Occurrence of Thrombocytopenia in Psychiatric Patients Taking Valproate

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Few studies, with conflicting results, have examined the occurrence of thrombocytopenia with valproate administration. This study assessed whether the platelet-lowering effects of valproate are increased among elderly psychiatric patients. METHOD: The charts of 39 psychiatric inpatients taking valproate were reviewed. Information on hematologic function and on doses and serum levels of valproate at sequential intervals over a 12-month period was abstracted. Data for subjects age <60 years (nonelderly subjects) and those age ≥60 years (elderly subjects) were compared. RESULTS: More than half (53.8%) of the elderly patients but only 13.0% of the nonelderly patients had at least one episode of thrombocytopenia. This difference corresponded to a significantly greater lowering of platelet counts among elderly patients than among nonelderly patients. CONCLUSIONS: The high rate of thrombocytopenia in our study suggests the need for routine monitoring of platelet counts among patients taking valproate, particularly among elderly patients.

Valproate or divalproex sodium has been used with increasing frequency for the treatment of many psychiatric conditions (1), including those in elderly patients (2). There have been wide-ranging reports of thrombocytopenia and other forms of platelet dysfunction as side effects of valproate therapy, but, as the manufacturer states, the exact incidence is not known (3). No reports have specifically described an increased occurrence of thrombocytopenia associated with valproate use in elderly patients.

Thrombocytopenia has been reported in 6%–33% of adult patients with epilepsy taking valproate, but a lowering of platelet count was seen in almost all patients and appeared to be dose related (4, 5). Thrombocytopenia associated with valproate therapy has been reported to resolve without interruption of valproate treatment (6) and has also been reported to endure over time or to have an erratic course (7). Reports on the use of valproate with psychiatric patients have described a drop in platelet count without thrombocytopenia or with a minimal incidence of thrombocytopenia (8, 9) and without any associated adverse clinical events related to these findings (10). The perceived novelty and underrecognition of the platelet-lowering effects of valproate is illustrated by case reports of thrombocytopenia associated with valproate in psychiatric populations (11).

On the basis of clinical observations of adult psychiatric patients, we hypothesized that there is a notable occurrence of thrombocytopenia in patients taking valproate. During data collection, we developed a further hypothesis that the platelet-lowering effects of valproate are increased in elderly patients. If these hypotheses are true, more careful monitoring than is currently suggested in the psychiatric literature is warranted, especially in the treatment of elderly patients, who are at increased risk for medical comorbidity, polypharmacy, and traumatic falls.

Method

We conducted a retrospective review of the charts of 39 patients who were started on a regimen of divalproex sodium while hospitalized at a state psychiatric hospital. The research was approved by the hospital research committee. Patients were used as their own comparison subjects in a pretreatment-posttreatment research design. Three patients were excluded because baseline values were not available. Data on baseline hematologic function, including platelet counts, were sought and then serially reviewed within the first month of treatment with valproate, between the first and third months, the third and sixth months, the sixth and ninth months, and after 9 consecutive months of treatment. Some patients were followed for as long as 12 months. The incidence of thrombocytopenia (platelet count <100,000/mm3) (12), as well as the mean overall drop in platelet count, was recorded. Particular attention was paid to the dose and serum level of divalproex sodium coinciding with measurement of the hematologic parameters. Psychiatric diagnoses and medications, as well as general medical conditions and use of medications known to cause thrombocytopenia, were noted.

The subjects were grouped on the basis of age (the nonelderly group was <60 years old, and the elderly group was ≥60 years old), and comparisons were made between the groups. General descriptive statistics, Fisher’s exact tests, Spearman correlations (rs), and t tests were used to analyze the data. Repeated measures ANOVA was used to assess the effect of age on platelet level across time. Mean scores were substituted for missing platelet levels at 1, 3, and 6 months. Long-term effects (at 9 months and at >9 months) were assessed in smaller study groups from which patients that had reduced or discontinued valproate were excluded.

Results

Of the 36 patients with baseline data, 13, 10 of whom were male, were over age 60 (the elderly group). The mean age of the elderly group was 69.38 years (SD=4.75, range=63–81). Sixteen of the 23 patients in the nonelderly group were male. The mean age of the nonelderly group was 43.04 years (SD=10.06, range=22–59). At baseline, the two groups did not differ in gender or ethnicity. There were more elderly than nonelderly patients with organic disorders such as dementia, which would be expected (p<0.04, Fisher’s exact test, two-tailed). There were more nonelderly than elderly patients with “other” psychiatric diagnoses, which were generally comorbid conditions such as mental retardation and dyskinesias (p<0.04, Fisher’s exact test, two-tailed).

Older age did not correlate with a lower baseline platelet level (rs=0.02, p=0.46). Ten of the 36 patients (27.8%) had at least one recorded episode of thrombocytopenia (a total of 15 recorded platelet counts<100,000/mm3). Eight of the 10 patients were male. Three patients each had two episodes, and one patient had three episodes. Seven of the 13 elderly patients (53.8%) had at least one recorded episode of thrombocytopenia (a total of 12 recorded platelet counts <100,000/mm3). Six of the seven were male. In the nonelderly group, thrombocytopenia occurred in three (13.0%) of 23 patients. Two of the three patients were male. Thrombocytopenia was significantly more likely to occur in the elderly group (p<0.02, Fisher’s exact test, two-tailed).

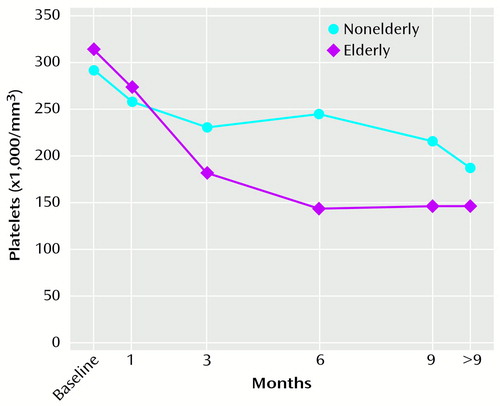

The mean platelet levels for the elderly and nonelderly groups are shown in Figure 1. The two groups’ mean platelet levels were not significantly different at baseline (t=–0.68, df=14.69, p=0.51). A repeated measures ANOVA testing the interaction of group and time (F=3.10, df=5, 80, p<0.02) indicated that platelet levels were lower in the elderly group than in the nonelderly group beginning at 3 months and over the rest of the 1-year study period. Post hoc testing with the Dunn multiple-comparison test showed significant differences between groups at 3 months and 9 months (p<0.05). However, there was substantial variability in platelet levels of the elderly patients at 6 months, and the difference between groups did not reach significance.

The daily dose of valproate in all subjects ranged from 250 to 4500 mg. The mean daily dose of valproate was slightly higher in the elderly group than in the nonelderly group, but the difference was not significant. The mean daily dose after the first month of treatment ranged from 1900 to 2225 mg in the elderly group and from 1400 to 1850 mg in the nonelderly group. Valproate serum levels in all subjects ranged between 16–161 μg/ml. These levels were not significantly different between the elderly and nonelderly groups and generally ranged between 70–90 μg/ml after the first month of treatment.

During the study period, the dose of valproate was reduced in two elderly patients and one nonelderly patient in response to low platelet levels. Eleven patients, five of whom were elderly, were discontinued from valproate treatment for various reasons, such as noncompliance and inadequate treatment response, that were generally not associated with clinical complications or adverse reactions. However, a 68-year-old woman was noted to have had significant thrombocytopenia (platelet level=21,000/mm3) when she developed central nervous system toxicity that resulted in discontinuation of valproate. An elderly man who was also prescribed warfarin developed spontaneous subcutaneous facial bleeding.

Discussion

The study results show that thrombocytopenia occurs in psychiatric patients who are taking valproate, particularly in elderly patients. The results support our hypothesis of significant differences in the occurrence of thrombocytopenia and of an overall drop in platelet count in elderly versus nonelderly patients. The differences noted in diagnoses between the groups were not unexpected and did not seem to be related to the platelet levels. Increased adverse drug reactions in elderly patients have been linked to several mechanisms, including pharmacodynamic as well as pharmacokinetic alterations, use of multiple drug therapy, increased severity of illness, and a high incidence of comorbid medical conditions in elderly patients (13). Prior accounts have suggested that valproate may cause hematologic toxicity by mechanisms that vary with aging (14) and that the therapeutic dose and serum level of valproate may be lower in elderly than in nonelderly patients (15). In our study, elderly patients received a higher mean dose, compared to the nonelderly patients, and had similar serum levels.

Reports of severe thrombocytopenia and hematologic toxicity with valproate treatment are generally thought to be rare, and most authors feel that clinical problems are unlikely (4, 5). Because of concerns about valproate’s effects on platelet function as well as the erratic nature of adverse reactions and the difficulties detecting these problems, neurological investigators have suggested careful monitoring (9, 14). The bulk of psychiatric research involving valproate has not emphasized the importance of close monitoring, although some case reports have illustrated potential clinical implications and have recommended establishing a guideline for monitoring, adjusting, and discontinuing valproate (11). Our study provides evidence in support of regular monitoring of platelet level among patients taking valproate, particularly elderly patients.

This study was limited by its retrospective design, small number of subjects, and lack of a control group. Despite these limitations, our evidence shows that thrombocytopenia does occur in psychiatric patients taking valproate and suggests that elderly patients are more susceptible to these effects. A further concern would be whether elderly patients are more susceptible to platelet dysfunction and to effects of valproate on clotting factors and fibrinogen, which would put them at even greater risk of adverse hematologic events. Additional studies, preferably with a prospective design, are needed to clarify the incidence and occurrence of thrombocytopenia in psychiatric patients taking valproate. Specific questions should include further clarification of the association between platelet dysfunction and valproate treatment in elderly patients.

Presented in part at the ninth annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, Tucson, Ariz., Feb. 14–17, 1996; the 149th annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, New York, May 4–9, 1996; and the 48th Institute on Psychiatric Services, Chicago, Oct. 18–22, 1996. Received June 9, 1999; revisions received Feb. 16, April 24, and June 27, 2000; accepted July 17, 2000. From the Hawaii State Psychiatric Hospital, Kaneohe; and the Department of Psychiatry, John A. Burns School of Medicine, University of Hawaii, Manoa. Address reprint requests to Dr. Trannel, Gundersen Lutheran Medical Center, 1836 South Ave., La Crosse, WI 54601-5494; [email protected] (e-mail).

Figure 1. Mean Platelet Levels Over Time in Elderly and Nonelderly Psychiatric Patients Taking Valproatea

aNo significant difference between groups at baseline. Significant interaction of group and time beginning at 3 months (repeated measures ANOVA, F=3.10, df=5, 80, p<0.02).

1. McElroy SL, Keck PE Jr, Pope HG Jr, Hudson JI: Valproate in psychiatric disorders: literature review and clinical guidelines. J Clin Psychiatry 1989; 50(suppl 3):23–29Google Scholar

2. Risinger RC, Risby ED, Risch SC: Safety and efficacy of divalproex sodium in elderly bipolar patients (letter). J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55:215Medline, Google Scholar

3. Eliopoulos H: Thrombocytopenia Coincident With Depakote Therapy. Abbott Park, Ill, Abbott Pharmaceutical Products Division, Professional Information and Product Safety, 1993Google Scholar

4. Neophytides AN, Nutt JG, Lodish JR: Thrombocytopenia associated with sodium valproate treatment. Ann Neurol 1979; 5:389–390Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Covanis A, Gupta AK, Jeavons PM: Sodium valproate: monotherapy and polytherapy. Epilepsia 1982; 23:693–720Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Eastham RD, Jancar J: Sodium valproate and platelet counts (letter). Br Med J 1980; 280:186Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. May RB, Sunder TR: Hematologic manifestations of long-term valproate therapy. Epilepsia 1993; 34:1098–1101Google Scholar

8. Calabrese JR, Markovitz PJ, Kimmel SE, Wagner SC: Spectrum of efficacy of valproate in 78 rapid-cycling bipolar patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1992; 12(suppl 1):53S–56SGoogle Scholar

9. Tohen M, Castillo J, Baldessarini RJ, Zarate C Jr, Kando JC: Blood dyscrasias with carbamazepine and valproate: a pharmacoepidemiological study of 2,228 patients at risk. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:413–418Link, Google Scholar

10. Bowden CL, Brugger AM, Swann AC, Calabrese JR, Janicak PG, Petty F, Dilsaver SC, Davis JM, Rush AJ, Small JG (The Depakote Mania Study Group): Efficacy of divalproex vs lithium and placebo in the treatment of mania. JAMA 1994; 271:918–924Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Kaufman KR, Gerner R: Dose-dependent valproic acid thrombocytopenia in bipolar disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry 1998; 10:35–37Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Wyngaarden JB, Smith LH Jr, Bennett JC: Cecil Textbook of Medicine, 19th ed. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1992Google Scholar

13. Nolan L, O’Malley K: Prescribing for the elderly, part I: sensitivity of the elderly to adverse drug reactions. J Am Geriatr Soc 1988; 36:142–149Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Gidal B, Spencer N, Maly M, Pitterle M, Williams E, Collins M, Jones J: Valproate-mediated disturbances of hemostasis: relationship to dose and plasma concentration. Neurology 1994; 44:1418–1422Google Scholar

15. Puryear LJ, Kunik ME, Workman R Jr: Tolerability of divalproex sodium in elderly psychiatric patients with mixed diagnoses. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1995; 8:234–237Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar