Relationship of the Use of Adjunctive Pharmacological Agents to Symptoms and Level of Function in Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Adjunctive pharmacological agents are extensively used in the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. This cross-sectional study examined the prevalence of the use of adjunctive agents, the extent to which their use conforms with Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) recommendations for adjunctive pharmacological treatment and the relationship of conformance with treatment recommendations to demographic and clinical variables and to symptoms and level of function. METHOD: Outpatients with schizophrenia (N=344) underwent an extensive interview, and their medical records were reviewed. Data on demographic and clinical characteristics, medications, and role functioning were collected. RESULTS: More than two-thirds of the outpatients received antiparkinsonian agents, and 50% received an adjunctive agent other than an antiparkinsonian agent. Fifty-four (15.7%) outpatients received two or more nonantiparkinsonian adjunctive agents. Rates of conformance with the PORT treatment recommendations for the use of adjunctive agents ranged from 49% to 65%, depending on the type of agent. Ethnicity and diagnosis were the only two patient characteristics that were consistently related to conformance with PORT treatment recommendations. The treatment recommendation for adjunctive mood stabilizers was the only recommendation for which conformance was related to multiple measures of patients’ symptoms and level of function. CONCLUSIONS: Adjunctive agents are widely used in the pharmacological treatment of patients with schizophrenia, but there is a limited relationship between use of these agents in conformance with treatment recommendations and measures of symptoms and level of function. Longitudinal, prospective studies are needed to demonstrate the clinical utility of adjunctive agents.

Patients with schizophrenia are commonly treated with multiple medications, including adjunctive antiparkinsonian agents, antidepressants, antianxiety agents, β blockers, and mood stabilizers. The indications for these agents include antipsychotic-induced extrapyramidal side effects; co-occurring symptoms of depression, anxiety, hostility, and mania; and residual positive psychotic symptoms. Although adjunctive pharmacotherapy is a common practice, other than research on the use of antiparkinsonian agents for extrapyramidal side effects, there is limited empirical evidence supporting the efficacy of these interventions (1, 2). Moreover, there is little information regarding the patient and/or system-of-care characteristics that are associated with the use of adjunctive agents or whether the use of adjunctive agents is related to patient outcome in actual clinical practice.

The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) project conducted an extensive review of all studies investigating the use of adjunctive pharmacotherapies (1). The review led to the development of three treatment recommendations for the use of adjunctive agents in patients with schizophrenia (2). The three recommendations cover 1) the use of antiparkinsonian agents for the treatment of extrapyramidal side effects; 2) the use of benzodiazepines, β blockers, carbamazepine, and lithium for the treatment of anxiety, hostility, and manic-like symptoms and the use of antidepressants for depressive symptoms; and 3) the use of benzodiazepines, β blockers, and mood stabilizers for treatment-resistant positive symptoms.

The current study was designed to examine 1) the rate of conformance to the PORT recommendations for adjunctive pharmacotherapy, 2) the relationship of treatment recommendation conformance to demographic and clinical characteristics, and 3) the relationship of treatment recommendation conformance to measures of patients’ symptoms and level of function.

Method

Sample

The PORT project sampling procedures are described in detail elsewhere (3). Briefly, inpatient and outpatient and urban and rural treatment sites in two states were identified and asked to participate in the project. At each treatment site, patients were eligible for study participation if they 1) had a presumptive diagnosis of either schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, 2) could speak English, 3) were 18 years of age or older, and 4) were legally competent. Inpatient subjects were also required to have spent at least one night in the hospital and live within a specified geographic region. Patients who met these eligibility criteria were asked to undergo a survey interview and to give permission for a review of their medical records. The data for the present study were derived from subjects who were recruited only from outpatient treatment sites. A total of 1,017 outpatients met initial eligibility criteria. Of those, 584 subjects agreed to have their names released to the study, 550 met a more detailed eligibility assessment, and 440 (43.3% of the initial group of eligible subjects) underwent the study assessments. All subjects provided written informed consent before study entry. They were interviewed between December 1994 and March 1996.

The following additional inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied to arrive at the final subject group for the current study. Patients without a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder in the medical record (N=27) and subjects more than 64 years old (N=34) were excluded from the study. The latter exclusion criterion was added because pharmacotherapy practices may differ for elderly patients. Thus, 379 (86.1%) of the 440 outpatients who underwent the PORT study assessments were eligible for the present study.

Patient Assessments

Two data collection instruments were used for this project: 1) the PORT mental health survey, a 90-minute client interview, and 2) the PORT outpatient record review. The mental health survey is largely based on the Quality of Life Interview (4) and also contains the alcohol and drug CAGE questions (5) and selected items from the Hopkins Symptom Checklist–90 (6). The survey includes items on demographic characteristics, social and family relationships, living arrangements, daily activities and functioning, employment, financial resources, legal issues, health status, service use, patients’ knowledge about their illness and its treatment, life satisfaction, symptoms, medication side effects, and alcohol and drug use. The outpatient record review provides information on the patient’s psychiatric and medical history and diagnoses, health services utilization, treatment plan, current medications, and family contacts and services. Information about use of the following classes of adjunctive medications was recorded in the record review: 1) antiparkinsonian agents; 2) antidepressants; 3) anxiolytics/hypnotics; 4) β blockers, e.g., propranolol; and 5) mood stabilizers.

Treatment Recommendations

The PORT treatment recommendations are based on an extensive review of the treatment literature and expert opinion (1, 2). There are three treatment recommendations for the use of adjunctive agents in the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia. In the current study, we examined the treatment recommendations for the use of adjunctive agents in the pharmacological treatment of extrapyramidal side effects, persistent affective symptoms (i.e., anxiety, depressive, hostility, or manic-like symptoms), and persistent positive symptoms. We restricted our examination of the treatment recommendation for persistent affective symptoms to the use of adjunctive antidepressants for depression and adjunctive antianxiety agents for anxiety, since there were insufficient data to evaluate the use of β blockers for hostility symptoms and mood stabilizers for manic-like symptoms. We restricted our evaluation of the treatment recommendation for persistent positive symptoms to the use of mood stabilizers, since there were insufficient data to evaluate the use of benzodiazepines or β blockers for these symptoms. The modified treatment recommendations, conformance criteria, and data sources used to document conformance are listed in Appendix 1.

Medication Variables

The PORT outpatient record review was the source for data on the type, dosage, and route of administration of antipsychotic and adjunctive medications. The types of medication included all conventional antipsychotics and the two new-generation antipsychotics clozapine and risperidone. Data collection occurred before the marketing of either olanzapine or quetiapine. Patients were categorized as using a “conventional antipsychotic only” if they were treated only with a conventional antipsychotic and, similarly, as using a “new-generation antipsychotic only” if they were treated only with either clozapine or risperidone. The average daily antipsychotic dose was calculated by multiplying the unit dose of the antipsychotic medication by the number of daily units of medication prescribed. If more than one antipsychotic was prescribed for a patient, then the average daily dose was calculated for each medication, and the total average dose was calculated by summing the individual average antipsychotic doses. The average daily antipsychotic doses were converted to chlorpromazine equivalents per day to allow them to be combined and compared across antipsychotic types and classes (7–11).

Demographic and Clinical Variables

The following variables were used to evaluate the influence of patient, geographic, and treatment characteristics on conformance: age, gender, ethnicity (white versus nonwhite; because there were too few Hispanic and Asian subjects for these groups to be analyzed separately, these subjects were included with the African American subjects in the nonwhite group), state (A or B), locale (urban or rural), diagnosis (schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder), duration of illness, presence of substance abuse (alcohol or drug abuse), and psychiatric hospitalization during the past year (yes or no).

The PORT mental health survey was the source of data on age, gender, ethnicity, duration of illness, state, and locale. The PORT outpatient record review was the source of data on diagnosis and psychiatric hospitalization during the past year. Data on current alcohol or drug abuse were obtained from the mental health survey and the outpatient record review CAGE items and items on substance use, history of substance abuse treatment, and current substance abuse treatment.

Symptom and Level-of-Function Measures

The following symptom and functioning variables were evaluated: positive psychotic symptoms, depressive symptoms, medication side effects, social functioning, occupational functioning, and general life satisfaction. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist–90 items in the PORT mental health survey were used to construct a measure of positive psychotic symptoms. The six items used to define this construct were 1) the idea that someone else can control your thoughts, 2) hearing voices that others do not hear, 3) believing that other people are aware of your private thoughts, 4) having thoughts that are not your own, 5) feeling that most people cannot be trusted, and 6) feeling that you are watched or talked about by others. The first four items were taken from the Hopkins Symptom Checklist–90 psychoticism factor, and the other two items were taken from the paranoid ideation factor. The complete psychoticism factor was not used because it contains items that are not related to positive psychotic symptoms (e.g., feeling lonely even when you are with people, thinking that you should be punished for your sins, never feeling close to another person) (12). The Hopkins Symptom Checklist–90 depression factor items were used to assess depressive symptoms. The PORT mental health survey items derived from the Quality of Life Interview were used to assess social and occupational functioning and general life satisfaction. Six items assessed the frequency and quality of social contacts with family members and friends. The following four categories of occupational functioning were evaluated: paid employment or full-time student status, volunteer or homemaker, structured day program or part-time student status, and unemployed. In the analyses, the first three levels of employment were combined, and occupational functioning was classified as a categorical yes (employed)/no (not employed) variable. General life satisfaction was assessed with a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 0, terrible, to 7, delighted. The following eight self-report items from the PORT mental health survey were used to assess the presence of medication side effects: sedation, restlessness, feeling slowed down, tremor, blurred vision/dry mouth, difficulty concentrating/forgetfulness, impaired sexual function, and weight gain. Three of these items (i.e., restlessness, feeling slowed down, and tremor) were used to assess conformance with the PORT recommendation for adjunctive treatment with antiparkinsonian agents.

Statistical Analyses

Three conformance categories were used: conformant, nonconformant, and indeterminate. Indeterminate conformance with a specific treatment recommendation occurred when a subject received the adjunctive treatment but did not report the symptom or diagnostic indicator for the adjunctive treatment; e.g., a patient was treated with an antidepressant but did not report either depressive symptoms or a current diagnosis of depression. Subjects whose treatment had indeterminate conformance may represent patients who were appropriately and effectively treated or patients who were overtreated. Conformance rates were calculated by using data from only those subjects whose treatment was either conformant or nonconformant. Chi-square statistics were used to assess conformance rate differences with respect to the class of antipsychotic medication received (e.g., conventional antipsychotics only versus new-generation antipsychotics only).

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) (for continuous variables) or chi-square analysis (for categorical variables) were conducted to examine the bivariate relationships between conformance with treatment recommendations (conformant/nonconformant/indeterminate) and demographic and clinical variables. If the relationship between a demographic or clinical variable and conformance status was significant, the appropriate post hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted to determine group differences.

Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to examine the relationship of conformance with treatment recommendation to symptom and function measures. Class of antipsychotic and any demographic or clinical variable associated with a p value less than 0.05 in the bivariate analyses were included as covariates. The covariates for each model are specified in the presentation of the results. If the overall model statistic was significant, then the type III sum-of-squares statistic was used to examine whether treatment recommendation conformance contributed significantly to the model. If the relationship between a symptom or level-of-function measure and conformance was significant, the appropriate post hoc pairwise comparisons were performed by using the procedure of Edwards and Berry (13) to keep the overall type I error rate at alpha=0.05. Adjusted p values were obtained by estimating the probability of obtaining pairwise t statistics at least as extreme as those observed under the null hypothesis by simulation from a multivariate t distribution with correlation parameters estimated from the correlation structure of the observed data. For unbalanced data, these simulation estimates can be more accurate than approximated methods such as the Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test. Only the adjusted p values are cited in the text, as the pairwise t statistics would give a misleading impression of the correct p value for the test.

Before conducting any ANCOVAs, we examined each potential covariate to determine whether assumptions of homogeneity of regression were met. For several categorical variables, the assumption was not met, and analyses were conducted separately for each categorical variable group. In the analyses of the relationships between conformance with treatment recommendations for adjunctive antiparkinsonian agents and medication side effects, adjunctive antidepressant treatment recommendation conformance and the Hopkins Symptom Checklist–90 depression factor, and adjunctive mood stabilizer treatment recommendation conformance and the Hopkins Symptom Checklist–90 positive psychotic symptoms measure, a symptom measure was used to define whether the subject’s treatment was conformant, nonconformant, or indeterminate. Therefore, conformant-indeterminate or nonconformant-indeterminate group differences would be tautological and are interpreted accordingly.

The alpha level for the analyses examining the relationships of treatment recommendation conformance with demographic and clinical variables and with symptom and level-of-function measures was set at 0.01 to account for the multiple comparisons and to reduce the rate of type I error.

Results

A total of 379 subjects underwent the PORT mental health survey and outpatient record review assessments. Thirty-five subjects were excluded because 1) an antipsychotic had not been prescribed for them (N=14), 2) some data from the survey interview or record review were missing for them (N=20), and 3) they were a clinical trial research subject (N=1). A total of 344 subjects were included in the final study group. In a comparison of the demographic characteristics of the patients who were included (N=344) and those who were excluded (N=673), there were no significant differences in gender (χ2=0.98, df=1, p=0.32) or age distribution (χ2=0.72, df=2, p=0.70). However, the two groups differed significantly in ethnicity. Of the patients who were included, 59.6% were white and 40.4% were nonwhite, compared with 67.2% and 32.8%, respectively, of the patients who were excluded (χ2=5.24, df=1, p=0.02). The demographic and clinical characteristics of the final study group are presented in Table 1.

Of the patients included in the study, 259 (75.3%) were receiving at least one adjunctive agent. Eighty-eight patients (25.6%) were treated with only adjunctive antiparkinsonian agents, 101 (29.4%) with an antiparkinsonian agent and at least one other adjunctive agent, and 70 (20.3%) with at least one adjunctive agent other than an antiparkinsonian agent. Fifty-four patients (15.7%) were receiving two or more nonantiparkinsonian adjunctive agents.

Conformance Rates

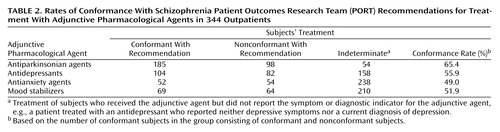

The numbers of subjects whose treatment was conformant, nonconformant, and indeterminate for each treatment recommendation are presented in Table 2. The conformance rates ranged from a low of 49.0% for the use of adjunctive antidepressants to a high of 65.4% for the use of adjunctive antiparkinsonian agents.

Class of antipsychotic medication was significantly related to conformance with the treatment recommendation for adjunctive antiparkinsonian agents (χ2=24.6, df=2, p=0.001). In the post hoc pairwise comparisons, the treatment of patients who received conventional antipsychotics was significantly more likely to be conformant (χ2=19.0, df=1, p<0.0001) and significantly less likely to be indeterminate (χ2=17.2, df=1, p<0.001) than the treatment of those who received new-generation antipsychotics. The difference between the conventional and new-generation groups was primarily driven by the large number of clozapine-treated patients who reported extrapyramidal side effects but were not treated with an antiparkinsonian agent. There were no significant effects of class of antipsychotic on conformance with the other treatment recommendations.

Demographic and Clinical Variables

Results for the relationship between conformance with treatment recommendations for adjunctive agents and patients’ demographic and clinical variables are presented separately for each type of adjunctive agent.

Antiparkinsonian agents

There were no significant relationships between any of the demographic and clinical variables and conformance with the treatment recommendation for adjunctive antiparkinsonian agents.

Antidepressants

Locale (χ2=8.48, df=2, p=0.01) and diagnosis (χ2=20.4, df=2, p=0.001) were significantly related to conformance with the treatment recommendation for adjunctive antidepressant agents. In the post hoc pairwise comparisons for locale, the treatment of patients in rural settings was significantly more likely to be conformant than the treatment of those in urban settings (χ2=7.31, df=1, p=0.007). In the post hoc comparisons for diagnosis, the treatment of patients with schizophrenia was significantly less likely to be conformant (χ2=6.80, df=1, p=0.009) and significantly more likely to be indeterminate (χ2=1.94, df=1, p<0.0001) than the treatment of patients with schizoaffective disorder.

Antianxiety agents

Ethnicity (χ2=24.6, df=2, p=0.001) and diagnosis (χ2=23.6, df=2, p=0.001) were significantly related to conformance with the treatment recommendation for adjunctive antianxiety agents. In the post hoc pairwise comparisons for ethnicity, the treatment of white subjects was significantly more likely than that of nonwhite subjects to be classified as either conformant (χ2=13.6, df=1, p=0.0002) or nonconformant (χ2=14.8, df=1, p=0.0001); i.e., the treatment of nonwhite subjects was more likely to be classified as indeterminate. In the post hoc pairwise comparisons for diagnosis, patients with schizophrenia were more likely than patients with schizoaffective disorder to have treatment that was classified as indeterminate (χ2=22.4, df=1, p<0.0001).

Mood stabilizers

Ethnicity (χ2=9.24, df=2, p=0.01), diagnosis (χ2=31.6, df=2, p=0.001), and substance abuse (χ2=9.01, df=2, p=0.01) were significantly related to conformance with the treatment recommendation for adjunctive mood stabilizers. In the post hoc pairwise comparison for ethnicity, white subjects were significantly more likely than nonwhite subjects to have treatment that was conformant (χ2=9.0, df=1, p=0.03). In the post hoc pairwise comparison for diagnosis, patients with schizophrenia were significantly less likely to have conformant treatment than patients with schizoaffective disorder (χ2=18.8, df=1, p<0.0001). In the post hoc pairwise comparison for substance abuse, patients whose treatment conformed to the recommendation were significantly less likely than patients with nonconformant treatment to exhibit current substance abuse (χ2=7.5, df=1, p=0.006).

Symptoms and Level of Function

The relationships between treatment recommendation conformance and symptom and level-of-function measures for which the overall ANCOVA was significant are presented in Table 3. The demographic and clinical variables that met entry criteria (p<0.05 in the bivariate analyses; see Statistical Analyses section) and were included in the analytical models as covariates are specified at the beginning of each subsection.

Antiparkinsonian agents

Ethnicity (χ2=7.15, df=2, p=0.03) and psychiatric hospitalization during the past year (χ2=6.60, df=2, p=0.04) met entry criteria and were included as covariates in the statistical model. The overall model statistic was significant for medication side effects. Treatment recommendation conformance contributed significantly to the model (F=38.22, df=2, 315, p=0.0001).

In the post hoc pairwise comparisons, patients whose treatment was conformant with the recommendation for adjunctive antiparkinsonian agents were less likely to experience medication side effects than patients with nonconformant treatment (p=0.007). There were also significant differences in medication side effects between the conformant and indeterminate groups (p=0.0001) and the nonconformant and indeterminate groups (p=0.0001). These latter differences are consistent with the use of patients’ reports of extrapyramidal side effects to define conformance with the treatment recommendation for adjunctive antiparkinsonian agents.

Antidepressants

Locale (χ2=8.48, df=2, p=0.01), diagnosis (χ2=20.4, df=2, p=0.001), and psychiatric hospitalization during the past year (χ2=6.35, df=2, p=0.04) met entry criteria and were included as covariates in the statistical model. The overall model was significant for the Hopkins Symptom Checklist–90 positive psychotic symptoms measure, the Hopkins Symptom Checklist–90 depression factor, medication side effects, and general life satisfaction. Treatment recommendation conformance contributed significantly to each of these models (positive psychotic symptoms measure: F=15.73, df=2, 320, p=0.0001; depression factor: F=50.82, df=2, 321, p=0.0001; medication side effects: F=10.73, df=2, 315, p=0.0001; and general life satisfaction: F=14.17, df=2, 321, p=0.0001).

In the post hoc pairwise comparisons for the positive psychotic symptoms measure, the depression factor, medication side effects, and general life satisfaction, there were significant differences between patients whose treatment was conformant and those whose treatment was indeterminate and between those with nonconformant treatment and those with indeterminate treatment. Compared with the indeterminate group, the conformant and nonconformant groups had more positive symptoms (p=0.002 and p=0.0001, respectively), higher depression factor scores (p=0.0001 and p=0.0001), more medication side effects (p=0.0002 and p=0.0006), and less general life satisfaction (p=0.0001 and p=0.0002). The differences between the conformant and indeterminate groups and the nonconformant and indeterminate groups on the depression factor are consistent with the use of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist–90 depression factor to define, in part, conformance with the recommendation for adjunctive antidepressants treatment. There were no significant conformant and nonconformant group differences on the depression factor.

Antianxiety agents

Ethnicity (χ2=24.6, df=2, p=0.001) and diagnosis (χ2=23.6, df=2, p=0.001) met entry criteria and were included as covariates in the statistical model. The overall model statistics were significant for the Hopkins Symptom Checklist–90 positive psychotic symptoms measure and depression factor (both variables were analyzed separately for white and nonwhite subjects). Treatment recommendation conformance contributed significantly to the models that included nonwhite subjects (positive psychotic symptoms measure: F=10.59, df=2, 133, p=0.0001; depression factor: F=16.24, df=2, 134, p=0.0001).

In the post hoc pairwise comparisons for the positive psychotic symptoms measure and the depression factor, there were significant differences for nonwhite subjects only between the conformant and indeterminate groups and between the nonconformant and indeterminate groups. Compared with the indeterminate group, the conformant and nonconformant groups had more positive symptoms (p=0.0005 and p=0.002, respectively) and higher depression factor scores (p=0.0001 and p=0.0002). There were no significant differences between the conformant and nonconformant groups.

Mood stabilizers

Ethnicity (χ2=9.24, df=2, p=0.01), diagnosis (χ2=20.4, df=2, p=0.001), and substance abuse (χ2=9.01, df=2, p=0.01) met entry criteria and were included as covariates in the statistical model. The overall model statistics were significant for the Hopkins Symptom Checklist–90 positive psychotic symptoms measure, the Hopkins Symptom Checklist–90 depression factor, medication side effects, and general life satisfaction. Treatment recommendation conformance contributed significantly to each of these models (positive psychotic symptoms: F=194.91, df=2, 320, p=0.0001; depression factor: F=43.74, df=2, 320, p=0.0001; medication side effects: F=13.98, df=2, 314, p=0.0001; and general life satisfaction: F=11.63, df=2, 320, p=0.0001).

In the post hoc pairwise comparisons for the positive psychotic symptoms measure, the patients with conformant treatment had significantly fewer positive psychotic symptoms than the patients with nonconformant treatment (p=0.0001). There were also significant differences between the conformant group and the indeterminate group (p=0.03) and between the nonconformant group and the indeterminate group (p=0.0001). These latter group differences are consistent with the use of the positive psychotic symptoms measure to define conformance with the treatment recommendation for adjunctive mood stabilizers.

In the post hoc pairwise comparisons for the depression factor, the conformant and indeterminate groups had significantly lower depression factor scores than the nonconformant group (p=0.0001 for both comparisons). In the post hoc pairwise comparisons for medication side effects, the conformant and nonconformant groups were significantly more likely to experience medication side effects than the indeterminate group (p=0.02 and p=0.0001, respectively). In the post hoc pairwise comparisons for general life satisfaction, the conformant and indeterminate groups had significantly higher general life satisfaction scores than the nonconformant group (p=0.01 and p=0.0001, respectively).

Discussion

The study results indicate that adjunctive agents are extensively used in the pharmacological treatment of patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Seventy-five percent of all patients in the study were receiving at least one adjunctive agent, and 30% were receiving two or more adjunctive agents. The use of adjunctive agents extended well beyond antiparkinsonian agents. Fifty percent of all patients were treated with an adjunctive agent other than an antiparkinsonian agent.

The highest conformance rate was for the PORT treatment recommendation for adjunctive antiparkinsonian agents, with almost two-thirds of the outpatient subjects having conformant treatment. This high conformance rate suggests that these agents are appropriately used for the majority of patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. There was a significant difference in conformance with the treatment recommendation for adjunctive antiparkinsonian agents between patients treated with conventional antipsychotics and those treated with new-generation antipsychotics. This difference was primarily driven by the large number of clozapine-treated patients who reported extrapyramidal side effects but were not treated with an antiparkinsonian agent. In light of the very low incidence of extrapyramidal side effects associated with clozapine treatment (14), this was an unexpected finding. The most likely explanation is that the use of self-report items rather than an objective measure of extrapyramidal side effects led to an overestimation of the presence of extrapyramidal side effects through the misattribution of other symptoms. Sedation was the most common medication side effect in the clozapine-treated patients with nonconformant treatment, and sedation may have been self-reported as the extrapyramidal symptom of “feeling slowed down,” which was the most commonly reported extrapyramidal symptom. The failure to use antiparkinsonian agents for these patients supports the plausibility of this interpretation.

The conformance rate data for adjunctive antidepressants, antianxiety agents, and mood stabilizers do not provide as clear support for the extensive use of these agents. This is partly because it was not possible to ascertain the presence of the indicator for the need for the adjunctive agent in a large number of patients, who were subsequently classified as having indeterminate treatment. The subjects whose treatment was classified as indeterminate represent an ambiguous group. They may have previously presented with a treatment indicator and may have been effectively treated, or they may be receiving an adjunctive treatment without any indication for the treatment. Their inclusion in the conformant group would lead to a potential overestimation of the appropriate use of adjunctive agents, whereas their exclusion from this group, as was done in the current study, may lead to an underestimation of conformance rates. These possibilities result from the limitations of cross-sectional data assessment. Longitudinal, prospective studies would enable a more precise determination of the presence of treatment indicators, reduce the number of indeterminate cases, and provide a more accurate evaluation of the appropriate use of these agents.

Ethnicity and diagnosis were the only demographic and clinical variables that were significantly related to conformance for more than one treatment recommendation. White subjects were more likely than nonwhite subjects to have appropriately received a prescription for mood stabilizers to treat persistent and clinically significant positive symptoms. Although the difference was not significant, white subjects also had higher conformance rates for adjunctive antidepressants. However, a significantly higher proportion of nonwhite than of white subjects were treated with adjunctive antianxiety agents; i.e., a higher proportion of nonwhite subjects had treatment that was either conformant or indeterminate. These results suggest that prescription practices may vary with ethnicity and that ethnicity may have a specific effect on the prescription of antidepressants and mood stabilizers. Previous research has observed that nonwhite subjects are more likely to be given a diagnosis of schizophrenia and less likely to be given a diagnosis of affective disorders (15). This effect of ethnicity may extend to the agents used to treat these conditions.

Outpatients with schizophrenia were significantly less likely than those with schizoaffective disorder to have treatment that was conformant with either the adjunctive antidepressant or the adjunctive mood stabilizer treatment recommendations. The lower frequency of use of adjunctive antidepressants in outpatients with schizophrenia suggests that the identification of affective symptoms through a formal diagnosis increases the likelihood that patients with depressive symptoms will actually receive appropriate antidepressant therapy. The actual effectiveness of this therapy is unclear (see later discussion). The significance of the diagnostic effect for mood stabilizers is less clear, as many patients with schizoaffective disorder may be receiving mood stabilizers for manic-like symptoms as well as persistent positive symptoms.

Conformance with treatment recommendations for adjunctive agents had a mixed relationship with measures of symptoms and level of function. Conformance was unrelated to social or occupational function measures. There are at least two possible explanations for the lack of association. First, extrapyramidal side effects, anxiety, depressive symptoms, and persistent positive symptoms may not have important relationships to these functional measures, so that conformance with the treatment recommendations for these symptoms does not affect these measures. This interpretation is consistent with previous studies (16, 17). Alternatively, the large number of indeterminate cases may have precluded the detection of a significant benefit of these adjunctive agents for these measures.

The observed relationships of treatment recommendation conformance for adjunctive antiparkinsonian, antidepressant, and antianxiety agents with positive psychotic and depressive symptom measures, medication side effects, and general life satisfaction were almost entirely related to the differences between the conformant and indeterminate groups and between the nonconformant and indeterminate groups. The only significant difference between the conformant and nonconformant groups was in the relationship between medication side effects and conformance with the treatment recommendation for adjunctive antiparkinsonian agents, for which patients with conformant treatment were less likely than those with nonconformant treatment to report medication side effects. There was no evidence that conformance with recommendations for antidepressants or antianxiety agents was clinically important. These results differ from the results of the efficacy studies on which these recommendations were based (1). The failure to detect a significant benefit for conformant antidepressant treatment suggests several possible explanations. There may be community factors, not identified in the current study, that decrease the effectiveness of this intervention. Alternatively, the large number of subjects in the indeterminate group (N=158) may have led to an underestimation of the potential benefit of adjunctive antidepressants. Although there was no benefit of adjunctive antianxiety agents for positive or depressive symptoms, the lack of a specific anxiety symptom measure precluded a more detailed evaluation of the effectiveness of these agents.

The use of mood stabilizers in conformance with the PORT treatment recommendation was the only adjunctive treatment that had a consistent beneficial effect. Compared with nonconformance, conformance with the treatment recommendation for adjunctive mood stabilizers was associated with significantly less persistent positive and depressive symptoms and significantly higher general life satisfaction. The apparent benefit of mood stabilizers for positive symptoms provides strong support for the extensive clinical use of these agents, but it is contrary to the results of previous clinical trials that have failed to find a benefit of mood stabilizers for these symptoms (1). Although the discrepancy may represent a rare occurrence of a pharmacological intervention having greater effectiveness than efficacy, the most likely explanation is the cross-sectional design of the current study. A longitudinal study would be required to confirm the actual effectiveness of these agents.

In addition to the self-report extrapyramidal side effects measure and the cross-sectional study design, the other major study limitation was the marked attrition. The final study group represented approximately one-third of the original screened population. The marked attrition rate raises concerns about the applicability of the current findings to the general outpatient population. There were no significant differences in gender or age distribution between the patients who were included or excluded from the study, but there was a significant difference in ethnicity, with a greater percentage of nonwhite subjects among those included in the study. This demographic difference would have been of greater concern if nonwhite subjects had been underrepresented in the study group. However, the included and excluded groups may differ on other clinical variables for which data were not available for comparison and which would compromise the generalizability of the current findings.

In summary, adjunctive agents are widely used in the pharmacological treatment of patients with schizophrenia. The extent to which these agents are appropriately used and the ultimate benefit of these agents are unclear. Longitudinal, prospective studies will be required to demonstrate the clinical utility of these practices.

Acknowledgments

The principal investigator and co-principal investigator for the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) are, respectively, Anthony F. Lehman, M.D., M.S.P.H., of the Center for Mental Health Services Research, University of Maryland, and Donald M. Steinwachs, Ph.D., of the Health Services Research and Development Center, Johns Hopkins University School of Hygiene and Public Health. PORT co-investigators include Robert W. Buchanan, M.D., William T. Carpenter, Jr., M.D., and Jerome Levine, M.D., of the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center; Lisa B. Dixon, M.D., M.P.H., Howard H. Goldman, M.D., Ph.D., Fred Osher, M.D., Leticia Postrado, Ph.D., Jack E. Scott, Sc.D., and James Thompson, M.D., M.P.H., of the Center for Mental Health Services Research, University of Maryland; Susan dosReis, B.S. Pharm., and Julie Kreyenbuhl, Pharm.D., of the Department of Pharmacy Practice and Science, University of Maryland School of Pharmacy; Maureen Fahey, M.L.A., Judith D. Kasper, Ph.D., Alan Lyles, Sc.D., M.P.H., Andrew D. Shore, Ph.D., and Elizabeth A. Skinner, M.S.W., of the Johns Hopkins University School of Hygiene and Public Health; Pamela J. Fischer, Ph.D., of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine; Elizabeth McGlynn, Ph.D., of the RAND Corporation; Robert Rosenheck, M.D.; of the Veterans Affairs Northeast Program Evaluation Center and Yale University; and Julie Magno Zito, Ph.D., of the Center for Mental Health Services Research, University of Maryland, and the Department of Pharmacy Practice and Science, University of Maryland School of Pharmacy.

|

|

|

Received Dec. 14, 2000; revision received June 13, 2001, accepted Nov. 7, 2001. From the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center, Department of Psychiatry, University of Maryland; the Center for Mental Health Services Research, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore; and the Department of Pharmacy Practice and Science, University of Maryland School of Pharmacy, Baltimore. Address reprint requests to Dr. Buchanan, Maryland Psychiatric Research Center, P.O. Box 21247, Baltimore, MD 21228; [email protected] (e-mail). The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) was funded by the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR) and the National Institute of Mental Health (AHCPR contract number 282-92-0054).

|

Appendix 1.

1. Johns CA, Thompson JW: Adjunctive treatments in schizophrenia: pharmacotherapies and electroconvulsive therapy. Schizophr Bull 1995; 21:607-619Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM (co-investigators of the PORT project): At issue: translating research into practice: the schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophr Bull 1998; 24:1-10Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM (co-investigators of the PORT project): Patterns of usual care for schizophrenia: initial results from the schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) client survey. Schizophr Bull 1998; 24:11-20Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Lehman AF: The well-being of chronic mental patients: assessing their quality of life. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983; 40:369-373Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Midanik LT, Zahnd EG, Klein D: Alcohol and drug CAGE screeners for pregnant, low-income women: the California Perinatal Needs Assessment. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1998; 22:121-125Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Covi L: SCL-90: an outpatient psychiatric rating scale—preliminary report. Psychopharmacol Bull 1973; 9:13-28Medline, Google Scholar

7. Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, Meltzer H (Clozaril Collaborative Study Group): Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic: a double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:789-796Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Marder SR, Meibach RC: Risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:825-835Link, Google Scholar

9. Zito JM: Psychotherapeutic Drug Manual, 3rd ed. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1994Google Scholar

10. Peuskens J (Risperidone Study Group): Risperidone in the treatment of patients with chronic schizophrenia: a multi-national, multi-centre, double-blind, parallel-group study versus haloperidol. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 166:712-726Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Buchanan RW, Breier A, Kirkpatrick B, Ball P, Carpenter WT Jr: Positive and negative symptom response to clozapine in schizophrenic patients with and without the deficit syndrome. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:751-760Link, Google Scholar

12. Derogatis LR, Cleary PA: Confirmation of the dimensional structure of the SCL-90: a study in construct validation. J Clin Psychol 1977; 3:981-989Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Edwards D, Berry JJ: The efficiency of simulation-based multiple comparisons. Biometrics 1987; 43:913-928Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Buchanan RW: Clozapine: efficacy and safety. Schizophr Bull 1995; 21:579-591Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Baker FM, Bell CC: Issues in the psychiatric treatment of African Americans. Psychiatr Serv 1999; 50:362-368Link, Google Scholar

16. Green MF: What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:321-330Link, Google Scholar

17. Green MF, Nuechterlein KH: Should schizophrenia be treated as a neurocognitive disorder? Schizophr Bull 1999; 25:309-318Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar