What Happened to Lithium? Antidepressant Augmentation in Clinical Settings

Abstract

Objective: Antidepressant augmentation is recommended when patients do not respond to antidepressant monotherapy. However, little is know about antidepressant augmentation in clinical settings and whether these practices reflect the research evidence. Method: The authors identified 244,859 patients in Veterans Administration mental health settings with a diagnosis of depression and an antidepressant prescription during fiscal year 2002. Patients with schizophrenia, dementia, or bipolar I disorder were excluded. The authors examined the prevalence and characteristics of antidepressant augmentation during the year, defined as receiving an antidepressant and an augmenting agent (lithium, second-generation antipsychotics, combinations of antidepressants, anticonvulsants, or “other”) for ≥60 consecutive days in specified doses for those without other clinical indications. Mixed-effect models were used to examine predictors of augmentation. Results: Some patients (22%) received an augmenting agent. The most commonly used agents were a second antidepressant (11%) and a second-generation antipsychotic (7%). Only 0.5% of the patients received lithium. Whites, younger patients, and those with a prior hospitalization were more likely to receive augmentation. African Americans were more likely to receive antipsychotic augmentation; whites were more likely to receive lithium. Conclusions: Antidepressant augmentation is common in clinical settings. Although lithium currently has the most research support, antipsychotic medications and a second antidepressant are the most widely used augmenting agents. Many augmenting agents are used across clinical and demographic groups. Research is needed on the relative effectiveness of these agents, along with efforts to promote the use of agents with the greatest level of research support.

Depression is a common, treatable disorder. However, only 40%–60% of depressed patients respond to a first antidepressant monotherapy trial with a 50% or greater reduction in depressive symptoms (1) . Only 20%–30% experience a full remission of their depressive symptoms during the first antidepressant trial (2 , 3) .

Practice guidelines about depression often recommend further treatment interventions when patients fail to respond to two or more trials of antidepressant monotherapy, and many clinicians and researchers recommend further treatment interventions when patients fail to achieve full remission (3 – 5) . Antidepressant augmentation, or the addition of a second agent to antidepressant therapy to increase its effectiveness in reducing the core symptoms of depression, is one of the most commonly recommended interventions. Treatment guidelines most often mention lithium, thyroid supplements, a second “add-on” antidepressant, second-generation antipsychotic medications, anticonvulsant medications, stimulants, and buspirone as potentially helpful augmenting agents (4 , 6 , 7) .

However, many of these agents have only limited research evidence for effectiveness (3) . Lithium is generally acknowledged to have the strongest research support; there are a number of randomized, controlled trials indicating that adding lithium to antidepressants reduces symptoms among patients with unipolar depression and an incomplete response (7 – 9) . Most important for patients with refractory depression, lithium has also been reported to have a specific antisuicide effect for patients with mood disorders (10 , 11) .

Most of the other medications that are suggested as augmenting agents have relatively weak evidence for effectiveness. For patients with unipolar depression, the use of anticonvulsants and stimulants is supported mostly by open-label studies, as is the use of second-generation antipsychotic medications for patients with nonpsychotic depression. We discovered one small controlled trial reporting positive results when lamotrigine, an anticonvulsant, was added to fluoxetine, an antidepressant (12) , and one small controlled study that reported positive results when olanzapine, an antipsychotic, was added to fluoxetine (13) . However, at least two randomized, controlled trials also reported negative results for antipsychotic augmentation (14 , 15) . Most randomized, controlled trials examining the effectiveness of combination antidepressant strategies have examined tricyclic agents in combination with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (16) , with just one or two trials examining combinations of newer antidepressants (17) .

Although many depression treatment guidelines comment on the strength of the research supporting lithium’s effectiveness as an augmenting agent, guidelines vary on whether they suggest a specific sequence of augmentation trials, the order in which they suggest the augmentation trials should proceed, and how strongly they recommend a trial of lithium (4 , 5) . Clinical and research leaders have noted a paucity of studies that definitively guide the sequence in which augmentation strategies should be tried and the groups of patients for whom specific strategies might be most helpful (3 , 18) .

Currently, little is known about what augmentation strategies are used in clinical settings or the subgroups of patients who are receiving augmentation. In this study, we describe the use of augmentation strategies among depressed patients treated in Veterans Administration (VA) mental health settings during fiscal year 2002. We describe the prevalence of specific augmentation strategies, including preferred combinations of antidepressants with augmenting agents. We also describe patient factors that are associated with receiving augmentation generally and patient factors that are associated with receiving specific augmenting agents, including lithium.

Method

Data on patients’ diagnoses, demographic characteristics, medications, and health services use were obtained from the VA’s National Registry for Depression. The registry is maintained by the Serious Mental Illness Treatment, Research, and Evaluation Center, located in Ann Arbor, Mich. The institutional review board of the VA Ann Arbor Health System approved the study.

Study Population

Patients were included in the study if they had received a diagnosis of depression in specialty mental health settings and an antidepressant medication during fiscal year 2002 (Oct. 1, 2001, through Sept. 30, 2002). We identified patients with diagnoses of depression using the following ICD-9 codes: 296.2x, 296.3x, 296.90, 296.99, 300.4, 311, 293.83, 301.12, 309.0, and 309.1. The patients who received ICD-9 codes indicating diagnoses of bipolar I disorder, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or dementia during the study year were excluded. Mental health settings were defined with VA clinic visits and bed section codes. The final sample size was 244,859 patients.

Study Measures

Patient demographic characteristics

With data from the National Registry for Depression, the patients were categorized into three age groups based on their age at the beginning of fiscal year 2002: 1) ages <45 years, 2) ages 45–64 years, and 3) ages ≥65 years. The patients’ race/ethnicity was categorized as African American, Asian/American Indian, white, Hispanic, or “unknown.”

Antidepressant augmentation

We examined whether the patients received any of five different antidepressant augmentation strategies during fiscal year 2002, including augmentation with the following medications: 1) lithium, 2) second-generation antipsychotics, 3) combination antidepressant treatment, 4) anticonvulsant mood stabilizers other than gabapentin, and 5) “other agents,” such as liothyronine/T 3 , stimulants, and buspirone.

The antidepressants considered in this study included amitriptyline, desipramine, doxepin, imipramine, clomipramine, nortriptyline, phenelzine, tranylcypromine, bupropion, citalopram, fluoxetine, nefazodone, paroxetine, sertraline, trazodone, venlafaxine, mirtazapine, fluvoxamine, escitalopram, amoxapine, isocarboxazid, maprotiline, protriptyline, and trimipramine. The second-generation antipsychotics considered included clozapine, ziprasidone, risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, and aripiprazole. The anticonvulsants considered included carbamazepine, oxycarbamazepine, divalproex/valproic acid, lamotrigine, and topiramate. (We did not include gabapentin in the anticonvulsant augmentation group because it is prescribed for a number of medical conditions and is usually not considered to be an augmenting agent for unipolar depression.) Finally, the stimulant medications considered in the study included dextroamphetamine, methylphenidate, and amphetamine.

We took several steps to distinguish depressed patients whose providers were using these medications to augment antidepressants rather than simply switching medications or treating isolated symptoms, such as insomnia or co-occurring medical or psychiatric conditions.

First, we considered patients to have received antidepressant augmentation only if they had overlapped taking both their augmenting agent and their antidepressant for ≥60 consecutive days, making simple switching and cross-tapering less likely. Second, we considered antidepressants to be used in combination therapy only if both antidepressants were prescribed in doses that are commonly used to treat core depressive symptoms rather than doses commonly used to treat isolated symptoms, such as insomnia. Thus, trazodone, mirtazapine, and amitriptyline were considered to be used as augmenting agents rather than hypnotics, but only if the doses were ≥300 mg/day, ≥45 mg/day, or >50 mg/day, respectively.

Finally, we considered medications to be used as augmenting agents only if the patients did not have co-occurring medical or psychiatric disorders for which these agents were also indicated. Thus, the patients were considered to be receiving anticonvulsants or liothyronine/T 3 as augmenting agents only if they did not have concurrent seizure disorders or concurrent hypothyroidism, respectively. The patients were considered to have received augmentation with a second-generation antipsychotic medication only if they did not have a diagnosis of major depression with psychosis. (The patients who had diagnoses of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, and dementia, for which antipsychotics are commonly prescribed, were excluded from the original study sample.)

We did not attempt to distinguish depressed patients who had a second antidepressant agent added to their first antidepressant for the treatment of sexual dysfunction or for pain because these side effects/symptoms are not reliably associated with ICD-9 codes or differential antidepressant dosing.

Further description of augmenting strategies

Among patients receiving lithium, we calculated the mean prescribed dose by first calculating the average dose prescribed to each patient during the year and then averaging the mean lithium dose across patients. We excluded liquid preparations of lithium from these analyses because of difficulties in calculating doses, resulting in the exclusion of five patients from the dosage analyses. We used the patients’ first augmentation episode of the year when describing the frequency of specific combinations of antidepressants or combinations of antidepressants with antipsychotics.

Covariates for medical and psychiatric disorders

We used a modified version of the Charlson Co-Morbidity Index as a measure of medical comorbidity (19) . The Charlson Co-Morbidity Index, in this instance, was based on the presence or absence of each of 19 medical conditions in administrative data during fiscal year 2002. Dummy variables were constructed for three categories of scores: 1) 0 (indicating that the patients did not have any of these medical conditions), 2) Charlson Co-Morbidity Index score of 1 or 2, or 3) a score of 3 or more.

As a measure of psychiatric comorbidity, we constructed three dichotomous variables indicating whether depressed patients also received a diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), other anxiety disorders, or substance abuse during fiscal year 2002. As a measure of psychiatric severity, we constructed a dichotomous indicator for whether patients had had a psychiatric hospitalization in the fiscal year before the study (2001).

Data Analysis

Patient characteristics and the frequency of specific augmentation strategies were described with means, SDs, and frequencies. For the 244,855 patients with complete data, we used a generalized linear mixed-effect model (GLIMMIX in SAS 8.02, SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.) with the LOGIT link function to examine the relationship between the dichotomous dependent variables “received any augmentation strategy” and independent patient-level variables entered simultaneously, including age group, sex, racial/ethnic group, Charlson Co-Morbidity Index score category, psychiatric hospitalization during the previous year, the presence of a concurrent PTSD diagnosis, the presence of another anxiety disorder, and the presence of a concurrent substance abuse disorder. Unlike logistic regression models, mixed-effect models allowed us to account for the clustering of patients within VA facilities.

Among the 53,807 patients who received augmentation strategies in fiscal year 2002, we conducted five separate mixed-effect models. Each analysis separately examined the influence of the patient factors we outlined and the likelihood of receiving one of the five specific augmenting agents (lithium, a second-generation antipsychotic, a combination of antidepressants, an anticonvulsant, or “other”).

Results

The majority of the patients in the sample (N=220,502, 90%) were men, reflecting the VA population; 54,643 (22%) were older than 65 years of age. Approximately 13,687 (6%) of the depressed patients had had a psychiatric hospitalization during the prior fiscal year. Comorbid anxiety and substance abuse disorders were common, with 68,197 (28%), 59,028 (24%), and 51,774 (21%) patients also having diagnoses of PTSD, another anxiety disorder, or substance abuse, respectively, during the study year.

Use of Augmentation Strategies

Approximately 53,807 (22%) of the depressed VA patients treated in mental health settings received antidepressant augmentation, with approximately 10,542 (4%) receiving more than one augmenting agent during the year. The most popular augmenting agents were a second antidepressant and a second-generation antipsychotic, received by 26,739 (11%) and 17,797 (7%) patients, respectively. Approximately 9,053 patients (4%) received augmentation with anticonvulsants, and 11,054 (5%) received other augmenting agents. Surprisingly, only 1,106 patients (0.5%) received augmentation with lithium.

Table 1 shows the nine most frequently used antidepressant combinations and the 10 most frequently used antidepressant-antipsychotic combinations. Bupropion and mirtazapine were the most frequently appearing antidepressants in combined antidepressant augmentation strategies. Bupropion appeared in 20,279 (38%) of all antidepressant-antidepressant combinations, and mirtazapine appeared in 5,159 (19%). Risperidone and olanzapine were the most frequently appearing antipsychotic agents in antidepressant-antipsychotic combinations. Risperidone appeared in 6,699 (38%) of all antidepressant-antidepressant combinations, and olanzapine appeared in 5,657 (32%). Among patients receiving lithium augmentation, the mean dose of lithium was 758 mg/day.

Characteristics of Patients Receiving Antidepressant Augmentation

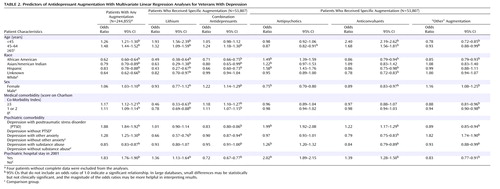

Several patient-level factors were associated with the likelihood of receiving “any” antidepressant augmentation and with the likelihood of receiving one augmentation strategy versus another. Table 2 includes the odds ratios for receiving “any” drug augmentation during fiscal year 2002 among all 244,855 depressed patients and also includes the odds ratios for receiving each of five specific augmentation strategies among the 53,807 patients receiving specific augmentation.

As noted in Table 2 , both clinical and demographic factors were associated with receiving some augmentation strategy during the year and with receiving specific augmenting agents. The clinical factors associated with a greater likelihood of receiving any augmentation strategy during the year included having a previous psychiatric hospitalization (odds ratio=1.83) and comorbidities of PTSD (odds ratio=1.88) and other anxiety disorders (odds ratio=1.28). Demographic factors associated with receiving some augmentation strategy were a younger age and white race/ethnicity.

Among patients receiving augmentation, clinical and demographic factors were also associated with the specific augmenting agents used. The patients with previous hospitalizations were more likely to receive lithium (odds ratio=1.36), antipsychotics (odds ratio=2.02), or anticonvulsants (odds ratio=1.39) and less likely to receive a second antidepressant (odds ratio=0.72) than other agents. The patients with comorbid PTSD were more likely to receive antipsychotic augmentation (odds ratio=1.99). African American and Hispanic patients were more likely to receive antipsychotic augmentation than whites (odds ratios=1.49 and 1.58, respectively) but were less likely to receive lithium (odds ratios=0.49 and 0.43, respectively).

Discussion

Antidepressant augmentation is common in clinical settings, suggesting that providers often use augmenting agents when patients fail to respond to antidepressant monotherapy. In our study, approximately 22% of depressed patients receiving antidepressants during the study year also received an augmenting agent, a figure that is consistent with the estimated percentages of patients failing to respond to two or more trials of antidepressant monotherapy (4) .

A wide variety of augmenting agents appear to be used in clinical practice. The most popular augmenting agents are a second antidepressant or a second-generation antipsychotic, agents for which there is currently only limited research evidence (13 – 15) . Most studies that have examined combination antidepressant strategies have examined the use of SSRIs in combination with tricyclic agents (16) , with only one or two controlled trials examining combinations of newer antidepressants, the most commonly used strategy in this study (17) . The use of second-generation antipsychotics in nonpsychotic depression is supported by several open-label studies, but only one controlled study, to our knowledge (13) . At least two controlled trial also reported negative results (14 , 15) .

Although lithium’s effectiveness as an augmenting agent is supported by multiple randomized, controlled trials, and lithium has also been reported to have a specific antisuicide effect (20 , 21) , it is used relatively rarely in clinical settings (by just 0.5% of depressed patients). Previous studies that have surveyed physicians about their preferred “next step” strategies when patients fail to respond to antidepressant monotherapy have found that relatively few physicians report that they would try lithium augmentation (22) . These survey findings and our observational data suggest that lithium augmentation may be a vanishing practice. The reasons for the low use of lithium are unclear but may include concerns about safety, convenience, tolerability, or stigma—and potentially—diminished efficacy when patients are given prescriptions for SSRIs instead of tricyclic agents (23) . A relative lack of advertising and visibility may also contribute to low use of lithium.

Unlike more popular augmentation strategies, lithium requires regular laboratory monitoring of medication blood levels, with therapeutic doses sometimes being close to toxicity. All augmenting agents have side effects, with popular second-generation antipsychotics potentially promoting weight gain and metabolic abnormalities over the long term (24) . However, several of lithium’s side effects may appear shortly after treatment initiation, including gastrointestinal distress, polyuria, and tremor, potentially prompting earlier discontinuation. In the longer term, lithium may also cause renal impairment (25) . The marked shift from using tricyclic agents to using SSRIs may also have resulted in decreased efficacy and potentially decreased use of lithium augmentation, with at least one randomized, controlled trail noting that the combination of lithium and fluvoxamine was less efficacious than the combination of lithium and imipramine (23) . Finally, unlike lithium, the newer antidepressants and antipsychotic agents are backed by large advertising budgets and are the subjects of numerous recent articles. Providers may have difficulty ascertaining the level of research evidence for alternative augmentation strategies and may be more influenced by newer than by older studies when making prescribing decisions.

We note that the prevalence of antidepressant augmentation and the use of specific augmenting agents differed markedly across both clinical and demographic subgroups. As might be expected, the patients with more severe depressive illnesses (as inferred by a previous psychiatric hospitalization) were more likely to receive at least one augmenting agent, as were patients with comorbid PTSD or other anxiety disorders. These patients may have had more severe disorders and been less likely to respond to antidepressant monotherapy. Among patients receiving augmentation, patients with past psychiatric hospitalizations were more likely to receive lithium, anticonvulsants, and antipsychotics and less likely to receive combinations of antidepressants. Lithium, anticonvulsants, and antipsychotics may be considered more appropriate for patients with severe illnesses, whereas the addition of a second antidepressant agent may be viewed as producing fewer side effects and as being appropriate for patients with less severe impairment.

In this study, older patients were less likely to receive antidepressant augmentation than younger patients, perhaps because of concerns about adding medications to these patients’ more complicated medical regimens or because of older patients’ greater susceptibility to side effects.

The reasons for the lower rates of augmentation among African American and Hispanic patients than among white patients are less clear, given little available evidence for different rates of response to antidepressant monotherapy among these subgroups or different degrees of susceptibility to the side effects of augmenting agents. However, differential use may result from differences in provider-patient communications (26) or from patient treatment preferences. In surveys, African Americans are less likely to report that antidepressants are an acceptable treatment option, and they are less likely to accept antidepressant medications when they are recommended by their providers (27 , 28) . It is possible that the relative reluctance of African Americans to accept antidepressants may extend to agents that are offered later to augment treatment response.

We note that among patients who did receive antidepressant augmentation, African Americans and Hispanics were less likely to receive lithium but were more likely to receive augmentation with antipsychotics. Previous studies have suggested that providers may use antipsychotic medications differentially across racial groups for other psychiatric conditions (29 , 30) .

Our finding of the widespread use of many augmenting agents, particularly second add-on antidepressants or second-generation antipsychotics, demonstrates the importance of trials such as the ongoing Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial. STAR*D is currently examining the effectiveness of several augmenting strategies, including a second antidepressant. A planned follow-up to the STAR*D trial may examine the option of adding an antipsychotic as an augmenting agent. Clearly, there is an urgent need for randomized, controlled trials that rigorously examine the relative effectiveness of these widely used agents in comparison with other agents, both across the depressed population and within important patient subgroups.

Limitations

This study was conducted in only one large national health care system—that of the VA. Although the VA has the nation’s largest health care system, it is possible that the prevalence of antidepressant augmentation overall, and of lithium augmentation in particular, may differ from that seen in other health systems. We also note that administrative pharmacy data were used in this study. Despite our best efforts, we likely were unable to perfectly distinguish all patients who were receiving antidepressant augmentation from those who were switching medications or receiving the specified agents for other clinical indications. For example, bupropion might have been added to a first antidepressant to treat sexual side effects rather than to augment antidepressant response, resulting in higher estimates of combined antidepressant augmentation than might be obtained from chart reviews. However, we made many conservative assumptions when we considered whether a specific medication was added for augmentation purposes (requiring a ≥60 day overlap of the antidepressant and the augmenting agent, specifying dosing criteria for antidepressants, and requiring the absence of many other common clinical indications), making systematic overestimation of augmentation less likely. We note that our overall estimate of augmentation was in line with previous estimates of the percentages of depressed patients failing to improve with monotherapy and that our observation about the limited use of lithium (0.5%) compared to other augmenting agents would be unaffected by modest changes in these estimates.

In summary, antidepressant augmentation is common in clinical settings. Lithium rarely appears to be used as an augmenting agent, whereas antipsychotic medications and second antidepressants are widely used. The literature supporting the effectiveness of the latter two strategies is sparse. Many augmenting agents are used differentially across patient subgroups. There is an urgent need for additional randomized, controlled trials that examine the relative effectiveness of the various augmenting agents across the depressed patient population and within important demographic and clinical subgroups. Efforts must also be made to promote use of the agents that have the greatest evidence for efficacy both currently and as the research literature evolves.

1. Williams JW Jr, Mulrow CD, Chiquette E, Noel PH, Aguilar C, Cornell J: A systematic review of newer pharmacotherapies for depression in adults: evidence report summary. Ann Intern Med 2000; 132:743–756Google Scholar

2. Fava M, Davidson KG: Definition and epidemiology of treatment-resistant depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1996; 19:179–200Google Scholar

3. Fava M, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Nierenberg AA, Thase ME, Sackeim HA, Quitkin FM, Wisniewski S, Lavori PW, Rosenbaum JF, Kupfer DJ: Background and rationale for the sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression (STAR*D) study. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2003; 26:457–494Google Scholar

4. American Psychiatric Association: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder (revision). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2000Google Scholar

5. Trivedi MH, Shon S, Crismon ML, Key T: Texas Implementation of Medication Algorithms (TIMA): Guidelines for Treating Major Depressive Disorder: TIMA Physician Procedure Manual. Sept 2000. www.dshs.state.tx.us/mhprograms/timaMDDman.pdfGoogle Scholar

6. Dording CM: Antidepressant augmentation and combinations. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2000; 23:743–755Google Scholar

7. Shelton RC: The use of antidepressants in novel combination therapies. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64(suppl 2):14–18Google Scholar

8. Bauer M, Adli M, Baethge C, Berghofer A, Sasse J, Heinz A, Bschor T: Lithium augmentation therapy in refractory depression: clinical evidence and neurobiological mechanisms. Can J Psychiatry 2003; 48:440–448Google Scholar

9. Bauer M, Dopfmer S: Lithium augmentation in treatment-resistant depression: meta-analysis of placebo-controlled studies. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1999; 19:427–434Google Scholar

10. Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, Hennen J: Lithium treatment and suicide risk in major affective disorders: update and new findings. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64:44–52Google Scholar

11. American Psychiatric Association: Practice Guideline for the Assessment and Treatment of Patients With Suicidal Behaviors. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160:1–60; erratum, 161:776Google Scholar

12. Barbosa L, Berk M, Vorster M: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of augmentation with lamotrigine or placebo in patients concomitantly treated with fluoxetine for resistant major depressive episodes. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64:403–407Google Scholar

13. Shelton RC, Tollefson GD, Tohen M, Stahl S, Gannon KS, Jacobs TG, Buras WR, Bymaster FP, Zhang W, Spencer KA, Feldman PD, Meltzer HY: A novel augmentation strategy for treating resistant major depression. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:131–134Google Scholar

14. Shelton RC: The combination of olanzapine and fluoxetine in mood disorders. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2003; 4:1175–1183Google Scholar

15. Dube S, Paul S, Sanger T, Van Campen L, Corya S, Tollefson G: Olanzapine-fluoxetine combination in treatment resistant depression (abstract). Eur Psychiatry 2002; 17(suppl 1):98Google Scholar

16. Nelson JC, Mazure CM, Jatlow PI, Bowers MB Jr, Price LH: Combining norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake inhibition mechanisms for treatment of depression: a double-blind, randomized study. Biol Psychiatry 2004; 55:296–300Google Scholar

17. Carpenter LL , Yasmin S, Price LH: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of antidepressant augmentation with mirtazapine. Biol Psychiatry 2002; 51:183–188Google Scholar

18. Stimpson N, Agrawal N, Lewis G: Randomised controlled trials investigating pharmacological and psychological interventions for treatment-refractory depression: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry 2002; 181:284–294Google Scholar

19. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR: A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987; 40:373–383Google Scholar

20. Bauer M, Adli M, Baethge C, Berghofer A, Sasse J, Heinz A, Bschor T: Lithium augmentation therapy in refractory depression: clinical evidence and neurobiological mechanisms. Can J Psychiatry 2003; 48:440–448Google Scholar

21. Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, Hennen J: Treating the suicidal patient with bipolar disorder: reducing suicide risk with lithium. Ann NY Acad Sci 2001; 932:24–43Google Scholar

22. Fredman SJ, Fava M, Kienke AS, White CN, Nierenberg AA, Rosenbaum JF: Partial response, nonresponse, and relapse with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in major depression: a survey of current “next-step” practices. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61:403–408Google Scholar

23. Birkenhager TK, van den Broek WW, Mulder PG, Bruijn JA, Moleman P: Comparison of two-phase treatment with imipramine or fluvoxamine, both followed by lithium addition, in inpatients with major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:2060–2065Google Scholar

24. American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, North American Association for the Study of Obesity: Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Obes Res 2004; 12:362–368Google Scholar

25. Moore D, Jefferson J: Handbook of Medical Psychiatry, 2nd Ed. Philadelphia, Elsevier/Mosby, 2004Google Scholar

26. Balsa AI, Seiler N, McGuire TG, Bloche MG: Clinical uncertainty and healthcare disparities. Am J Law Med 2003; 29:203–219Google Scholar

27. Miranda J, Cooper LA: Disparities in care for depression among primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med 2004; 19:120–126Google Scholar

28. Cooper LA, Gonzales JJ, Gallo JJ, Rost KM, Meredith LS, Rubenstein LV, Wang NY, Ford DE: The acceptability of treatment for depression among African-American, Hispanic, and white primary care patients. Med Care 2003; 41:479–489Google Scholar

29. Fleck DE, Hendricks WL, DelBello MP, Strakowski SM: Differential prescription of maintenance antipsychotics to African American and white patients with new-onset bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63:658–664Google Scholar

30. Copeland LA, Zeber JE, Valenstein M, Blow FC: Racial disparity in the use of atypical antipsychotic medications among veterans. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:1817–1822Google Scholar