Insomnia, Self-Medication, and Relapse to Alcoholism

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study was an investigation of the frequencies of insomnia and its self-medication with alcohol in a group of alcoholic patients, as well as the relationship of these variables to alcoholic relapse. METHOD: The subjects were 172 men and women receiving treatment for alcohol dependence. They completed a sleep questionnaire, measures of alcohol problem severity and depression severity, and polysomnography after at least 2 weeks of abstinence. RESULTS: On the basis of eight items from the Sleep Disorders Questionnaire, 61% of the subjects were classified as having symptomatic insomnia during the 6 months before treatment entry. Compared to patients without insomnia, patients with insomnia were more likely to report frequent alcohol use for sleep (55% versus 28%), had significantly worse polysomnographic measures of sleep continuity, and had more severe alcohol dependence and depression. Among 74 alcoholics who were followed a mean of 5 months after treatment, 60% with baseline insomnia versus 30% without baseline insomnia relapsed to any use of alcohol, a significant difference. Insomnia remained a robust predictor of relapse after application of logistic regression analysis to control for other variables. A history of self-medicating insomnia with alcohol did not significantly predict subsequent relapse. CONCLUSIONS: The majority of alcoholic patients entering treatment reported insomnia symptoms. Given the potential link between insomnia and relapse, routine questions about sleep in clinical and research settings are warranted.

Although it is commonly accepted that individuals with alcohol dependence sleep poorly (1–3), few studies have investigated the rate of insomnia in alcoholic patients. Baekeland et al. (4) reported that 36% of 294 alcoholic outpatients had high scores for sleep disturbance as measured by a clinic physician. Similarly, Feuerlein (5) reported that 37% of 184 inpatients and outpatients with alcoholism had “sleep disturbance” as determined by a semistandardized interview. Caetano et al. (6) investigated insomnia as a withdrawal symptom and found a 42% rate among 445 people referred to educational programs for driving under the influence of alcohol and a 67% rate among 748 men admitted to detoxification and residential treatment centers. These insomnia rates (36% to 67%) are higher than those found in the general population (17% to 30%) (7). Nevertheless, comparisons of these studies are difficult, because different insomnia measures and time frames were used and because the study groups may have differed in demographic characteristics, drinking severity, presence of alcohol withdrawal, and diagnostic comorbidity.

To our knowledge, the occurrence of insomnia and its self-medication with alcohol has not been investigated simultaneously in alcoholic groups (4–6). Nevertheless, other studies provide useful frequency estimates of self-medication. Skoloda et al. (8) reported that 62% of treated alcoholics believed that alcohol helped them sleep. Likewise, Mamdani et al. (9) found that 60% of 92 male inpatients with alcoholism reported hypnotic use of alcohol. These self-medication rates are greater than rates reported for the general population (6% to 13%) and for people with initial insomnia (15% to 28%) (10–12). Perhaps the highest rate of self-medication was reported for a group of 155 older women (85 or more years old) with symptomatic insomnia, of whom 70% used alcohol for sleep (13).

Given that insomnia during early recovery has been linked to relapse (8, 14–16), the frequency and correlates of insomnia in alcoholics are important areas of investigation. In the present study of patients with alcoholism, we investigated 1) the frequency and clinical correlates of insomnia, 2) the frequency of drinking to self-medicate insomnia, and 3) the relationships of insomnia and self-medication to subsequent relapse. We reasoned that patients with alcoholism who reported insomnia would be more likely to self-medicate insomnia with alcohol and, therefore, more likely to relapse than patients without insomnia. We also hypothesized that self-reported insomnia would be associated with female gender, older age, more severe alcohol dependence, more severe depression, and worse sleep continuity as measured by polysomnography.

Method

Subjects

Subjects with DSM-III-R diagnoses of alcohol dependence were recruited to participate in a study examining the effects of aging and alcoholism on sleep (17). Because six patients were missing data on critical sleep items, as will be described, the group size for data analyses was reduced from 178 to 172. The recruitment sites and a description of these subjects have been reported previously (14). Briefly, about 50% of the subjects were recruited from the inpatient alcohol unit at the Ann Arbor Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and 50% were recruited from inpatient and outpatient alcohol treatment programs of the University of Michigan Medical Center. The use of multiple treatment programs for recruitment ensured a demographically heterogeneous study group (14).

The subjects were screened for medical and psychiatric conditions that might influence sleep. We excluded individuals with current major depression or a history of psychosis or bipolar disorder or borderline personality disorder, with heart disease, severe liver disease, seizure disorder (except seizures related to alcohol withdrawal), degenerative central nervous system disease, or cerebrovascular disease; or with a recent loss of consciousness due to head trauma. Psychiatric diagnoses were determined by using a revised edition of the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) (18). A past history of major depression, current dysthymic disorder, or an anxiety disorder was not a cause for exclusion. Patients with antisocial personality disorder were not excluded unless the investigators judged that the disorder would interfere with the study procedures. Other causes for exclusion included use of medications that affect sleep: psychotropic medications, centrally acting antihypertensives, oral corticosteroids, and theophylline. Patients who met the DSM-III-R criteria for abuse of or dependence on substances other than alcohol were not excluded, as long as they were substance free (except for nicotine) for the 2 weeks before the sleep study. Subjects were excluded if they worked night shifts or intentionally stayed awake during usual bedtime hours.

The protocol for this study was approved by the University of Michigan Medical Center institutional review board. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained.

Procedures

The baseline evaluation consisted of a complete medical history, physical examination, psychiatric interview, substance use history, psychosocial history, and sleep evaluation. Of the original 172 subjects, 74 (43.0%) completed follow-up interviews either by telephone or in person, a mean of 5 months after baseline. Research assistants, who were blind to the results of the subjects’ sleep evaluations, conducted the follow-up interviews to assess whether the subjects had relapsed. For the purpose of this study, relapse was defined as any alcohol use during the interim period.

At baseline, the subjects underwent one or more nights of nocturnal polysomnography at the University of Michigan sleep laboratory a minimum of 2 weeks after admission to a treatment center and their last drink. Some subjects were studied from their hospital rooms, which were connected by telemetry to the sleep laboratory. The mean time between the patient’s last drink and polysomnography was 31.5 days (SD=15.5). Only data from the first night of sleep monitoring were used for this report, because not all subjects completed more than one night of study.

Sleep was monitored by using standard polysomnographic techniques, including an electroencephalogram (EEG: C3/A2) and electro-oculogram. The data were digitized by using a bedside portable computer and were then transmitted to sleep-analyzing computers in the control room. The EEG channel was digitally filtered to yield a nominal band pass of 0.1 to 30 Hz. The data were displayed at a rate of 10 mm/second as a virtual polygraph page on a high-resolution monitor and were stored to a hard disk at a rate of 250 samples/second.

The records were masked to remove identifying information so that the scorers would be blind to diagnostic and treatment status, and they were then manually scored by using 1-minute epochs (19). Sleep latency was defined in this study as the time from the start of recording to the onset of stage 2, 3, or 4 or REM sleep with a duration of at least 10 minutes and with no more than 2 minutes of stage 1 or 1 minute of stage 1 plus 1 minute of wakefulness. The duration of slow wave sleep was calculated by adding the times spent in stage 3 and stage 4 sleep. Corrected REM sleep latency was defined as the time between sleep onset and the first REM period (at least 3 minutes of REM sleep within 30 minutes of each other) minus intermittent wakefulness during that interval.

Instruments and Measures

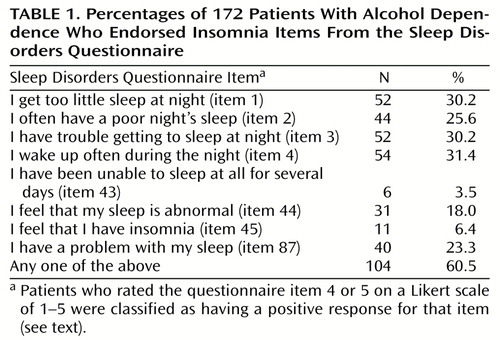

The Sleep Disorders Questionnaire is a 175-item, self-administered instrument that was given at baseline to measure subjective sleep quality and complaints related to nocturnal breathing disturbance, leg movements, daytime sleepiness, and psychiatric distress (20). The subjects responded to individual questions about the past 6 months (such as “I have trouble getting to sleep at night”) by choosing among five Likert-scaled response categories: 1=never or strongly disagree, 2=rarely or disagree, 3=sometimes or not sure, 4=usually or agree, and 5=always or agree strongly. We classified subjects at baseline with insomnia if they scored a 4 or 5 on any one of the eight items from the Sleep Disorders Questionnaire that we judged a priori to reflect complaints of insomnia (Table 1). Another Sleep Disorders Questionnaire question, “I often use alcohol in order to get to sleep” (item 105), was used as the measure of self-medication. If a subject scored 4 or 5 on this question, then that subject met the threshold for self-medication.

The revised DIS (18) yielded a lifetime DSM-III-R symptom count for alcohol dependence (maximum=9), which was used as a measure of diagnostic severity. The Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (MAST) provided another index of lifetime severity of drinking problems (21). The Carroll Rating Scale for Depression (22) was used to assess self-reported depressive symptoms at baseline. Higher scores indicate greater severity of depression. At follow-up, drinking was determined by self-report, a method that is generally considered valid when conditions of trust and lack of negative consequences for relapse are established (23).

Data Analyses

The rates of insomnia and drinking to self-medicate insomnia were expressed as percentages of the total study group (N=172). The patients were then divided into two subgroups according to the presence or absence of insomnia, and differences between groups were tested by chi-square analysis, for dichotomous variables, and by t tests, for continuous variables. Nonnormally distributed continuous variables were transformed to approximate a normal distribution before testing. Many variables can be generated and analyzed from polysomnography, and this can lead to type I errors when groups are compared on all such measures. To minimize the risk of type I error, the tests were restricted to variables for which there were a priori hypotheses. Three measures of sleep continuity (sleep latency, wake time after sleep onset, and sleep efficiency) were hypothesized to be worse for patients with than without self-reported insomnia. The percentages of total sleep time spent in slow wave sleep, percentages of time spent in REM sleep, and corrected REM sleep latencies in the patients with and without insomnia were compared, because these variables have been associated with alcoholic relapse in other studies (14, 24–26). We hypothesized that patients with insomnia would have a lower percentage of slow wave sleep, a higher percentage of REM sleep, and a shorter corrected REM sleep latency. All tests were two-tailed, and alpha was set at 0.05.

For analyses of the follow-up group (N=74), we used univariate analyses to compare the followed and not-followed groups on baseline variables. Any differences between the two groups were entered as covariates in logistic regression analyses predicting relapse in the follow-up group. Collinearity was evaluated by using the tolerance statistic, which ranges from 0 to 1, with lower values indicating more collinearity (27). For example, a tolerance value of 0.25 indicates that 75% of a variable’s variance can be explained by other entered variables. Tolerance values higher than 0.6 indicated acceptable levels of collinearity.

Results

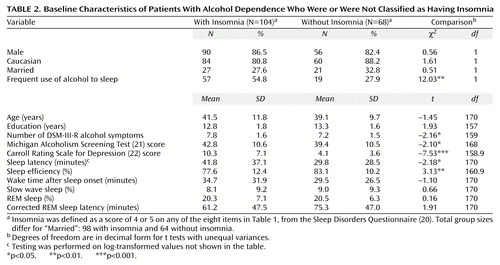

The percentage of subjects with a positive response to each of the eight insomnia-related Sleep Disorders Questionnaire items appears in Table 1. Of the 172 alcoholic patients, 60.5% had a positive response on at least one of the eight items and were therefore classified as having insomnia. The patients classified as having insomnia had significantly longer sleep latency times and lower sleep efficiency values on polysomnography than patients without insomnia (Table 2). The insomnia group had higher values for wake time after sleep onset than the group without insomnia, although the difference was not significant.

The patients with insomnia scored significantly higher on both measures of alcohol severity—DSM-III-R symptom count and MAST score—and on the Carroll Rating Scale for Depression than did the patients without insomnia (Table 2). No significant differences were found for demographic variables. The patients with insomnia were more likely to report using alcohol often for sleep than were the patients without insomnia (Table 2). Altogether, 76 (44.2%) of the 172 patients responded that they often used alcohol to get to sleep. We found no significant differences between groups in percentage of REM sleep, percentage of slow wave sleep, or corrected REM sleep latencies, although the patients with insomnia tended to have shorter corrected REM sleep latency than the patients without insomnia (Table 2).

Of the 74 patients who were followed after treatment, 36 (48.6%) relapsed. Because the follow-up rate was only 43.0%, we compared the followed (N=74) and nonfollowed (N=98) patients on baseline characteristics. We found no significant differences between these two groups in terms of insomnia rate, age, gender, race, marital status, education, number of DSM-III-R alcohol dependence symptoms, MAST score, sleep efficiency, sleep latency, percentage of slow wave sleep, percentage of REM sleep, corrected REM sleep latency, or recruitment site. The followed patients had longer wake times after sleep onset than the nonfollowed patients (mean=38.1 minutes, SD=34.7, versus mean=28.5 minutes, SD=25.0) (t=–2.01, df=126.7, p=0.05) and also had higher depression scores (mean=9.0, SD=7.8, versus mean=6.9, SD=5.5) (t=–1.96, df=125.8, p=0.052). Therefore, these two variables were included in the regression analyses (to be described).

Within the subjects who were followed up, the patients with baseline insomnia were more likely to relapse (59.6%, 28 of 47) than those without baseline insomnia (29.6%, eight of 27) (χ2=6.16, df=1, p=0.02). The patients with and without insomnia had nearly identical follow-up durations (mean=142.9 days, SD=54.6, versus mean=142.4 days, SD=57.1) (t=–0.04, df=72, p=0.97), so they had similar risk periods for relapse. To determine the effect of insomnia on relapse after controlling for severity of alcohol dependence (MAST score and DSM-III-R alcohol dependence symptom count), depression severity (Carroll scale score), and wake time after sleep onset, we used a logistic regression analysis in which all variables were forced to stay in the model. This analysis included 70 subjects because data on some variables were missing for four patients. We found that baseline insomnia was the only significant predictor of relapse (Wald χ2=4.90, df=1, p=0.03). The collinearity was acceptable, with tolerance values ranging from 0.64 to 0.92.

The followed patients who used alcohol to self-medicate insomnia had a higher relapse rate (59.5%, 22 of 37) than the patients who did not self-medicate (37.8%, 14 of 37), a difference that approached significance (χ2=3.46, df=1, p=0.07). After we controlled for drinking severity, depression severity, and wake time after sleep onset using another forced-entry logistic regression analysis, the self-medication variable remained nonsignificant (Wald χ2=2.70, df=1, p=0.10). Again, the collinearity statistics were acceptable, with tolerance values ranging from 0.74 to 0.94.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the occurrence of symptomatic insomnia and drinking to self-medicate insomnia have not been simultaneously studied in alcoholic patients. According to a measure derived from the Sleep Disorders Questionnaire, over 60% of our study group reported high levels of insomnia symptoms during the 6 months before treatment. Also, nearly 45% of the alcoholic patients reported using alcohol often in order to get to sleep during the 6 months before treatment. The patients with insomnia were about twice as likely to report using alcohol to sleep as patients without insomnia were (55% versus 28%). Similar rates of insomnia (4–6) and its self-medication with alcohol (8, 9) have been found in other studies of alcoholic patients in treatment, even though the frequency rates across studies vary according to subject characteristics, time frame, and measures of insomnia. A similar rate of self-medicating insomnia with alcohol among patients with schizophrenia (56%) (28) suggests that some of our findings may generalize to other patient populations as well.

That alcohol-dependent patients use alcohol to self-medicate insomnia is both understandable and maladaptive. On the one hand, if insomnia is a withdrawal symptom, either acute or protracted (6, 29), then relief drinking is a likely strategy, especially given that alcohol has a reinforcing effect in individuals with insomnia (30). On the other hand, there is general scientific consensus that both acute and chronic alcohol use disrupt sleep patterns (1–3, 31, 32). Therefore, self-medication of insomnia with alcohol, even if reinforcing, may paradoxically worsen insomnia. Consequently, a vicious circle may develop in which alcohol initially makes it easier to fall asleep, but as tolerance to this sedative effect develops, the sleep-disruptive effects of alcohol become more apparent if not more severe (31). Some patients may persist with self-medication despite worsening insomnia, because their drinking behavior is ingrained and reinforcing, and they feel desperate for sleep.

The levels of severity of both alcohol dependence and depression were significantly associated with insomnia. Because we excluded patients with current major depression, depressive symptoms in this study were most likely related to alcohol, dysthymia, or social stressors. We did not find higher rates of insomnia in women than in men or as a function of increasing age, a result contrary to findings in some studies of the general population (33, 34) and primary care practices (35). Age and gender differences for insomnia may disappear among patients seeking treatment for alcohol dependence. Although alcoholism severity and depression severity were significantly associated with insomnia, we did not measure anxiety symptoms despite evidence from recent studies (36, 37) that supports a significant relationship between anxiety and sleep disturbance in alcoholic patients. Therefore, further studies are needed before we can make more than tentative conclusions about the correlates of insomnia among alcoholic patients.

As in other studies (8, 14–16), baseline insomnia predicted relapse to alcoholism. Baseline insomnia remained a predictor of relapse even after we controlled for severity of alcohol dependence and depressive symptoms. Contrary to our hypothesis, patients with a history of self-medicating insomnia with alcohol were not significantly more likely to relapse than nonmedicating patients.

Of the eight insomnia items, “I feel that I have insomnia” and “I have been unable to sleep at all for several days” were least sensitive, with only 6% and 4% of the subjects endorsing these respective items (Table 1). Other insomnia items were endorsed by 18% to 32% of the subjects. This finding suggests that patients who report symptoms of insomnia do not necessarily think of themselves as having insomnia. Asking patients if they have insomnia may be analogous to asking them if they are alcoholic; patients may avoid these labels because of denial, stigma, definitions of these terms that exclude themselves, and/or fear of treatment implications. Not being able to sleep at all for several days is uncharacteristic of alcohol dependence except for extreme cases of alcohol withdrawal, such as those involving delirium tremens, which occurs in only about 5% of alcohol-dependent patients (38). This may explain the insensitivity of that question. Future studies should address the optimal screening questions for insomnia among alcoholic patients.

Several methodological issues may limit the interpretation of results. First, we studied alcoholic patients who underwent polysomnography for research purposes. It is possible that alcoholics in treatment who have sleep complaints are likely to volunteer for sleep studies, thus skewing our frequency rates for insomnia and its self-medication with alcohol. However, our rate of insomnia was comparable to the rates in other studies (4–6) and provides further evidence of the frequency of these phenomena. Nevertheless, many patients may have entered the study because of their sleep problems, which could limit the generalizability of these results.

Second, our eight-item measure of insomnia was derived from a standardized and validated sleep questionnaire (20), but full psychometric testing of the abbreviated questionnaire was beyond the scope of this study. For example, we did not calculate the sensitivity and specificity of the eight-item insomnia measure, because we did not conduct standardized clinical interviews for insomnia, and polysomnography by itself is not a gold standard for the evaluation of insomnia (39, 40). Nevertheless, in addition to face validity, the insomnia measure was associated with drinking and depression severity, with polysomnographic measures of sleep fragmentation, and with relapse, providing evidence of concurrent, external, and predictive validity, respectively.

Third, only 43% of the patients were followed over time. The low follow-up rate reflects the fact that longitudinal outcomes were added as a secondary area of interest after the beginning of our primary investigations on the effects of alcoholism and aging on sleep abnormalities (17). It is true that the followed and not-followed patients did not differ on any baseline variables except depression and wake time after sleep onset, and when these two variables were entered into the logistic regression analysis, insomnia remained a robust predictor of relapse. Nevertheless, the low follow-up rate remains a limitation, because patients lost to follow-up have potentially higher relapse rates than followed patients. Fourth, sleep measures were recorded on only one night, which did not allow subjects to adjust to the “first night effect” of sleeping under novel conditions. Fifth, relapse status was determined solely by self-report without biochemical or other corroboration, such as by a friend or family member. Still, whatever self-report bias occurred was expected to be similar across comparison groups.

In summary, symptoms of chronic insomnia and the use of alcohol to aid sleep were prevalent in alcoholic patients. Insomnia was significantly associated with severity of alcohol dependence, depressive symptoms, and polysomnographic measures of poor sleep continuity, and it was predictive of drinking during the follow-up period. These results suggest that alcoholic patients at risk for relapse are easily identifiable by routine questions about sleep. The potential for improving drinking outcomes by treating insomnia in alcoholic patients is now being investigated (41–43).

|

|

Presented in part at the 22nd annual meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism, Santa Barbara, Calif., June 26 to July 1, 1999. Received April 13, 2000; revision received July 20, 2000; accepted Oct. 4, 2000. From the Departments of Psychiatry and Neurology and the Alcohol Research Center, University of Michigan Medical School. Dr. Aldrich died in July 2000; he was a Professor of Neurology and founding director of the University of Michigan Sleep Disorders Laboratory. Address reprint requests to Dr. Brower, University of Michigan Alcohol Research Center, Suite 2A, 400 East Eisenhower Parkway, Ann Arbor, MI 48108; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by grants AA-07378, AA-00304, and AA-07477 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The authors thank Dr. Brenda Gillespie for statistical consultation.

1. Benca RM, Obermeyer WH, Thisted RA, Gillin JC: Sleep and psychiatric disorders: a meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:651–668Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism: Alcohol and sleep. Alcohol Alert 1998; 41:1–4Google Scholar

3. Vitiello MV: Sleep, alcohol, and alcohol abuse. Addiction Biology 1997; 2:151–158Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Baekeland F, Lundwall L, Shanahan TJ, Kissin B: Clinical correlates of reported sleep disturbance in alcoholics. Q J Stud Alcohol 1974; 35:1230–1241Google Scholar

5. Feuerlein W: The acute alcohol withdrawal syndrome: findings and problems. Br J Addict 1974; 69:141–148Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Caetano R, Clark CL, Greenfield TK: Prevalence, trends, and incidence of alcohol withdrawal symptoms: analysis of general population and clinical samples. Alcohol Health Res World 1998; 22:73–79Medline, Google Scholar

7. Mellinger GD, Balter MB, Uhlenhuth EH: Insomnia and its treatment: prevalence and correlates. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985; 42:225–232Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Skoloda TE, Alterman AI, Gottheil E: Sleep quality reported by drinking and non-drinking alcoholics, in Addiction Research and Treatment: Converging Trends. Edited by Gottheil EL. Elmsford, NY, Pergamon Press, 1979, pp 102–112Google Scholar

9. Mamdani MB, Hollyfield RL, Ravi SD, Dorus W, Borge GF: Sleep complaints and recidivism in alcoholics reporting use of alcohol as a hypnotic (abstract). Sleep Res 1988; 17:293Google Scholar

10. Johnson EO, Roehrs T, Roth T, Breslau N: Epidemiology of alcohol and medication as aids to sleep in early adulthood. Sleep 1998; 21:178–186Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Ancoli-Israel S, Roth T: Characteristics of insomnia in the United States: results of the 1991 National Sleep Foundation Survey, I. Sleep 1999; 22(suppl 2):S347–S353Google Scholar

12. Walsh J, Ustun TB: Prevalence and health consequences of insomnia. Sleep 1999; 22(suppl 3):S427–S436, S446–S450Google Scholar

13. Johnson JE: Insomnia, alcohol, and over-the-counter drug use in old-old urban women. J Community Health Nurs 1997; 14:181–188Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Brower KJ, Aldrich MS, Hall JM: Polysomnographic and subjective sleep predictors of alcoholic relapse. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1998; 22:1864–1871Google Scholar

15. Drummond SPA, Gillin JC, Smith TL, DeModena A: The sleep of abstinent pure primary alcoholic patients: natural course and relationship to relapse. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1998; 22:1796–1802Google Scholar

16. Foster JH, Peters TJ: Impaired sleep in alcohol misusers and dependent alcoholics and the impact upon outcome. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1999; 23:1044–1051Google Scholar

17. Aldrich MS, Brower KJ, Hall JM: Sleep-disordered breathing in alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1999; 23:134–140Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Ratcliff KS: The National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: its history, characteristics, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 38:381–389Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Rechtschaffen A, Kales AA: A Manual of Standardized Terminology, Techniques and Scoring System for Sleep Stages of Human Subjects: NIH Publication 204. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1968Google Scholar

20. Douglass AB, Bornstein R, Nino-Murcia G, Keenan S, Miles L, Zarcone V Jr, Guilleminault C, Dement WC: The Sleep Disorders Questionnaire, I: creation and multivariate structure of SDQ. Sleep 1994; 17:160–167Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Selzer M: The Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test: the quest for a new diagnostic instrument. Am J Psychiatry 1971; 127:1653–1658Google Scholar

22. Carroll BJ, Feinberg M, Smouse PE, Rawson SG, Greden JF: The Carroll Rating Scale for Depression, I: development, reliability and validation. Br J Psychiatry 1981; 138:194–200Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Babor TF, Stephens RS, Marlatt GA: Verbal report methods in clinical research on alcoholism: response bias and its minimization. J Stud Alcohol 1987; 48:410–424Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Gillin JC, Smith TL, Irwin M, Butters N, Demodena A, Schuckit M: Increased pressure for rapid eye movement sleep at time of hospital admission predicts relapse in nondepressed patients with primary alcoholism at 3-month follow-up. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:189–197Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Allen RP, Wagman AMI, Funderburk FR: Slow wave sleep changes: alcohol tolerance and treatment implications. Adv Exp Med Biol 1977; 85A:629–640Google Scholar

26. Clark CP, Gillin JC, Golshan S, Demodena A, Smith TL, Danowski S, Irwin M, Schuckit M: Increased REM sleep density at admission predicts relapse by three months in primary alcoholics with a lifetime diagnosis of secondary depression. Biol Psychiatry 1998; 43:601–607Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. SPSS Base 10.0 Applications Guide. Chicago, SPSS, 1999, p 221Google Scholar

28. Noordsy DL, Drake RE, Teague GB, Osher FC, Hurlbut SC, Beaudett MS, Paskus TS: Subjective experiences related to alcohol use among schizophrenics. J Nerv Ment Dis 1991; 179:410–414Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Satel SL, Kosten TR, Schuckit MA, Fischman MW: Should protracted withdrawal from drugs be included in DSM-IV? Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:695–704Google Scholar

30. Roehrs T, Papineau K, Rosenthal L, Roth T: Ethanol as a hypnotic in insomniacs: self administration and effects on sleep and mood. Neuropsychopharmacology 1999; 20:279–286Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Aldrich M: Effects of alcohol on sleep, in Alcohol Problems and Aging: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Research Monograph 33: NIH Publication 98-4163. Edited by Gomberg ESL, Hegedus AM, Zucker RA. Bethesda, Md, NIAAA, 1998, pp 281–300Google Scholar

32. Castaneda R, Sussman N, Levy R, O’Malley M, Westreich L: A review of the effects of moderate alcohol intake on psychiatric and sleep disorders. Rec Dev Alcohol 1998; 14:197–226Medline, Google Scholar

33. Ford DE, Kamerow DB: Epidemiologic study of sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders. JAMA 1989; 262:1479–1484Google Scholar

34. Costa e Silva JA, Chase M, Sartorius N, Roth T: An overview of insomnias and related disorders—recognition, epidemiology, and rational management. Sleep 1996; 19:412–416Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Hohagen F, Rink K, Kappler C, Schramm E, Riemann D, Weyerer S, Berger M: Prevalence and treatment of insomnia in general practice. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1993; 242:329–336Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Mackenzie A, Funderburk FR, Allen RP: Sleep, anxiety, and depression in abstinent and drinking alcoholics. Subst Use Misuse 1999; 34:347–361Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Robinson EAR, Cardinez MMV, Brower KJ: Anxiety symptoms predict initial insomnia among alcoholic outpatients (abstract). Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2000; 24(suppl 5):144AGoogle Scholar

38. Hersh D, Kranzler HR, Meyer RE: Persistent delirium following cessation of heavy alcohol consumption: diagnostic and treatment implications. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:846–851Link, Google Scholar

39. Reite M, Buysse D, Reynolds C, Mendelson W: The use of polysomnography in the evaluation of insomnia. Sleep 1995; 18:58–70Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Chervin RD: Use of clinical tools and tests in sleep medicine, in Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine, 3rd ed. Edited by Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 2000, pp 535–546Google Scholar

41. Karam-Hage M, Brower KJ: Gabapentin treatment for insomnia associated with alcohol dependence (letter). Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:151Link, Google Scholar

42. Longo LP, Johnson B: Treatment of insomnia in substance abusing patients. Psychiatr Annals 1998; 28:154–159Crossref, Google Scholar

43. Greeff AP, Conradie WS: Use of progressive relaxation training for chronic alcoholics with insomnia. Psychol Rep 1998; 82:407–412Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar