Protective Factors Against Suicidal Acts in Major Depression: Reasons for Living

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Over 30,000 people a year commit suicide in the United States. Prior attempted suicide and hopelessness are the most powerful clinical predictors of future completed suicide. The authors hypothesized that “reasons for living” might protect or restrain patients with major depression from making a suicide attempt.METHOD: Inpatients with DSM-III-R major depression were assessed for depression, general psychopathology, suicide history, reasons for living, and hopelessness. Of the 84 patients, 45 had attempted suicide and 39 had not.RESULTS: The depressed patients who had not attempted suicide expressed more feelings of responsibility toward family, more fear of social disapproval, more moral objections to suicide, greater survival and coping skills, and a greater fear of suicide than the depressed patients who had attempted suicide. Scores for hopelessness, subjective depression, and suicidal ideation were significantly higher for the suicide attempters. Reasons for living correlated inversely with the combined score on these measures, considered an indicator of “clinical suicidality.” Neither objective severity of depression nor quantity of recent life events differed between the two groups.CONCLUSIONS: During a depressive episode, the subjective perception of stressful life events may be more germane to suicidal expression than the objective quantity of such events. A more optimistic perceptual set, despite equivalent objective severity of depression, may modify hopelessness and may protect against suicidal behavior during periods of risk, such as major depression. Assessment of reasons for living should be included in the evaluation of suicidal patients.

Over 30,000 people a year commit suicide in the United States. Suicide is the eighth leading cause of death and among the top three causes of death in 18–24-year-olds. A variety of factors have been identified in the literature as being risk factors for suicidal behavior among persons with major depression. Prior attempted suicide and hopelessness are the most powerful clinical predictors of future completed suicide (1–7). Although substantial efforts have been made to understand what risk factors contribute to suicide and suicidal behavior, less attention has been paid to clinical features that may protect against the emergence of suicidal behavior during major depression.

We have previously hypothesized a stress-diathesis model for the expression of both suicidal behavior and completed suicide (1). This model is derived from the observation that although a considerable proportion of the population experience significant stressors and major depressive episodes, only a minority of those individuals will act on suicidal thoughts (2). Consequently, we have defined a trigger domain that is related to stressors, and therefore is state dependent, and a diathesis or threshold domain, which is more trait dependent. Neither domain, in and of itself, determines suicidality. However, when risk factors across domains are combined, the likelihood of suicidal acts is greater, either because internal restraint against suicidal acts diminishes or because excess stress increases the suicidal impulse/idea (1).

Differences in the risk of suicidal behavior among various communities, generations, and religious groups suggest that in addition to biological, social, and environmental determinants of suicidal acts, there may also be significant modulation by religious or cultural variables (8). A seldom-posed but important question is not why depressed patients want to commit suicide, but why they want to live. Patients who struggle with suicidal urges or feelings describe reasons for living that help them resist these suicidal feelings. Some of these protective social or cultural factors are reflected in a scale designed to assess reasons for living—the Reasons for Living Inventory (9).

The Reasons for Living Inventory is a self-report instrument that measures beliefs that may contribute to the inhibition of suicidal behavior (9). It is composed of six factors: survival and coping beliefs, responsibility to family, child-related concerns, fear of suicide, fear of social disapproval, and moral objections to suicide. These factors are composites of true or false responses to statements such as “Life is all we have and is better than nothing,” “I am afraid of the unknown,” “My religious beliefs forbid it,” “It would not be fair to leave the children for others to take care of,” and “I believe I have control over my life and destiny,” which have apparent influences from culture, religion, and sociopolitical attitudes. The scale has been validated, and its reliability has been documented (9).

In this study we examined correlates of a history of suicide attempts in patients with major depression. Patients with or without such a history were compared. The Reasons for Living Inventory was used to identify factors that may protect against or modulate the expression of suicidal behavior during depressive episodes. Severity of mood disorder and life events was assessed. We hypothesized that more reasons for living would be associated with fewer and less intense suicidal acts or less suicidal ideation during a depressive episode. We also hypothesized that reasons for living would correlate inversely with hopelessness, suicidal ideation, and subjective depression—“clinical suicidality”—and therefore would be an important clinical modulator of risk for suicidal acts.

Method

Subjects were recruited from patients admitted to two urban university psychiatric hospitals (Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, Pittsburgh, and New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York). Subjects aged between 18 and 80 years who met the DSM-III-R criteria for current major depressive episode during the intake clinical assessment and were free of severe, unstable medical and neurologic disorders were approached regarding participation in clinical and biologic research studies on suicidal behavior and mood disorders. The nonparticipants did not differ significantly from the research participants on key demographic and clinical variables, such as age, sex, race, severity of depression on admission, or number of previous depressive episodes. The nonparticipants were more likely to have been substance abusers (data not presented). All research participants signed informed consent statements approved by the relevant university institutional review boards.

The subjects were clinically assessed for depression, and the diagnosis of a current major depressive episode was based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Patient Version (10). The severity of the major depressive episode was measured objectively with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (11) and subjectively with the Beck Depression Inventory (12), and hopelessness was assessed with the Hopelessness Scale (13). General psychopathology was assessed by using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (14). In addition to administering the Reasons for Living Inventory, we assessed the quantity and severity of life events by using the St. Paul Ramsay Life Experience Scale and Recent Life Changes Questionnaire (15). We compiled a comprehensive lifetime history of lifetime suicidal acts (16) and administered the Scale for Suicide Ideation (17) to assess current ideation, the Suicide Intent Scale (18) to assess intent at the most lethal and most recent suicide attempt, and the Medical Lethality Scale (19) for measurement of medical injury resulting from suicidal acts.

Results

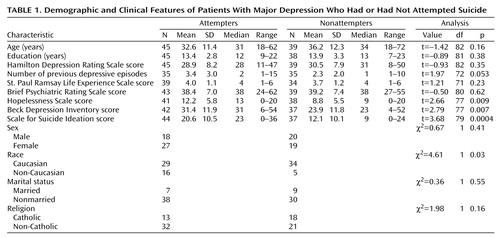

Age, sex, educational experience, and religious persuasion failed to distinguish between suicide attempters and nonattempters (Table 1). Of note, the depressed non-Caucasians were significantly less likely to have attempted suicide than were the depressed Caucasians. Number, duration, and objective severity of depressive episodes also failed to distinguish the suicide attempters from nonattempters. However, the difference in number of episodes of major depression was nearly significant (p=0.053). Moreover, the suicide attempters reported significantly greater subjective depression, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation than the nonattempters (Table 1). No difference in the distribution of unipolar versus bipolar depression could be detected, as there were only three patients with bipolar disorder in the study group (Fisher’s two-tailed p=0.59).

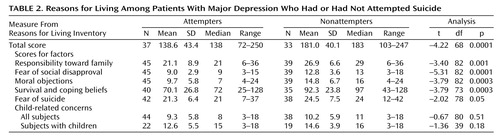

The depressed patients who had not attempted suicide scored significantly higher on total reasons for living (Table 2). Analysis of the categories of reasons for living revealed that the depressed patients who had not attempted suicide had greater survival and coping beliefs, greater fear of social disapproval, and greater moral objections to suicide than the suicide attempters. Fear of suicide also was statistically different between the attempters and nonattempters, but it was not as powerful a discriminating factor. When the analysis of child-related concerns was limited to the subjects with offspring, the nonattempters had nonsignificantly more child-related concerns than the suicide attempters (Table 2). By classifying the suicide attempts as having high or low lethality, we also examined whether any of the individual reasons for living predicted the lethality of suicide attempts. Moral objection to suicide was the only reason for living that was significantly stronger in the subjects with low-lethality suicide attempts (mean=13.1, SD=7.0, N=10) than in those with high-lethality attempts (mean=8.7, SD=5.2, N=35) (t=–2.00, p=0.05).

In a Pearson correlation analysis, the total score for reasons for living was significantly inversely correlated with the scores for hopelessness (r=–0.58, N=67, p<0.0001), suicidal ideation (r=–0.48, N=68, p<0.0001), and subjective depression (Beck Depression Inventory) (r=–0.42, N=66, p<0.0005). We used canonical correlation analysis to examine the relationship between reasons for living and the sum of the scores for hopelessness, subjective depression, and suicidal ideation—a measure of “clinical suicidality.” Clinical suicidality was highly significantly inversely correlated with reasons for living (canonical correlation=–0.64, likelihood ratio=0.59, df=3, 59, N=62, p<0.0001).

Discussion

Our findings regarding patients with major depressive disorder are consistent with results in a previous study of borderline personality disorder (9), in which more reasons for living in depressed patients protected against acting on suicidal thoughts at vulnerable times. In our study, a higher total score for reasons for living was associated with less hopelessness, and therefore, both variables may modulate the threshold for acting on suicidal thoughts. Given higher hopelessness scores in the suicide attempters, the observation that life events did not differ significantly between the suicide attempters and nonattempters suggests that the subjective perception of stressful life events may be more germane to suicidal expression than objective quantitative measures of such events.

Chiles and colleagues (20) reported disparate findings. Among the Chinese patients they studied, depression, rather than hopelessness, was related to suicidal intent. They postulated that the connection between hopelessness and intent may not have been so relevant for their Chinese subjects because of differing moral or cultural experiences and beliefs, whereby the enduring attitude is that one has little control over adverse events. Reasons for living, like hopelessness, may reflect a cultural or environmental component in the suicide threshold and may contribute to variation in suicide rates among different cultures. Hopelessness is difficult to categorize as either environmental or biological, as an acute clinical trigger, or as a chronic threshold-influencing factor (7). Clinically, the degree of hopelessness can vary considerably in an individual. Yet, even when acute hopelessness remits, for example upon resolution of major depression, significantly higher levels of hopelessness remain in patients with past suicide attempts (2). Low scores for reasons for living may also be considered to behave in a similar fashion. Although it measures a different construct, the total score for reasons for living correlates inversely with the construct of “clinical suicidality”—hopelessness, subjective depression, and suicidal ideation—and may hypothetically vary within an individual, depending on whether or not external triggers are present. The suicide attempters had a somewhat, but nonsignificantly, higher number of depressive episodes. It is possible that repeated exposure to depression, rather than the duration of depression, may be an additional risk factor for suicidal acts in patients who experience suicidality when depressed. This possibility underscores the importance of early and adequate antidepressant treatment and prophylactic treatment against further depressive episodes (21). The patients in this study are being followed prospectively so that we can examine whether reasons for living are truly protective and whether other clinical factors, such as clinical suicidality, are risk factors.

Whereas religious persuasion did not differentiate the patients with and without suicide attempts, the scores for moral objections to suicide differed strongly. Moreover, greater moral objection to suicide also protected against higher-lethality suicidal acts among the suicide attempters. Thus, reasons for living may be a more sensitive indicator of enduring moral/religious beliefs than is “religion of origin” per se. For example, the recent alarming rise in suicide rates in Ireland parallels a reported decline in religious practice rather than any change in the religion of origin there (22).

As a way of understanding whether race, culture, or religion has an effect, some authors have explored the differences in rates of suicide among various ethnic groups. For instance, acculturated Hispanics are at greater risk for suicidal thoughts and behavior than are less acculturated Hispanics, a difference that has been attributed to the gap between rising expectations and limited socioeconomic opportunities (23), and Mexican Americans in general have a lower rate of suicide than Anglo Americans (24). The rate of suicide in black adolescents is rising, although the reasons for this are unclear (25). The rate of suicide among blacks remains well below the rate for whites. It is possible that the more interactive role of the church in black communities and the view of “suicide as a white thing” by blacks (26) may protect against suicide. It may be that “live religion” supports reasons for living, which in turn provide protection against suicide in times of stress.

Caution is required when generalizing from our results, as the study group was small and confined to patients with major depression. The nonparticipants had more substance abuse, and so specific studies of substance abusers need to be conducted to identify specific risk factors for suicidal acts in this high-risk group. It would also be important to replicate our findings in larger and more diverse clinical groups, including patients with bipolar disorder and patients with schizophrenia.

The total score for reasons for living was inversely correlated with the sum of the scores for hopelessness, subjective depression, and suicidal ideation—a combination that may be termed “clinical suicidality”—which makes intuitive clinical sense. Perhaps treatment strategies that reduce clinical suicidality, or that increase awareness of reasons for living, may be complementary, and they should be explored. Reasons for living should be included in the clinical assessment of suicidal patients, and treatment strategies that support reasons for living and instill hope during times of stress, such as a major depressive episode, need to be developed.

|

|

Received Sept. 29, 1998; revision received Oct. 13, 1999; accepted Jan. 27, 2000. Presented in part at the 150th annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, San Diego, May 17–22, 1997. From the Mental Health Clinical Research Center for the Study of Suicidal Behavior, New York State Psychiatric Institute and Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University, New York; and the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Address reprint requests to Dr. Malone, Mental Health Clinical Research Center for the Study of Suicidal Behavior, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1051 Riverside Dr., New York, NY 10032; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grants MH-46745 and MH-48514 and by the Georgia and Glenn H. Greenberg Philanthropic Fund.

1. Mann JJ, Waternaux C, Haas GL, Malone KM: Toward a clinical model of suicidal behavior in psychiatric patients. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:181–189Abstract, Google Scholar

2. Malone KM, Haas GL, Sweeney JA, Mann JJ: Major depression and the risk of attempted suicide. J Affect Disord 1995; 34:173–185Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Bulik CM, Carpenter LL, Kupfer DJ, Frank E: Features associated with suicide attempts in recurrent major depression. J Affect Disord 1990; 18:29–37Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Roy A: Features associated with suicide attempts in depression: a partial replication. J Affect Disord 1993; 27:35–38Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Rich CL, Warstadt GM, Nemiroff RA, Fowler RC, Young D: Suicide, stressors, and the life cycle. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:524–527; correction, 148:960Link, Google Scholar

6. Soloff PH, Lis JA, Kelly T, Cornelius J, Ulrich R: Risk factors for suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1316–1323Google Scholar

7. Beck AT, Steer RA, Kovacs M, Garrison B: Hopelessness and eventual suicide: a 10-year prospective study of patients hospitalized with suicidal ideation. Am J Psychiatry 1985; 142:559–563Link, Google Scholar

8. Diekstra RFW, Garnefski N: On the nature, magnitude, and causality of suicidal behaviors: an international perspective. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1995; 5:36–57Google Scholar

9. Linehan MM, Goodstein JL, Nielsen SL, Chiles JA: Reasons for staying alive when you are thinking of killing yourself: the Reasons for Living Inventory. J Consult Clin Psychol 1983; 51:276–286Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Patient Version (SCID-P). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1990 Google Scholar

11. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J: An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961; 4:561–571Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Beck AT, Weissman A, Lester D, Trexler L: The measurement of pessimism: the Hopelessness Scale. J Consult Clin Psychol 1974; 42:861–865Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep 1962; 10:799–812Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Rahe RH: Epidemiological studies of life change and illness. Int J Psychiatry Med 1975; 6:133–146Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Malone KM, Szanto K, Corbitt EM, Mann JJ: Clinical assessment versus research methods in the assessment of suicidal behavior. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1601–1607Google Scholar

17. Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A: Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for Suicide Ideation. J Consult Clin Psychol 1979; 47:343–352Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Beck AT, Weissman A, Lester D, Trexler L: Classification of suicidal behaviors, II: dimensions of suicidal intent. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976; 33:835–837Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Beck AT, Beck R, Kovacs M: Classification of suicidal behaviors, I: quantifying intent and medical lethality. Am J Psychiatry 1975; 132:285–287Link, Google Scholar

20. Chiles JA, Strosahl KD, Ping ZY, Michael MC, Hall K, Jemelka R, Senn B, Reto C: Depression, hopelessness, and suicidal behavior in Chinese and American psychiatric patients. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146:339–344Link, Google Scholar

21. Oquendo MA, Malone KM, Ellis SP, Sackeim HA, Mann JJ: Inadequacy of antidepressant treatment of patients with major depression who are at risk for suicidal behavior. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:190–194Abstract, Google Scholar

22. Department of Health and Children, National Task Force on Suicide: Report of the National Task Force on Suicide (abstract). Dublin, Stationery Office, 1998, pp 5–84Google Scholar

23. Sorenson SB, Golding JM: Suicide ideation and attempts in Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites: demographic and psychiatric disorder issues. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1988; 18:205–219Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Hoppe SK, Martin HW: Patterns of suicide among Mexican Americans and Anglos, 1960–1980. Soc Psychiatry 1986; 21:83–88Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Shaffer D, Gould M, Hicks RC: Worsening suicide rate in black teenagers. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1810–1812Google Scholar

26. Early KE, Akers RL: “It’s a white thing”: an exploration of beliefs about suicide in the African-American community. Deviant Behavior: An Interdisciplinary J 1993; 14:277–296Crossref, Google Scholar