Three-Year Follow-Up of Women With the Sole Diagnosis of Depressive Personality Disorder: Subsequent Development of Dysthymia and Major Depression

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors sought to determine whether subjects with the sole diagnosis of depressive personality disorder are at higher risk for developing dysthymia and major depression than are healthy comparison subjects. METHOD: Eighty-five women with depressive personality disorder who had no comorbid axis I or axis II disorders and 85 age-matched healthy comparison women were initially recruited and reinterviewed 3 years later to evaluate the cumulative incidence rate of dysthymia and major depression. RESULTS: At the 3-year follow-up assessment, the women with depressive personality disorder had a significantly greater odds ratio for developing dysthymia than did the healthy comparison women. The difference in odds ratios for the development of major depression between women with and without depressive personality disorder did not reach statistical significance. CONCLUSIONS: The present study, the first to determine the subsequent development of dysthymia and major depression in subjects with the sole diagnosis of depressive personality disorder, found that subjects with depressive personality disorder had a greater risk of developing dysthymia than did healthy comparison subjects at 3-year follow-up. Findings of the current study also suggest that depressive personality disorder may mediate the effects of a family history of axis I unipolar mood disorders.

In appendix B of DSM-IV, depressive personality disorder was included as a category requiring further study. Previous research has attempted to conceptualize depressive personality disorder as an axis II counterpart of the axis I depressive spectrum disorders (1–5).

The validity of the distinction between depressive personality disorder and dysthymia has been under debate, since depressive personality disorder (characterized by a pervasive pattern of depressive cognitions and behaviors) and dysthymia (with its emphasis on somatic symptoms of depression) are both in the lesser spectrum of depressive disorders (5, 6). However, empirical studies on this distinction repeatedly have reported that their overlap is far from complete (3–5, 7).

Noting the limitations of the categorical distinction between the mood and personality disorders in classifying the continuum of depressive conditions, researchers have contended that depressive personality disorder may be best viewed as 1) a characterological variant in a spectrum of depressive disorders and 2) a possible mediator of familial risk for mood disorders (5, 6, 8, 9). One efficient way to address this issue would be a long-term follow-up of subjects with depressive personality disorder.

Previous studies on the interface between depressive personality disorder and dysthymia or major depression have been mainly cross-sectional (3, 7, 10). There have been only two follow-up studies performed to assess the diagnostic stability of depressive personality disorder and to tap clinical implications of the presence of depressive personality disorder (4, 5); the follow-up periods of these two studies were 1 year and 30 months, respectively. However, the presence of comorbid axis I and II disorders in their subjects with depressive personality disorder may hinder the generalizability of the findings.

It is surprising that, to our knowledge, there have been no prior longitudinal studies of subjects with the sole diagnosis of depressive personality disorder regarding the subsequent development of dysthymia or major depression. The current study aimed to evaluate the odds ratios for developing the axis I mood disorders of dysthymia and major depression, relative to that of healthy comparison subjects, in subjects with the sole diagnosis of depressive personality disorder. On the basis of the concept that depressive personality disorder represents a “personality core” of dysthymia and major depression, as well as supportive empirical data (1, 5, 8, 9), we hypothesized that at a 3-year follow-up evaluation, subjects with depressive personality disorder would have a greater risk for developing dysthymia and major depression than would healthy comparison subjects.

Method

Subjects and Diagnostic Procedures

Subjects were female college students, either undergraduate or graduate, age 18–35, with depressive personality disorder, as determined by the Diagnostic Interview for Depressive Personality, a reliable and valid 30-item semistructured instrument that includes DSM-IV criteria and additional items regarding the concept of depressive personality disorder (4, 11).

Exclusion criteria were 1) any current or lifetime comorbid DSM-III-R axis I disorder, as determined by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID-P) (12); 2) any comorbid DSM-III-R axis II personality disorder, as determined by the Diagnostic Interview for Personality Disorders (13); and 3) concurrent neurological or other significant medical illnesses or history of brain trauma, encephalitis, seizure, attention deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD), or learning disabilities, as evaluated by a review of the subject’s history and school reports, a physical examination, and results of laboratory testing (CBC, liver function tests, serology, urinalysis).

Calculations for the size of the study group were based on the expected cumulative incidence rate differences with an alpha level of 0.05. Since there were no previous studies on subjects with the sole diagnosis of depressive personality disorder from which to infer an effect size, the effect size of 0.20 for rate differences was presumed in our study (14). To provide an expected statistical power of 0.80 or greater for detecting differences between subjects with and without depressive personality disorder, each group should have a minimum of 60 subjects at the follow-up assessment (14). Since the yearly dropout rate in a previous study of female college students with similar demographic characteristics was 9.0% (15), we determined that for the groups of women with and without depressive personality disorder, the minimum number of subjects at baseline should be 80.

Subjects with depressive personality disorder were recruited mainly through advertisements for subjects with chronic low-grade depression and also through referrals from the school clinics and consultation services at four women’s and 11 coed universities (total number of female students: >130,000) in and around metropolitan Seoul, South Korea. Subjects were recruited from October 1995 to May 1996 until the number of women with the sole diagnosis of depressive personality disorder reached at least 80. Part of the depressive personality disorder study group (N=39) were identified from unrelated studies on personality disorders (15, 16).

Of the 258 women recruited or referred with the possible diagnosis of depressive personality disorder, 173 had their diagnosis confirmed with the Diagnostic Interview for Depressive Personality. Of these, 88 subjects with a current or lifetime axis I disorder, comorbid axis II personality disorder, or a history of brain trauma, seizure, or ADHD were removed from the study, which left 85 women for our depressive personality disorder group.

Age-matched healthy comparison women (N=85) were recruited through advertisements at the same institutions. All were carefully evaluated to rule out concurrent neurological or other significant medical illnesses. The comparison women had no current or lifetime DSM-III-R axis I or axis II disorder or depressive personality disorder, as determined by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R, Non-Patient Edition (SCID-NP) (17), the Diagnostic Interview for Personality Disorders, and the Diagnostic Interview for Depressive Personality, respectively.

At the initial assessment, the Diagnostic Interview for Depressive Personality and the Diagnostic Interview for Personality Disorders were administered by two faculty-level clinical psychologists, and one psychiatrist (I.K.L.) administered the two SCID instruments. Each interviewer was blind to ratings obtained by the other two. Interrater reliabilities for each instrument, determined by means of kappa and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) (18), were measured by using 15 randomly selected videotaped interviews. Reliability ranged from moderate to good (diagnosis of depressive personality disorder: kappa=0.65; total score on the Diagnostic Interview for Depressive Personality: ICC=0.81; personality disorder diagnoses determined from the Diagnostic Interview for Personality Disorders: kappas=0.53–0.78; SCID-P diagnoses of dysthymia and major depression: kappas=0.65 and 0.73, respectively).

The Revised Family History Questionnaire (19), a reliable semistructured instrument that assesses the presence of DSM-III-R axis I disorders in relatives, was used to assess the presence of major depression, dysthymia, bipolar disorder, or cyclothymia in 215 first-degree relatives of 70 women with depressive personality disorder and 249 first-degree relatives of 76 comparison women. These represent 74.1% and 78.7% of all living first-degree relatives 14 years or older whom the authors were given permission to contact for the women with and without depressive personality disorder, respectively.

Other assessed variables included level of depression, as measured by the Korean version of the Beck Depression Inventory (20, 21), educational level in years, marital status, and social class (22). Standardized Korean versions of the instruments were used when available (21, 23), and other Korean versions of instruments were used after extensive translation and back-translation processes to ensure reliability.

Of the 85 women with depressive personality disorder at baseline, eight had dropped out of school and three had gone abroad for study and could not be contacted at follow-up. One died in an accident, and one became mentally incompetent because of a car accident. Thus, 72 women with depressive personality disorder were reinterviewed approximately 3 years after the initial interviews (within a 1-month period). Of the initially recruited 85 comparison subjects at baseline, three had dropped out of or changed their school and seven had gone abroad for study and could not be contacted. Thus, there were 75 healthy comparison women at the 3-year follow-up assessment.

The same raters reinterviewed study subjects for the presence of any current or lifetime DSM-III-R axis I diagnosis including dysthymia and major depression, using the SCID-P (12) and SCID-NP (17). Estimates of depressive personality disorder diagnostic stability were calculated for these 147 subjects over the 3-year follow-up.

After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained.

Statistical Analysis

Group differences in demographic variables that involved continuous data (age, years of education, social class, and Beck Depression Inventory scores) were computed by using Student’s t tests. Between-group differences involving categorical data (marital status and the presence of mood disorders in first-degree relatives) were assessed by using Fisher’s exact tests.

Unconditional multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the odds ratio and 95% confidence interval (CI) for the development of dysthymia, relative to that of healthy comparison subjects, in women with depressive personality disorder after other independent variables and interactions between variables in the model were controlled for. Multivariate logistic modeling was conducted according to the model-building strategies recommended by Hosmer and Lemeshow (24).

Initially, univariate logistic regression analyses were conducted to identify all important independent variables (presence of depressive personality disorder, presence of axis I mood disorders in first-degree relatives, age, years of education, marital status, social class, and Beck Depression Inventory score) with a univariate Wald chi-square probability value of 0.25 or less. This was done in order to avoid excluding variables that might be associated, collectively with other variables, with dysthymia. The presence of depressive personality disorder (Wald χ2=7.08, df=1, p=0.008) and the presence of axis I mood disorders in first-degree relatives (Wald χ2=8.83, df=1, p=0.003), age, and two interaction terms (depressive personality disorder by family history, depressive personality disorder by age) were initially included as independent variables in the multivariate regression model for dysthymia. Age, although it did not meet the inclusion criteria, was included in this and following regression models because it is an important biological variable related to the onset of depressive disorders. Interaction terms were excluded from the final logistic regression model, since differences in the goodness-of-fit chi-square values between models with and without the interaction terms were not statistically significant. Three independent variables (the presence of depressive personality disorder, the presence of axis I mood disorders in first-degree relatives, and age) and one dependent variable (the presence of dysthymia at follow-up) constituted the final regression model (likelihood ratio test, G=15.62, df=3, p<0.002).

The same set of analyses was performed to assess the odds ratio for developing major depression, relative to that of healthy comparison women, in women with depressive personality disorder. The presence of depressive personality disorder (Wald χ2=2.38, df=1, p<0.13) and the presence of axis I mood disorders in first-degree relatives (Wald χ2=6.52, df=1, p<0.02), age, and two interaction terms (depressive personality disorder by family history, depressive personality disorder by age) were initially included as independent variables. Interaction terms were excluded from the final regression model for the same reason as they were in the dysthymia analyses. Three independent variables (the presence of depressive personality disorder, the presence of axis I mood disorders in first-degree relatives, and age) and one dependent variable (the presence of major depression at follow-up) constituted the final regression model (likelihood ratio test, G=8.07, df=3, p<0.05).

Finally, the odds ratio for developing an axis I unipolar mood disorder (either dysthymia or major depression), relative to that of healthy comparison women, in women with depressive personality disorder was assessed in the same way. The presence of depressive personality disorder (Wald χ2=8.50, df=1, p=0.004) and the presence of axis I mood disorders in first-degree relatives (Wald χ2=13.45, df=1, p=0.0003), age, and two interaction terms (depressive personality disorder by family history, depressive personality disorder by age) were initially included as independent variables. Interaction terms were excluded from the final regression model for the same reason as they were in the dysthymia and major depression analyses. Three independent variables (the presence of depressive personality disorder, the presence of axis I mood disorders in first-degree relatives, and age) and one dependent variable (the presence of dysthymia or major depression at follow-up) constituted the final regression model (likelihood ratio test, G=21.90, df=3, p<0.0001).

Post hoc stepwise logistic regression analyses, in which the presence/absence of depressive personality disorder was entered into the equation after the family history variable, were conducted to test whether the presence of depressive personality disorder mediated the effects of a family history of mood disorders.

Statistical significance was defined at the 0.05 level, two-tailed. SPSS 6.1 for Windows (25) with an additional Fisher’s exact test module was used for most computations except power calculations, which were done by Sigmastat 2.0 (26) and SamplePower 1.2 (27).

Results

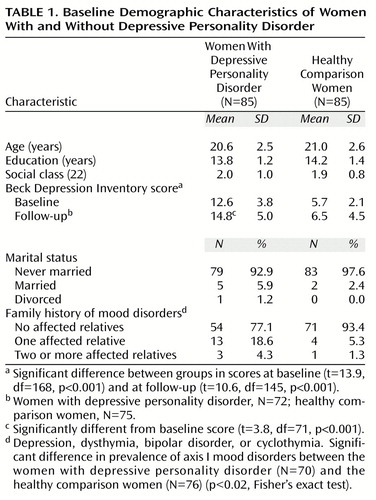

Baseline demographic characteristics for the two groups are summarized in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the women with and without depressive personality disorder in age, education, marital status, or social class at baseline. The prevalence rate of axis I mood disorders (major depression, dysthymia, bipolar disorder, or cyclothymia) in first-degree relatives was significantly greater in the women with depressive personality disorder than in the healthy comparison women. The women with depressive personality disorder had significantly greater mean Beck Depression Inventory scores than did the healthy comparison women, both at baseline and at follow-up (Table 1).

At follow-up, both the depressive personality disorder and the comparison groups did not differ significantly from baseline on age (after a 3-year correction for the follow-up interval), marital status, social class, and the prevalence of mood disorders in first-degree relatives.

For the women with depressive personality disorder, mean Beck Depression Inventory scores at follow-up were significantly greater than at baseline. However, when the same analysis was repeated after excluding the women with current major depression or dysthymia, there was no significant difference (t=1.86, df=60, p<0.07). For the healthy comparison women, there was no significant difference in mean Beck Depression Inventory scores between baseline and follow-up (Table 1).

Dysthymia

At the 3-year follow-up assessment, 14 (19.4%) of the 72 women with depressive personality disorder had developed dysthymia, whereas only three (4.0%) of the 75 healthy comparison women had. The women with depressive personality disorder had a significantly greater odds ratio for developing dysthymia at the 3-year follow-up than did the healthy comparison women after the presence of axis I mood disorders in first-degree relatives and age were controlled for (Table 2). The presence of axis I mood disorders in first-degree relatives was a significant confounding factor (odds ratio=4.75, 95% CI=1.31–17.20; Wald χ2=5.75, df=1, p<0.02) but was not an effect modifier in this regression model.

Major Depression

Five of the women with depressive personality disorder (6.9%) met the diagnostic criteria for current or lifetime major depression (the depressive episode of two of these subjects was superimposed on dysthymia) at follow-up, while one subject (1.3%) from the comparison group did. In the multivariate regression model for major depression, however, the odds ratio for developing major depression, relative to that of the healthy comparison women, of the women with depressive personality disorder did not reach statistical significance after the presence of axis I mood disorders in first-degree relatives and age were controlled for (Table 2). However, the CI for major depression skewed right, i.e., in the expected direction. The presence of axis I mood disorders in first-degree relatives was a significant confounding factor for developing major depression (odds ratio=8.07, 95% CI=1.19–54.87; Wald χ2=4.64, df=1, p<0.04) but was not an effect modifier in this regression model.

Axis I Unipolar Mood Disorders

At the 3-year follow-up assessment, 17 (23.6%) of the 72 women with depressive personality disorder experienced an axis I unipolar mood disorder (either dysthymia or major depression), whereas only four (5.3%) of the 75 healthy comparison women did. The women with depressive personality disorder had a significantly greater odds ratio for developing axis I unipolar mood disorders than did the healthy comparison women (odds ratio=4.16, 95% CI=1.24–13.91; Wald χ2=5.44, df=1, p=0.02) after age and the presence of axis I mood disorders in first-degree relatives were controlled for. The presence of axis I mood disorders in first-degree relatives was a significant confounding factor (odds ratio=7.08, 95% CI=2.06–24.38; Wald χ2=9.80, df=1, p=0.002) but was not an effect modifier in the regression model.

The powers for the comparison of the cumulative incidence rate of dysthymia, major depression, and any axis I unipolar mood disorder were 0.84, 0.41, and 0.89, respectively (power determined by normal approximation and precision computed by log method) (14).

At the 3-year follow-up assessment, there were no significant differences between women with and without depressive personality disorder in the cumulative incidence rates of bipolar disorder (N=1 and N=0, respectively), schizophrenia/other psychotic disorder (N=1 and N=0), psychoactive substance use disorders (N=3 and N=1), anxiety disorders (N=4 and N=1), somatoform disorders (N=3 and N=0), or eating disorders (N=4 and N=6).

Of the 72 women with depressive personality disorder at baseline, 53 (73.6%) retained the diagnosis at the 3-year follow-up assessment and 19 (26.4%) did not. Of the 75 healthy comparison women, six (8.0%) met criteria for depressive personality disorder at the 3-year follow-up assessment and 69 (92.0%) did not. These percentages of diagnostic retention revealed estimates of good diagnostic stability (diagnostic placement: kappa=0.66; total score on the Diagnostic Interview for Depressive Personality: ICC=0.72).

When we performed a logistic regression analysis that included only subjects whose diagnosis remained stable over the 3-year follow-up period, the women with depressive personality disorder had a significantly greater odds ratio for developing dysthymia than did the healthy comparison women (odds ratio=6.95, 95% CI=1.37–35.33; Wald χ2=5.58, df=1, p<0.02). However, the same set of analyses could not be performed for the risk of developing major depression, since the only subject who had major depression from the comparison group met depressive personality disorder criteria at follow-up.

Post hoc stepwise logistic regression analyses in which the presence/absence of depressive personality disorder was entered after the family history variable resulted in decreases in the following odds ratios. The odds ratio for the presence of dysthymia at follow-up fell from 7.27 (95% CI=2.09–25.28) to 4.75 (95% CI=1.31–17.20) (model difference: G=5.92, df=3, p<0.02). The odds ratio for the presence of major depression at follow-up fell from 11.97 (95% CI=1.86–76.97) to 8.07 (95% CI=1.18–54.87) (model difference: G=1.33, df=3, p<0.25). The odds ratio for the presence of any axis I unipolar disorder at follow-up fell from 10.47 (95% CI=3.16–34.68) to 7.08 (95% CI=2.06–24.38) (model difference: G=6.25, df=3, p<0.02). Details of the post hoc analyses are available upon request.

Discussion

Findings of the present study should be considered in light of the following limitations. First, the fact that our group of women with depressive personality disorder was selected from a nonclinical population of female college students may make it difficult to generalize our findings to a clinical setting. However, strict inclusion and exclusion criteria employed in the current study to ensure the absence of comorbid axis I or II disorders may help our findings better depict depressive personality disorder itself, since depressive personality disorder subjects, either in clinical or nonclinical settings, have been reported to have a high rate of comorbid axis I and axis II disorders (4, 5).

Second, a follow-up period of 3 years may not be long enough for detecting new development of axis I mood disorders in subjects with depressive personality disorder. However, the current study is the longest follow-up research to date; the follow-up periods of two previous studies were 1 year and 30 months (4, 5). In addition, the present study has the largest number of subjects with the sole diagnosis of depressive personality disorder at baseline and at follow-up (N=85 and N=72, respectively) and also included more healthy comparison subjects at baseline and at follow-up (N=85 and N=75, respectively). Our depressive personality disorder cohort would have been much greater (N=173) if we had included subjects with comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, as the previous follow-up studies of depressive personality disorder by Phillips et al. (4) and Klein and Shih (5) did. The number of subjects in the current study was roughly equivalent to or exceeded that of the previous follow-up studies (N=30 and 89, respectively), particularly with respect to the number of subjects with the sole diagnosis of depressive personality disorder. In addition, our comparison subjects had no axis I or axis II disorders, whereas those in prior follow-up studies did have various kinds of comorbid psychiatric disorders (4, 5).

Third, DSM-III-R criteria were used instead of those from DSM-IV, since instruments used in the current study were targeted for DSM-III-R diagnoses. Also, the diagnosis of depressive personality disorder was based on the Diagnostic Interview for Depressive Personality (11), the diagnostic criteria of which are not completely identical with those of DSM-IV (3). However, when we repeated the analyses with the DSM-IV depressive personality disorder criteria taken from the Diagnostic Interview for Depressive Personality (seven traits in the “depressive/negativistic” section of the interview correspond to the seven items listed under criterion A in DSM-IV), they did not produce significant differences in results. Details are not explained in this report.

Finally, the use of a Korean sample may make the current findings more difficult to generalize to other ethnic populations. However, previous studies of chronic low-grade depression in multiethnic populations, including one of Asian ancestry, did not find significant differences among ethnicities (28, 29). In addition, the validity of the depressive personality disorder construct and the reliability of the depressive personality disorder diagnosis were successfully tested in a recent large-scale study that used the Korean version of the Diagnostic Interview for Depressive Personality and included 89 psychiatric outpatients and 947 college students (unpublished 1999 study of Y-M Kim).

The mean Beck Depression Inventory scores of the women with depressive personality disorder at baseline and follow-up, excluding those with current dysthymia or major depression, corresponded to a rating of “mild” depression, whereas the scores of the healthy comparison women were in the normal range (21, 30, 31). This implies that depressive personality disorder subjects have a mild degree of depressive symptoms, although they did not meet the criteria for dysthymia or major depression. In addition, similar mean Beck Depression Inventory scores between baseline and follow-up, again excluding patients with current dysthymia or major depression, suggest that depressive personality disorder subjects have persistent low-grade depressive symptoms.

No previous studies have reported the odds ratio for developing dysthymia or major depression, relative to that of healthy comparison subjects, in subjects with depressive personality disorder. The current finding that women with depressive personality disorder had a significantly greater odds ratio for developing dysthymia at 3-year follow-up than did healthy comparison women is in accordance with our a priori hypothesis. In addition, the same result, produced by an additional logistic regression analysis that used only subjects whose diagnosis remained stable over the follow-up period, adds to the stability of this finding. Taken together, these results add support to the perspective that places depressive personality disorder as a characterological variant of axis I unipolar mood disorders.

The odds ratio for developing major depression, relative to that of healthy comparison subjects, in subjects with depressive personality disorder did not reach statistical significance. However, readers should be cautious in interpreting this negative finding, since the power for detecting differences for major depression was relatively low compared to that for dysthymia or any axis I mood disorders.

When the odds ratio for developing either dysthymia or major depression was tested, the women with depressive personality disorder had a significantly greater odds ratio for developing these axis I unipolar mood disorders than did the healthy comparison women. However, the change in the odds ratio and the Wald statistic suggests that this relationship between depressive personality disorder and any axis I mood disorders may be driven largely by the relationship between depressive personality disorder and dysthymia.

The fact that the presence of axis I mood disorders in first-degree relatives was a significant confounding factor in all three regression models is in accordance with previous reports that family history of mood disorders is a significant risk factor for depressive disorders (32). Although family history did not have a modifying effect on the relationship between depressive personality disorder and dysthymia from the perspective of statistical models, the possibility that depressive personality disorder may mediate the relationship between family history and mood disorder should be considered, since depressive personality disorder has long been considered as a personality core of depressive spectrum disorders (6).

Thus, results from the post hoc stepwise logistic regression analyses strongly suggest that a family history of mood disorder may be mediated by the presence of depressive personality disorder. This implies that depressive personality disorder may serve as an important risk factor and early indicator of axis I mood disorders.

The diagnostic stability of depressive personality disorder (kappa=0.66 and ICC=0.72) in our study was relatively higher than that seen in previous studies (Phillips et al. [4]: kappa=0.55 and ICC=0.62; Klein and Shih [5]: kappa=0.37 and ICC=0.51). These differences in diagnostic stability estimates may stem from 1) the presence or absence of axis I or axis II comorbidity in the depressive personality disorder and comparison subjects; 2) differences in severity of depressive symptoms and, consequently, the subsequent treatment; and 3) imperfect interrater reliabilities.

Ferro et al. (33) recently reported that kappa values for the 30-month diagnostic stability of DSM-III-R personality disorders ranged from 0.24 to 0.54 and ICC values ranged from 0.22 to 0.65. Temporal stability estimates of depressive personality disorder diagnosis from the current and previous studies of depressive personality disorder (4, 5) are comparable to those of other personality disorders.

Previous studies have reported that comorbid personality disorders, in general, negatively influence the treatment outcome of major depression (34) and that the presence of depressive personality disorder in depressed subjects is related to a greater severity of depression at follow-up assessments (5). The possible influence of prior presence of depressive personality disorder on the course and prognosis of dysthymia or major depression should be evaluated in future studies.

The current findings need to be replicated in future studies with more subjects, longer follow-up periods, and in subjects with different demographic characteristics. In conclusion, this study, the 3-year follow-up results of an ongoing project regarding the course of depressive personality disorder, found that women with depressive personality disorder were at a higher risk for developing dysthymia—and possibly major depression—than were a group of healthy comparison women. In addition, our findings suggest that a family history of axis I unipolar mood disorders may be mediated by the presence of depressive personality disorder. Clinicians and the general public should be aware of the clinical significance of depressive personality disorder, since subjects with nonclinical depressive symptoms or those with dysthymia are at greater risk for developing major depression (35–37).

|

|

Presented in part at the special lectures at Kyunghee and Korea University Colleges of Medicine, Seoul, May 20 and September 25, 1998, and at the 43rd annual meeting of the Korean Neuropsychiatric Association, Seoul, October 22–23, 1998. Received July 6, 1999; revisions received Jan. 6 and June 16, 2000; accepted July 17, 2000. From the Departments of Psychiatry and Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Clinical Research Institute, Seoul National University Hospital and College of Medicine; the Department of Psychology, Inje University College of Medicine, Seoul; the Department of Health Science, Dongduk Women’s University, Seoul; the Departments of Psychiatry at Korea University College of Medicine, Kyunghee University College of Medicine, and Samsung Medical Center, Seoul; and the Department of Psychology, Hallym University, Kangwon-do, South Korea. Address reprint requests to Dr. Lyoo, Department of Psychiatry, Seoul National University Hospital, Yongon-dong 28, Chongno-gu, Seoul, South Korea 110-744. Supported by grants from the Seoul National University Hospital (4-98-040), the Yoohan Public Health Fund, and Inje University. The authors thank Soo-Jung Han, M.A., and Kelley Y. Abrams, Ph.D., for their assistance with the preparation of this article.

1. Lyoo IK, Gunderson JG, Phillips KA: Personality dimensions associated with depressive personality disorder. J Personal Disord 1998; 12:46–55Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Akiskal HS: Dysthymic disorder: psychopathology of proposed chronic depressive subtypes. Am J Psychiatry 1983; 140:11–20Link, Google Scholar

3. Hirschfeld RMA, Holzer CE: Depressive personality disorder: clinical implications. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55(April suppl):10–17Google Scholar

4. Phillips KA, Gunderson JG, Triebwasser J, Kimble CR, Faedda G, Lyoo IK, Renn J: Reliability and validity of depressive personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1044–1048Google Scholar

5. Klein DN, Shih JH: Depressive personality: associations with DSM-III-R mood and personality disorders and negative and positive affectivity, 30-month stability, and prediction of course of axis I depressive disorders. J Abnorm Psychol 1998; 107:319–327Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Phillips KA, Gunderson JG, Hirschfeld RMA, Smith LE: A review of the depressive personality. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:830–837Link, Google Scholar

7. Klein DN, Miller GA: Depressive personality in nonclinical subjects. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1718–1724Google Scholar

8. Widiger TA: The categorical distinction between personality and affective disorder. J Personal Disord 1989; 3:77–91Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Shea MT, Hirschfeld RMA: Chronic mood disorder and depressive personality. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1996; 19:103–120Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Keller MB, Hanks DL, Klein DN: Summary of the DSM-IV mood disorders field trial and issue overview. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1996; 19:1–28Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Gunderson JG, Phillips KA, Triebwasser J, Hirschfeld RMA: The Diagnostic Interview for Depressive Personality. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1300–1304Google Scholar

12. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Patient Version (SCID-P). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1990Google Scholar

13. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Chauncey DL, Gunderson JG: The Diagnostic Interview for Personality Disorders: interrater and test-retest reliability. Compr Psychiatry 1987; 28:467–480Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988Google Scholar

15. Lyoo IK, Hong KE, Cho DY: Effects of the family environment and the biogenetic temperament/character on the emotional and behavioral aspects of the filial piety. J Korean Neuropsychiatric Assoc 1998; 37:921–931Google Scholar

16. Lyoo IK, Han MH, Cho DY: A brain MRI study in subjects with borderline personality disorder. J Affect Disord 1998; 50:235–243Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Non-Patient Edition (SCID-NP, Version 1.0). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1989Google Scholar

18. Bartko JJ, Carpenter WT Jr: On the methods and theory of reliability. J Nerv Ment Dis 1976; 163:307–317Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Zanarini MC: Revised Family History Questionnaire. Belmont, Mass, McLean Hospital, Psychosocial Research Program, 1990Google Scholar

20. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J: An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961; 4:561–571Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Shin MS, Kim ZS, Park KB: The cut-off score for the Korean version of Beck Depression Inventory. Korean J Clin Psychol 1993; 12:71–81Google Scholar

22. Hollingshead AB, Redlich FC: Social Class and Mental Illness: A Community Study. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1958Google Scholar

23. Hwang ST, Cho YG, Oh DY, Kim CH, Yang BH: Content validity of DSM-III-R personality disorder. J Korean Neuropsychiatric Assoc 1996; 35:290–297Google Scholar

24. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S: Model-building strategies and methods for logistic regression, in Applied Logistic Regression. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1989, pp 82–134Google Scholar

25. SPSS 6.1 for Windows. Chicago, SPSS, 1995Google Scholar

26. Sigmastat for Windows version 2.0. San Rafael, Calif, Jandel Corp, 1995Google Scholar

27. SamplePower 1.2. Chicago, SPSS, 1997Google Scholar

28. Prescott CA, McArdle JJ, Hishinuma ES, Johnson RC, Miyamoto RH, Andrade NN, Edman JL, Makini GK Jr, Nahulu LB, Yuen NY, Carlton BS: Prediction of major depression and dysthymia from CES-D scores among ethnic minority adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998; 37:495–503Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Takeuchi DT, Chung RCY, Lin K-M, Shen H, Kurasaki K, Chun C-A, Sue S: Lifetime and twelve-month prevalence rates of major depressive episodes and dysthymia among Chinese Americans in Los Angeles. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1407–1414Google Scholar

30. Beck AT: Depression: Causes and Treatment. Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1972Google Scholar

31. Lee YH, Song JY: A study of the reliability and the validity of the BDI, SDS, and MMPI-D scales. Korean J Clin Psychol 1991; 10:98–113Google Scholar

32. McGuffin P, Katz R, Aldrich J, Bebbington P: The Camberwell Collaborative Depression Study, II: investigation of family members. Br J Psychiatry 1988; 152:766–774Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Ferro T, Klein DN, Schwartz JE, Kasch KL, Leader JB:30-month stability of personality disorder diagnoses in depressed outpatients. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:653–659Google Scholar

34. Shea MT, Pilkonis PA, Beckham E, Collins JF, Elkin I, Sotsky SM, Docherty JP: Personality disorders and treatment outcome in the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:711–718Link, Google Scholar

35. Kovacs M, Feinberg TL, Crouse-Novak M, Paulauskas SL, Pollock M, Finkelstein R: Depressive disorders in childhood, II: a longitudinal study of the risk for a subsequent major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:643–649Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Crum RM, Cooper-Patrick L, Ford DE: Depressive symptoms among general medical patients: prevalence and one-year outcome. Psychosom Med 1994; 56:109–117Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Angst J: Comorbidity of mood disorders: a longitudinal prospective study. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1996; 30:31–37Medline, Google Scholar