Functional Impairment in Patients With Schizotypal, Borderline, Avoidant, or Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to compare psychosocial functioning in patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder and patients with major depressive disorder and no personality disorder. METHOD: Patients (N=668) were recruited by the four clinical sites of the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study. The carefully diagnosed study groups were compared on an array of domains of psychosocial functioning, as measured by the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation—Baseline Version and the Social Adjustment Scale. RESULTS: Patients with schizotypal personality disorder and borderline personality disorder were found to have significantly more impairment at work, in social relationships, and at leisure than patients with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder or major depressive disorder; patients with avoidant personality disorder were intermediate. These differences were found across assessment modalities and remained significant after covarying for demographic differences and comorbid axis I psychopathology. CONCLUSIONS: Personality disorders are a significant source of psychiatric morbidity, accounting for more impairment in functioning than major depressive disorder alone.

Impairment in psychosocial functioning is integral to the concept of a personality disorder. Only when personality traits are sufficiently inflexible and maladaptive to cause significant functional impairment (or subjective distress) is normal personality style distinguished from a pathological personality disorder. DSM-IV codified a requirement for impairment in its criterion C of the general diagnostic criteria for a personality disorder, which states that “the enduring pattern [of inner experience and behavior, i.e., personality] leads to clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning” (p. 633).

Since 1980, when attention was focused on personality disorders by placing them on a separate diagnostic axis (axis II) of DSM-III’s multiaxial system, a number of studies have documented functional impairment in patients with personality disorders compared with patients with no personality disorder or with other axis I disorders. Most of these studies inferred functional impairment from various sociodemographic statuses believed to reflect psychosocial functioning, such as educational attainment, marital status, or employment. A majority of these studies found that patients with personality disorders were more likely than those without or with other disorders to be separated, divorced, or never married (1–11) and to have had more unemployment, frequent job changes, or periods of disability (4, 5, 7, 9, 12, 13). Only rarely were they found to be less educated (1, 12). Fewer studies have examined quality of functioning, but in those that have, poorer social functioning or interpersonal relations (2, 4, 5, 7, 13–18) and poorer work functioning or occupational satisfaction and achievement (2, 4, 7, 14–16, 19–22) were found among patients with personality disorders compared with others. On measures of global functioning, most studies have shown significant global functional impairment for patients with personality disorders (4, 5, 13–15, 17–19, 23–33).

Other than the studies that have used the Global Assessment Scale, the Health-Sickness Rating Scale, or DSM-IV’s global assessment of functioning (axis V), few efforts have been made to systematically assess and quantify social functioning and impairment in patients with personality disorders (other than borderline personality disorder) or to compare one personality disorder to another. The purpose of the present study was to examine levels of functioning in a broad array of psychosocial domains in patients with DSM-IV schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder by means of standardized instruments, both interviewer-administered and self-report. Levels of typical functioning in the month before intake were assessed, and the four personality disorders were compared with each other and with a group of patients with current major depressive disorder and no personality disorder. We hypothesized that personality disorders would differ from each other in the degree of associated functional impairment and that patients with severe (i.e., schizotypal or borderline) personality disorders would have more functional impairment than patients with less severe (i.e., avoidant or obsessive-compulsive) personality disorders or with major depressive disorder.

Method

Subjects

Participants 18 to 45 years of age were recruited primarily from clinical services affiliated with each of the four recruitment sites of the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study. In all, 668 patients with at least one of four personality disorders or with major depression and no personality disorder were included. All were previously or currently in treatment: 42.7% (N=285) were outpatients in mental health settings, 12.0% (N=80) were psychiatric inpatients, 5.4% (N=36) were from other mental health or medical settings, and 40.0% (N=267) were self-referred.

Participants were prescreened to determine age eligibility and treatment status or history and to exclude patients with active psychosis, acute substance intoxication or withdrawal or other confusional states, or a history of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. All participants signed written informed consent after the research procedures had been fully explained.

The 668 patients were assigned to one of five diagnostic groups: schizotypal personality disorder (N=86, 12.9% of the total), borderline personality disorder (N=175, 26.2%), avoidant personality disorder (N=157, 23.5%), obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (N=153, 22.9%), and major depressive disorder (N=97, 14.5%). The majority of the patient group were women (63.6%, N=425), white (75.4%, N=504), and from Hollingshead and Redlich social classes I or II (38.0%, N=229 of 603). They were roughly equally distributed across the age range included in the study (mean age=32.7 years, SD=8.1).

Assessment

All patients were interviewed by experienced master’s- or doctoral-level raters with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (34) and the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (35). Raters were trained by using live or videotaped interviews under the supervision of the senior author of the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (M.C.Z.) at McLean Hospital. The four personality disorder diagnoses had good interrater and test-retest reliabilities (schizotypal: kappa=1.0 and 0.64, respectively; borderline: kappa=0.68 and 0.69; avoidant: kappa=0.68 and 0.73; obsessive-compulsive: kappa=0.71 and 0.74) (36). For the assignment of patients to the study groups, diagnoses obtained from the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders received convergent support from the results of either of two contrasting approaches to axis II diagnosis: the self-report Schedule for Nonadaptive and Adaptive Personality (37) or an independent clinician’s rating on the Personality Assessment Form (6).

To assess psychosocial functioning, interviewers administered the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation—Baseline Version (38). The Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation includes questions to assess functioning in employment; household duties; student work; interpersonal relationships with parents, siblings, spouse/mate, children, other relatives, and friends; recreation; and three ratings of global functioning: global satisfaction, global social adjustment, and the DSM-IV axis V global assessment of functioning. Most areas of functioning were rated on 5-point scales of severity (1=no impairment, high level of functioning or very good functioning; 2=no impairment, satisfactory level of functioning or good functioning; 3=mild impairment or fair functioning; 4=moderate impairment or poor functioning; and 5=severe impairment or very poor functioning). Global assessment of functioning is rated on a 100-point scale, with 100 indicating the highest possible level of functioning. Ratings were made for each patient’s typical functioning in the month before evaluation. In addition, subjects completed the self-report Social Adjustment Scale (39). Reliability of the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation social functioning scales (38, 40) and the Social Adjustment Scale (41) has been previously established.

More detailed descriptions of the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study rationale, recruitment, subject demographics, diagnostic assessments, reliability, and assessment of axis I comorbidity are available elsewhere (36, 42, 43).

Analyses

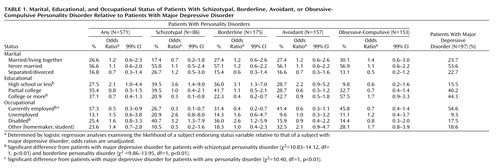

The likelihood of patients showing achievement or impairment in marital status, educational attainment, and occupational status was compared between each of the personality disorder groups and the major depressive disorder group by using logistic regression. Odds ratios with 99% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated that compared the major depressive disorder group with each individual personality disorder group as well as with the personality disorder group as a whole.

Means and standard deviations on each of the social functioning scales of the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation were calculated for the month before intake. The general linear models procedure (analysis of covariance) was used to compare mean functioning by study group assignment. In order to determine whether significant differences in functional impairment persisted after accounting for demographic differences and comorbidity, we controlled for gender, age, minority status, and comorbid axis I psychopathology. Duncan post hoc tests were done to determine specific differences between personality disorder groups and the major depressive disorder group. Corresponding analyses were conducted on the Social Adjustment Scale scores.

Logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine the likelihood that the personality disorder groups had severe impairment in any domain of functioning in the month before baseline compared with the major depressive disorder group. A separate model was done for each of the measures from the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation. The analyses controlled for the effects of gender, age, minority status, and axis I psychopathology. Goodness-of-fit for each model was assessed by using Hosmer and Lemeshow’s C statistic (44). Odds ratios and 99% confidence intervals from the models are presented.

All statistical analyses were conducted by using SAS Version 6.12 (45). Statistical significance was set at p<0.01.

Results

Functional Status

Table 1 shows that there were no differences among the personality disorder groups and the major depressive disorder group on the proportion of subjects married or living with someone, separated or divorced, or never married. Patients with schizotypal personality disorder and borderline personality disorder had over three times the odds of having only a high school education relative to the major depressive disorder patients and less than half the odds of having graduated college. In addition, patients with schizotypal personality disorder and borderline personality disorder were less frequently currently employed and had two to over three times the odds of being disabled (Table 1).

Interviewer-Rated Impairment

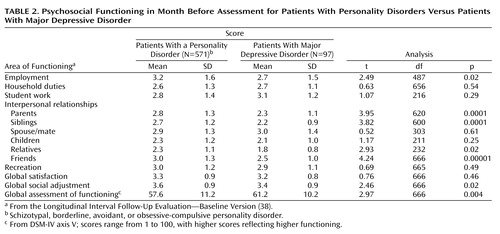

The mean level of impairment across the areas of psychosocial functioning measured during the month before assessment for patients with personality disorders ranged from 2.3 to 3.6, while the corresponding ratings for patients with major depressive disorder ranged from 1.8 to 3.4 (Table 2). The average rating of 2.9 indicates a general mild-to-moderate level of impairment or fair to poor functioning in patients with personality disorders. Relative to that of patients with major depressive disorder, significantly greater impairment in functioning was found in patients with personality disorders for social relations with parents, siblings, and friends and for global assessment of functioning.

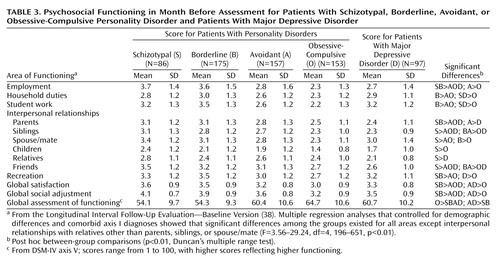

Table 3 shows the mean levels of impairment in psychosocial functioning during the month before baseline assessment at intake for the four personality disorder groups and the major depressive disorder group. Patients with schizotypal personality disorder and borderline personality disorder consistently were rated as exhibiting greater functional impairment than were patients with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder or major depressive disorder. Patients with avoidant personality disorder were intermediate. Multiple regression analyses controlling for demographic differences and comorbid axis I disorders showed that significant differences between the groups existed in all areas of psychosocial functioning in the previous month, except for interpersonal relationships with relatives (other than parents, siblings, or spouse/mate). High percentages of patients with schizotypal (98.8%), borderline (98.3%), avoidant (96.2%), and obsessive-compulsive (87.6%) personality disorder and major depressive disorder (92.8%) exhibited moderate (or worse) impairment or poor (or worse) functioning in at least one area or received a global assessment of functioning rating of 60 or below in the month before intake.

Self-Reported Impairment

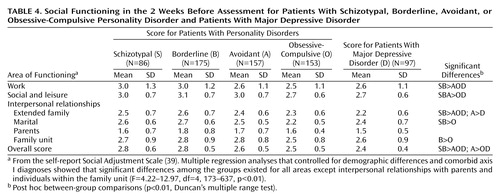

Table 4 shows self-reported impairment for the 2 weeks before assessment. Consistent with the interviewer ratings, patients with schizotypal personality disorder and borderline personality disorder rated themselves as significantly more impaired on all individual domains of functioning and overall than those with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder and major depressive disorder; patients with avoidant personality disorder remained intermediate.

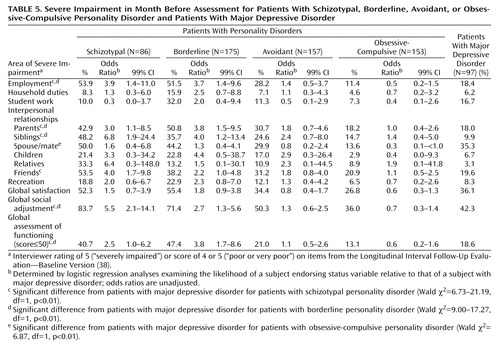

Ratings of Severe Impairment

Since average ratings of impairment in psychosocial functioning tended to be moderate among patients with personality disorders, we sought to determine how often personality disorders were associated with severe levels of impairment in contrast to major depressive disorder. Table 5 shows odds ratios with 99% confidence intervals comparing each of the four personality disorder groups with the major depressive disorder group on the proportion of subjects rated by interviewers as severely impaired (score=5) or with poor or very poor functioning (score=4 or 5) on the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation scales during the previous month. On approximately half of the measures, the odds of patients with schizotypal personality disorder or borderline personality disorder having severe impairment were significantly greater than were those of patients with major depressive disorder. Patients with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder were rated as severely impaired less frequently than those with major depressive disorder in many areas (odds ratios less than 1.0), although these differences were significant only for social relationships with spouse/mate, for which patients with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder had one-third the odds of having severe impairment.

Discussion

This study is among the first to document and quantify the extent of functional impairment found in patients with different types of personality disorders in contrast to patients having an impairing axis I disorder. Our results indicate that functional impairment due to personality disorders can be reflected by sociodemographic statuses as well as by qualitative differences in functional performance. Our failure to find differences in marital status between patients with personality disorders and those with major depressive disorder may be due to the relatively low rate of married patients in all the study groups. Older patients, in general, were more likely to be married (analyses not shown), and our study group had an upper age range limit of 45 years.

Our results supported our hypothesis that patients with personality disorders that are traditionally believed to be more severe have greater degrees of functional impairment than do patients with less severe personality disorders or major depressive disorder. Our finding the same pattern of results through self-report and interview data suggests that the excess impairment in severe personality disorders is not accounted for by interviewer expectation or bias. Patients with schizotypal personality disorder and borderline personality disorder had greater impairment on virtually every measure of impairment than did patients with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder or major depressive disorder, regardless of whether the assessment was interview-based or by patient self-report, even after covarying for comorbid axis I psychopathology. It is of interest that although we controlled for the effects of gender in our regression models, in checking our analyses, we found no significant gender effects, implying that men and women are equally impaired from their axis II disorders. Our findings are especially noteworthy given the growing appreciation for the degree and persistence of limitations in functioning of patients with major depressive disorder. Impairment due to major depressive disorder has been found to be comparable to that of patients with chronic medical illnesses such as diabetes and arthritis (46, 47), and major depressive disorder is the leading cause worldwide of years lived with disability according to the Global Burden of Disease Study (48).

Although there are no Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation data on patients with personality disorders in the existing literature with which to compare our findings, our results are consistent with those of other investigators indicating poor social (2, 4, 5, 7, 13–18) and work (2, 4, 7, 14–16, 19–22) functioning among patients with personality disorders. The mean DSM-IV axis V global assessment of functioning rating of 54 for patients with borderline personality disorder and schizotypal personality disorder is similar to that reported in outpatient populations by Frances et al. (23), Barasch et al. (25), and Nurnberg et al. (27). The rating is higher than that of personality disorder patients upon admission to the hospital as reported by Tucker et al. (49), Plakun et al. (24), Mehlum et al. (31), Najavits and Gunderson (50), and Levy et al. (33). At the time of admission, a patient’s functioning might be expected to be at a low ebb. At other times of outpatient treatment (as was the case for the majority of our patients), functioning might be expected to have improved.

Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder was associated with the least overall functional impairment among the personality disorders. Some might question whether some of these individuals should have received a personality disorder diagnosis at all. However, even in this group almost 90% had moderate or worse impairment or poor or worse functioning in at least one area or received a global assessment of functioning rating of 60 or less at intake, which suggests that patients with less severe personality disorders may not have widespread functional impairment but do have at least one area of significant impairment that could warrant a personality disorder diagnosis.

It should be recognized that all information about functioning obtained in this study came from the patients themselves. Therefore, it is possible that certain types of psychopathology may have influenced reporting, e.g., patients with borderline personality disorder may tend to exaggerate their difficulties, while those with major depressive disorder may minimize them. However, the argument that a depressive state leads to an overreporting of personality psychopathology would suggest that depressed patients may also exaggerate their impairments (51). Furthermore, assessments by semistructured interview, such as those conducted for personality disorders and psychosocial functioning in this study, are believed to reduce reporting distortions by careful clinical “cross-examination” and by eliciting examples of traits, behaviors, and functioning (52). Finally, possible reporting biases are less obvious in the case of schizotypal personality disorder, which was associated with considerable functional impairment.

These results underscore the impression of many clinicians that personality disorders are an overlooked and underappreciated source of psychiatric morbidity. Comorbid personality disorders may, in fact, account for much of the morbidity attributed to axis I disorders in research and clinical practice. Personality disorders appear likely to be a significant public health problem, and more work is needed to document the persistence of functional impairment in patients with personality disorders and its costs to patients, their families, and society. Treatment approaches with an emphasis on psychosocial rehabilitation may be needed (53–55) to mitigate the pernicious effects of personality disorders on functioning.

Acknowledgments

The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study is being conducted with the participation of investigators from the following sites: Brown University Department of Psychiatry, Providence, R.I.; the Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons and New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York; the Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School and McLean Hospital, Boston; the Department of Psychology, Texas A&M University, College Station, Tex.; and the Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine and Yale Psychiatric Institute, New Haven, Conn.

|

|

|

|

|

Received Dec. 1, 2000; revision received July 5, 2001; accepted Aug. 18, 2001. From the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study. Address reprint requests to Dr. Skodol, Box 121, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1051 Riverside Dr., New York, NY 10032. Supported by grants from NIMH (MH-50837, MH-50838, MH-50839, MH-50840, MH-50850); an NIMH grant to Dr. McGlashan (MH-01654); and grants from the Borderline Personality Disorder Research Foundation (Drs. McGlashan, Grilo, and Sanislow).

1. Soloff PH, Ulrich RF: Diagnostic interview for borderline patients: a replication study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 38:686-692Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Torgersen S: Genetic and nosological aspects of schizotypal and borderline personality disorders: a twin study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:546-554Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Pfohl B, Stangl D, Zimmerman M: The implications of DSM-III personality disorders with major depression. J Affect Disord 1984; 7:309-318Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Drake RE, Vaillant GE: A validity study of axis II of DSM-III. Am J Psychiatry 1985; 142:553-558Link, Google Scholar

5. McGlashan TH: Schizotypal personality disorder: Chestnut Lodge follow-up study, VI: long-term follow-up perspectives. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43:328-334Google Scholar

6. Shea MT, Glass DR, Pilkonis PA, Watkins J, Docherty JP: Frequency and implications of personality disorders in a sample of depressed inpatients. J Personal Disord 1987; 1:27-42Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Modestin J, Villiger C: Follow-up study on borderline versus nonborderline personality disorders. Compr Psychiatry 1989; 30:236-244Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Zimmerman M, Coryell W: DSM-III personality disorder diagnosis in a nonpatient sample: demographic correlates and comorbidity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:682-689Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Swartz M, Blazer D, George L, Winfield I: Estimating the prevalence of borderline personality disorder in the community. J Personal Disord 1990; 4:257-272Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Nestadt G, Romanoski AJ, Chahal R, Merchant A, Folstein MF, Gruenberg EM, McHugh PR: An epidemiological study of histrionic personality disorder. Psychol Med 1990; 20:413-422Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Nakao K, Gunderson JG, Phillips KA, Tanaka N, Yorifuji K, Takaishi J, Nishimura T: Functional impairment in personality disorders. J Personal Disord 1992; 6:24-33Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Reich J, Yates W, Nduaguba M: Prevalence of DSM-III personality disorders in the community. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1989; 24:12-16Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Paris J, Brown R, Nowlis D: Long-term follow-up of borderline patients in a general hospital. Compr Psychiatry 1987; 28:530-535Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Pope HG, Jonas JM, Hudson JI, Cohen BM, Gunderson JG: The validity of borderline personality disorder: a phenomenologic, family history, treatment, and long-term follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983; 40:23-30Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Andreoli A, Gressot G, Aapro N, Tricot L, Gognalons MY: Personality disorders as a predictor of outcome. J Personal Disord 1989; 3:307-321Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Shea MT, Pilkonis PA, Beckham E, Collins JF, Elkin I, Sotsky SM, Docherty JP: Personality disorders and treatment outcome in the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:711-718Link, Google Scholar

17. Noyes R Jr, Reich J, Christiansen J, Suelzer M, Pfohl B, Coryell W: Outcome of panic disorder: relationship to diagnostic subtypes and comorbidity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:809-818Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Turner SM, Beidel DC, Borden JW, Stanley MA, Jacob RG: Social phobia: axis I and II correlates. J Abnorm Psychol 1991; 100:102-106Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. McGlashan TH: The borderline syndrome, I: testing three diagnostic systems. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983; 40:1311-1318Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Reich J, Troughton E: Comparison of DSM-III personality disorders in recovered depressed and panic disorder patients. J Nerv Ment Dis 1988; 176:300-304Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Rice DP, Kelman S, Miller LS, Dunmeyer S: The Economic Costs of Alcohol and Drug Abuse and Mental Illness:1985. Washington, DC, United States Department of Health and Human Services, Alcohol, Drug Abuse and Mental Health Administration, 1990Google Scholar

22. Casey PR, Tyrer P: Personality disorder and psychiatric illness in general practice. Br J Psychiatry 1990; 156:261-265Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Frances A, Clarkin JF, Gilmore M, Hurt SW, Brown R: Reliability of criteria for borderline personality disorder: a comparison of DSM-III and the Diagnostic Interview for Borderline Patients. Am J Psychiatry 1984; 141:1080-1084Link, Google Scholar

24. Plakun EM, Burkhardt PE, Muller JP: Fourteen-year follow-up of borderline and schizotypal personality disorders. Compr Psychiatry 1985; 26:448-455Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Barasch A, Frances A, Hurt S, Clarkin J, Cohen S: The stability and distinctness of borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1985; 142:1484-1486Link, Google Scholar

26. Klass ET, DiNardo PA, Barlow DH: DSM-III-R personality disorders in anxiety disorder patients. Compr Psychiatry 1989; 30:251-258Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Nurnberg HG, Raskin M, Levine PE, Pollock S, Prince R, Siegel O: BPD as a negative prognostic factor in anxiety disorders. J Personal Disord 1989; 3:205-216Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Pilkonis PA, Heape CL, Ruddy J, Serrao P: Validity in the diagnosis of personality disorders: the use of the LEAD standard. Psychol Assess 1991; 3:46-54Crossref, Google Scholar

29. Herbert JD, Hope DA, Bellack AS: Validity of the distinction between generalized social phobia and avoidant personality disorder. J Abnorm Psychol 1992; 102:332-339Crossref, Google Scholar

30. Nace EP, Davis CW, Gaspari JP: Axis II comorbidity in substance abusers. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:118-120Link, Google Scholar

31. Mehlum L, Friis S, Irion T, Johns S, Karterud S, Vaglum P, Vaglum S: Personality disorders 2-5 years after treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1991; 84:72-77Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Johnson JG, Williams JBW, Goetz RR, Rabkin JG, Remien RH, Lipsitz JD, Gorman JM: Personality disorders predict onset of axis I disorders and impaired functioning among homosexual men with and at risk of HIV infection. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:350-357Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Levy KN, Becker DF, Grilo CM, Mattanah JJF, Garnet KE, Quinlan DM, Edell WS, McGlashan TH: Concurrent and predictive validity of the personality disorder diagnosis in adolescent inpatients. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1522-1528Link, Google Scholar

34. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-P). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1996Google Scholar

35. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Sickel AE, Yong L: The Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (DIPD-IV). Belmont, Mass, McLean Hospital, 1996Google Scholar

36. Zanarini MC, Skodol AE, Bender D, Dolan R, Sanislow C, Schaefer E, Morey LC, Grilo CM, Shea MT, McGlashan TH, Gunderson JG: The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: reliability of axis I and axis II diagnoses. J Personal Disord 2000; 14:291-299Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Clark LA: Schedule for Nonadaptive and Adaptive Personality (SNAP). Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1993Google Scholar

38. Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman B, Nielsen E, Endicott J, McDonald-Scott P, Andreasen NC: The Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation: a comprehensive method for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:540-548Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Weissman M, Bothwell S: The assessment of social adjustment by patient self-report. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976; 33:1111-1115Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Warshaw MG, Keller MB, Stout RL: Reliability and validity of the Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation for assessing outcome of anxiety disorders. J Psychiatr Res 1994; 28:531-545Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Edwards DW, Yarvis RM, Mueller DP, Zingale HC, Wagman WJ: Test-taking and the stability of adjustment scales: can we assess patient deterioration? Evaluation Quarterly 1978; 2:275-292Crossref, Google Scholar

42. Gunderson JG, Shea MT, Skodol AE, McGlashan TH, Morey LC, Stout RL, Zanarini MC, Grilo CM, Oldham JM, Keller MB: The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: development, aims, design, and sample characteristics. J Personal Disord 2000; 14:300-315Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. McGlashan TH, Grilo CM, Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Shea MT, Morey LC, Zanarini MC, Stout RL, Oldham JM, Keller MB: The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: baseline patterns of DSM-IV axis I/II and II/II diagnostic co-occurrence. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000; 102:256-264Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S: Applied Logistic Regression. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1989Google Scholar

45. SAS Version 6.12. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1996Google Scholar

46. Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, Burnam MA, Rogers W, Daniels M, Berry S, Greenfield S, Ware J: The functioning and well-being of depressed patients: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA 1989; 262:914-919Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Hayes RD, Wells KB, Sherbourne CD, Rogers W, Spritzer K: Functioning and well-being outcomes of patients with depression compared with chronic general medical illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:11-19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Murray CJL, Lopez AD (eds): The Global Burden of Disease: A Comprehensive Assessment of Mortality and Disability from Disease, Injuries, and Risk Factors in 1990 and Projected to 2020. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1996Google Scholar

49. Tucker L, Bauer SF, Wagner S, Harlem D, Sher I: Long-term hospital treatment of borderline patients: a descriptive outcome study. Am J Psychiatry 1987; 144:1443-1448Link, Google Scholar

50. Najavits L, Gunderson JG: Better than expected: improvements in borderline personality disorder in a 3-year prospective outcome study. Compr Psychiatry 1995; 36:296-302Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51. Hirschfeld RMA, Klerman GL, Clayton PJ, Keller MB, McDonald-Scott P, Larkin BH: Assessing personality: effects of the depressive state on trait assessment. Am J Psychiatry 1983; 140:695-699Link, Google Scholar

52. Loranger AW, Lenzenweger MF, Gartner AF, Susman VL, Herzig J, Zammit GK, Gartner JD, Abrams RC, Young RC: Trait-state artifacts and the diagnosis of personality disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:720-728Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53. Links PS: Psychiatric rehabilitation model for borderline personality disorder. Can J Psychiatry 1993; 38(suppl 1):35-38Google Scholar

54. Paris J: Borderline Personality Disorder: A Multidimensional Approach. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994Google Scholar

55. Gunderson JG: Borderline Personality Disorder: A Clinical Guide. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 2000Google Scholar