Assessing the Competence of Persons With Alzheimer’s Disease in Providing Informed Consent for Participation in Research

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The capacity of persons with Alzheimer’s disease or other neuropsychiatric disorders for giving consent to participate in research has come under increasing scrutiny. While instruments for measuring abilities related to capacity have been developed, how they should be used to categorize subjects as capable or incapable is not clear. A criterion validation study was carried out to help address this question. METHOD: The authors measured the ability of 37 subjects with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease and 15 elderly comparison subjects to provide consent for participation in a hypothetical clinical trial. Using the judgment of three experts as the criterion standard, the authors performed a receiver operator characteristic analysis for the capacity ability measures from the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool—Clinical Research Version. The results were compared with categorizations of capacity status that were based on normative values. RESULTS: While most comparison subjects scored perfectly on all measures of the competence assessment tool, the majority of the group with Alzheimer’s disease showed significant decision-making impairment. Thresholds based on normative values resulted in 84% (N=31) of the Alzheimer’s disease subjects being rated as incapable on at least one ability; thresholds based on expert judgment resulted in 62% (N=23) failing to meet cutoff scores on at least one ability. CONCLUSIONS: Even relatively mild Alzheimer’s disease significantly impairs consent-giving capacity. But differentiating capable from incapable subjects remains an issue despite the aid of standardized tools. More research is needed to understand the relationship between subject factors (performance on ability measures) and categorical judgments about their capacity.

Informed consent requires a voluntary and informed decision by a competent person. Because many neuropsychiatric disorders may directly affect a person’s decision-making capacity, ethical concerns persist over ensuring informed consent in psychiatric research (1). The National Bioethics Advisory Commission, for instance, would require an independent capacity evaluation of potentially impaired subjects who enter any study regarded as having greater than minimal risk (2). The American Psychiatric Association disseminated guidelines for researchers regarding this issue in 1998 (3). At least one psychiatric journal now requires its authors to document their capacity assessment procedures (4).

Alzheimer’s disease is identified by the National Bioethics Advisory Commission as one of the “mental disorders that may affect decisionmaking capacity” (2). The current practice involving most potential subjects with probable Alzheimer’s disease involves a “double consent” procedure for clinical trials, i.e., consent or assent from the Alzheimer’s disease subject along with a surrogate consent (5). Even though this practice is acceptable in many situations, there are strong reasons to develop reliable and valid methods to assess the decision-making capacity of persons with Alzheimer’s disease (and other disorders that impair cognitive functioning). First, the reliance on surrogate consent becomes ethically more problematic as the risks of a study increase or the potential benefits decrease (2). The exciting prospects of developing novel approaches to treatment—for instance, gene transfer-based therapies or cerebral cell transplants—will create a need for close ethical scrutiny regarding the decision-making abilities of Alzheimer’s disease subjects. Both the risks and benefits of such novel approaches may be especially uncertain, making surrogate consent more problematic. Second, as the field of Alzheimer’s disease therapeutics moves in the direction of early detection and prevention, more subjects with relatively mild illness will be invited to participate in both therapeutic and nontherapeutic research. While many affected individuals surely will be capable of giving consent, some will not be capable even while they maintain their “social graces” and their expressive abilities. There needs to be a reliable and valid method of distinguishing the two groups, especially given the likely acceleration of Alzheimer’s disease clinical research in the context of increased ethical and policy concerns.

The assessment of a person’s capacity for consent can be conceptualized as a two-stage process. First, the abilities relevant to decision making are measured. A reliable and valid instrument is important for this step, and strides have been made in the past several years in this regard, with the MacArthur instruments being the best tested in both treatment and research consent contexts (6–9). Others have used different instruments to measure the abilities related to capacity of Alzheimer’s disease subjects to consent to treatment (10). However, an instrument score reflects only one factor in the capacity evaluation. The second step is the clinical judgment that incorporates the subject’s performance factors along with important contextual factors—the main one being the risk/benefit calculus—to yield a dichotomous decision. The first task requires an appraisal of the cognitive abilities relevant to capacity and is focused on the patient/subject; the second judges this information in a specific context to yield a categorical decision regarding “capacity.” Ideally, a study of the capacity of Alzheimer’s disease subjects to provide informed consent informs both steps.

There are three options for connecting the results of a standardized instrument with the real world of clinical decision making. One method is to set or establish an a priori threshold for performance on the instrument itself (11). This relies heavily on the theoretical assumptions and values of the investigators. A second method is to determine a statistically defined (such as deviations from a standard distribution) cutoff by using the performance of healthy comparison subjects as a normative standard to distinguish between “impaired versus unimpaired” (6, 12) or “competent versus incompetent” (10) persons. Using this approach, researchers have shown that even mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease has significant impact on treatment consent capacity (10). This method gives valuable comparison information, but the cutoff points generated remain arbitrary. A third approach employs the judgments of expert capacity evaluators as a provisional gold standard (13–16).

This study focuses on research consent rather than treatment consent. We report here a criterion validation study that used the judgments of three experts as a provisional gold standard and compare the results with competency categorizations based on normative values for a group of subjects with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s dementia.

Method

The subjects in this study were recruited from the outpatient Geriatric Neurology and Psychiatry Clinic at the Monroe Community Hospital, an affiliate of the University of Rochester. The potential subject pool was created by applying two criteria to all new evaluations in that clinic during the preceding year: 1) a diagnosis of probable Alzheimer’s disease based on the criteria of the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (17) and 2) a Mini-Mental State score of 18 or above. On the basis of previous studies on treatment consent in subjects with Alzheimer’s disease (10), the Mini-Mental State cutoff was set low enough so that the study group would likely contain both capable and incapable subjects. Of the 148 subjects meeting these criteria, contact was established with 79 patients. The remaining potential subjects (N=69) were not contacted for several reasons, such as they were unreachable despite repeated attempts, their treating physicians advised against it, or they lived too far away (reflecting the large number of consultations done by this regional clinic). Of the 79 contacted, 38 refused, and four were unable to complete the interview, thus yielding 37 completed interviews with usable data. Differences in mean age and years of education between participants and nonparticipants were not significant (78.7 versus 79.6 years and 13.8 versus 13.0 years, respectively), whereas the mean Mini-Mental State score of the participants was slightly higher (23.5 versus 22.3) (t test in which equal variance is not assumed: t=2.3, df=59.2, p=0.02). The 15 comparison subjects for the study were caretakers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease from the same clinic. It was reasoned that such a group would not only be comparable in age and education as the Alzheimer’s disease subjects but also have personal experience regarding Alzheimer’s disease to draw from in answering the capacity interview. Previous studies with comparably impaired Alzheimer’s disease patients showed that 15 comparison subjects were sufficient to show significant differences in performance between the two study groups (10).

This study was approved by the University of Rochester’s Research Subjects Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant after a full explanation of the study. Whenever there was any doubt about the subject’s capacity, the primary caregiver’s simultaneous written consent was also obtained.

Almost all of the interviews were conducted at the subjects’ homes. All subjects in the study were administered the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool—Clinical Research Version (8, 9). It has excellent content validity, and to our knowledge it is the only instrument that assesses the full range of abilities relevant to capacity for giving informed consent to participate in research. It is a second-generation instrument based on the experience of a multicenter study of treatment capacity (18) and has been used in persons with schizophrenia (9) and major depression (8) but not dementia.

The MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool—Clinical Research Version contains 21 pertinent disclosure elements of informed consent, each given a rating of 0 (inadequate), 1 (partial), or 2 (adequate). The items are structured under the four-abilities model of competence discussed by Grisso and Appelbaum (12). These abilities are 1) understanding of disclosed information about the nature of the research project and its procedures (13 items); 2) appreciation of the effects of research participation (or failure to participate) on subjects’ own situations (three items); 3) reasoning about participation (four items); and 4) ability to communicate a choice (one item) (8). Data on the ability to communicate a choice will not be presented, since only one person in the entire study group failed this portion of the interview.

The MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool—Clinical Research Version is a semistructured interview that needs to be adapted to reflect the content of individual protocols; for the present study, the subjects were asked to consider a relatively low-risk, hypothetical, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial of a new medication for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Even though the current practice of informed consent in Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials of this sort involves “double consent,” the familiar nature of the research design and the relatively transparent risk-potential benefit balance of such a trial, it was felt, would facilitate the interpretation of the data. The process of adapting the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool—Clinical Research Version to a particular situation is discussed in further detail elsewhere (8); the version used for this study is available from the authors. Comparisons of mean scores on the competence assessment tool of the Alzheimer’s disease and comparison subjects were done by using two-tailed t tests in which equal variances were not assumed.

As part of their training, research staff members who administered and scored the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool—Clinical Research Version were trained by receiving feedback on six audiotaped interviews from Paul S. Appelbaum, M.D., one of the developers of the tool. The first 10 Alzheimer’s disease subjects were scored independently by the research assistant on the project and the principal investigator (S.Y.H.K.); an additional 10 Alzheimer’s disease subjects were reviewed over the remaining duration of the study to yield the 20 cases used for measurement of interscorer reliability. For the measurement of interexaminer reliability, eight Alzheimer’s disease subjects were interviewed twice, each time by different interviewers, within 2 weeks of each other; the second interviewer was masked from the results of the first interview. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were used as the measure of reliability (19).

For the expert judgment validation, three psychiatrists (two geriatric psychiatrists, one emergency room psychiatrist) who were aware of the four-abilities model of capacity but blind to the competence assessment tool scores independently listened to 18 audiotaped interviews of Alzheimer’s disease subjects. The 18 cases were selected by the principal investigator (S.Y.H.K.) to represent a wide range of performance on the competence assessment tool. The expert clinicians were asked, “Given the kind of study involved (with its risks and potential benefits), does this person have enough abilities to give informed consent for him or herself?,” and were given four options: definitely capable, probably capable, probably incapable, and definitely incapable. For the purposes of analyses, “definitely” and “probably” were collapsed in order to establish two dichotomous categories. Each of the 18 Alzheimer’s disease subjects selected for this validation study was assigned a status of “capable” or “incapable” according to consensus (three out of three) or majority (two out of three) vote. Analyses were then performed to generate receiver operator characteristic curves for each of the abilities measured by the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool—Clinical Research Version. Areas under the curve were calculated, and optimal cutoff points were estimated for each ability.

These optimal cutoff points for each of the abilities were then used to categorize the entire group of Alzheimer’s disease subjects (N=37) as either capable or incapable of giving consent. For comparison purposes, cutoff points based on normative values were established by using a method similar to those employed by other researchers (10, 13, 20), namely, setting the cutoff point at some statistical level, in this case two standard deviations below the comparison group mean. McNemar’s test (two-sided exact test) was used to compare the results of the two methods.

Results

There were no significant differences in age, education, or gender distributions between the two groups. The mean ages of the Alzheimer’s disease and comparison groups were 78.7 years (SD=5.8) and 75.5 years (SD=4.7), respectively. Both groups were relatively well educated, with a mean of 13.8 (SD=3.2) total years of education for the Alzheimer’s disease group and 13.9 years (SD=2.1) for the comparison subjects. Both groups had a similar proportion of women (60% and 67%, respectively). At the time of the study interview, the mean Mini-Mental State score for the Alzheimer’s disease subjects was 22.9 (SD=3.8, range=16–28), whereas for the comparison subjects it was 28.9 (SD=1.1, range=24–30) (t test in which equal variance is not assumed: t=8.0, df=49.81, p<0.001).

Interscorer (same subject interview scored by two scorers, N=20) and interexaminer (two separate interviews of the same subject by different interviewers, N=8) reliability were calculated for the abilities of understanding, appreciation, and reasoning. Interscorer reliability was high (understanding: ICC=0.94 [F=31.5, df=19, 19, p<0.001]; appreciation: ICC=0.90 [F=18.0, df=19, 19, p<0.001], reasoning: ICC=0.80 [F=9.2, df=19, 19, p<0.001]). Interexaminer reliability was lower (understanding: ICC=0.77 [F=7.5, df=7, 7, p=0.008]; appreciation: ICC=0.68 [F=5.2, df=7, 7, p=0.02]; reasoning: ICC=0.82 [F=10.2, df=7, 7, p=0.003]).

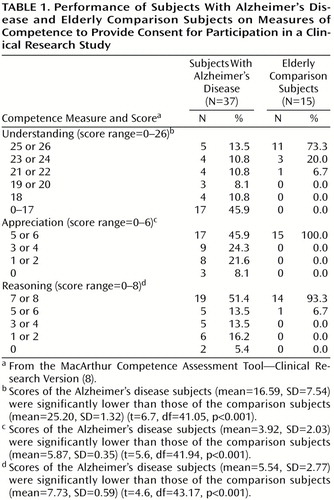

On each of the abilities measured by the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool—Clinical Research Version, the Alzheimer’s disease group performed significantly worse than the comparison group (Table 1). For the 15 comparison subjects, the task appeared to be quite easy: most scored perfectly on the abilities of understanding (10 subjects [67%] had a score of 26), appreciation (13 subjects [87%] had a score of 6), and reasoning (13 subjects [87%] had a score of 8).

How can these numbers be used to categorize the Alzheimer’s disease subjects as capable or incapable? This question served as the rationale for the expert judgment validation portion of the study. All three clinicians agreed on the capacity status of 12 of the 16 subjects. (Two cases were not used in this concordance calculation because two of the three clinicians each had technical difficulties with one tape and thus gave judgments on 17 cases each. However, each of the two cases missing one clinician judgment still showed agreement between the other two clinicians’ judgments; therefore, they were included in the receiver operator characteristic analysis.) The pairwise kappa scores were 0.49 between clinicians 1 and 2 (p=0.05), 0.76 between clinicians 1 and 3 (p=0.002), and 0.76 between clinicians 2 and 3 (p=0.002). The clinicians found that 10 of the 18 Alzheimer’s disease subjects reviewed were capable of giving consent to participate in the hypothetical clinical trial.

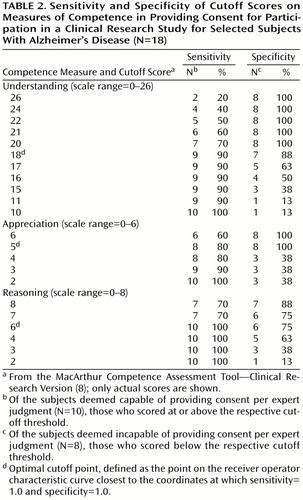

The receiver operator characteristic analysis for the understanding, appreciation, and reasoning abilities from the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool—Clinical Research Version were performed, with the categorizations of capacity status based on expert clinician judgment used as the gold standard (Table 2, receiver operator characteristic curves not shown). The areas under the curve for understanding, appreciation, and reasoning as tests of capacity status were 0.90 (95% confidence interval [CI]=0.73–1.07), 0.86 (95% CI=0.66–1.05), and 0.88 (95% CI=0.70–1.06), respectively. The optimal cutoff point for each ability measure was defined as the point on the receiver operator characteristic curve closest to the coordinates at which sensitivity=1.0 and specificity=1.0. The cutoff points for understanding, appreciation, and reasoning were 18 (sensitivity=90%, specificity=88%), 5 (sensitivity=80%, specificity=100%), and 6 (sensitivity=100%, specificity=75%), respectively.

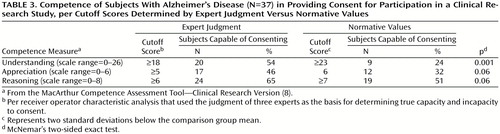

Table 3 shows the application of these cutoff points to the entire Alzheimer’s disease group of 37 subjects along with the results of categorizing capacity status on the basis of normative values. When cutoff scores based on expert judgment were used, 62% (N=23 of 37) were rated as incapable on at least one of the abilities measured by the competence assessment tool. When cutoff scores based on normative values (two standard deviations below the comparison group mean) were used, 84% (N=31 of 37) were found incapable on at least one measure (McNemar Test, p=0.008, two-sided exact test). All 15 comparison subjects would have met the cutoffs of the expert judgment method and thus would have been found capable.

Discussion

The main goal of this study was to address a key issue in competency research, namely how to translate data on decisional impairment into categorical judgments about competence, by comparing two methods. This is a relatively new area of research, and the results should be seen as preliminary with some limitations. Our study group was small, as reflected in the discreteness of the receiver operator characteristic curves. The use of a hypothetical scenario is an accepted methodology in competency research (9, 10), but it is not as realistic as an actual consent process. The gold standard used in this study was based on the judgment of three clinicians. While this represents an improvement over similar reports that employed even fewer clinician judgments (13–15), the low number of experts has obvious limitations. Also, while the 75% concordance rate among the clinicians allowed their judgments to be used as a criterion standard, the 25% discordance raises questions about the sources and implications of this disagreement. Last, our expert judges noted the limitations of basing their judgments on one event (interview with the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool—Clinical Research Version), given only in audio format; thus, their judgments were made under somewhat artificial constraints.

Despite these limitations, several points are worth noting. First, a standardized measure of abilities relevant to capacity was adapted for use in persons with Alzheimer’s disease and yielded reliable measurements of decisional impairment. Interscorer and interexaminer reliability were high; it is not surprising that the latter was lower. The instrument is a semistructured interview. While most interviews lasted 15–25 minutes, some of the Alzheimer’s disease subjects took longer because the interviewer had to carefully probe the subjects’ responses and proceed at the pace best tolerated by each. This inevitably introduced variability in performance between interviews and will affect routine use of the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool—Clinical Research Version in this population.

Second, a three-psychiatrist expert judgment criterion proved to be a reliable provisional standard for criterion validation, with good overall agreement (75%) and adequate kappa scores (ranging from 0.49 to 0.76). Cutoff points on the competence assessment tool with reasonable sensitivities and specificities were ascertainable through this method. However, the specific cutoff scores found in this study may be useful for decision making only in studies of similar risks and potential benefits, as well as of comparable study design complexity. It is important to remember that the goal in using the expert judgment validation was not to provide cutoff points to be used mechanically with the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool—Clinical Research Version for all contexts. Such a procedure would be meaningless in a risk-related model of competence.

Third, it seems that even relatively mild dementia can have a significant impact on Alzheimer’s disease subjects’ decision-making abilities as compared to normal comparison subjects. In this mildly to moderately impaired Alzheimer’s disease group, 62% (per expert judgment) to 84% (per normative standards) of Alzheimer’s disease subjects were rated as incapacitated on at least one decision-making ability. In contrast, the elderly comparison subjects performed the task with ease. This finding on capacity for research consent is consistent with previous findings by Marson et al. (10) on capacity for providing treatment consent among similarly impaired Alzheimer’s disease subjects.

Fourth, there was a discrepancy between cutoff scores based on normative values versus those based on expert judgment. Since an expert judgment criterion may carry more ethical weight than an arbitrary cutoff based on normative values, this is an important finding. The experts tended to be more “lenient,” which was not predictable a priori and speaks to the need to empirically examine the validity of proposed methods for categorizing impaired persons as capable or incapable. In this climate of increasing calls for formal capacity assessments (1, 2), the validity of a proposed assessment method must be carefully evaluated.

Finally, it cannot be determined from this study whether the “leniency” of the expert judges reflected a bias in favor of research, a bias in favor of the strengths of the subjects, or some other bias, if at all. There may be a complex relationship between the performance level of the subject, the context of the research scenario (the complexity of research design, the risk and potential benefits of the study, etc.), and the clinical judgments brought to bear on those factors. In the future, if competency research is to be action guiding, this complex relationship between the various components of the capacity determination process must be systematically studied.

|

|

|

Presented in part at the 13th annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, Miami, March 12–15, 2000. Received May 23, 2000; revision received Nov. 7, 2000; accepted Dec. 12, 2000. From the Department of Psychiatry and Division of Medical Humanities, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry; and the Geriatric Neurology and Psychiatry Clinic, Monroe Community Hospital, Rochester, N.Y. Address reprint requests to Dr. Kim, Department of Psychiatry, University of Rochester, 300 Crittenden Blvd., Rochester, NY 14642; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by NIMH grant MH-18911 and the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry Eisai-Pfizer Alzheimer’s Disease Research Fellowship. The authors thank Colleen McCallum, M.S.W., for assistance in coordination of the study; Pierre Tariot, M.D., Anton Porsteinsson, M.D., Frederick Marshall, M.D., and Charles Duffy, M.D., for patient recruitment; Christopher Cox, Ph.D., for statistical consultation; Yeates Conwell, M.D., for suggestions; and Paul S. Appelbaum, M.D., for training in use of the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool—Clinical Research Version.

1. Bonnie R: Research with cognitively impaired subjects: unfinished business in the regulation of human research. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:105–111Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. National Bioethics Advisory Commission: Research Involving Persons With Mental Disorders That May Affect Decisionmaking Capacity. Rockville, Md, NBAC, 1998Google Scholar

3. American Psychiatric Association: Guidelines for assessing the decision-making capacities of potential research subjects with cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1649–1650Google Scholar

4. Charney DS, Innis B, Nestler EJ: New requirements for manuscripts submitted to Biological Psychiatry: informed consent and protection of subjects. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 46:1007–1008Google Scholar

5. High DM: Advancing research with Alzheimer disease subjects: investigators’ perceptions and ethical issues. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1993; 7:165–178Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS, Mulvey EP, Fletcher K: The MacArthur Treatment Competence Study, II: measures of abilities related to competence to consent to treatment. Law Hum Behav 1995; 19:127–148Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS, Hill-Fotouhi C: The MacCAT-T: a clinical tool to assess patients’ capacities to make treatment decisions. Psychiatr Serv 1997; 48:1415–1419Google Scholar

8. Appelbaum PS, Grisso T, Frank E, O’Donnell S, Kupfer DJ: Competence of depressed patients for consent to research. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1380–1384Google Scholar

9. Carpenter WT Jr, Gold J, Lahti A, Queern C, Conley R, Bartko J, Kovnick J, Appelbaum PS: Decisional capacity for informed consent in schizophrenia research. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:533–538Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Marson DC, Ingram KK, Cody HA, Harrell LE: Assessing the competency of patients with Alzheimer’s disease under different legal standards: a prototype instrument. Arch Neurol 1995; 52:949–954Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Wirshing DA, Wirshing WC, Marder SR, Liberman RP, Mintz J: Informed consent: assessment of comprehension. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1508–1511Google Scholar

12. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS: Assessing Competence to Consent to Treatment: A Guide for Physicians and Other Health Professionals. New York, Oxford University Press, 1998Google Scholar

13. Schmand B, Gouwenberg B, Smit JH, Jonker C: Assessment of mental competency in community-dwelling elderly. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1999; 13:80–87Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Fazel S, Hope T, Jacoby R: Assessment of competence to complete advance directives: validation of a patient centered approach. Br Med J 1999; 318:493–497Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Janofsky JS, McCarthy RJ, Folstein MF: The Hopkins Competency Assessment Test: a brief method for evaluating patients’ capacity to give informed consent. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1992; 43:132–136Abstract, Google Scholar

16. Etchells E, Darzins P, Silberfeld M, Singer PA, McKenny J, Naglie G, Katz M, Guyatt GH, Molloy DW, Strang D: Assessment of patient capacity to consent to treatment. J Gen Intern Med 1999; 14:27–34Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM: Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of the Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 1984; 34:939–944Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Appelbaum PS, Grisso T: The MacArthur Treatment Competence Study, I: mental illness and competence to consent to treatment. Law Hum Behav 1995; 19:105–126Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Fleiss J: Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions, 2nd ed. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1981Google Scholar

20. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS: Comparison of standards for assessing patients’ capacities to make treatment decisions. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1033–1037Google Scholar