Special Section on CATIE Baseline Data: Baseline Use of Concomitant Psychotropic Medications to Treat Schizophrenia in the CATIE Trial

The introduction of first-generation antipsychotic drugs in the 1950s for the treatment of schizophrenia was an enormous advance over the treatments at that time. Unfortunately for most patients, response was at best partial. As such, clinicians struggled to find strategies to improve outcome by augmenting the treatment with so-called ancillary or concomitant psychotropic medications. These strategies included combining antipsychotics or combining an antipsychotic with an antidepressant, a mood stabilizer, anxiolytic agents, or sedatives. This strategy has not changed even with the introduction of second-generation agents. In fact, polypharmacy has become the rule rather than the exception in the United States and elsewhere ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ). This change has evolved despite an almost total lack of controlled scientific data supporting the practice ( 10 , 11 ). The evidence has been mostly anecdotal.

In addition, there are several risks working against the benefits of this practice. Concomitant use of psychotropic medications may worsen the patient's quality of life, induce side effects, and create drug interactions that decrease medication efficacy. In addition, and important for many settings and patients, treatment costs can increase dramatically. Moreover, the more complex the medication regimen is, the lower the treatment compliance.

In this study we describe the frequency and the demographic and clinical correlates of concomitant use of psychotropic medications among participants in the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) before they were randomly assigned to a treatment group. This study differentiates itself from prior studies on use of polypharmacy to treat schizophrenia in that patients in the CATIE study had much greater exposure to second-generation antipsychotics, whereas previous studies were conducted with patients who were primarily treated with first-generation antipsychotics. Thus this study is a more up-to-date evaluation of the impact of second-generation antipsychotics on the practice of polypharmacy.

Methods

The CATIE study was designed to compare the effectiveness of currently available second-generation antipsychotics with a representative first-generation antipsychotic, perphenazine, through a randomized clinical trial that involved a large sample of patients treated for schizophrenia at multiple sites, including both academic and community providers. Patients who met criteria for schizoaffective disorder, depressive type (with predominant schizophrenic features), could also participate if approved by the project's medical officer. Participants provided written informed consent to participate in protocols approved by local institutional review boards. Of the 1,460 patients, 77 percent were male, 60 percent were white, 35 percent were African American, and 5 percent were of other racial backgrounds. The mean±SD age was 40±11. Approximately 25 percent of patients had an exacerbation of illness in the three months before study entry. Patients had been taking antipsychotic medications for approximately 14 years. The average Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) score at baseline was 75, and the average Clinical Global Index was 4. Details of the study design of the CATIE study and entry criteria have been presented elsewhere ( 12 , 13 ). This study presents baseline data collected from 2001 to 2003 from participants with schizophrenia before random assignment and initiation of study treatments.

Measures

As part of the baseline assessment, patients were asked to report all medications they were currently prescribed. Study personnel also reviewed patients' medical records and spoke to treating clinicians (when available) to determine medications that were prescribed. The dependent variables in this study were a series of dichotomous measures representing various classes of prescribed medications. The first measure was a general category indicating use of at least one of the following seven classes of psychotropic medication: first-generation antipsychotics, second-generation antipsychotics, antidepressants, anxiolytic agents, sedative-hypnotics, mood stabilizers (valproic acid or carbamazepine), and lithium. The group taking at least one psychotropic medication was then divided into participants taking no antipsychotic as contrasted with those taking one or more antipsychotics. The third and fourth measures represented use of a first- or second-generation antipsychotic among those taking any antipsychotics, and a fifth measure represented taking both a first- and a second-generation medication. No patients were taking two second-generation antipsychotics.

Five additional measures represented each of the other classes of psychotropic medication among patients taking medication. One additional dichotomous measure represented use of an anticholinergic medication among patients on any antipsychotic. A final, continuous measure represented the total number of different agents taken by each patient (excluding anticholinergics) among those taking any such medication.

The diagnosis of schizophrenia was confirmed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID) ( 13 ) for all patients, and SCID data were also available on secondary axis I diagnoses. Symptoms of schizophrenia were assessed with the rater-administered PANSS ( 14 ). Overall quality of life and functioning were assessed with the Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale (QOLS) ( 15 ) and the global quality-of-life item measured with the Lehman Quality of Life Interview ( 16 ).

Medication side effects were assessed with the Barnes scale for akathisia ( 17 ), the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) for tardive dyskinesia ( 18 ), and the Simpson-Angus scale for extrapyramidal side effects (SAEPS) ( 19 ). Depression was measured with the Calgary Depression Rating Scale ( 20 ). For this article substance use was defined by SCID diagnosis.

Neurocognitive functioning was measured by separate test scores, described in a previous publication ( 21 ), which were converted to z scores and combined to construct five separate scales (processing speed, verbal memory, vigilance, reasoning, and working memory) that were themselves averaged to form an overall neurocognitive functioning scale. Higher overall neurocognitive scores indicated better functioning. Neurocognitive data were missing for 8 percent of the sample (N=117), and the missing data were imputed by substituting the mean value for the whole group.

Statistical analysis

First, a large group of potential predictors were screened with bivariate Spearman correlation analysis to identify sociodemographic and clinical correlates of each measure of medication use. Measures that were significant in bivariate analyses at p<.01 were then included in a subsequent series of stepwise multivariate logistic regression analyses that identified independent correlates of each measure of medication use. Stepwise linear regression models were used to identify correlates of the total number of medication classes and agents. Values with a p value of less than .01 are shown in the tables.

Results

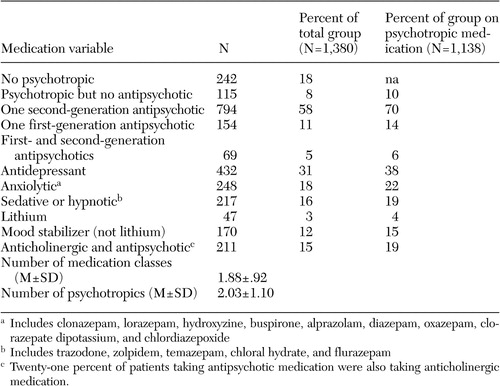

In the CATIE study, 1,493 participants were randomly assigned to the schizophrenia component of the study. Data from one site (33 patients) were excluded from all analyses because of concerns about their integrity, leaving 1,460 patients at the baseline cut. Medication data were available for 95 percent (N=1,380) of these patients. Eighty-two percent (N=1,138) of patients were taking a psychotropic medication from one of the seven classes. Table 1 summarizes the frequencies of psychotropic use by category.

|

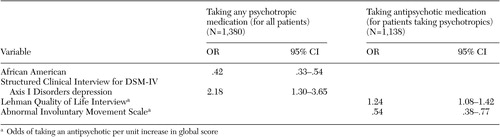

No psychotropic or no antipsychotic medication

Twenty-six percent of patients (N=357) entering the trial were not taking any antipsychotic medication. Eighteen percent of the patients (N=242) were taking no psychotropic medication at study entry, and 8 percent (N=115) were taking a psychotropic medication but no antipsychotic medication. Participants who were not taking psychotropic medication were more likely to be African American and were less likely to have SCID diagnoses of depression ( Table 2 ). Participants who were taking psychotropic but not antipsychotic medications had higher AIMS scores and lower scores on the Lehman Quality of Life Interview ( Table 2 ).

|

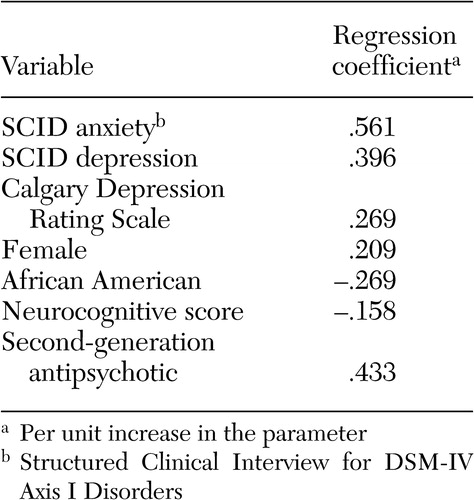

Numbers and classes of concomitant medications

The mean±SD number of psychotropic medications per patient for those who were taking at least one psychotropic at baseline was 2.03±1.1. The strongest predictors of taking multiple psychotropic medications were being anxious or depressed, being female, and being treated with a second-generation antipsychotic. Conversely, African-American patients and those with better neurocognitive functioning were less likely to be taking several psychotropic medications ( Table 3 ).

|

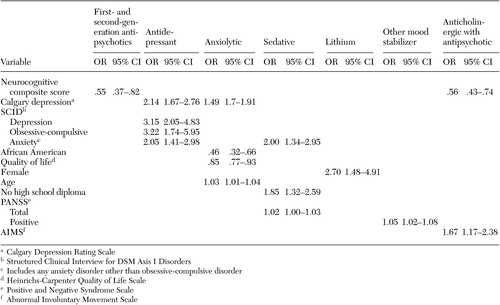

Antipsychotic polypharmacy

At baseline, 69 participants (5 percent) were taking two antipsychotic agents, one that was first generation and the other, second generation. No patients were taking more than two antipsychotics. The neurocognitive composite score showed a negative association with the use of antipsychotic polypharmacy (odds ratio [OR]=.55; 95 percent confidence interval [CI]=.37-.82) ( Table 4 ), indicating that patients with lower neurocognitive scores were more likely to be taking two agents.

|

Anticholinergics

Of the 1,017 patients taking antipsychotic medications, 211 patients (21 percent) were receiving adjunctive anticholinergic treatment. Anticholinergic medications were being taken by 93 of the 794 patients (12 percent) who were taking a second-generation antipsychotic, 81 of the 154 patients (53 percent) who were taking a first-generation antipsychotic, and 37 of the 67 patients (55 percent) who were taking a combination of first- and second-generation antipsychotic medications. After including age, gender, race, Barnes akathisia scale ratings, SAEPS, and PANSS negative and positive symptom scores in the model, the use of anticholinergic medications by those receiving an antipsychotic medication was associated with poorer neurocognitive functioning (OR=.55, CI= .37-.82) ( Table 4 ).

Mood stabilizers and antidepressants

Four percent (N=47) of patients who were taking psychotropic medications received treatment with lithium, and 15 percent (N=170) were receiving other mood stabilizers (valproic acid or carbamazepine). Female gender predicted adjunctive treatment with lithium. Higher PANSS positive symptom scores predicted adjunctive treatment with other mood stabilizers ( Table 4 ).

Thirty-eight percent of patients who were taking psychotropic medications (N=432) were receiving antidepressant treatment. Additional SCID diagnoses of major depressive disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and any other anxiety disorder independently predicted adjunctive treatment with antidepressants. Even after SCID diagnoses for generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder were included in the model, higher scores on the Calgary Depression Rating Scale predicted adjunctive antidepressant use. Gender, race, akathisia scale, SAEPS, and PANSS negative and positive symptom scores were not predictors of antidepressant use.

Anxiolytics and sedatives

Twenty-two percent (N=248) of patients taking psychotropic medications received anxiolytics. Even after SCID diagnoses for generalized anxiety, major depressive, and obsessive-compulsive disorders were included in the model, higher Calgary depression scores predicted adjunctive anxiolytic use. African-American patients were less likely to receive anxiolytic medications, and use of anxiolytic medication was associated with worse functioning on the Heinrichs-Carpenter QOL scale ( Table 4 ).

Nineteen percent (N=217) of patients who were taking psychotropic medications received sedative-hypnotics. Older patients and patients with less than a high school education were more likely to receive sedative hypnotics. Patients with a comorbid diagnosis of anxiety disorder and those with higher positive symptom scores were more likely to receive sedative hypnotics ( Table 4 ).

Discussion

Prevalence of use of psychotropic medications

Antipsychotic polypharmacy has increased over the years and is prescribed to 25 percent of outpatients and more than 50 percent of inpatients with schizophrenia in the United States and to 13 to 90 percent of patients internationally ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 11 , 22 , 23 ). Whereas prior examinations of antipsychotic polypharmacy were conducted for patients with schizophrenia who had much greater exposure to first-generation antipsychotic medications, the study reported here was conducted for patients who had a much greater exposure to second-generation antipsychotic medications. The 5 percent prevalence rate of antipsychotic polypharmacy in our study is relatively low compared with the rates in other studies. This may reflect the greater use of second-generation antipsychotics in the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. However, patients treated with multiple antipsychotic medications also may have been less likely to be referred to the study.

Our findings on the prevalence of use of psychotropic medications, including 31 percent taking antidepressants, 18 percent taking anxiolytics, 16 percent taking sedative-hypnotics, and 15 percent taking anticholinergic medication in combination with an antipsychotic, are similar to the prevalence rates of use of psychotropic medications among patients with schizophrenia reported by other investigators ( 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 ). In contrast, the prevalence of use of mood stabilizers (3 percent taking lithium, 12 percent taking other mood stabilizers) was relatively low compared with these prior studies. Because patients who entered this study had much greater exposure to second-generation medications than in prior studies of antipsychotic polypharmacy, the finding suggests that clinicians are less likely to prescribe mood stabilizers with second-generation antipsychotics.

Correlates of concomitant use of psychotropic medications

A broad array of factors was associated with concomitant psychotropic treatment of patients with schizophrenia in this trial. With respect to demographic predictors of concomitant use of psychotropic medications, African-American participants received fewer concomitant psychotropic medications and anxiolytics, whereas women received more concomitant psychotropic medications, especially antidepressants and lithium. Female patients may have been taking more concomitant psychotropic medications because women generally are better able to express their symptoms of anxiety and depression to their providers, which in this case may have resulted in an increase in prescriptions of concomitant psychotropic medications. Alternatively, the female patients perhaps were more likely to experience these symptoms. A prescriber bias is another possible explanation for this difference. Less frequent use of anxiolytics among African-American patients is consistent with findings of other investigators ( 9 , 34 ) and may reflect prescriber bias, economic factors, or less engagement in the mental health system ( 34 , 35 ).

Both the number of concomitant psychotropic medications and the use of antidepressants and anxiolytics had no association with positive or negative symptoms of schizophrenia but were associated with symptoms of anxiety and depression. The lack of an association of antidepressant or anxiolytic use with positive symptoms or potential confounders of depression, such as negative symptoms and extrapyramidal side effects, suggests that symptoms of depression and anxiety are components of the illness that are independent of positive or negative symptoms or side effects such as extrapyramidal effects. The increase in prescribing concomitant psychotropic medications to patients with symptoms of anxiety and depression suggests that physicians have become very responsive to treating these symptoms among patients with schizophrenia. This may in part be due to patients' complaints about these ancillary symptoms and patients' increased expectations of treatments to relieve them but may also reflect the physician's desire to ameliorate the feeling of demoralization and anxiety associated with having to deal with this chronic illness.

The association of more severe depressive symptoms with concomitant antidepressant use, in the form of higher Calgary depression scores, even after the analysis controlled for comorbid axis I diagnoses of depression and anxiety disorders, suggests that, at least with respect to depressive symptoms, concomitant use of antidepressants as used in this patient population was not fully effective. Because we do not have data on duration or dose of treatment with antidepressants, this lack of efficacy may be due to suboptimum dosing or inadequate duration of treatment with antidepressants. Alternatively, the addition of antidepressants to second-generation antipsychotics may not be effective in treating depression among patients with schizophrenia. This issue can be addressed only in a randomized controlled clinical trial of adjunctive antidepressant use in depressed patients with schizophrenia who are taking second-generation antipsychotics.

The efficacy of antidepressant treatment among patients with schizophrenia has been an issue of considerable discussion. It is confounded by the fact that depressive symptoms among patients with schizophrenia may reflect demoralization or be subsyndromal. On the basis of a stringent definition of DSM-IV diagnosis of depression, 60 percent of patients with schizophrenia have an episode of major depression at some point in their illness course ( 36 ). Depression has been associated with an increased risk of relapse, poor social adjustment, and suicide ( 10 , 36 , 37 , 38 ). The evidence with respect to the benefits of adding antidepressants to antipsychotic medication for treatment of depressive symptoms among stable outpatients with schizophrenia has been mixed ( 10 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 ).

Unlike concomitant use of antidepressants or anxiolytics with antipsychotic medications, the use of mood stabilizers other than lithium and the use of sedatives were associated with more severe illness as indicated by higher PANSS scores. The association of use of these mood stabilizers with higher positive symptom scores suggests that these adjunctive medications are being used to treat patients with more positive symptoms. There are no randomized controlled studies of the persistent benefits of adjunctive divalproex compared with antipsychotic monotherapy after treatment of an acute exacerbation of schizophrenic illness.

A primary finding with respect to antipsychotic polypharmacy was that individuals who were treated with more than one antipsychotic medication had a lower neurocognitive composite score. It is possible that the association of antipsychotic polypharmacy with lower neurocognitive scores was a treatment side effect, perhaps caused by an increase in anticholinergic side effects. It is also possible that patients with more severe cognitive problems were more likely to be treated by antipsychotic polypharmacy, perhaps because of more partial adherence problems.

Although there is clear evidence that anticholinergic medications are effective in the treatment and prevention of acute extrapyramidal side effects ( 45 , 46 ), the need for long-term anticholinergic use among patients receiving antipsychotics is less clear ( 47 , 48 ). Therefore, assessing the side effect liability of such an intervention is critical. Our finding of greater neurocognitive impairment among patients with schizophrenia who were treated with anticholinergics is consistent with prior reports that anticholinergic agents impair several domains of cognitive functioning, including attention, declarative memory, verbal memory, and spatial working memory ( 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 ).

Although we do not know whether antipsychotic polypharmacy is a cause or a result of the neurocognitive impairment, the association of poor neurocognitive functioning with both antipsychotic polypharmacy and anticholinergic medications has important clinical implications. Evidence suggests that cognitive functioning is a core part of the pathology of schizophrenia ( 56 , 57 ), and those cognitive problems may persist even when psychotic symptoms are in remission ( 58 ). These cognitive deficits may cause more social and vocational disability than positive or negative symptoms and may play a role in relapse and rehospitalization ( 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 ).

Many of the concomitant prescribing patterns in treating patients with schizophrenia with persistent psychosis, anxiety, depression, and cognitive deficits are not robustly supported by evidence in the literature. Therefore, such prescribing is likely driven by inadequate response to monotherapy or unmet treatment needs among these patients. The data presented in this study suggest that better treatments for the depression, anxiety, and cognitive deficits of patients with schizophrenia need to be developed. In addition, the most frequent concomitant prescribing practices should be tested empirically in randomized controlled clinical trials.

Methodological limitations

The primary limitations of this study are that the data are cross-sectional and correlational. Patient assignment to drug treatment was naturalistic, and correlations between various concomitant psychotropic medications and clinical status may be due to confounding variables. Another major limitation is that we did not have information about duration of treatment or dosage of baseline medications and therefore could not draw meaningful conclusions about the efficacy of such interventions. This could only be done in randomized controlled clinical trials of these interventions. In addition, patients willing to enter a clinical trial such as CATIE and clinicians referring such patients may not be representative of all treated individuals with schizophrenia and their clinicians. An additional limitation is that for a small percentage of cases, medication history may not have been verified by a treating clinician or by medical record. A final limitation of the study is that we did not report concomitant nonpsychotropic medications, some of which are commonly used and have high atropine equivalence factors.

Conclusions

Use of concomitant psychotropic medications to treat patients with schizophrenia is prevalent, despite little information in regard to efficacy and liabilities associated with polypharmacologic interventions. Concomitant use of psychotropic medications in the treatment of schizophrenia is associated with diverse factors, including age, race, gender, persistent depression, concurrent anxiety and depressive disorder diagnoses, severity of illness, functional impairment, and neurocognitive impairment.

Acknowledgments

This article is based on results from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness project, supported by contract NO1-MH-90001 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). The project was carried out by principal investigators from the University of North Carolina, Duke University, the University of Southern California, the University of Rochester, and Yale University in association with Quintiles, Inc.; the program staff of the Division of Interventions and Services Research of NIMH; and investigators from 56 sites in the United States (CATIE Study Investigators Group). AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals L.P., Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Janssen Pharmaceutica Products, L.P., Eli Lilly and Company, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Pfizer, Inc., and Zenith Goldline Pharmaceuticals, Inc., provided medications for the studies. Details about the CATIE Study Investigators Group are available at www.catie.unc.edu/schizophrenia/locations.html#clinicalsitelocation list.

1. Tempier RP, Pawliuk NH: Conventional, atypical, and combination antipsychotic prescriptions: a 2-year comparison. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 64:673-679, 2003Google Scholar

2. Botts S, Hines H, Littrell R: Antipsychotic polypharmacy in the ambulatory care setting, 1993-2000. Psychiatric Services 54:1086, 2003Google Scholar

3. Fourrier A, Gasquet I, Allicar MP, et al: Patterns of neuroleptic drug prescription: a national cross-sectional survey of a random sample of French psychiatrists. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 49:80-86, 1999Google Scholar

4. Ito C, Kubota Y, Sato M: A prospective survey on drug choice for prescriptions for admitted patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 53(suppl):35-40, 1999Google Scholar

5. Keks NA, Altson K, Hope J, et al: Use of antipsychotics and adjunctive medications by an inner urban community psychiatric service. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 33:896-901, 1999Google Scholar

6. Rittmannsberger H, Meise U, Schauflinger K, et al: Polypharmacy in psychiatric treatment: patterns of psychotropic drug use in Austrian psychiatric clinics. European Psychiatry 14:33-40, 1999Google Scholar

7. Tapp A, Wood AE, Secrest L, et al: Combination antipsychotic therapy in clinical practice. Psychiatric Services 54:55-59, 2003Google Scholar

8. Hardy P, Payan C, Bisserbe JC, et al: Anxiolytic and hypnotic use in 376 psychiatric inpatients. European Psychiatry 14:25-33, 1999Google Scholar

9. Wolkowitz OM, Pickar D: Benzodiazepines in the treatment of schizophrenia: a review and reappraisal. American Journal of Psychiatry 148:714-726, 1991Google Scholar

10. Levinson DF, Umapathy C, Mustaq M: Treatment of schizoaffective disorder and schizophrenia with mood symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1138-1148, 1999Google Scholar

11. Stahl SM: Antipsychotic polypharmacy, part I: therapeutic option or dirty little secret? Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60:425-426, 1999Google Scholar

12. Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al: Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. New England Journal of Medicine 353:1209-1223Google Scholar

13. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon MB, et al: Structured Clinical Interview for Axes I and II DSM IV Disorders—Patient Edition (SCID-I/P). New York, Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1996Google Scholar

14. Kay SR, Fiszbeing, Opler DR: The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 13:261-276, 1987Google Scholar

15. Heinrichs DW, Hanlon ET, Carpenter WT: The Quality of Life Scale: an instrument for rating the schizophrenic deficit syndrome. Schizophrenia Bulletin 10:388-398, 1984Google Scholar

16. Lehman A: A quality of life interview for the chronically mentally ill. Evaluation and Program Planning 11:51-62, 1988Google Scholar

17. Barnes TR: A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. British Journal of Psychiatry 154:672-676, 1989Google Scholar

18. Guy W: Abnormal involuntary movements, in ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Edited by Guy W. DHEW ADM-76-338. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1976Google Scholar

19. Simpson GM, Angus JWS: A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 212:11-19, 1970Google Scholar

20. Addington D, Addington J, Maticka-Tyndale E: A depression rating scale for schizophrenics. Schizophrenia Research 3:247-251, 1996Google Scholar

21. Keefe RS, Mohs RC, Bilder RM, et al: Neurocognitive assessment in the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) project schizophrenia trial: development, methodology, and rationale. Schizophrenia Bulletin 29:45-55, 2003Google Scholar

22. Ereshefsky L: Pharmacologic and pharmacokinetic considerations in choosing an antipsychotic. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60(suppl 10):20-30, 1999Google Scholar

23. Stahl SM, Grady MM: A critical review of atypical antipsychotic utilization: comparing monotherapy with polypharmacy and augmentation. Current Medicinal Chemistry 11:313-327, 2004Google Scholar

24. Ascher-Svanum H, Kennedy JS, Lee D, et al: The rate, pattern, and cost of use of antiparkinsonian agents among patients treated for schizophrenia in a managed care setting. American Journal of Managed Care 10:20-24, 2004Google Scholar

25. Buchanan RW, Kreyenbuhl J, Zito JM, et al: Relationship of the use of adjunctive pharmacological agents to symptoms and level of function in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:1035-1043, 2002Google Scholar

26. Magliano L, Fiorillo A, Guarneri M, et al: Prescription of psychotropic drugs to patients with schizophrenia: an Italian national survey. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 60:513-522, 2004Google Scholar

27. Galletly CA, Tsourtos G: Antipsychotic drug doses and adjunctive drugs in the outpatient treatment of schizophrenia. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry 9(2):77-80, 1997Google Scholar

28. Citrome L, Jaffe A, Levine J, et al: Use of mood stabilizers among patients with schizophrenia, 1994-2001. Psychiatric Services 53:1212, 2002Google Scholar

29. Glick ID, Zaninelli R, Chuanchieh H: Patterns of concomitant psychotropic medication use during a 2-year study comparing clozapine and olanzapine for the prevention of suicidal behavior. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 65:679-685, 2004Google Scholar

30. Casey DE, Daniel DG, Wassef AA, et al: Effect of divalproex combined with olanzapine or risperidone in patients with an acute exacerbation of schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 28:182-192, 2003Google Scholar

31. Wassef AA, Dott SG, Harris A, et al: Randomized placebo controlled pilot study of divalproex sodium in treatment of acute exacerbation of chronic schizophrenia: clinical and economic implications. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 20:357-361, 2000Google Scholar

32. Tiihonen J, Hallikainen T, Ryynanen OP, et al: Lamotrigine in treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a randomized placebo-controlled crossover trial. Biological Psychiatry 54:1241-1248, 2003Google Scholar

33. Zisook S, McAdams LA, Kuck J, et al: Depressive symptoms in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1736-1743, 1999Google Scholar

34. Glazer WM, Morgenster H, Doucette J: Race and tardive dyskinesia among outpatients at a CMHC. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:38-42, 1994Google Scholar

35. Kreyenbuhl J, Zito JM, Buchanan RW, et al: Racial disparity in the pharmacological management of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 29:183-193, 2003Google Scholar

36. Martin RL, Cloninger CR, Guze SB, et al: Frequency and differential diagnosis of depressive syndromes in schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 46:9-13, 1985Google Scholar

37. Herz MI, Melville C: Relapse in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 137:801-805, 1980Google Scholar

38. Roy A: Depression, attempted suicide, and suicide in patients with chronic schizophrenia. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 9:193-206, 1986Google Scholar

39. Siris SG, Bermanzohn PC, Mason SE, et al; Maintenance imipramine therapy for secondary depression in schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:109-115, 1994Google Scholar

40. Siris SG, Morgan V, Fagerstrom R, et al: Adjunctive imipramine in the treatment of postpsychotic depression. Archives of General Psychiatry 44:533-539, 1987Google Scholar

41. Hogarty GE, McEvoy JP, Ulrich RF, et al: Pharmacotherapy of impaired affect in recovering schizophrenic patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:29-41, 1995Google Scholar

42. Prusoff BA, Williams DH, Weissman MM, et al: Treatment of secondary depression in schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 36:569-575, 1979Google Scholar

43. Becker RE: Implications of the efficacy of thiothixene and a chlorpromazine-imipramine combination for depression in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 140:208-211, 1983Google Scholar

44. Johnson DAW: A double-blind trial of nortriptyline for depression in chronic schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry 139:97-101, 1981Google Scholar

45. Bezchhilbnyk-Butler KZ, Remington GJ: Antiparkinsonian drugs in the treatment of neuroleptic-induced extrapyramidal symptoms. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 39:74-84, 1994Google Scholar

46. Winslow RS, Stiller V, Coons DJ, et al: Prevention of acute dystonic reactions in patients beginning high-potency neuroleptics. American Journal of Psychiatry 143:706-710, 1986Google Scholar

47. Rifkin A, Quitkin F, Kane J, et al: Are prophylactic antiparkinson drugs necessary? A controlled study of procyclidine withdrawal. Archives of General Psychiatry 35:483-489, 1978Google Scholar

48. Caradoc-Davies G, Menkes DB, Clarkson HO, et al: A study of the need for anticholinergic medication in patients treated with long-term antipsychotics. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 20:225-232, 1986Google Scholar

49. Gelenberg AJ, Van Putten T, Lavori PW, et al: Anticholinergic effects on memory: benztropine versus amantadine. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 9:180-185, 1989Google Scholar

50. Tune LE, Strauss ME, Lew MF, et al: Serum levels of anticholinergic drugs and impaired recent memory in chronic schizophrenic patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 139:1460-1462 1982Google Scholar

51. Perlick D, Stastny P, Katz I, et al: Memory deficits and anticholinergic levels in chronic schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 143:230-232, 1986Google Scholar

52. Sweeney JA, Keilp JG, Haas GL, et al: Relationships between medication treatments and neuropsychological test performance in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research 37:297-308, 1991Google Scholar

53. Tracy JI, Monaco C, Giovannetti T, et al: Anticholinergicity and cognitive processing in chronic schizophrenia. Biological Psychology 56:1-22, 2001Google Scholar

54. McGurk SR, Green MF, Wirshing WC, et al: Antipsychotic and anticholinergic effects on two types of spatial memory in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 68:225-233, 2004Google Scholar

55. Minzenberg MJ, Poole JH, Benton C, et al: Association of anticholinergic load with impairment of complex attention and memory in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:116-124, 2004Google Scholar

56. Goldberg TE, Ragland JD, Torrey EF, et al: Neuropsychological assessment of monozygotic twins discordant for schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 47:1066-1072, 1990Google Scholar

57. Gold JM, Harvey PD: Cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 16:295-312, 1993Google Scholar

58. Green MF: What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? American Journal of Psychiatry 153:321-330, 1996Google Scholar

59. Harvey PD, Howanitz E, Parrella M, et al: Symptoms, cognitive functioning, and adaptive skills in geriatric patients with lifelong schizophrenia: a comparison across treatment sites. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:1080-1086, 1998Google Scholar

60. Bellack AS, Gold JM, Buchanan RW: Cognitive rehabilitation for schizophrenia: problems, prospects, and strategies. Schizophrenia Bulletin 25:257-274, 1999Google Scholar