A Placebo-Controlled Study of Fluoxetine Versus Imipramine in the Acute Treatment of Atypical Depression

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The atypical subtype of depression appears to be both well validated and common. Although monoamine oxidase inhibitors are effective in treating atypical depression, their side effects and prescription-associated dietary restrictions reduce their suitability as a first-line treatment. The objective of this study was to estimate the efficacy of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) fluoxetine in the treatment of major depression with atypical features. METHOD: One hundred fifty-four subjects with DSM-IV major depression who met the Columbia criteria for atypical depression were randomly assigned to receive fluoxetine, imipramine, or placebo for a 10-week clinical trial. Imipramine was included because its known efficacy for treatment of atypical depression helped to calibrate the appropriateness of the study group. RESULTS: In both intention-to-treat and completer groups, the effectiveness of both fluoxetine and imipramine was significantly better than that of placebo. The two medications did not differ from each other in effectiveness. Significantly more patients dropped out of treatment with imipramine than with fluoxetine. Before treatment, patients on average rated themselves as very impaired on psychological dimensions of general health and moderately impaired on physical dimensions, compared with population norms. The self-ratings of patients who responded to treatment essentially normalized on these measures. CONCLUSIONS: Despite earlier data that SSRIs might be the treatment of choice, fluoxetine appeared to be no better than imipramine in the treatment of atypical depression, although fluoxetine was better tolerated than imipramine.

Both treatment outcome and biological marker studies suggest that major depressive episodes are heterogeneous. Apart from bipolar depression, the best validated clinical subtypes are psychotic, melancholic, and atypical (1). Atypical features have been included in DSM-IV as a possible specifier for each of the principal depressive diagnoses. The DSM-IV criteria for atypical features include mood reactivity in addition to two of the following symptoms: overeating, oversleeping, “leaden paralysis” or severe lack of physical energy, and pathologic sensitivity to interpersonal rejection. Treatment studies at Columbia University played a pivotal role in validating this subtype by demonstrating an advantage for monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) over tricyclics in patients with features characteristic of this subtype (2–6). Additional support for the distinctiveness of this subtype comes from studies of neuroendocrine response (7), sleep architecture (8), and family history (9). (See references 9 and 10 for reviews of this evidence.) Latent class analyses of depressive symptoms reported by subjects in twin (11) and epidemiologic samples (12) support the atypical subtype as a categorically distinct group. Like the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study (13), these studies show that atypical depression exists in the community at appreciable rates. Further, they identified a distinct pattern among other illness variables and increased concordance in monozygotic compared with dizygotic twins, suggesting a genetic diathesis for the subtype.

Atypical depression appears to be common among outpatients, although rates vary with the criteria applied. The ECA study found atypical depression in 15.7% of subjects with major depression using truncated criteria assessing only two of four atypical symptoms (13). This strategy necessarily assured an assessment at the lower bound of the true prevalence. Five studies have estimated the prevalence in clinical populations (7, 14–17). In 1,000 consecutive outpatients, 36% of the 175 patients with major depression met Columbia criteria for atypical depression, and 46% had reversed vegetative symptoms (14). In a series of 114 consecutive outpatients with depressive disorders, Asnis et al. (7) found a 29% prevalence, defining atypical depression as present if at least one of the four associated symptoms was present. Using the Columbia atypical depression scale, Robertson et al. (15) found that 28% of the unipolar patients and 30% of the bipolar patients they assessed met the criteria for atypical depression. In a Canadian study assessing only vegetative symptoms in major depression, 11.3% of patients had only reversed symptoms over a lifetime and another 5.8% had fluctuating symptoms (16). Nierenberg et al. (17) found a 42% rate among 392 outpatients with major depression who met the Columbia criteria for atypical depression. Most studies probably underestimate the true prevalence because the majority antedate DSM-IV and did not assess rejection sensitivity, the associated symptom observed most frequently.

Atypical depression responds relatively poorly to tricyclics and robustly to MAOIs (2–6). However, the side effect profile of MAOIs and their prescription-associated dietary restrictions reduce their suitability as a first-line treatment. MAOIs are rarely used outside of tertiary care settings, mainly because of fear of hypertensive crises. Even when used, MAOIs are associated with poor adherence rates in continuation treatment (18). The reported efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in atypical depression has varied (19–22). In an open study, Reimherr et al. (19) observed a 65% response rate for fluoxetine in patients with atypical depression as defined by the Columbia criteria. One controlled trial found the MAOI moclobemide to be superior to fluoxetine in the treatment of patients with atypical depression (20). A controlled trial found no difference between fluoxetine and phenelzine, although the small sample size precluded finding a difference in the absence of a large effect size (21). Another study with limited power due to a total sample size of only 28 subjects found no difference between fluoxetine and imipramine (22). The ease of prescription and favorable side effect profile of the SSRIs would make them a potentially attractive treatment for atypical depression if placebo-controlled studies established their utility.

The principal purpose of the study reported here was to assess the efficacy of fluoxetine compared to both placebo and imipramine in patients with atypical depression. Secondary objectives included examining the effect of atypical major depression on general health measures, documenting any changes in general health measures with treatment, and exploring any differences between using one or two associated symptoms to define atypical depression.

METHOD

This 10-week, double-blind study used a randomized parallel-group design. Patients were treated at a depression research clinic in an urban university setting by using a protocol approved by the institutional review board.

Subjects

Subjects were men and women, age 18 to 65 years, who met DSM-IV criteria for a major depressive episode for at least 1 month and also met the Columbia criteria for atypical depression (9). Unlike DSM-IV, which requires two associated symptoms together with mood reactivity for a diagnosis of atypical depression, the Columbia criteria require only one associated symptom among the following four: overeating, oversleeping, severe anergy, and pathological sensitivity to interpersonal rejection. The requirement for only one symptom is based on treatment outcome studies showing that the presence of one associated symptom appears sufficient to observe the advantage of MAOIs over tricyclics (3, 4) and evidence indicating that all associated symptoms were equivalent in predicting MAOI advantage (23). In addition, biologic, course-of-illness, and family study data indicate that patients with a single associated symptom more closely resemble those with more associated features than those with none (9).

The exclusions criteria were 1) significant suicidal risk, 2) pregnancy, lactation, or unwillingness to use effective birth control in women, 3) unstable and serious physical illness, 4) a history of seizures, 5) psychosis or organic mental syndrome, 6) substance use disorders active within 6 months, except for nicotine dependence, 7) history of mania, 8) antisocial personality disorder, 9) history of nonresponse to an adequate trial of fluoxetine (defined as 40 mg/day for at least 6 weeks) or imipramine (defined as greater than 150 mg/day for 2 consecutive weeks and 4 weeks total treatment), 10) history of nonresponse to any other SSRI, and 11) laboratory evidence of hypothyroidism.

Procedures

After subjects received a complete description of the study, they provided written informed consent. All patients had a physical examination and laboratory studies and then underwent a 1-week, single-blind placebo washout. Subjects who did not experience significant improvement, defined as a Clinical Global Impression (CGI) (24) improvement rating of “very much improved” or “much improved,” were randomly assigned to receive fluoxetine, imipramine, or placebo.

All patients received identical capsules: fluoxetine or fluoxetine placebo in the morning and imipramine or imipramine placebo at bedtime. The fluoxetine dose was 20 mg/day for the first 4 weeks, 40 mg/day for week 5, and 60 mg/day for the remaining weeks. The imipramine dose was 50 mg/day for the first week, increasing by 50 mg/day each week, until 300 mg/day was reached. Doses were raised on these occasions unless a patient was either significantly improved or reported distressing side effects. The maximum dose attained was then continued for the remainder of the study. Compliance was monitored by counts of returned pills at patients’ weekly visits to the research clinic.

Ratings

Efficacy measures rated weekly included the CGI (24), the Patient Global Improvement (25), and the 28-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (26). Other efficacy measures were the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (27), the Atypical Depression Diagnostic Scale (9), and the SCL-90 (24). Categorical response was determined from the CGI improvement score. Subjects rated “very much improved” or “much improved” at the end of treatment were considered responders; all others were considered nonresponders.

Adverse event data were collected by open-ended query at each study visit and were coded by using standard nomenclature. Calculations of rates of adverse events included events that occurred at any point in the study.

Data Analysis and Statistics

The intention-to-treat group included all subjects randomly assigned to one of the three study groups; the last observation was carried forward as an endpoint score. A minimal adequate treatment group was defined a priori to include subjects who completed at least 6 weeks of treatment and received at least 20 mg/day of fluoxetine, 150 mg/day of imipramine, or an equivalent number of placebo capsules. The completer group was made up of all subjects who completed all 10 weeks of study treatment.

Comparisons with respect to categorical measures were performed by using chi-square tests, corrected for continuity, or by using Fisher’s exact tests if there were cells with expected frequencies of less than five. Continuous baseline variables were compared by analysis of variance and considered significant if different at the p<0.15 level; a liberal significance level was employed to minimize type II error. Comparisons of a group mean with a population mean used a one-sample z test. Differences between treatment groups on continuous outcome measures were analyzed by analysis of covariance, with baseline score as the covariate. Group-by-baseline interactions were calculated to assess heterogeneity of slope for covariance analyses and were considered significant if B, the estimate of the maximum likelihood, was different at the p<0.05 level. Where significant heterogeneity of slope was detected, the Johnson-Neyman method was used to calculate the range of baseline scores beyond which treatments differed significantly (28, 29). Comparisons between pairs of treatments were made by t tests, in which the overall analysis of covariance showed significant differences. All statistics are reported two-tailed; standard deviations are reported throughout. Group comparisons on the Hamilton depression scale and CGI were planned a priori; analyses of other variables were adjusted for experiment-wise error by the Bonferroni correction, using the number of additional comparisons.

RESULTS

Group Description

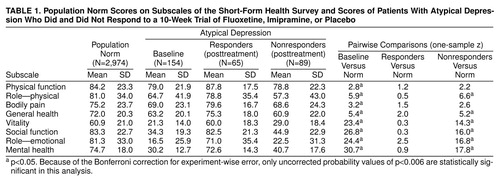

Of 203 patients who signed informed consent forms, 14 (6.9%) were rated as responders to single-blind placebo, and 35 (17.2%) either had medical exclusions after baseline studies or withdrew before being randomly assigned to a treatment group. One hundred fifty-four patients were randomly assigned to the study conditions as follows: 49 to fluoxetine, 53 to imipramine, and 52 to placebo. The randomly assigned subjects were a mean age of 41.6 years (SD=11.0); 64.3% (N=99) were female, and 85.7% (N=132) were Caucasian. The current episode of major depression of most subjects (59.1%, N=91) had a duration of 24 months or longer. Seventy-six percent (N=117) met DSM-IV criteria for atypical depression (two associated features), and the remainder (N=37) met the Columbia criteria for atypical depression (one associated feature). Randomly assigned groups did not differ on demographic variables. The groups did not differ at baseline on severity variables. Dimensions of health status at baseline, measured by the Short-Form Health Survey, and population norms (27) are presented in table 1. Subjects were significantly impaired compared with the norms on all dimensions, although impairment on emotional dimensions was most marked. Subjects were significantly less impaired on physical dimensions and more impaired on emotional dimensions compared with the Medical Outcomes Study’s depressed sample, which was drawn from non-treatment-seeking subjects in medical office settings (data are not shown [30]).

Eight of 49 patients (16.3%) randomly assigned to receive fluoxetine had previously been treated with fluoxetine, and four of those patients (50.0%) subsequently responded to the medication in this study. Nine of 53 patients (17.0%) randomly assigned to receive imipramine had previously been treated with a tricyclic antidepressant, and three (33.3%) subsequently responded in this study. The difference in rates of previous treatment between groups was nonsignificant (χ2=0.01, df=1, n.s.), as was the difference between the response rates of those who had previously received the drug they were assigned to and those who had not (fluoxetine: p=1.0, df=1, n.s.; imipramine: p=0.4, df=1, n.s., Fisher’s exact test).

Mean daily doses of active medication at endpoint were 51.4 mg/day (SD=14.6) for fluoxetine-treated patients and 204.9 mg/day (SD=90.7) for imipramine-treated patients. Placebo-treated patients received an average of 2.8 (SD=0.6) placebo fluoxetine pills in the morning and 5.5 (SD=1.3) placebo imipramine pills in the evening, equivalent to 56.0 mg/day (SD=12.0) of fluoxetine and 275.0 mg/day (SD=65.0) of imipramine, respectively.

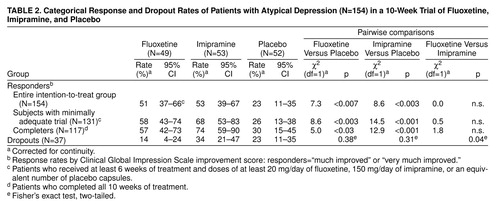

Categorical Outcomes

Response rates based on endpoint CGI improvement scores are presented in table 2. Fluoxetine and imipramine did not differ from one another in efficacy, and both were significantly more effective than placebo in the intention-to-treat, adequate treatment, and completer groups. There was a significantly higher dropout rate on imipramine compared with fluoxetine. In the analyses to follow, we will focus on the intention-to-treat group to estimate treatment effect without bias related to attrition.

Continuous Depression Outcome Measures

Continuous depression outcome measures for the intention-to-treat group are summarized in table 3. The 17-item and 28-item Hamilton depression scales, Patient Global Improvement, and SCL-90 summary and subscale scores show a consistent pattern of advantage for both drug groups over placebo, but no differences between fluoxetine and imipramine.

Significant slope heterogeneity (group-by-slope interaction terms F=3.1, df=2, 149, to F=5.5, df=2, 149, p<0.05 to p<0.01) was found for five of the nine SCL-90 subscales, as indicated in table 3. In each case, the direction of the finding was for imipramine to show a shallower slope (range=0.19 to 0.38) compared with placebo (range=0.63 to 0.92), indicating a larger imipramine-placebo difference for patients with higher baseline scores. On two of these six SCL-90 subscales, phobia and paranoia, there was also significant slope heterogeneity between fluoxetine and placebo. This finding was also in the direction of larger drug-placebo differences for subjects with more pathologic baseline scores. Using a liberal criterion of p<0.15, there were baseline differences on the SCL-90 paranoia subscale, on which most of the items appear more related to interpersonal sensitivity than to psychotic paranoia. The mean for patients who received imipramine was lower (less pathological) than the mean for patients on placebo. Together with the observed heterogeneity of slopes, this finding makes the standard comparisons of adjusted means uninformative and misleading. Unlike findings for the other subscales, fluoxetine was superior to imipramine for high baseline severity of paranoia. The benefit of the two active drugs was more pronounced for higher baseline severity, although the placebo group contained more patients with low baseline severity. This characteristic of the placebo group obscures the beneficial effect of the active drugs on the means or the adjusted means at the end of the study. The effect of the drugs with respect to this subscale becomes apparent only after taking into account the baseline imbalances between groups and the heterogeneity of the slopes.

To illustrate the range of baseline scores that determine slope heterogeneity for the SCL-90, we present the results for the SCL-90 summary score, which is representative in direction and magnitude of the effects seen with the subscales. Using the Johnson-Neyman procedure, we found that fluoxetine was significantly more effective than placebo for subjects with an SCL-90 summary score of 14 or higher, and imipramine was significantly more effective than placebo for subjects with scores of 17 or higher. These values correspond to the 23rd and 33rd percentile of baseline severity, respectively, for the entire group.

Posttreatment results from the Short-Form Health Survey for treatment responders and nonresponders and population norms for the survey are presented in table 1. This presentation permits contrasts in the level of functioning of recovered depressed patients and a normative group. Responders’ scores approached population values on all dimensions, whereas nonresponders still rated themselves significantly impaired.

Only the mental health measure of the Short-Form Health Survey (27) showed improved ratings for both medications versus placebo (F=7.9, df=2, 150, p<0.05; fluoxetine versus placebo, t=3.4, df=98, p<0.01; imipramine versus placebo, t=3.4, df=103, p<0.05; all statistics corrected by the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.) Fluoxetine was most effective for those who rated themselves most pathologic at baseline on the global mental health measure (placebo slope B=0.74, fluoxetine slope B=–0.16; t=2.7, df=103, p<0.01).

Side Effects

Side effect symptoms for which the rate among patients receiving fluoxetine exceeded the rate among those receiving placebo at the p=0.05 level included nausea (fluoxetine 33%, placebo 6%), dizziness (fluoxetine 25%, placebo 8%), and constipation (fluoxetine 18%, placebo 4%). Symptoms significantly more common among patients receiving imipramine than among those receiving placebo included dry mouth (imipramine 81%, placebo 21%), dizziness (imipramine 44%, placebo 8%), somnolence (imipramine 42%, placebo 15%), constipation (imipramine 38%, placebo 4%), and nausea (imipramine 29%, placebo 6%). Symptoms significantly more common for imipramine than for fluoxetine included dry mouth (imipramine 81%, fluoxetine 28%), somnolence (imipramine 42%, fluoxetine 24%), and dizziness (imipramine 44%, fluoxetine 25%). Symptoms more common for fluoxetine than for imipramine included cough (fluoxetine 18%, imipramine 2%) and back pain (fluoxetine 16%, imipramine 2%). Interestingly, two side effects were less common among imipramine-treated patients than among placebo-treated patients: diarrhea (imipramine 8%, placebo 26%) and pain (imipramine 4%, placebo 19%). Although these last two may be chance findings, they may be a manifestation of imipramine’s well-documented constipating effect and possibly also of its analgesic effects (31).

Definite Versus Probable Atypical Depression

We used the CGI improvement rating as defined in a preceding section to calculate response rates within each treatment group between the diagnoses of probable or definite atypical depression, i.e., the presence of one versus two or more of the four associated features, respectively (3, 4). There were no significant differences within the fluoxetine group (definite N=43, probable N=6; definite response=64%, probable response=48%) (χ2=0.9, df=1, n.s.), the imipramine group (definite N=42, probable N=11; definite response rate=53%, probable response rate=53%) (χ2=0.002, df=1, n.s.), or the placebo group (definite N=44, probable N=8; definite response=22%, probable response=27%) (p=0.7, Fisher’s exact test, two-tailed, n.s.). The possible effect of diagnosis was further explored with a two-way analysis of covariance (not shown) using definite and probable atypical depression as grouping variables and the continuous outcome measures described previously as outcome variables. No main effect of definite-versus-probable diagnosis was found for any of the outcome variables; however, the small number of probable atypical cases precludes the observation of any but large effects.

DISCUSSION

Although fluoxetine and imipramine were both effective in treating atypical depression compared with placebo, the advantage of fluoxetine over a tricyclic suggested by previous studies was not observed. The response rate of about 75% seen for an MAOI in several replications does not appear to be approximated by fluoxetine in the treatment of atypical depression (3–6). Internal calibration of the validity of this trial was provided by the response rate for imipramine, which was similar to that found in previous studies of atypical depression. This finding supports the conclusion that fluoxetine may be less effective than an MAOI for atypical depression. Unfortunately, a definitive conclusion concerning the relative efficacy of fluoxetine and an MAOI cannot be made by comparing across studies, because sampling fluctuations, rating variance, and temporal effects may alter results. However, as it appears unlikely that larger clinical trials will soon be done prospectively comparing an SSRI with an MAOI, these data may have to suffice in the meantime to assist clinicians in planning treatment for depressed patients with atypical features.

The significantly higher dropout rate for imipramine compared with fluoxetine may have affected the results in that completer analyses would be expected to be favorably biased toward imipramine as patients with lack of improvement are usually overrepresented among dropouts. There appeared to be no advantage for either of the active medications over placebo in subjects in the lowest quartile of subjective distress, as measured by the SCL-90.

A limitation of these data is that the power of this study was insufficient to detect moderate-sized but clinically meaningful differences between the active medications. For example, given the 53% response rate to imipramine in the intention-to-treat analysis, our group had a one-tailed power of only 0.61 to detect a clinically meaningful increase in response rate for fluoxetine of 20% or more. With the imipramine response rate that was observed, this study would have had an 80% chance (the conventionally desirable power) to demonstrate a between-drug difference of 25%, i.e., a fluoxetine response rate of 78% or greater.

A potential confound of our study was the inclusion of subjects who had previously not responded to either 20 mg/day of fluoxetine or 150 mg/day of imipramine or an equivalent tricyclic. If 20 mg of fluoxetine is as effective as higher doses, the study could be biased against finding fluoxetine to be more efficacious than imipramine, because fluoxetine-resistant patients are included. However, few patients randomly assigned to either active treatment condition had previously received that treatment, the rates of previous treatment for both medications were equivalent, and the response rate for those previously treated did not differ from those who were not. Thus, the idea that a selection bias accounts for the findings is not supported.

These patients, experiencing major depression with atypical features, rated themselves markedly impaired on standard measures of emotional functioning, compared both with population norms and with a depressed sample. This low rating of emotional functioning is consistent with the chronic nature of atypical depression and may be a better index of the severe impairment it often causes than cross-sectional symptom scales like the Hamilton depression scale. Patients who responded to treatment improved dramatically and were indistinguishable from a normative population sample on most subscales, suggesting that the deficits measured are rapidly and almost completely responsive to medication.

Given the substantial frequency of atypical depression indicated by epidemiologic and clinical studies, these data suggest that the efficacy of heterocyclic antidepressants other than the SSRIs should be examined in patients with atypical depression. Antidepressants like bupropion, venlafaxine, and mirtazapine have in vitro pharmacologic profiles that are to varying degrees distinct from the SSRIs and may perhaps share the efficacy of the MAOIs in this patient group (32). The only such report of which we are aware is a small naturalistic study that found that among 23 patients with atypical depression, defined by having either hyperphagia or hypersomnia, depression improved significantly after bupropion but not after fluoxetine treatment (33).

As in previous studies of unselected depressed patients, the dropout rate for imipramine was significantly greater than for fluoxetine, apparently because of adverse effects. However, imipramine was effective compared with placebo, and despite its relatively sedative profile, has not been “toxic” for patients with symptoms of oversleeping or overeating, replicating a previous study (34). The side effect profile of both medications in this population approximated that for treated depressed patients generally.

The major clinical application of these data is that fluoxetine is modestly effective for atypical depression compared with placebo and is better tolerated than imipramine. Although these characteristics make fluoxetine a reasonable first-line acute treatment for atypical depression, imipramine may be a better choice for patients with significant insomnia. Further studies would be necessary to test whether the response to fluoxetine is maintained over time as it is with phenelzine, but not with imipramine (35, 36). Although MAOI therapy may be more effective than an SSRI, its hazards and side effects make reserving it for SSRI nonresponders a more prudent clinical course. Further, the degree of functional improvement seen here among responders suggests that the superiority of MAOIs is in the probability of response and not in the degree of functional improvement among responders. In addition, previous work has shown that even when MAOI therapy is efficacious, patients often discontinue it within the first 6 months, making it less than fully satisfactory maintenance treatment for this chronic disorder (20). It is important that clinicians be aware that fluoxetine would require a washout of 5 weeks or more before treatment with MAOIs, because of the long half-life of norfluoxetine, fluoxetine’s active metabolite. Remaining norfluoxetine could interact with an MAOI to cause “serotonin syndrome,” which is potentially lethal (37).

Received May 19, 1999; revision received Sept. 2, 1999; accepted Sept. 13, 1999From the New York State Psychiatric Institute, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York. Address reprint requests to Dr. McGrath, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Unit 51, 1051 Riverside Dr., New York, NY 10032-2695; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by Eli Lilly and Company and by the Office of Mental Health of the State of New York. The authors thank Freedom From Fear for help in patient recruitment and the staff of the Depression Evaluation Service at the New York State Psychiatric Institute for their work in patient care and research assessment. Donald C. Ross, Ph.D., provided a computer program for the Johnson-Neyman analyses and assistance in interpreting the results.

|

|

|

1. Joyce PR, Paykel ES: Predictors of drug response in depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:89–99Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Liebowitz MR, Quitkin FM, Stewart JW, McGrath PJ, Harrison WM, Markowitz JS, Rabkin JG, Tricamo E, Goetz DM, Klein DF: Antidepressant specificity in atypical depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:129–137Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Quitkin FM, Stewart JW, McGrath PJ, Liebowitz MR, Harrison WM, Tricamo E, Klein DF, Rabkin JG, Markowitz JS, Wager SG: Phenelzine versus imipramine in the treatment of probable atypical depression: defining syndrome boundaries of selective MAOI responders. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:306–311Link, Google Scholar

4. Quitkin FM, McGrath PJ, Stewart JW, Harrison W, Wager SG, Nunes E, Rabkin JG, Tricamo E, Markowitz J, Klein DF: Further delineation of the syndrome of atypical depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:787–793Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Quitkin FM, McGrath PJ, Stewart JW, Harrison W, Tricamo E, Wager SG, Ocepek-Welikson K, Nunes E, Rabkin JG, Klein DF: Atypical depression, panic attacks—response to imipramine and phenelzine: a replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:935–941Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Quitkin FM, Harrison W, Stewart JW, McGrath PJ, Tricamo E, Ocepek-Welikson K, Rabkin JG, Wager SG, Nunes E, Klein DF: Response to phenelzine and imipramine in placebo nonresponders with atypical depression: a new application of the crossover design. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:319–323Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Asnis GM, McGinn LK, Sanderson WC: Atypical depression: clinical aspects and noradrenergic function. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:31–36Link, Google Scholar

8. Quitkin FM, Rabkin JG, Stewart JW, McGrath PJ, Harrison WM, Davies M, Goetz R, Puig-Antich J: Sleep of atypical depressives. J Affect Disord 1985; 8:61–67Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Stewart JW, McGrath PJ, Rabkin JG, Quitkin FM: Atypical depression: a valid clinical entity? Psychiatr Clin North Am 1993; 16:479–496Google Scholar

10. Rabkin JG, Stewart JW, Quitkin FM, McGrath PJ, Harrison WM, Klein DF: Should atypical depression be included in DSM-IV?, in DSM-IV Source Book, vol 2. Edited by Widiger TA, Frances AJ, Pincus HA, Ross R, First MB, Davis WW. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994, pp 239–260Google Scholar

11. Kendler KS, Eaves LJ, Walters EE, Neale MC, Heath AC, Kessler RC: The identification and validation of distinct depressive syndromes in a population-based sample of female twins. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:391–399Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Sullivan PF, Kessler RC, Kendler KS: Latent class analysis of lifetime depressive symptoms in the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1398–1406Google Scholar

13. Horwath E, Johnson J, Weissman MM, Hornig CD: The validity of major depression with atypical features based on a community survey. J Affect Disord 1992; 26:117–126Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Zisook S, Shuchter SR, Gallagher T, Sledge P: Atypical depression in an outpatient psychiatric population. Depression 1993; 1:26–274Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Robertson HA, Lam RW, Stewart JN, Yatham LN, Tam EM, Zis AP: Atypical depressive symptoms and clusters in unipolar and bipolar depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1996; 94:421–427Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Levitan RD, Lesage A, Parikh SV, Goering P, Kennedy SH: Reversed neurovegetative symptoms of depression: a community study of Ontario. Am J Psychiatry 1997, 154:934–940Google Scholar

17. Nierenberg AA, Alpert JE, Pava J, Rosenbaum JF, Fava M: Course and treatment of atypical depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 59(suppl 18):5–9Google Scholar

18. Agosti V, Stewart JW, Quitkin FM, Rabkin JG, McGrath PJ, Markowitz J: Factors associated with premature medication discontinuation among responders to an MAOI or tricyclic antidepressant. J Clin Psychiatry 1988; 49:196–198Medline, Google Scholar

19. Reimherr FW, Wood DR, Byerley B, Brainard J, Grosser BI: Characteristics of responders to fluoxetine. Psychopharmacol Bull 1984; 20:90–92Google Scholar

20. Lonnquist J, Sihvo S, Syvalahti E, Kiviruusu O: Moclobemide and fluoxetine in atypical depression: a double-blind trial. J Affect Disord 1994; 32:169–177Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Pande AC, Haskett RF, Greden JF: Double-blind comparison of fluoxetine and phenelzine in atypical depression. Biol Psychiatry 1991; 29:117A–118AMedline, Google Scholar

22. Stratta P, Bolino F, Cupillari M, Casacchia M: A double-blind parallel study comparing fluoxetine with imipramine in the treatment of atypical depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1991; 6:193–196Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. McGrath PJ, Stewart JW, Harrison WM, Ocepek-Welikson K, Rabkin JG, Nunes E, Wager S, Tricamo E, Quitkin FM, Klein DF: The predictive value of symptoms of atypical depression for differential drug treatment outcome. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1992; 12:197–202Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76-338. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976, pp 218–222Google Scholar

25. McGlashan T (ed): The Documentation of Clinical Psychotropic Drug Trials. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1973Google Scholar

26. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Ware JE: SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston, New England Medical Center, Health Institute, 1993Google Scholar

28. Neyman J, Johnson PO: Tests of certain linear hypotheses and their application to some educational problems. Statistical Res Memoirs 1936; 1:57–93Google Scholar

29. Potthoff RF: On the Johnson-Neyman technique and some extensions thereof. Psychometrika 1964; 29:241–256Crossref, Google Scholar

30. Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, Burnam MA, Rogers W, Daniels M, Berry S, Greenfield S, Ware J: The functioning and well-being of depressed patients: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA 1989; 262:914–919Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Mitchell MB, Lynch SA, Muir J, Shoaf SE, Smoller B, Dubner R: Effects of desipramine, amitriptyline, and fluoxetine on pain in diabetic neuropathy. N Engl J Med 1992; 326:1250–1256Google Scholar

32. Stahl SM: Basic psychopharmacology of antidepressants, part 1: antidepressants have seven distinct mechanisms of action. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59(suppl 4):5–14Google Scholar

33. Goodnick PJ, Extein IL: Bupropion and fluoxetine in depressive subtypes. Ann Clin Psychiatry 1989; 1:119–122Crossref, Google Scholar

34. McGrath PJ, Stewart JW, Quitkin FM, Ocepek-Welikson K, Klein DF: Does imipramine worsen atypical depression? J Clin Psychopharmacol 1991; 11:270–272Google Scholar

35. Stewart JW, Quitkin FM, McGrath PJ, Amsterdam J, Fava M, Fawcett J, Reimherr F, Rosenbaum J, Beasley C, Roback P: Use of pattern analysis to predict differential relapse of remitted patients with major depression during 1 year of treatment with fluoxetine or placebo. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:334–345Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Montgomery SA, Dufour H, Brion S, Gailledreau J, Laqueille X, Ferrey G, Moron P, Parant-Lucena N, Singer L, Danion JM, Beuzen JN, Pierredon MA: The prophylactic efficacy of fluoxetine in unipolar depression. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1988; 3:69–76Medline, Google Scholar

37. Lane R, Baldwin D: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-induced serotonin syndrome: a review J Clin Psychopharmacol 1997; 17:208–221Google Scholar