Olanzapine Versus Divalproex in the Treatment of Acute Mania

Abstract

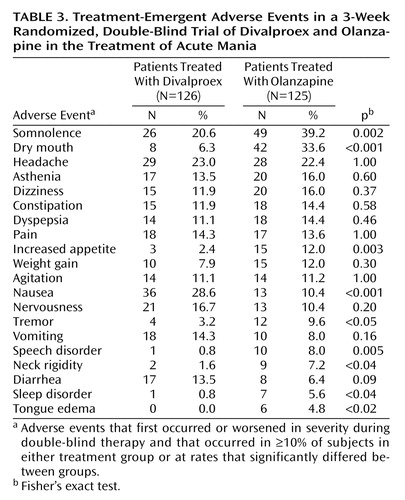

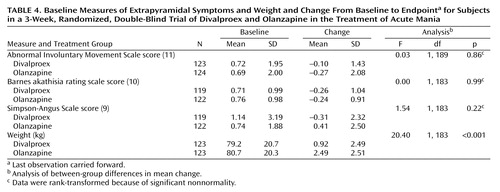

OBJECTIVE: The effects of olanzapine and divalproex for the treatment of mania were compared in a large randomized clinical trial. METHOD: A 3-week, randomized, double-blind trial compared flexibly dosed olanzapine (5–20 mg/day) to divalproex (500–2500 mg/day in divided doses) for the treatment of patients hospitalized for acute bipolar manic or mixed episodes. The Young Mania Rating Scale and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale were used to quantify manic and depressive symptoms, respectively. Safety was assessed with several measures. RESULTS: The protocol defined baseline-to-endpoint improvement in the mean total score on the Young Mania Rating Scale as the primary outcome variable. The mean Young Mania Rating Scale score decreased by 13.4 for patients treated with olanzapine (N=125) and 10.4 for those treated with divalproex (N=123). A priori categorizations defined response and remission rates: 54.4% of olanzapine-treated patients responded (≥50% reduction in Young Mania Rating Scale score), compared to 42.3% of divalproex-treated patients; 47.2% of olanzapine-treated patients had remission of mania symptoms (endpoint Young Mania Rating Scale ≤12), compared to 34.1% of divalproex-treated patients. The decrease in Hamilton depression scale score was similar in the two treatment groups. Completion rates for the 3-week study were similar in both groups. The most common treatment-emergent adverse events (incidence >10%) occurring more frequently during treatment with olanzapine were dry mouth, increased appetite, and somnolence. For divalproex, nausea was more frequently observed. The average weight gain with olanzapine treatment was 2.5 kg, compared to 0.9 kg with divalproex treatment. CONCLUSIONS: The olanzapine treatment group had significantly greater mean improvement of mania ratings and a significantly greater proportion of patients achieving protocol-defined remission, compared with the divalproex treatment group. Significantly more weight gain and cases of dry mouth, increased appetite, and somnolence were reported with olanzapine, while more cases of nausea were reported with divalproex.

Bipolar disorder affects approximately 1% of the U.S. population (1, 2). It represents a major public health concern, and the search for more effective and safe treatments is ongoing. In 1972, lithium was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of acute mania. More than 20 years elapsed before the next drug, divalproex, was approved. More recently, olanzapine, a thiobenzodiazepine previously approved for treatment of psychotic disorders, was the third drug approved by the FDA for treatment of acute mania.

Both divalproex (3, 4) and olanzapine (5, 6) have demonstrated acute antimanic efficacy in two placebo-controlled, parallel-group trials. Although placebo-controlled trials are instrumental in demonstrating efficacy of a drug, active comparison studies address more directly the relative benefits of efficacious treatments. The primary objective of the study reported here was to compare the efficacy of olanzapine versus divalproex in the treatment of acute mania over a 3-week period. Herein, we report the results of a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group study comparing olanzapine to divalproex.

Method

Patients

Patients aged 18 to 75 with a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder, manic or mixed episode, with or without psychotic features, were enrolled in this study. Clinical diagnoses were confirmed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, Patient Version. After the protocol was explained to them, patients provided written informed consent to participate in the study. A minimum total score of 20 on the Young Mania Rating Scale (7) was required at both the screening visit and on the day of random assignment to study groups (baseline). Patients with any of the following criteria were excluded: serious and unstable medical illness, DSM-IV substance dependence within the past 30 days (except nicotine or caffeine), documented history of intolerance to olanzapine or divalproex, and treatment with lithium, an anticonvulsant, or an antipsychotic medication within 24 hours of random assignment to study groups.

Study Design

This was a 3-week, double-blind, parallel-group study with a double-blind continuation phase of 44 weeks. This manuscript reports findings only for the 3-week acute phase. Patients were hospitalized at baseline and for at least the first week of double-blind treatment. All psychotropic medications (except benzodiazepines) were tapered and discontinued during the screening period.

Patients were randomly assigned to receive either olanzapine (5–20 mg/day) or divalproex (500–2500 mg/day). The initial daily doses were 15 mg/day of olanzapine and 750 mg/day of divalproex, consistent with the recommendations of the manufacturers. Investigators made dose adjustments primarily on the basis of clinical response but also on plasma levels and adverse events. Patients who did not tolerate the minimum dose level for treatment (5 mg/day olanzapine or 500 mg/day divalproex) were discontinued from participation in the study.

Plasma levels were obtained to evaluate whether divalproex trough levels were maintained within the targeted therapeutic range of 50–125 μg/ml. Assessment of olanzapine plasma levels has not been shown to be helpful in its clinical use. To maintain the blind, all patients randomly assigned to receive olanzapine had blood drawn, and sham “divalproex” plasma level results were reported. Despite the use of this procedure, all investigators at the clinical sites and at Lilly Research Laboratories remained blind to subjects’ treatment assignments. Blood was drawn from all patients on days 5, 7, and 21 and shipped to an independent reference laboratory; a coordinator at the reference laboratory was unblinded to treatment assignment. Divalproex levels below 35 μg/ml were reported as “well below target level,” levels from 35 to 49 μg/ml as “below target level,” levels from 126 to 150 μg/ml as “above target level,” and levels above 150 μg/ml as “well above target level.” For each report sent by the laboratory of an out-of-target-range plasma level for a divalproex-treated patient, a similar sham out-of-target-range report for divalproex was sent for a randomly selected olanzapine-treated patient at a different research center. Thus, if the investigator decided to change the medication dose on the basis of the “sham” divalproex plasma level for a patient taking olanzapine, increments or decrements affected only the number of placebo tablets given to that patient. This method ensured maintenance of the blind procedure.

Concomitant lorazepam use was restricted to a maximum dose of 2 mg/day, and administration was not allowed within 8 hours of the administration of a symptom rating scale. Benztropine was permitted to treat extrapyramidal symptoms up to a maximum of 2 mg/day throughout the course of the study. Benztropine was not allowed as prophylaxis for extrapyramidal symptoms.

Assessment

Severity of illness was assessed with the 11-item Young Mania Rating Scale (7) and the 21-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (8). These assessments were performed daily during the first week and weekly thereafter. A priori categorical definitions included symptomatic remission, defined as endpoint Young Mania Rating Scale total score ≤12, and clinical response, defined as ≥50% baseline-to-endpoint reduction in Young Mania Rating Scale total score. Safety was assessed by monitoring adverse events, as well as by monitoring laboratory test values, ECG results, vital signs, changes in weight, and scores on extrapyramidal symptoms rating scales (Simpson-Angus Scale [9], Barnes akathisia rating scale [10], and Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale [11]). Adverse events that originally occurred or worsened in severity during double-blind therapy were considered treatment emergent; these events were recorded and coded by using the FDA’s Coding Symbols for Thesaurus of Adverse Reaction Terms dictionary (12).

Statistical Methods

Patient data were analyzed on an intent-to-treat basis. Patients with a baseline and at least one postbaseline measurement were included in the analysis of mean improvement with the last observation carried forward.

Efficacy and extrapyramidal symptoms rating scale scores were evaluated by using analysis of variance. Rank-transformed data were analyzed, as appropriate, when significant nonnormality was found in the analysis of raw data. The models included terms for the fixed effects of treatment, investigator, and the treatment-by-investigator interaction. Models for analyses of subgroup data included terms for investigator, treatment, the subgroup, and the treatment-by-subgroup interaction. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare effects of the treatments on each Young Mania Rating Scale item. Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze treatment effects for completion rate, reason for discontinuation, categorical efficacy, treatment-emergent adverse events, and abnormalities in vital signs, ECG, and laboratory test results. Time to discontinuation, time to response, and time to symptomatic remission were assessed by using Kaplan-Meier estimated survival curves, and the curves for each treatment group were compared with the log-rank test.

The primary objective of the study was to assess the noninferiority of olanzapine compared to divalproex in the reduction (from baseline to endpoint) of manic symptoms as measured by the Young Mania Rating Scale total score (with the last observation carried forward) after 3 weeks of acute therapy. The assessment of noninferiority was planned as a one-tailed comparison (one-tailed 95% confidence interval [CI]) evaluating whether olanzapine was no worse than divalproex in reducing manic symptoms by a predefined amount. In this trial, olanzapine was considered noninferior only if the reduction in the Young Mania Rating Scale score was no more than 1.9 points less than the reduction associated with divalproex. This a priori margin of noninferiority was equivalent to 20% of the reduction in manic symptoms (9.5 points on the Young Mania Rating Scale) reported previously for divalproex therapy (3). The protocol was designed for approximately 325 patients per group to be enrolled. This number of subjects was needed to provide 80% power that the lower limit of the 95% one-sided CI for the difference in mean change in Young Mania Rating Scale total scores between the two treatment groups was greater than or equal to –1.9. The calculation assumed that 5% of patients would not have a postbaseline visit, that the expected mean change from baseline was –10.3 in the olanzapine group and –9.5 in the divalproex group, and that the common standard deviation was 13. A standard assessment of a statistical difference in symptom reduction by means of a two-tailed test of significance was planned with p<0.05 (superiority) and performed only after a significant assessment of noninferiority. This secondary assessment of statistical superiority after a significant assessment of noninferiority was made without penalty for multiple testing (13). An interim analysis of the last-observation-carried-forward change in the Young Mania Rating Scale total score was performed under the auspices of a data monitoring board. Analysis for the first 117 patients randomly assigned to treatment groups (59 olanzapine patients and 58 divalproex patients) resulted in a recommendation from the data monitoring board for early termination of enrollment after at least 200 total patients had been enrolled. The recommendation was based on the interim analysis finding of conditional power, derived by using the method of Lan and Wittes (14), in excess of 95% for the assessment of noninferiority. The final enrollment of 251 patients was a result of ethical considerations of allowance made to investigators to enroll patients already scheduled for screening after the data monitoring board had made its recommendation. The interim analysis employed a significance level (alpha) of 0.015. Adjusted alpha for the final analysis of the primary efficacy measure was calculated by using the method of Armitage et al. (15). Therefore, the final analysis with N=251 utilized a 95.76% one-tailed CI for noninferiority (or alpha=0.0412 for a two-tailed test of significance). Otherwise, cited p values are based on two-tailed tests with a significance level of 0.05.

Results

Patients

The baseline characteristics of the patients in each treatment group are summarized in Table 1. A total of 330 patients were screened and entered into the study across 48 sites in the United States. Seventy-nine patients were recruited into the study but were not randomly assigned to treatment groups. Of these 79 excluded patients, 28 met protocol exclusionary criteria, 35 refused to participate, 15 were excluded by investigators, and one additional patient was unable to be contacted after study entry. A total of 126 and 125 patients were randomly assigned to receive divalproex and olanzapine, respectively. There were no statistically significant differences in the demographic or illness characteristics between the two treatment groups. Response during the most recent episode to antipsychotic medications, lithium, or valproate occurred in 84.0% of the 206 patients for whom data were available (84 divalproex patients and 89 olanzapine patients); 79.9% of the 194 patients for whom data were available (77 divalproex patients versus 78 olanzapine patients) responded to either lithium or valproate during their most recent exposure. There were no significant treatment group differences in rates of completion of the 3-week acute phase of therapy between olanzapine-treated (N=86, 68.8%) and divalproex-treated (N=81, 64.3%) patients (p=0.50, Fisher’s exact test). Further, reasons for discontinuation did not differ significantly between groups with 9.6% (N=12) and 8.8% (N=11) of olanzapine-treated patients discontinuing because of adverse events or lack of efficacy, espectively, compared to 7.1% (N=9) (p=0.50, Fisher’s exact test) and 9.5% (N=12) (p=1.00, Fisher’s exact test) of patients treated with divalproex. Kaplan-Meier estimated time-to-discontinuation curves did not differ significantly between groups (χ2=0.57, df=1, p=0.45). By day 7, a total of 15 divalproex-treated patients and 14 olanzapine-treated patients had discontinued; by day 14, discontinuations totaled 28 patients for divalproex therapy and 29 patients for olanzapine therapy. Three patients treated with divalproex had no postbaseline assessment and were excluded from analyses of the Young Mania Rating Scale primary efficacy variable.

Treatment

Mean modal doses for olanzapine and divalproex were 17.4 mg/day and 1401.2 mg/day, respectively. Mean blood level of divalproex at scheduled sampling visits was 77.4 μg/liter (SD=27.8, N=108) at day 5; 82.1 μg/liter (SD=33.1, N=105) at day 7; and 83.9 μg/liter (SD=32.1, N=77) at day 21. A blood level of divalproex ≥50 μg/liter was achieved by 94 (87.0%) of 108, 91 (86.7%) of 105, and 68 (88.3%) of 77 patients at days 5, 7, and 21, respectively.

The groups did not differ significantly in use of allowed anticholinergic (12.8% versus 9.5%; p=0.43, Fisher’s exact test) or benzodiazepine (65.6% versus 65.9%; p=1.00, Fisher’s exact test) adjunctive medication for olanzapine and divalproex patients, respectively.

Efficacy

The mean improvement in the Young Mania Rating Scale total score was 13.4 points (SD=8.8) in the olanzapine treatment group and 10.4 points (SD=10.4) in the divalproex treatment group. The lower limit of the 95.76% one-tailed confidence interval for the assessment of noninferiority was 0.96, well in excess of the predefined –1.9 margin of therapeutic equivalence. Further, this 3.0 difference in mean Young Mania Rating Scale improvement favoring the olanzapine treatment group was statistically significant (F=4.92, df=1, 190, p<0.03) (Table 2). Baseline-to-endpoint (last observation carried forward) Young Mania Rating Scale total score improvement was significantly greater in the olanzapine group at day 2 (F=4.70, df=1, 190, p<0.04), day 14 (F=5.64, df=1, 190, p<0.02), and day 21 (F=4.92, df=1, 190, p<0.03) but not at day 1 and days 3–7. Mean improvement from baseline to endpoint (last observation carried forward) was significantly greater for olanzapine-treated patients on three of the individual Young Mania Rating Scale items: increased motor activity (χ2=4.30, df=1, p<0.04), sleep (χ2=8.21, df=1, p=0.004), and language–thought disorder (χ2=6.24, df=1, p<0.02). There was no significant between-group difference in mean improvement in any of the other eight individual Young Mania Rating Scale items.

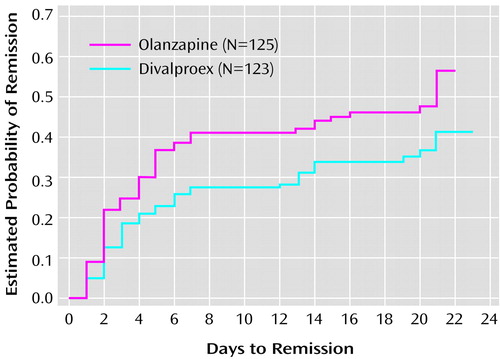

Response and Remission

Clinical response, based on ≥50% improvement in the Young Mania Rating Scale score at endpoint, was achieved by 54.4% of olanzapine-treated patients (N=68) and 42.3% of divalproex-treated patients (N=52) (p=0.058, Fisher’s exact test). However, among responders, the estimated time-to-response curves for the two treatment groups were significantly different (χ2=4.28, df=1, p<0.05), occurring more rapidly in the olanzapine group. The rates of symptomatic remission (endpoint Young Mania Rating Scale total score ≤12 ) were 47.2% for the olanzapine-treated patients (N=59) and 34.1% for the divalproex-treated patients (N=42) (p<0.04, Fisher’s exact test). The estimated time-to-remission curves for the two therapy groups were significantly different (χ2=4.45, df=1, p<0.04); the estimated 25th percentile for time to remission was 3 days for olanzapine patients and 6 days for divalproex patients (Figure 1).

Mean baseline-to-endpoint change in the Hamilton depression scale score was similar in the olanzapine-treated and the divalproex-treated patients (mean=–4.92, SD=7.22, and mean=–3.46, SD=6.40, respectively) (F=1.05, df=1, 188, p=0.31). Among the subset of patients with a Hamilton depression scale total score of 20 or more at baseline, the mean change at endpoint was –10.3 (SD=8.2) among 29 olanzapine-treated patients and –8.1 (SD=7.4) among 24 divalproex-treated patients (F=1.06, df=1, 51, p=0.31).

Efficacy in Psychotic and Nonpsychotic Subgroups

Differential results were found on the basis of the presence or absence of psychotic features (F=3.55, df=1, 247, p=0.06). Among patients without psychotic features, the improvement with olanzapine therapy (mean change from baseline=–14.1, SD=8.6) was 5.4 points greater than with divalproex therapy (mean change from baseline=–8.7, SD=8.5) (F=13.46, df=1, 107, p<0.001). In the subgroup with psychotic features, there was no statistically significant difference in improvement between the olazapine patients (mean change from baseline=–12.6, SD=9.0) and the divalproex patients (mean change from baseline=–12.8, SD=12.4) (F=0.98, df=1, 112, p=0.93).

Safety

Adverse events

Nine patients in the divalproex treatment group and 12 patients in the olanzapine treatment group discontinued treatment because of an adverse event. Table 3 lists treatment-emergent adverse events reported significantly more frequently in one treatment group compared to the other and/or reported by at least 10% of the patients in either treatment group.

Extrapyramidal symptom ratings

There were no significant differences between treatment groups in baseline-to-endpoint mean change in scores on the extrapyramidal symptoms rating scales (Table 4).

Vital signs

There were no statistically significant differences between treatment groups in the incidence rates of potentially clinically relevant changes in vital signs. Patients in the olanzapine treatment group had a significantly larger mean weight gain, compared to the patients in the divalproex treatment group (mean=2.5 kg, SD=2.5, and mean=0.9 kg, SD=2.5, respectively) (F=20.40, df=1, 188, p<0.001) (Table 4).

Laboratory measures

The only statistically significant differences between treatment groups in treatment-emergent abnormalities in laboratory measures occurred in the alanine aminotransferase/serum glutamic-pyruvic transferase (ALT/SGPT) value and the platelet count. Patients in the olanzapine treatment group had a significantly higher incidence of increased ALT/SGPT (based on reference range limits that were specific to age, ethnic origin, and sex categories and that ranged from >80 U/liter for Caucasian women between age 18 and 49 to >125 U/liter for Caucasian men between age 18 and 49) than patients in the divalproex treatment group (5.1% versus 0%, respectively) (p<0.03, Fisher’s exact test). The incidence of decreased platelet count (based on reference range limits that were specific to age, ethnic origin, and sex categories and that ranged from <151 × 109/liter for Caucasian women between age 18 and 49 down to <114 × 109/liter for non-Caucasian women between age 50 and 99) was significantly higher for divalproex-treated patients than for the olanzapine-treated patients (8.0% versus 0%, respectively) (p=0.001, Fisher’s exact test). There were no significant between-group differences in rates of treatment-emergent abnormalities in other chemistry, hematology, and ECG tests at endpoint.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the largest double-blind comparison of divalproex and olanzapine in the treatment of acute mania. Olanzapine-treated patients improved significantly more on the primary efficacy variable (Young Mania Rating Scale total score).

In a recent 4-week, placebo-controlled trial that used 15 mg/day of olanzapine as the starting dose (6), the mean reduction in the Young Mania Rating Scale score at week 3 (last observation carried forward) was 13.9 points, comparable to the 13.4-point reduction for olanzapine-treated patients in the current trial. Few available data address whether the 10.4-point mean improvement in the divalproex group is in line with expectations. A placebo-controlled valproate trial reported by Pope et al. (4) used the Young Mania Rating Scale as the primary outcome variable, but the results may not be directly comparable to those of the current trial because the Pope et al. study was a smaller, single-center trial that enrolled lithium-refractory and/or intolerant patients. In that 3-week study, 17 valproate-treated patients had a mean improvement on the Young Mania Rating Scale of 11.4 points, slightly higher than that observed in the current study.

It is noteworthy that the reported average divalproex plasma levels in a study by Bowden et al. (3) were 77 μg/ml at day 8 and 93 μg/ml at day 21, compared to 82 μg/ml at day 7 and 84 μg/ml at day 21 in the current trial. The slightly higher mean levels at endpoint in the Bowden et al. trial may reflect differences in methods; in that study, six upward titrations of divalproex were mandated, unless the subject’s blood level was more than 150 μg/ml or contravening side effects developed. In the study by Pope et al. (4), blood levels of valproate were not reported. However, the authors indicated that most of the clinical improvement was observed within 1–4 days of achieving serum levels of at least 50 mg/liter.

A report recently presented by Zajecka et al. (16) described another study comparing divalproex sodium (N=63) to olanzapine (N=57) in the treatment of acute mania. Zajecka and collaborators used a starting loading dose of 20 mg/kg per day for divalproex sodium (mean maximum dose=2115 mg/day) and 10 mg/day for olanzapine (mean maximum dose=14.7 mg/day). As in the present study, more improvement in the Young Mania Rating Scale was observed during olanzapine treatment than during divalproex treatment. However, unlike our findings, the difference observed by Zajecka et al. was not statistically significant. This difference may be explained by the smaller study group size of 120 patients, compared to 251 in the present study. The results indicated a reduction of 17.2 points for olanzapine and 14.8 for divalproex (p=0.21) on the Young Mania Rating Scale from baseline to 21 days of treatment. Dropout rates due to adverse events were similar between treatments, and more individual adverse event terms—including somnolence, weight gain, rhinitis, edema, and speech disorder—were observed significantly more often during treatment with olanzapine.

In the current study, olanzapine produced greater improvement, compared to divalproex, as measured by the change in score on the Young Mania Rating Scale at days 2, 14, and 21. It is possible that the brief early separation reflects slower achievement of therapeutic dosing for divalproex than for olanzapine. Divalproex dosing was titrated in accordance with the manufacturer’s recommendation, starting at 750 mg on day 1 and was thereafter adjusted on the basis of clinical response and serum levels. Improvement in the early stages of divalproex therapy appears more likely if the serum level has reached at least 45 μg/ml (17). Therefore, standard dose initiation at 750 mg/day potentially achieves efficacy less promptly than divalproex “loading” strategies, with first day doses of 20–30 mg/kg. Several open studies have supported the feasibility and utility of loading (18–21), and one double-blind trial focusing on safety and tolerability found more efficacy for loaded than for standard titration after 3 days of treatment (22). Based on the findings of Hirschfeld et al. (22), olanzapine’s transient separation during week 1 may have been less likely if divalproex had been loaded.

It is interesting to note that olanzapine’s antimanic advantage in this 3-week study cannot be solely ascribed to treatment of psychotic symptoms. Without correcting for multiple comparisons, the treatments separated on only three of the 11 items of the Young Mania Rating Scale, with olanzapine superior on sleep, increased motor activity, and language–thought disorder items. Furthermore, Young Mania Rating Scale improvement among these psychotic patients was similar between the two treatments, and olanzapine treatment produced significantly greater improvement for the manic patients without psychotic features. A treatment-by-subgroup interaction in Young Mania Rating Scale improvement was observed when patients were categorized on the basis of presence or absence of psychotic features. Among olanzapine-treated patients, mean Young Mania Rating Scale improvement was similar in the psychotic and nonpsychotic subgroups (mean change of –12.6 and –14.1 points, respectively). Among divalproex-treated patients, Young Mania Rating Scale score reduction was greater in the psychotic subgroup (–12.8 points) than in the nonpsychotic subgroup (–8.7 points). To our knowledge, previous controlled trials of divalproex have not reported whether antimanic efficacy varied according to the presence or absence of psychotic features.

Conclusions

During a 3-week, randomized, double-blind trial of treatment for acute mania that compared flexibly dosed olanzapine versus divalproex, olanzapine produced greater improvement in symptoms of mania as rated by the Young Mania Rating Scale. In analyses using a priori clinically meaningful definitions of remission and response, olanzapine was statistically superior for remission and had superiority approaching significance for clinical response, compared with divalproex. Both drugs appeared to be well tolerated, and the two treatment groups had similar rates of discontinuation because of adverse events. However, more adverse events, including weight gain, occurred significantly more frequently during treatment with olanzapine than with divalproex. Although in this trial the primary outcome favored olanzapine, the selection of pharmacological treatment should consider both safety and efficacy parameters as well as patient-specific considerations.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the following institutions and individuals who participated in this clinical trial: Jay Amsterdam, M.D., University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; George Bartzokis, M.D., Little Rock Veterans Affairs Medical Center, North Little Rock, Ark.; Louise Dabiri-Beckett, M.D., IPS Research Company, Oklahoma City; Gary Booker, M.D., IPS Research Company, Shreveport, La.; Ron Brenner, M.D., St. John’s Episcopal Hospital, Far Rockaway, N.Y.; David Brown, M.D., Community Clinical Research, Inc., Austin, Tex.; Timothy Byrd, M.D., Charter Springs Behavioral Clinic, Ocala, Fla.; Franca Centorrino, M.D., McLean Hospital, Belmont, Mass.; James Chou, M.D., Bellevue Hospital, New York; Anthony Claxton, M.D., and Hermant Patel, M.D., University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City; Lori Davis, M.D., Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Tuscallosa, Ala.; Jose E. De La Gandara, M.D., North Broward Neurological Institute Memory Disorder Center, Pompano Beach, Fla.; G. Michael Dempsey, M.D., Memorial Hospital, Albuquerque, N.M.; Rif El-Mallakh, M.D., University of Louisville School of Medicine, Louisville, Ky.; Louis Fabre, M.D., Fabre Research Clinics, Houston; David Feifel, M.D., University of California at San Diego Medical Center, San Diego; Brent Forester, M.D., Mental Health Center of Greater Manchester, Manchester, N.H.; Arthur Freeman III, M.D., Louisiana State University Medical Center, Shreveport, La.; Mark Frye, M.D., UCLA Neuropsychiatric Institute and Hospital, Los Angeles; Alan Green, M.D., Massachusetts Mental Health Center, Boston; Sanjay Gupta, M.D., Psychiatric Network, P.C., Olean, N.Y.; Robert Horne, M.D., Lake Meade Hospital, Las Vegas; Fuad Issa, M.D., Clinical Research Center of Northern Virginia, Falls Church, Va.; Robert Jamieson, M.D., Psychiatric Consultants, P.C., Nashville, Tenn.; Christopher Kelsey, M.D., San Diego Center for Research, San Diego; Louis Ari Kopolow, M.D., Associated Psychotherapy Centers, Gaithersburg, Md.; Jeff Mitchell, M.D., Laureate Psychiatric Clinic and Hospital, Tulsa, Okla.; Cesar Munoz, M.D., University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Ala.; Fred Petty, M.D., Ph.D., Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Dallas; Michael, Plopper, M.D., Mesa Vista Hospital, San Diego; Joanchim Raese, M.D., Knollwood Psychiatric and Chemical Dependency Center of Charter Hospital, Murietta, Calif.; Jeffery Rausch, M.D., Medical College of Georgia, Augusta, Ga.; Robert Riesenberg, M.D., Atlanta Center for Medical Research, Decatur, Ga.; Leon Rubenfaer, M.D., Harbor Oaks Hospital, Farmington Hills, Mich,; John Schmitz, M.D., Midwest Psychiatric Consultants, P.C., Kansas City, Mo.; Taylor Segraves, M.D., Ph.D., MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland; Philip Seibel, M.D., Contemporary Behavioral Research, L.L.C., Washington, D.C.; G. Michael Shehi, M.D., Mountain View Hospital, Gladsden, Ala.; Marshall Thomas, M.D., University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Denver; Kathleen Toups, M.D., Bay Area Research Institute, Lafayette, Calif.; Dan Wilson, M.D., Pauline Warfield Lewis Center, Cincinnati; Tai P. Yoo, M.D., Mercy Hospital, Detroit; and John Zajecka, M.D., Rush Presbyterian St. Lukes, Chicago.

|

|

|

|

Received Jan. 16, 2001; revision received Nov. 2, 2001; accepted Dec. 17. 2001. From Lilly Research Laboratories; the Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School and McLean Hospital, Belmont, Mass.; UCLA Neuropsychiatric Institute and Hospital, Los Angeles; National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, Md.; University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas; and Stanford University, Stanford, Calif. Address reprint requests to Dr. Tohen, Lilly Research Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN 46285; [email protected] (e-mail). Sponsored by Lilly Research Laboratories.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier Estimates of Time to Remission for Subjects in a 3-Week Randomized, Double-Blind Trial of Divalproex and Olanzapine in the Treatment of Acute Maniaa

aRemission was defined as endpoint score ≤12 on the Young Mania Rating Scale. Significantly shorter time to remission in the olanzapine group (χ2=4.45, df=1, p<0.04, log-rank test).

1. Tohen M, Angst J: Epidemiology of bipolar disorder, in Textbook in Psychiatric Epidemiology, 2nd ed. Edited by Tsuang MT, Tohen M. New York, John Wiley & Sons (in press)Google Scholar

2. Kessler RC, Rubinow DR, Holmes C, Abelson JM, Zhao S: The epidemiology of DSM-III-R bipolar I disorder in a general population survey. Psychol Med 1997; 27:1079-1089Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Bowden CL, Brugger AM, Swann AC, Calabrese JR, Janicak PG, Petty F, Dilsaver SC, David JM, Rush AJ, Small JG, Garza-Trevino ES, Risch C, Goodnick PJ, Morris DD: Efficacy of divalproex versus lithium and placebo in the treatment of mania. JAMA 1994; 271:918-924Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Pope HG Jr, McElroy SL, Keck PE Jr, Hudson JI: Valproate in the treatment of acute mania: a placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:62-68Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Tohen M, Sanger TM, McElroy SL, Tollefson GD, Chengappa KNR, Daniel DG, Petty F, Centorrino F, Wang R, Grundy SL, Greaney MG, Jacobs TG, David SR, Toma V (Olanzapine HGEH Study Group): Olanzapine versus placebo in the treatment of acute mania. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:702-709Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Tohen M, Jacobs TG, Grundy SL, Banov MC, McElroy SL, Janicak PG, Zhang F, Toma V, Francis J, Sanger T, Tollefson GD, Breier A: Efficacy of olanzapine in acute bipolar mania: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:841-849Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA: A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry 1978; 133:429-435Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Hamilton M: Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1967; 6:278-296Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Simpson GM, Angus JWS: A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1970; 212:11-19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Barnes TRE: A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry 1989; 154:672-676Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76-338. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976, pp 534-537Google Scholar

12. Coding Symbols for Thesaurus of Adverse Reaction Terms, 5th ed. Rockville, Md, US Dept of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, 1995Google Scholar

13. Points to Consider on Biostatistical/Methodological Issues Arising From Recent CPMP Discussions on Licensing Applications: Superiority, Non-Inferiority, and Equivalence. London, Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products of the European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products, 1999Google Scholar

14. Lan KKG, Wittes J: The B-value: a tool for monitoring data. Biometrics 1988; 44:579-585Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Armitage P, McPherson CK, Copas JC: Statistical studies of prognosis in advanced breast cancer. J Chronic Dis 1969; 22:343-360Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Zajecka J, Weisler R, Sommerville KW: Divalproex sodium versus olanzapine for the treatment of mania in bipolar disorder, in Proceedings of the 39th Annual Meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. Nashville, Tenn, ACNP, 2000, p 257Google Scholar

17. Bowden CL, Janicak PG, Orsulak P, Swann AC, Davis JM, Calabrese JR, Goodnick P, Small JG, Rush AJ, Kimmel SE, Risch SC, Morris DD: Relation of serum valproate concentration to response in mania. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:765-770Link, Google Scholar

18. Keck PE Jr, McElroy SL, Tugrul KC, Bennett JA: Valproate oral loading in the treatment of acute mania. J Clin Psychiatry 1993; 54:305-308Medline, Google Scholar

19. McElroy SL, Keck PE Jr, Tugrul KC, Bennett JA: Valproate as a loading treatment in acute mania. Neuropsychobiology 1993; 27:146-149Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. McElroy SL, Keck PE Jr, Stanton SP, Tugrul KC, Bennett JA, Strakowski SM: A randomized comparison of divalproex oral loading versus haloperidol in the initial treatment of acute psychotic mania. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57:142-146Medline, Google Scholar

21. Grunze H, Schlosser S, Walden J: [New perspectives in the treatment of bipolar depression.] Psychopharmakotherapie 1999; 6:53-59 (German)Google Scholar

22. Hirschfeld RM, Allen MH, McEvoy JP, Keck PE Jr, Russell JM: Safety and tolerability of oral loading divalproex sodium in acutely manic bipolar patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:815-818Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar