Family Focused Grief Therapy: A Randomized, Controlled Trial in Palliative Care and Bereavement

Abstract

Objective: The aim of family focused grief therapy is to reduce the morbid effects of grief among families at risk of poor psychosocial outcome. It commences during palliative care of terminally ill patients and continues into bereavement. The authors report a randomized, controlled trial. Method: Using the Family Relationships Index, the authors screened 257 families of patients dying from cancer: 183 (71%) were at risk, and 81 of those (44%) participated in the trial. They were randomly assigned (in a 2:1 ratio) to family focused grief therapy (53 families, 233 individuals) or a control condition (28 families, 130 individuals). Assessments occurred at baseline and 6 and 13 months after the patient’s death. The primary outcome measures were the Brief Symptom Inventory, Beck Depression Inventory, and Social Adjustment Scale. The Family Assessment Device was a secondary outcome measure. Analyses allowed for correlated family data and employed generalized estimating equations based on intention to treat and controlling for site. Results: The overall impact of family focused grief therapy was modest, with a reduction in distress at 13 months. Significant improvements in distress and depression occurred among individuals with high baseline scores on the Brief Symptom Inventory and Beck Depression Inventory. Global family functioning did not change. Sullen families and those with intermediate functioning tended to improve overall, whereas depression was unchanged in hostile families. Conclusions: Family focused grief therapy has the potential to prevent pathological grief. Benefit is clear for intermediate and sullen families. Care is needed to avoid increasing conflict in hostile families.

Systematic reviews of interventions with family caregivers during palliative care and bereavement reveal strikingly weak effects in efficacy studies (1 – 3) . Grief counseling is not helpful for all; for many it may be intrusive and, indeed, unwarranted (4) . For the oft-recommended group therapies, disappointing results come from heterogeneity of membership, lack of prescreening, and inexperienced facilitators (2) . In a meta-analysis of the outcome for palliative care and hospice teams, the slightly positive effect achieved for index patients contrasted starkly with no benefit for caregivers and family members (5) .

A consensus has emerged that generic interventions delivered to the broad population of the bereaved are unnecessary and that preventive interventions should target high-risk caregivers and mourners (6) . The fundamental clinical questions have been how to recognize those at risk and what type of intervention to then offer.

Given this background and the reality that life-threatening illness causes distress to reverberate through the family, a family-centered approach has appeared apt for palliative care. Our research over the past decade has led us to develop a model we have named “family focused grief therapy,” in which the functioning of the family is screened routinely when the patient is admitted to a service in order to identify families at risk of morbid psychosocial outcome as a result of how members relate together. We then offer these families an intervention aimed at harnessing their inherent strengths and bolstering their capacity to cope adaptively.

In this article we present the results of a randomized, controlled trial of family focused grief therapy involving 81 families (362 individuals), designed to test the efficacy of our model.

Classification of Family Functioning

In past research, we devised a typology of family functioning during palliative care and bereavement using the short form of the Family Environment Scale (7) , which differentiates families into well-functioning, intermediate, and dysfunctional classes (8 , 9) . Of the 10 subscales forming the Family Environment Scale, only three were found in our cluster analytic work to differentiate families by this typology (10 , 11) . These three are known as the Family Relationships Index and are based on members’ perceptions of the family’s cohesiveness, expressiveness, and capacity to deal with conflict. Two classes have good functioning. “Supportive” families are characterized by very high levels of cohesion, and “conflict resolvers” tolerate differences of opinion and deal with conflict constructively through effective communication. These families have low levels of psychosocial morbidity and do not appear to require professional psychotherapy.

Two classes are clearly dysfunctional. “Hostile” families tend to reject help and are distinguished by high conflict levels, poor cohesion, and poor expressiveness. “Sullen” families carry moderate impairments across these three domains; their muted anger and desire for help are noteworthy. These dysfunctional families have high rates of psychosocial morbidity, including clinical depression. Of the families of patients receiving palliative care, 15%–20% are dysfunctional, and the rate increases to 30% during the initial phase of bereavement (11) .

Between these well-functioning and poorly functioning groups is a class of families who exhibit moderate cohesiveness but are still prone to psychosocial morbidity. Their functioning has been termed “intermediate” and tends to deteriorate under the strain of death and bereavement.

Family focused grief therapy is grounded on the key observation that the dysfunctional and intermediate classes carry the substantial psychosocial morbidity found during palliative care and bereavement (12) . Rather than treating each family member individually, family focused grief therapy offers a systemic approach and has the advantage that it can be applied preventively.

At-risk families are identified through screening with the short form of the Family Relationships Index (7) , a 12-item self-report measure completed independently. We found its sensitivity to be 86% (13) ; an independent group reported 100% sensitivity to detect family dysfunction and 88% to detect clinical depression (14) . The Family Relationships Index is unlikely to miss those at risk, although its poorer specificity leads to a number of false positives. We refrain from attributing pathology to families in any way since screening is not diagnostic but only points to those at risk. Given the importance we attach to assisting families as they care for their dying relative, the family is invited to meet with a therapist.

Family Focused Grief Therapy

Family focused grief therapy is a brief, focused, and time-limited intervention typically comprising 4–8 sessions of 90 minutes’ duration, which are arranged flexibly across 9–18 months. We initially created a manual for conducting the therapy and then published this in a book as a series of guidelines, together with many clinical illustrations (15) . The intervention aims to prevent the complications of bereavement by enhancing the functioning of the family, through exploration of its cohesion, communication (of thoughts and feelings), and handling of conflict. The story of illness and related grief is shared in the process. Family focused grief therapy has three phases: 1) assessment (one or two weekly sessions) concentrates on identifying issues and concerns relevant to the specific family and on devising a plan to deal with them, 2) intervention (typically two to four sessions) focuses on the agreed concerns, and 3) termination (one or two sessions) consolidates gains and confronts the end of therapy. The frequency and number of sessions in each phase are modified to meet the needs of each family.

Method

We coordinated this multisite, randomized, controlled trial at the University of Melbourne’s Centre for Palliative Care, located in St. Vincent’s Hospital and the Peter MacCallum Cancer Institute, Melbourne. Other participating centers were three hospice home-care services: Bethlehem Hospital’s Community Palliative Care Service, Eastern Palliative Care, and Mercy Western Palliative Care. We obtained approval from the ethics committees of all participating centers. All patients and family members gave written informed consent.

Participants

Patients and their relatives recruited between 1996 and 2001 were eligible for the trial if the treating physician gave a prognosis of 6 months and agreed to the study. Other inclusion criteria included patient age between 35 and 70 years, adequate command of English, geographical accessibility, a living partner, and one or more children more than 12 years old. This last requirement was necessary so that children would be able to complete the questionnaires; while our focus was on adult patients with cancer, the young and very elderly bring unique clinical issues deserving of separate studies. As already mentioned, only families at risk of poor psychosocial outcome were eligible. On the basis of our earlier work, a score of less than 4 on cohesiveness or a total score of 9 or less on the Family Relationships Index was the cutoff level (15 , p. 43). Recruitment thus entailed obtaining consent in two stages—for screening patients and relatives and for study entry. Each member had to consent individually to participate.

Data at baseline and follow-up (6 and 13 months postbereavement) were obtained from relatives independently by a research assistant; details of the baseline data have been published elsewhere (13) .

The families were assigned to functional classes according to rules established in our earlier research on the typology of family functioning (12) . Since well-functioning families were ineligible, they were eliminated through screening. Dysfunctional (hostile and sullen) and intermediate families were classified on the basis of the poorest perception of family functioning of any member on the Family Relationships Index. This criterion is in accord with the clinical observation that a single member may be the “symptom bearer”; use of average scores to assign families would reduce recognition of potentially at-risk families. We deliberately give greater priority to sensitivity than to specificity in order to obviate missing such families.

Intervention and Control Conditions

Our 16 therapists were social workers who were all qualified family therapists and received standardized training consisting of a detailed review of the therapy manual (15) , two half-day workshops about the family focused grief therapy model, and supervision (by D.W.K. and S.B.) of each session with a pilot family before participating in the trial (12) .

Each therapy session was audiotaped and later reviewed by the therapist, who prepared a 3–4-page summary of themes and interventions from each session. The therapists met weekly as a peer group with the supervisors throughout the pilot study and subsequent trial, discussing these process notes to monitor competence and ensure adherence to the model.

An analysis of fidelity to the intervention was conducted independently (16) . Interrater reliability was assessed with an integrity measure for family focused grief therapy (16) and proved satisfactory, with 88% overall agreement. Faithful adherence to the core elements of the model was achieved by 86% of the therapists. Their competence was evidenced by a strong therapeutic alliance (94%), affirmation of family strengths (90%), and focus on agreed-upon themes (76%). The therapists averaged 10 grief-related questions per session, seven on communication-related issues during assessment, seven on conflict late in therapy, and four on cohesiveness across the course of therapy.

Therapy was conducted in the hospital or, more commonly, in the family home in an effort to accommodate ill patients. Although the problems and challenges associated with therapy in the home are well documented, the patient’s home is emerging as a much-appreciated site (17) .

Families in the control arm did not receive any formal psychological treatment beyond the standard palliative care provided by home-care programs, which did involve counseling when deemed clinically appropriate. We therefore carefully logged for later comparison this “standard palliative care” received by both arms, including visits to a general practitioner, counseling, and use of antidepressants, hypnotics, tranquilizers, and alcohol.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was psychosocial functioning in bereaved family members, particularly levels of distress, depression, and social adjustment, which are pertinent in assessing complicated bereavement. A secondary outcome was family functioning. The patients and relatives completed a series of measures at baseline, and then the relatives repeated these and completed a bereavement measure at 6 and 13 months after the patient’s death; the latter was timed to avoid the first anniversary. In the unusual event that the therapy was concluded but death had not occurred as expected, outcome assessments were completed 6 and 13 months after therapy completion. A semistructured interview was conducted to obtain demographic, illness, and family information from each patient and the relatives independently.

Group Size

Calculation of the number of subjects employed the GPOWER procedure (18) and was based on achieving a medium effect size of 0.50 as defined by Cohen (19) , an average of four members per family with a medium (r s =0.30) intercorrelation (13) between family member responses, and a 2:1 ratio of random assignment to treatment and control groups. With a type I error of 0.05 (two-tailed), as recommended by Bird and Hall (20) , a group of 75 families would yield a power of 84%. We therefore aimed to recruit 80 families, thus allowing for potential dropouts.

Randomization

Randomization was performed independently by the statistical service of the Peter MacCallum Cancer Institute, using a computer-generated table of random numbers to make the allocation in the 2:1 ratio, stratifying by recruitment site. When a family was allocated to the intervention, the research assistant assigned the next available therapist to them.

Masking

No blinding was used in the randomization or data collection. Data were entered by a research assistant who had no knowledge of group assignment. Fidelity of intervention, as already discussed, was examined by research assistants blinded to the therapist identity, families, and supervision process. Gradual familiarity with the voice of a therapist, however, limits such blinding processes in psychotherapy trials.

Measures

The short form of the Family Environment Scale (7) is a well-validated measure of an individual’s perception of the family’s functioning. The similarity of profiles obtained by using only four items from each subscale (short form, form S, 40 items) and by using the complete nine items (form R, 90 items) was investigated by using intraclass correlations and was found to be satisfactory (7) . The 40-item short form has 10 subscales and has demonstrated consistency, stability, and predictive and discriminant validity (21) . Three of these subscales—cohesiveness, conflict, and expressiveness (of thought and feeling)—form the Family Relationships Index, a global measure of relational interaction within the larger family environment. The Family Relationships Index (12 items) was used for screening, and the Family Environment Scale (40 items) was administered to family members enrolling in the trial.

The Family Assessment Device, a 60-item measure based on the McMaster model of family functioning, assesses the accomplishment of essential functions and tasks that distinguish “healthy” from “unhealthy” families (22) . We used its general functioning scale as an independent outcome measure, since the Family Environment Scale had been part of the criteria for determining study entry. The Family Assessment Device has good internal consistency and discriminant validity (23) .

The Brief Symptom Inventory (24) is derived from the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-90 and yields ratings of general psychological morbidity. Its general severity index was used as a primary outcome measure. The Brief Symptom Inventory has impressive reliability and validity, both convergent and predictive (25) .

The cognitive items of the Beck Depression Inventory constitute its short form, which correlates satisfactorily with the full version and eliminates somatic items that are confounding in the medically ill (26) . More than 40 years of psychometric evaluation confirm its reliability and validity (27) .

The Social Adjustment Scale is derived from its well-validated predecessor for use as a measure of change in domains of housework, work, social and leisure activities, relationships with children and extended family, and overall social functioning (28) . We used its global score.

The Bereavement Phenomenology Questionnaire is a 22-item measure of the normal phenomena of grief, such as nostalgia and remembering. It has good internal consistency and validity and was used to differentiate normal grief expressions from more morbid forms of distress and depression (29 , 30) .

Sociodemographic characteristics of the patients and their family members were documented; these included age, gender, occupation and current work status, marital status, religion, religious practice, and country of birth. Information on each patient’s and family member’s health and service utilization was collected. Tumor type, major categories of anticancer treatment, and dates of diagnosis and of death were ascertained from each patient’s medical record.

Statistical Analysis

Length of illness from diagnosis to death and survival from study entry to death were calculated by using the Kaplan-Meier procedure for estimating time-to-event occurrences in the presence of censored cases (31) .

In order to account for possible correlation between the responses of the family members (5 – 7) , we applied statistical methods specifically developed for clustered data. For comparisons of sociodemographic characteristics in the two study arms, we utilized Pearson chi-square statistics, corrected for family dependence in scores (32) . Generalized estimating equations (33) , adjusting for site, were employed to examine change from baseline to 13 months postdeath (or termination, if the patient had not died) in each arm and then from baseline to 6 months postdeath (or termination). In separate analyses the difference in a measure between assessments was modeled as a function of a binary variable indicating whether the family member received the intervention. An identity link function was used together with the Huber-White robust sandwich variance estimate (34) with an independent covariance matrix; p values are from robust Wald statistics. For our three primary outcome variables, significance was set at 0.017.

In order to ascertain whether family members with missing data differed significantly from those with complete data, we used generalized estimating equations with a binary variable indicating missed assessments. In separate univariate analyses, these binary variables were modeled as a function of baseline assessments and classification of family functioning by using robust sandwich variance estimates with an independent working covariance matrix. When a statistically significant difference was observed between members with missing and complete data, the binary variable indicating group membership and the interaction term were included to assess whether the pattern differed significantly between the intervention and control groups.

We used an intention-to-treat approach for all analyses. Data from five patients who did not die were included in the follow-up assessments. All analyses were conducted with the statistical software package Stata (Intercooled Stata 8.0 for Windows, Stata Corp., College Station, Tex.). The Stata procedure SVYTAB was used for comparisons of sociodemographic characteristics, and XTGEE was used for analyses with generalized estimating equations.

Results

Participants and Follow-Up

Of 483 eligible families, 257 (53%) were screened, and the Family Relationships Index was completed by 701 individuals. As shown in Figure 1 , the reasons for not screening eligible families included refusal to consent, inaccessibility, and avoidant behaviors. Of the 130 families who refused screening, 86 appeared to be avoidant, citing lack of interest, being too busy or not having time, or not wanting family sessions. Other reasons given for not participating were a patient who was too unwell or recently hospitalized, a chaotic or alienated family, and the perception that the family was coping well. Families classified as chaotic or alienated included those with too much going on or an inability to organize the family to come together.

Of the 257 families consenting to be screened, 74 (29%) were classified as well functioning (and thus ineligible for the trial), 121 (47%) were classified as intermediate in functioning, and 62 (24%) were categorized as dysfunctional. Of 183 eligible families, 81 (44%) gave informed consent, generating a cohort of 363 individuals ( Figure 1 ). Eastern Palliative Care and St. Vincent’s Hospital were the biggest sources of patients for this trial, contributing 33 and 25 families, respectively. Thirteen families were recruited from Mercy Western Palliative Care, six from Bethlehem Hospital’s Community Palliative Care Service, and four from Peter MacCallum Cancer Institute.

The most common tumor types present in the index patients were breast (25%), lung (20%), brain (12%), colorectal (9%), pancreas (7%), esophageal (5%), prostate (4%), and other (18%). Most patients had received chemotherapy (84%) and radiotherapy (74%); hormone therapy had been given to 15% as an anticancer treatment.

The mean age of the patients in the trial was 57 years (SD=8). The mean age of their spouses was 56 years (SD=9), and for their offspring it was 29 years (SD=9). The mean age of other family members was 32 years (SD=10). In 5% of the families there was one child, in 51% there were two children, in 33% there were three children, and 11% of the families had four or more children.

In the final cohort, 51% of the families were classified as having intermediate functioning, 26% were designated sullen, and 23% were categorized as hostile. Baseline sociodemographic characteristics of the patients and their family members have been published previously (13) . The median length of illness from diagnosis to death was 25 months, and the median survival time from study entry to death was 96 days. No significant differences were found between the control and intervention arms on any sociodemographic variable at baseline ( Table 1 ).

Of the 81 randomly assigned families, 53 were allocated to the intervention and 28 were assigned to the control condition. Within the former, 45 families (85%) had family focused grief therapy; two withdrew after one session, three withdrew before termination, and 40 (76%) completed therapy as planned. The two families who dropped out early were dissatisfied with the family meeting; the families departing later did participate in key treatment sessions. On an intention-to-treat basis, the median number of sessions was 4, the mean was 3.8, and the range was 0 to 13. For those completing family focused grief therapy, the families with intermediate functioning averaged 7.0 sessions (range=3–13), the sullen families received 6.4 (range=4–9), and the hostile families completed a mean of 9.4 (range=7–13). The number of families for whom data were available for analysis varied between 72 and 78 families, depending on the measure under consideration.

There were 61 family members who missed assessments of measures: 38 in the intervention group (21%) and 23 in the control group (22%). The main patterns of missing observations (accounting for 85%) were family members who contributed data only at baseline (29 individuals) or at baseline and 6 months postdeath but not at the last assessment (23 individuals). Members with missing data had significantly poorer family functioning according to the baseline score on the Family Assessment Device general functioning scale (p=0.03, robust Wald test) and the Family Relationships Index (p=0.02, robust Wald test). These patterns did not differ significantly between the intervention and control arms.

Distress, Depression, and Social Adjustment

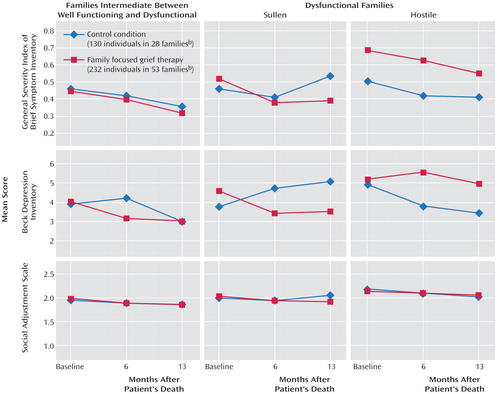

Using generalized estimating equations to compare the mean changes in the intervention and control groups for all family members from baseline to 6 months and baseline to 13 months, we found that distress as measured by the general severity index of the Brief Symptom Inventory showed nonsignificantly greater improvement at 13 months in the participants receiving family focused grief therapy than in the control group ( Table 2 ). Grief phenomena, measured with the Bereavement Phenomenology Questionnaire, diminished similarly in both arms. The changes in depression (Beck Depression Inventory) and social adjustment (Social Adjustment Scale) did not differ significantly; the patterns of change for these primary outcome variables are presented in Figure 2 .

a Control condition consisted of standard palliative care provided by home-care programs, which involved counseling when clinically appropriate.

b Number of individuals varied because of missing data for some family members.

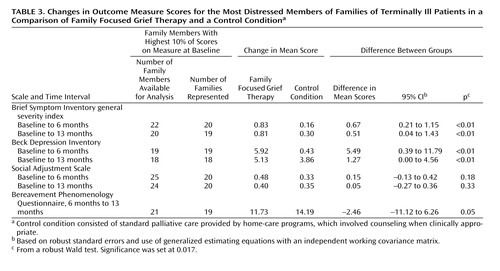

Given the potential masking of change in family members with pathological grief by the central tendency present when the cohort is examined as a whole, analyses were also carried out on the top 10% of family members with the most distress, depression, and poor social adjustment at baseline ( Table 3 ). Significant improvement in distress and depression, but not social adjustment, at both 6 and 13 months was evident for those receiving family focused grief therapy. By way of a hypothesis-generating exploration, we examined the differences among family types. The most noteworthy improvement in distress and depression occurred in members of sullen families ( Figure 3 ), but the numbers in these cells were small (14 families receiving the intervention and eight control families). It is noteworthy that depression remained unchanged in the hostile families receiving family focused grief therapy but decreased in the control group.

a Control condition consisted of standard palliative care provided by home-care programs, which involved counseling when clinically appropriate. Family functioning was determined according to a previously established typology (12). Well-functioning families were not eligible for this trial.

b Number of individuals varied because of missing data for some family members.

For the gain in score on the Brief Symptom Inventory general severity index at 13 months for families receiving family focused grief therapy, the effect size was small (d=0.26). Sullen families (d=0.32) fared better with the intervention than the families with intermediate functioning (d=0.19) or hostile families (d=0.18). Similarly, for the Beck Depression Inventory at 6 months, the effect size for sullen families (d=0.44) was better than that for the intermediate families (d=0.30).

No statistically significant differences were found between the intervention and control arms in the proportions of patients who saw a general practitioner, received other forms of counseling, took antidepressants, hypnotics, or tranquilizers, or consumed more alcohol. No significant association was found between the therapist and outcome or between duration of therapy and outcome.

Family Functioning

No statistically significant differences between the two arms were found on the secondary outcome measures, i.e., the Family Assessment Device general functioning scale or the Family Environment Scale ( Table 2 ). In another hypothesis-generating exploration, families with intermediate functioning who received family focused grief therapy had a significantly larger reduction in conflict level on the Family Environment Scale at 6 months than the intermediate families in the control group (123 individuals, 38 families); the difference between groups in score changes was 0.44, and the 95% confidence interval (CI) was 0.04 to 0.83 (p=0.03). Hostile families receiving family focused grief therapy deteriorated significantly more than the hostile control families over 13 months (48 individuals, 17 families); the difference between groups in change on the Family Environment Scale conflict scale was –0.80 (95% CI=–1.25 to –0.33, p=0.001).

Discussion

Family focused grief therapy reduced the complications of bereavement, with a greater reduction of general distress (Brief Symptom Inventory) over 13 months and a significant reduction of distress and depression (Beck Depression Inventory) for the 10% of family members with high baseline scores. These gains were not accompanied by better social functioning. The intensity of grief (Bereavement Phenomenology Questionnaire) waned similarly in both arms. The Bereavement Phenomenology Questionnaire is a measure of the expressions of grief. The intended benefit of family focused grief therapy was not directed at normal grief but toward preventing pathological grief. The latter is expressed clinically in terms of depressive and related disorders. We have avoided being drawn into the current debate about “complicated grief,” which is being applied to a form of chronic grief (35) . The striking outcome of this randomized, controlled trial was the improvement achieved in family members who had elevated distress and depression scores at baseline.

Social functioning is expressed across several functional domains. While improved social functioning is desirable, it was perhaps too ambitious a goal. The trial may not have included enough individuals with poor initial social functioning to be sufficiently powered to demonstrate change, but the direction of differential benefit is clear ( Table 3 ).

It is interesting that the protection against pathological grief was accomplished without a comparable gain in family functioning. Indeed, given the demands of bereavement, scores on the Family Assessment Device and the Family Environment Scale deteriorated slightly, especially over the first 6 months. This pattern was previously noted in our longitudinal study of bereaved families (10) . This discrepancy between clinical benefit among family members and their perception of family functioning may be explained in several ways. One explanation is that impressions of family functioning may take longer to change given entrenched beliefs about what the family is truly like. Since the death of a relative inevitably perturbs family interactions, family therapy may not realistically be able to prevent a degree of disruption. Nevertheless, professionally led attention to family cooperation and communication may confer some protection. Our findings suggest that some containment occurs.

A further possibility lies in the nature of the measures used; the perceptions of functioning that they capture may be trait rather than state characteristics and thus less sensitive to change. Some studies using the Family Assessment Device have raised questions about which subscales differentiate groups most effectively (36) . In this debate, Ridenour and colleagues (37) argued for two higher-order factors: collaboration and commitment. In our trial, the Family Assessment Device may have been tapping into family dimensions different from the focus of our therapy.

Sullen families derive the most benefit from family focused grief therapy. Our earlier work highlighted their motivation to seek help and their high rates of psychosocial morbidity. Although the small number of sullen families in this trial precludes definitive conclusions, our results ( Figure 3 ) suggest that this family type is most suited to a family intervention such as family focused grief therapy.

In contrast, our findings offer an important caveat about the role of family focused grief therapy in hostile families. While this intervention appeared to reduce conflict in these families over 6 months, this was reversed at 13 months; hostile families in the control arm, on the other hand, steadily improved. The potential to cause harm serves as a timely warning that therapists may not be able to rescue these families from their long-standing patterns of conflict and alienation. Our guidelines did caution therapists not to believe they could work miracles for these families; we set modest goals of support related to the illness. We surmise that hostile families may be best treated individually, with family meetings being confined to planning and provision of care for their dying relative.

Family focused grief therapy offers a modest prospect of benefit for families with intermediate functioning. Conflict tended to increase in the control families in this class, whereas it declined in those receiving treatment across 6 months, with distress correspondingly diminished. One limitation to the generalizability of these findings is the variation among the family types in the rates of those consenting to the study: from eligible families, 79% of hostile, 55% of sullen, and only 34% of intermediate families could be enrolled ( Figure 1 ). Although avoidance-related reasons dominated among the study refusers, when families perceive any disturbance in their functioning to be mild, they may be disinclined to commit to family therapy.

No link emerged between therapist and outcome, suggesting that the model can be taught to, and mastered by, family therapists in general. Duration of therapy was also not related to outcome. The relative brevity of family focused grief therapy is noteworthy for the potential gains from this focused intervention. Given the universal difficulty of funding psychosocial programs in cancer services, such cost-effectiveness is a distinct advantage.

Family approaches to the management of grief have been neglected in psychotherapy research. Our trial offers preliminary evidence about the population likely to be helped and a model that meets their needs. However, the differential impact on sullen and intermediate families on the one hand and hostile families on the other reminds us that we have not discovered a panacea. Indeed, meta-analyses of psychological interventions for the bereaved reveal weak effect sizes (1 – 3) . Limited gains were found in but two of eight studies of group approaches and in three of four individual interventions. In our own review of four studies of family-based interventions, only two were helpful (38) . Since that review, a cognitive behavior family intervention that reduced the burden of care in relatives of patients with Alzheimer’s disease has been reported (39) . In contrast, a major Norwegian study that randomly assigned participants to comprehensive palliative care and conventional oncological care showed no difference in bereavement outcome (40) . The challenge in devising a model of preventive care for the bereaved has been substantial.

A key conceptual difference in our approach is in identifying at-risk families as the target of attention (41) . We used a screening process for this purpose that, in itself, encountered avoidance as a prime reason for refusal to participate. Of the 183 families eligible for the trial, only 44% consented, with both avoidant and chaotic/alienated families prominent among those declining. Routine screening of family functioning as part of a comprehensive program of palliative care would allow a family-centered model of care, an approach synchronous with recommendations of the Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry’s Committee on the Family (42) . At this stage, the sizable refusal rate remains a limitation of this study. Neimeyer echoed this in describing the many inherent challenges to the grief researcher (43) . On the other hand, our caveat concerning hostile families points to the need to go beyond a unitary approach.

Clinical and Research Implications

Bereavement care should begin during palliative care and should include screening to aid recognition of high-risk families, who become the focus in a family-centered model of care. However, replication of this trial is needed before we can confidently call for the inherent place of our model in palliative care.

Our finding of potential harm to hostile families highlights the need to differentiate between them and intermediate or sullen types. We will revise our guidelines to reflect a respectful response to a family’s naturalistic solution of distance to substantial ambivalence about relationships. When conflict seems inevitable, the benefits of bringing family members together for a meeting may be negligible. Intermediate and sullen family types will obviously be the principal targets of family focused grief therapy. The willingness of families to embrace treatment serves as a guide to those more likely to benefit.

Conclusions

We believe that this is the first formal study of psychotherapy with a high-risk group of families facing the death of a relative. Our data indicate that family focused grief therapy reduces distress and protects partially against pathological grief. Families with a sullen or intermediate class of functioning are particularly suitable for preventive intervention with family focused grief therapy, while members of hostile families may be better helped individually, given their propensity to interact in a conflictual manner. We hope that other researchers will join in ascertaining optimal models of treatment for at-risk families in the context of palliative care.

1. Kato PM, Mann T: A synthesis of psychological interventions for the bereaved. Clin Psychol Rev 1999; 19:275–296Google Scholar

2. Jordan J, Neimeyer R: Does grief counseling work? Death Stud 2003; 27:765–786Google Scholar

3. Harding R, Higginson I: What is the best way to help caregivers in cancer and palliative care? a systematic literature review of interventions and their effectiveness. Palliat Med 2003; 17:63–74Google Scholar

4. Allumbaugh DL, Hoyt W: Effectiveness of grief therapy: a meta-analysis. J Couns Psychol 1999; 46:370–380Google Scholar

5. Higginson IJ, Finlay IG, Goodwin DM, Hood K, Edwards AG, Cook A, Douglas HR, Normand CE: Is there evidence that palliative care teams alter end-of-life experiences of patients and their caregivers? J Pain Symptom Manage 2003; 25:150–168Google Scholar

6. Schut H, Stroebe M, Van Den Bout J, Terheggen M: The efficacy of bereavement interventions: who benefits?, in Handbook of Bereavement Research. Edited by Stroebe MS, Hansson RO, Stroebe W, Schut H. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 2001, pp 705–738Google Scholar

7. Moos RH, Moos BS: Family Environment Scale Manual. Stanford, Calif, Consulting Psychologists Press, 1981Google Scholar

8. Kissane DW, Bloch S, Burns WI, McKenzie DP, Posterino M: Psychological morbidity in the families of patients with cancer. Psychooncology 1994; 3:47–56Google Scholar

9. Kissane DW, Bloch S, Burns WI, Patrick JD, Wallace CS, McKenzie DP: Perceptions of family functioning and cancer. Psychooncology 1994; 3:259–269Google Scholar

10. Kissane DW, Bloch S, Dowe DL, Snyder RD, Onghena P, McKenzie DP, Wallace CS: The Melbourne Family Grief Study, I: perceptions of family functioning in bereavement. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:650–658Google Scholar

11. Kissane DW, Bloch S, Onghena P, McKenzie DP, Snyder RD, Dowe DL: The Melbourne Family Grief Study, II: psychosocial morbidity and grief in bereaved families. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:659–666Google Scholar

12. Kissane DW, Bloch S, McKenzie M, McDowall AC, Nitzan R: Family grief therapy: a preliminary account of a new model to promote healthy family functioning during palliative care and bereavement. Psychooncology 1998; 7:14–25Google Scholar

13. Kissane DW, McKenzie M, McKenzie DP, Forbes A, O’Neill I, Bloch S: Psychosocial morbidity associated with patterns of family functioning in palliative care: baseline data from the Family Focused Grief Therapy controlled trial. Palliat Med 2003; 17:527–537Google Scholar

14. Edwards B, Clarke V: The validity of the Family Relationships Index as a screening tool for psychological risk in families of cancer patients. Psychooncology 2005; 14:546–554Google Scholar

15. Kissane DW, Bloch S: Family Focused Grief Therapy: A Model of Family-Centred Care During Palliative Care and Bereavement. Buckingham, UK, Open University Press, 2002Google Scholar

16. Chan EK, O’Neill I, McKenzie M, Love A, Kissane DW: What works for therapists conducting family meetings: treatment integrity in family-focused grief therapy during palliative care and bereavement. J Pain Symptom Manage 2004; 27:502–512Google Scholar

17. Synder W, McCollum EE: Their home is their castle: learning to do in-home family therapy. Fam Process 1999; 38:229–242Google Scholar

18. Erdfelder E, Faul F: GPOWER: a general power analysis program. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput 1996; 28:1–11Google Scholar

19. Cohen J: A power primer. Psychol Bull 1992; 112:155–159Google Scholar

20. Bird KD, Hall W: Statistical power in psychiatric research. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 1986; 20:189–200Google Scholar

21. Moos RH: Conceptual and empirical approaches to developing family-based assessment procedures: resolving the case of the Family Environment Scale. Fam Process 1990; 29:199–208Google Scholar

22. Epstein N, Baldwin L, Bishop D: The McMaster Family Assessment Device. J Marital Fam Ther 1983; 9:171–180Google Scholar

23. Miller IW, Epstein NB, Bishop DS, Keitner GI: The McMaster Family Assessment Device: reliability and validity. J Marital Fam Ther 1985; 11:345–356Google Scholar

24. Derogatis LR, Spencer PM: The Brief Symptom Inventory: Administration, Scoring and Procedure Manual-I. Baltimore, Clinical Psychometric Research, 1982Google Scholar

25. Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N: The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med 1983; 13:595–605Google Scholar

26. Beck A, Beck R: Screening depressed patients in family practice: a rapid technique. Postgrad Med 1972; 52:81–85Google Scholar

27. Beck A, Steer R, Garbin M: Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev 1988; 8:77–100Google Scholar

28. Cooper P, Osborn M, Gath D, Feggetter G: Evaluation of a modified self-report measure of social adjustment. Br J Psychiatry 1982; 141:68–75Google Scholar

29. Byrne GJA, Raphael B: A longitudinal study of bereavement phenomena in recently widowed elderly men. Psychol Med 1994; 24:411–421Google Scholar

30. Burnett P, Middleton W, Raphael B, Dunne M, Moylan A, Martinek N: Concepts of normal bereavement. J Trauma Stress 1994; 7:123–128Google Scholar

31. Bland JM, Altman DG: Survival probabilities (the Kaplan-Meier method). BMJ 1998; 317:1572Google Scholar

32. Rao JNK, Thomas DR: Chi-square tests for contingency tables, in Analysis of Complex Surveys. Edited by Skinner CJ, Holt D, Smith TMF. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1989, pp 89–114Google Scholar

33. Liang KY, Zeger SL: Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika 1986; 73:13–22Google Scholar

34. White H: Maximum likelihood estimation of misspecified models. Econometrica 1982; 50:1–25Google Scholar

35. Lichtenthal WG, Cruess DG, Prigerson HG: A case for establishing complicated grief as a distinct mental disorder in DSM-V. Clin Psychol Rev 2004; 24:637–662Google Scholar

36. Miller IW, Ryan CE, Keitner GI, Bishop DS, Epstein NB: “Factor analyses of the family assessment device,” by Ridenour, Daley, & Reich. Fam Process 2000; 39:141–144Google Scholar

37. Ridenour TY, Daley JG, Reich A: Further evidence that the Family Assessment Device should be reorganized: response to Miller and colleagues. Fam Process 2000; 39:375–380Google Scholar

38. Kissane DW: Grief and the family, in The Family in Clinical Psychiatry. Edited by Bloch JHS, Harari E, Szmukler G. Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press, 1994, pp 71–91Google Scholar

39. Marriott A, Donaldson C, Tarrier N, Burns A: Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioural family intervention in reducing the burden of care in carers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Br J Psychiatry 2000; 176:557–562Google Scholar

40. Ringdal GI, Jordhoy MS, Ringdal K, Kaasa S: The first year of grief and bereavement in close family members to individuals who have died of cancer. Palliat Med 2001; 15:91–105Google Scholar

41. Kelly B, Edwards P, Synott R, Neil C, Baillie R, Battistutta D: Predictors of bereavement outcome for family carers of cancer patients. Psychooncology 1999; 8:237–249Google Scholar

42. Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry Committee on the Family: Global Assessment of Relational Functioning scale (GARF), I: background and rationale. Fam Process 1996; 35:155–172Google Scholar

43. Neimeyer RA: Grief therapy and research as essential tensions: prescriptions for a progressive partnership. Death Stud 2000; 24:603–610Google Scholar