are likely to be amenable to change. Under such circumstances, interventions might be helpful that aim to modify attributions, such as antidepressant treatment (if depression is present and is likely to have influenced the attributions) or cognitive behavior therapy. It has recently been reported that after myocardial infarction, therapeutically induced positive changes of illness perception were correlated with a faster return to work (34). The preventive effect of such interventions in accident victims, given at an early stage of recovery, and particularly the extent to which they could reduce the time to return to work, will need to be examined in randomized controlled trials.

|

|

|

|

|

Presented at the Third World Conference of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, Melbourne, Australia, March 16–19, 2000; the 23rd European Conference on Psychosomatic Research, Oslo, Norway, June 17–21, 2000; the 16th annual meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, San Antonio, Tex., Nov. 16–19, 2000; and the Seventh European Conference on Traumatic Stress, Edinburgh, U.K., May 26–29, 2001. Received Dec. 14, 2001; revision received Aug. 19, 2002; accepted Feb. 25, 2003. From the Psychiatric Department and the Department of Psychosocial Medicine, University Hospital, Zurich, Switzerland; and the Division of Neurosciences and Psychological Medicine, Imperial College School of Medicine, West Middlesex Hospital, Isleworth, Middlesex, U.K. Address reprint requests to Dr. Schnyder, Psychiatric Department, University Hospital, Culmannstrasse 8, 8091 Zurich, Switzerland; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (project number 32-43640.95). The authors thank Claus Buddeberg, Jasmin Donati, Edgar Heim, Christel Nigg, and Otmar Trentz for their contributions to this study.

Figure 1. Relation of Self-Appraisal of Accident Severity and Coping Abilities to Number of Days of Leave Taken Because of the Accident for 100 Severely Injured Accident Victims

1. Erichsen JE: On Railway and Other Injuries of the Nervous System. London, Walton & Maberly, 1866Google Scholar

2. Mayou R: Psychiatric aspects of road traffic accidents. Int Rev Psychiatry 1992; 4:45–54Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Parker N: Accident litigants with neurotic symptoms. Med J Aust 1977; 2:318–322Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Thompson GN: Post-traumatic psychoneurosis—a statistical survey. Am J Psychiatry 1965; 121:1043–1049Link, Google Scholar

5. Tarsh MJ, Royston C: A follow-up study of accident neurosis. Br J Psychiatry 1985; 146:18–25Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Michaels AJ, Michaels CE, Moon CH, Zimmerman MA, Peterson C, Rodriguez JL: Psychosocial factors limit outcomes after trauma. J Trauma 1998; 44:644–648Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Cornes P: Return to work of road accident victims claiming compensation for personal injury. Injury 1992; 23:256–260Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Petrie KJ, Weinman J, Sharpe N, Buckley J: Role of patients’ view of their illness in predicting return to work and functioning after myocardial infarction: longitudinal study. Br Med J 1996; 312:1191–1194Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Frey D, Rogner O: The relevance of psychological factors in the convalescence of accident patients, in Issues in Contemporary German Social Psychology: History, Theories and Application. Edited by Semin GR, Krahé B. London, Sage Publications, 1987, pp 241–257Google Scholar

10. Schnyder U, Mörgeli H, Nigg C, Klaghofer R, Renner N, Trentz O, Buddeberg C: Early psychological reactions to severe injuries. Crit Care Med 2000; 28:86–92Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Schnyder U, Moergeli H, Klaghofer R, Buddeberg C: Incidence and prediction of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in severely injured accident victims. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:594–599Link, Google Scholar

12. Schnyder U, Moergeli H, Trentz O, Klaghofer R, Buddeberg C: Prediction of psychiatric morbidity in severely injured accident victims at one-year follow-up. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 164:653–656Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Baker SP, O’Neill B: The Injury Severity Score: an update. J Trauma 1976; 16:882–885Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Teasdale G, Jennett B: Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness: a practical scale. Lancet 1974; 2:81–84Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Horowitz MJ, Wilner N, Alvarez W: Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med 1979; 41:209–218Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Ferring D, Filipp S-H: Teststatistische Überprüfung der Impact of Event-Skala: Befunde zu Reliabilität und Stabilität. Diagnostica 1994; 40:344–362Google Scholar

17. McFall ME, Smith DE, Roszell DK, Tarver DJ, Malas KL: Convergent validity of measures of PTSD in Vietnam combat veterans. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:645–648Link, Google Scholar

18. Derogatis LR: SCL-90-R: Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual, II. Towson, Md, Clinical Psychometric Research, 1983Google Scholar

19. Franke G: SCL-90-R: Die Symptomcheckliste von Derogatis—Deutsche Version—Manual. Göttingen, Germany, Beltz Test, 1995Google Scholar

20. SPSS 8.0 Syntax Reference Guide. Chicago, SPSS, 1997Google Scholar

21. Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS: Using Multivariate Statistics. New York, HarperCollins, 1996Google Scholar

22. Kuch K, Cox BJ, Evans RJ, Shulman I: Phobias, panic and pain in 55 survivors of road vehicle accidents. J Anxiety Disord 1994; 8:181–187Crossref, Google Scholar

23. Hickling EJ, Blanchard EB: Post-traumatic stress disorder and motor vehicle accidents. J Anxiety Disord 1992; 6:285–291Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Blanchard EB, Hickling EJ, Taylor AE, Loos WR, Gerardi RJ: Psychological morbidity associated with motor vehicle accidents. Behav Res Ther 1994; 32:283–290Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Green MM, McFarlane AC, Hunter CE, Griggs WM: Undiagnosed post-traumatic stress disorder following motor vehicle accidents. Med J Aust 1993; 159:529–534Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Blanchard EB, Hickling EJ, Taylor AE, Loos WR: Psychiatric morbidity associated with motor vehicle accidents. J Nerv Ment Dis 1995; 183:495–504Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Ursano RJ, Fullerton CS, Epstein RS, Crowley B, Kao T-C, Vance K, Craig KJ, Dougall AL, Baum A: Acute and chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in motor vehicle accident victims. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:589–595Abstract, Google Scholar

28. Sensky T: Causal attributions in physical illness. J Psychosom Res 1997; 43:565–573Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Sensky T: Patients’ reactions to illness: cognitive factors determine responses and are amenable to treatment. Br Med J 1990; 300:622–623Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Lee PW, Ho ES, Tsang AK, Cheng JC, Leung PC, Cheng YH, Lieh Mak F: Psychosocial adjustment of victims of occupational hand injuries. Soc Sci Med 1985; 20:493–497Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Feinstein A, Dolan R: Predictors of post-traumatic stress disorder following physical trauma: an examination of the stressor criterion. Psychol Med 1991; 21:85–91Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Malt U: The long-term psychiatric consequences of accidental injury: a longitudinal study of 107 adults. Br J Psychiatry 1988; 153:810–818Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Shalev AY, Peri T, Canetti L, Schreiber S: Predictors of PTSD in injured trauma survivors: a prospective study. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:219–225Link, Google Scholar

34. Petrie KJ, Cameron LD, Ellis CJ, Buick D, Weinman J: Changing illness perceptions after myocardial infarction: an early intervention randomized controlled trial. Psychosom Med 2002; 64:580–586Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar