Aripiprazole in the Treatment of Patients With Borderline Personality Disorder: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study

Abstract

Objective: Aripiprazole is a relatively new atypical antipsychotic agent that has been successfully employed in therapy for schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders. A few neuroleptics have been used in therapy for patients with borderline personality disorder, which is associated with severe psychopathological symptoms. Aripiprazole, however, has not yet been tested for this disorder, and the goal of this study was to determine whether aripiprazole is effective in the treatment of several domains of symptoms of borderline personality disorder. Method: Subjects meeting criteria for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders for borderline personality disorder (43 women and 9 men) were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to 15 mg/day of aripiprazole (N=26) or placebo (N=26) for 8 weeks. Primary outcome measures were changes in scores on the symptom checklist (SCL-90-R), the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A), and the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory and were assessed weekly. Side effects and self-injury were assessed with a nonvalidated questionnaire. Results: According to the intent-to-treat principle, significant changes in scores on most scales of the SCL-90-R, the HAM-D, the HAM-A, and all scales of the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory were observed in the subjects treated with aripiprazole after 8 weeks. Self-injury occurred in the groups. The reported side effects were headache, insomnia, nausea, numbness, constipation, and anxiety. Conclusions: Aripiprazole appears to be a safe and effective agent in the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder.

Aripiprazole is an atypical antipsychotic agent with a novel mechanism of action that has been successfully employed in medication therapy for schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders (1 , 2) . It also has Food and Drug Administration approval for treatment of the manic and mixed states of bipolar disorder. A partial agonist at dopamine D 2 and serotonin 5-HT 1A receptors and an antagonist at 5-HT 2A receptors, it is thought to have a stabilizing effect on the dopamine-serotonin system that is advantageous because it is associated with fewer adverse effects (3 – 9) , although some of them are reported to be severe (10 , 11) .

The characteristics that make aripiprazole interesting in the treatment of schizophrenia (12) and bipolar mania (13) could also prove to have a positive influence on the treatment of other psychiatric illnesses (14 – 16) . One illness that is difficult to treat is borderline personality disorder (17 – 22) , which is characterized by a pervasive pattern of severe psychopathological symptoms with instability of affect regulation, impulse control, and aggression (23 – 29) . Dysfunctions in the serotoninergic and dopaminergic systems have been demonstrated in—and considered as possible causes for—symptoms associated with the disorder (30 – 33) . Several studies on the use of traditional (34) and atypical antipsychotic agents in patients with borderline personality disorder (35 – 36) have shown a positive effect on individual symptoms (34 , 37–41) . However, we are not aware of any study evaluating aripiprazole in the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder. In the present double-blind, placebo-controlled study, the influence of aripiprazole on the multifaceted psychopathological symptoms and aggression of patients with borderline personality disorder was investigated.

Method

Subjects

Fifty-seven subjects ages 16 and older who were disturbed by moodiness, distrustfulness, impulsivity, and painful, difficult relationships were recruited through advertisements. They were screened on the telephone to assess whether they met DSM-IV criteria for borderline personality disorder. A general medical history was also taken.

The subjects participated in face-to-face interviews. Possible side effects were fully explained, and written informed consent was obtained. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (SCID II) were then carried out. Subjects were included if they met criteria for borderline personality disorder. They then underwent physical and laboratory examinations.

Criteria for exclusion (N=5) were schizophrenia, current use of aripiprazole or another psychotropic medication, current psychotherapy, pregnancy (including planned pregnancy or sexual activity without contraception), current suicidal ideation, or current severe somatic illness.

Assessment

The symptom checklist (SCL-90-R) is a self-report inventory that measures physical and mental symptoms during the previous week on nine scales: somatization, obsessive-compulsiveness, insecurity in social contacts, depression, anxiety, aggressive/hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid thinking, and psychoticism. The Global Severity Index (GSI) measures the person’s basic mental stress on a 5-step Likert scale. Transformation of the raw values to T values, which take sociodemographic factors into consideration, permits classification of individual cases. T values of 60 or more are regarded as mildly increased, of 70 or more as greatly increased, and of 75 or more as very greatly increased. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) ranges from r=0.75 to r=0.87 (42) .

The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) (43) is a validated scale that quantifies the severity of depressive symptoms (Cronbach’s alpha between 0.52 and 0.95; retest correlation between 0.65 and 0.81), including depressed mood, vegetative, and cognitive symptoms of depression and comorbid anxiety symptoms, and rates them on either a 5-point (0–4) or a 3-point (0–2) Likert scale. It provides ratings on current DSM-IV symptoms of depression, with the exception of hypersomnia, increased appetite, and concentration/indecision.

The Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) (44) is a validated scale that quantifies the severity of anxiety, regardless of the etiology (Cronbach’s alpha between 0.74 and 0.96; retest correlation between 0.64 and 0.96) on a 5-point (0–4) Likert scale covering 14 psychological and physical symptoms.

The State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory measures anger and the expression of anger (women: Cronbach’s alpha=0.75; retest correlation after 8 weeks=0.70–0.76) on five scales—state anger: a subjective state of anger at the time of measurement; trait anger: a readiness to react with anger; anger in: a tendency to repress anger; anger out: a tendency to express anger; and anger control (21 , 22 , 45) .

The necessary group size was calculated for a type I error rate of 5% (z 1 =1.96) and a power analysis of 80% (z 2 =0.84) based on the means (m 1 =57.2 and m 2 =67.8) and SDs (s 1 =14.3 and s 2 =12.9) for the psychoticism scale of the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short-Form Health Survey, which were obtained from a small pilot study. The formula is the number per group as follows: [(z 1 +z 2 ) 2 × (s 12 +s 22 )]/(m 1 –m 2 ) (46) . Based on this analysis, 52 patients were required for an aripiprazole trial (46) . The random assignment was carried out confidentially by the clinic administration and arranged so that the same number of patients would be treated with the active drug (N=26, 21 women and 5 men) as with a placebo (N=26, 22 women and 4 men).

Between June 2004 and April 2005, the subjects received medication in a blinded manner, which constituted either 15 mg/day of aripiprazole or a matching placebo (47 , 48) . The dosage remained constant. Tablets were supplied in numbered boxes. Both the subjects and the clinicians were blinded regarding the assignment of aripiprazole or placebo. The subjects were tested with the SCL-90-R, the HAM-D, the HAM-A, and the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory every week. During the course of the trial, the intermediate results were not analyzed. After 8 weeks, both groups were tested for the last time and physically examined. Five subjects who missed more than two weekly evaluations dropped out. The questionnaires were filled out by the patients both independently and anonymously.

Data Analysis

We used the statistical program SPSS, Version 11 (SPSS, Chicago). Because the data were not normally distributed, the Mann-Whitney U test was performed for comparison of continuous variables. We employed means, SDs, changes between two groups with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and probability (p) for reporting the treatment results according to the intent-to-treat principle (46) .

Ethical Considerations

The study was planned and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and ethical laws pertaining to the medical profession, and its design was approved by the clinic’s ethics committee. The study was conducted independent of any institutional influence and was not funded.

Results

The patients in the aripiprazole group were a mean age of 22.1 years (SD=3.4) (placebo group: mean=21.2 years, SD=4.6); 11 (42.3%) were in a relationship with a significant other (placebo group: N=9, 34.6%); seven were laborers (26.9%) (placebo group: N=8, 30.8%); 14 were office workers (53.8%) (placebo group: N=15, 57.7%); and five were homemakers (19.2%) (placebo group: N=3, 11.5%).

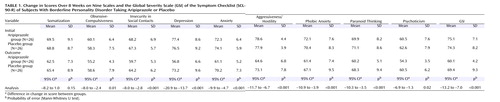

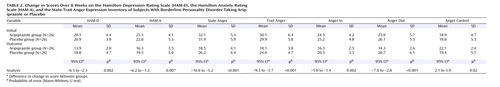

Eighteen had had previous psychotherapy (69.2%) (placebo group: N=19, 73.1%); all had received psychotropic drugs, and 10 had been hospitalized for psychiatric reasons (38.5%) (placebo group: N=11, 42.3%). Their psychiatric comorbidity included depressive disorders (aripiprazole group: N=21, 80.8%; placebo group: N=22, 84.6%), anxiety disorders (aripiprazole group: N=16, 61.5%; placebo group: N=14, 53.8%), obsessive-compulsive disorders (aripiprazole group: N=3, 11.5%; placebo group: N=3, 11.5%), and somatoform disorders (N=18, 69.2%; placebo group: N=19, 73.1%). The patients’ initial measurements with the SCL-90-R ( Table 1 ) and the HAM-D, the HAM-A, and the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory ( Table 2 ) at the time of random assignment revealed no essential differences between the two groups. At the beginning of the study, both groups had distinctly modified SCL-90-R ( Table 1 ), HAM-D, HAM-A, and State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory scores ( Table 2 ), indicating the presence of multiple psychopathological symptoms.

Tables 1 and 2 summarize the rates of change between the aripiprazole and the placebo groups over the course of the entire study. The aripiprazole group experienced a significantly greater rate of change than the placebo group on most of the SCL-90-R scales (with the exception of somatization), as well as on the HAM-D and the HAM-A and all of the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory scales.

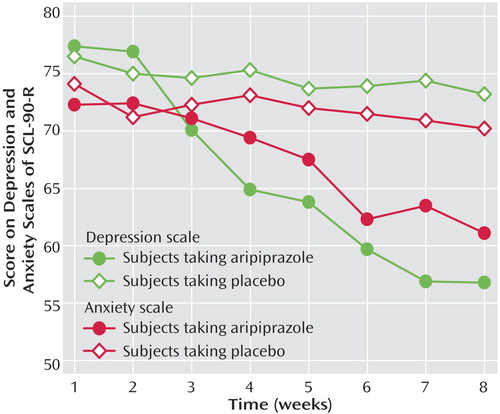

Figure 1 shows the changes over time on the depression and anxiety scales of the SCL-90-R for both groups. On the anxiety scale, aripiprazole was initially associated with a gradual change but on the depression scale, with a rapid change. Self-injury was observed in both groups (8 weeks before therapy—aripiprazole group: seven of 26, placebo group: five of 26; over the 8 weeks of therapy—aripiprazole group: two of 26, placebo group: seven of 26). Neither serious side effects nor suicidal acts were observed during the study. No significant weight changes were observed.

Discussion

Both groups were comparable in light of their sociodemographic and medical data, comorbidity (29 , 49) , and initial measurements with the SCL-90-R, the HAM-D, the HAM-A, and the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory.

Aripiprazole treatment resulted in a significantly greater rate of improvement than did placebo on all of the SCL-90-R scales, especially the obsessive-compulsive, insecurity in social contacts, depression, anxiety (49 , 50) , aggressiveness/hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid thinking, and psychoticism scales (42) . These findings conform to previous reports (3 – 6 , 8 , 12 , 13 , 16) but clearly broaden the range of possible psychological symptoms that can be positively influenced through aripiprazole. In all, aripiprazole resulted in a significant reduction of global psychological stress (as measured by the GSI [ Table 1 ]).

On the HAM-D and the HAM-A scales, the aripiprazole group experienced greater change than the placebo group. The difference in change between both groups was significant, which supports previous findings of antidepressant and anxiolytic effects from aripiprazole (8) .

Aripiprazole treatment resulted in a significantly greater rate of change than did placebo on four State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory scales. Thus, aripiprazole was more effective in treating the aggression component of borderline psychopathology. Among our patients, aripiprazole appeared to influence the intensity of the subjective state of anger (state anger) as well as their readiness to react with anger (trait anger). Furthermore, the tendency to direct anger outward (anger out) and inward (anger in) decreased significantly. This is important because the socially desirable tendency to control anger was strengthened (anger control).

The most common side effects of aripiprazole are headache, insomnia, nausea, numbness, constipation, and anxiety (1 , 2 , 13) . No significant weight change was observed (1 , 2) . This supported findings from Keck et al. (13) that aripiprazole is a safe and well-tolerated agent.

Aripiprazole appears to be a safe and effective agent for improving not only the symptoms of borderline personality disorder but also the associated health-related quality of life and interpersonal problems.

Limitations and Directions for Further Research

Despite a valid power analysis, the group was small. The length of this trial was only 8 weeks, which possibly reduced the failure rate. The study focused on only three dimensions of borderline personality disorder, namely, affective dysregulation, aggressive impulsivity, and cognitive perceptual impairment. The effects of aripiprazole on the fourth dimension—disturbed relationships—were not evaluated. Finally, the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (50) , a new clinician-rated outcome measure specifically designed for borderline personality disorder, was not available in the German language when we began the study. Additional research is needed to see if these results can be replicated and how long-lasting the benefits are.

1. Kasper S, Lerman MN, McQuade RD, Saha A, Carson WH, Ali M, Archibald D, Ingenito G, Marcus R, Pigott T: Efficacy and safety of aripiprazole vs haloperidol for long-term maintenance treatment following acute relapse of schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2003; 6:325–337Google Scholar

2. Potkin SG, Saha AR, Kujawa MJ, Carson WH, Ali M, Stock E, Stringfellow J, Ingenito G, Marder SR: Aripiprazole, an antipsychotic with a novel mechanism of action, and risperidone vs placebo in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:681–690Google Scholar

3. Nasrallah HA, Newcomer JW: Atypical antipsychotics and metabolic dysregulation: evaluating the risk/benefit equation and improving the standard of care. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2004; 24(suppl 1):7–14Google Scholar

4. Hirose T, Uwahodo Y, Yamada S, Miwa T, Kikuchi T, Kitagawa H, Burris KD, Altar CA, Nabeshima T: Mechanism of action of aripiprazole predicts clinical efficacy and a favourable side-effect profile. J Psychopharmacol 2004; 18:375–383Google Scholar

5. Anghelescu I, Wolf J: Successful switch to aripiprazole after induction of hyperprolactinemia by ziprasidone: a case report. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65:1286–1287Google Scholar

6. Marona-Lewicka D, Nichols DE: Aripiprazole (OPC-14597) fully substitutes for the 5-HT1A receptor agonist LY293284 in the drug discrimination assay in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004; 172:415–421Google Scholar

7. Aihara K, Shimada J, Miwa T, Tottori K, Burris KD, Yocca FD, Horie M, Kikuchi T: The novel antipsychotic aripiprazole is a partial agonist at short and long isoforms of D2 receptors linked to the regulation of adenylyl cyclase activity and prolactin release. Brain Res 2004; 1003:9–17Google Scholar

8. Briley M, Moret C: Neurobiological mechanisms involved in antidepressant therapies. Clin Neuropharmacol 1993; 16:387–400Google Scholar

9. DeLeon A, Patel NC, Crismon ML: Aripiprazole: a comprehensive review of its pharmacology, clinical efficacy, and tolerability. Clin Ther 2004; 26:649–666Google Scholar

10. Reeves RR, Mack JE: Worsening schizoaffective disorder with aripiprazole (letter). Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:1308Google Scholar

11. Duggal HS, Kithas J: Possible neuroleptic malignant syndrome with aripiprazole and fluoxetine (letter). Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:397–398Google Scholar

12. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P: Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2004; 7:219–238Google Scholar

13. Keck PE Jr, Marcus R, Tourkodimitris S, Ali M, Liebeskind A, Saha A, Ingenito G, Aripiprazole Study Group: A placebo-controlled, double-blind study of the efficacy and safety of aripiprazole in patients with acute bipolar mania. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:1651–1658Google Scholar

14. Kastrup A, Schlotter W, Plewina C, Bartels M: Treatment of tics in Tourette syndrome with aripiprazole. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2005; 25:94–96Google Scholar

15. Connor KM, Payne VM, Gadde KM, Zhang W, Davidson JR: The use of aripiprazole in obsessive-compulsive disorder: preliminary observations in 8 patients. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66:49–51Google Scholar

16. Jagadheesan K, Muirhead D: Aripiprazole for acute bipolar mania (letter). Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:1926–1927Google Scholar

17. Rinne T, de Kloet ER, Wouters L, Goekoop JG, de Rijk RH, van den Brink W: Fluvoxamine reduces responsiveness of HPA axis in adult female BPD patients with a history of sustained childhood abuse. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003; 28:126–132Google Scholar

18. Flewett T, Bradley P, Redvers A: Management of borderline personality disorder. Br J Psychiatry 2003; 183:78–79Google Scholar

19. Verheul R, Van Den Bosch LM, Koeter MW, De Ridder MA, Stijnen T, Van Den Brink W: Dialectical behaviour therapy for women with borderline personality disorder: 12-month, randomized clinical trial in the Netherlands. Br J Psychiatry 2003; 182:135–140Google Scholar

20. Nickel M, Nickel C, Leiberich P, Mitterlehner F, Tritt K, Forthuber P, Rother W, Loew T: Psychosocial characteristics in people who often change their psychotherapists. Wien Med Wochenschr 2004; 154:163–169Google Scholar

21. Nickel M, Nickel C, Mitterlehner F, Tritt K, Lahmann C, Leiberich P, Rother W, Loew T: Topiramate treatment of aggression in female borderline personality disorder patients: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65:1515–1519Google Scholar

22. Nickel M, Nickel C, Kaplan P, Lahmann C, Mühlbacher M, Tritt K, Krawczyk J, Leiberich PK, Rother W, Loew T: Treatment of aggression with topiramate in male borderline patients: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Biol Psychiatry 2005; 57:495–499Google Scholar

23. MacKinnon DF, Zandi PP, Gershon E, Nurnberger JI, Reich T, De Paulo JR: Rapid switching of mood in families with multiple cases of bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:921–928Google Scholar

24. Crandell LE, Patrick MP, Hobson RP: “Still-face” interactions between mothers with borderline personality disorder and their 2-month-old infants. Br J Psychiatry 2003; 183:239–247Google Scholar

25. Lieb K, Zanarini MC, Schmahl C, Linehan MM, Bohus M: Borderline personality disorder. Lancet 2004; 364:453–461Google Scholar

26. Frankenburg FR, Zanarini MC: The association between borderline personality disorder and chronic medical illnesses, poor health-related lifestyle choices, and costly forms of health care utilization. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65:1660–1665Google Scholar

27. Sher L, Oquendo MA, Li S, Huang YY, Grunebaum MF, Burke AK, Malone KM, Mann JJ: Lower CSF homovanillic acid levels in depressed patients with a history of alcoholism. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003; 28:1712–1719Google Scholar

28. Yen S, Shea MT, Sanislow CA, Grilo CM, Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, McGlashan TH, Zanarini MC, Morey LC: Borderline personality disorder criteria associated with prospectively observed suicidal behavior. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:1296–1298Google Scholar

29. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Silk KR: The longitudinal course of borderline psychopathology: 6-year prospective follow-up of the phenomenology of borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:274–283Google Scholar

30. Friedel RO: Dopamine dysfunction in borderline personality disorder: a hypothesis. Neuropsychopharmacology 2004; 29:1029–1039Google Scholar

31. Hansenne M, Pitchot W, Pinto E, Reggers J, Scantamburlo G, Fuchs S, Pirard S, Ansseau M: 5-HT1A dysfunction in borderline personality disorder. Psychol Med 2002; 32:935–941Google Scholar

32. Oquendo MA, Mann JJ: The biology of impulsivity and suicidality. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2000; 23:11–25Google Scholar

33. Nickel M, Leiberich P, Mitterlehner F: Atypical neuroleptics in personality disorders. Psychodynamic Psychotherapy 2003; 2:25–32Google Scholar

34. Soloff PH, George A, Nathan S, Schulz PM, Cornelius JR, Herring J, Perel JM: Amitriptyline versus haloperidol in borderlines: final outcomes and predictors of response. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1989; 9:238–246Google Scholar

35. Leucht S, Wahlbeck K, Hamann J, Kissling W: New-generation antipsychotics versus low-potency conventional antipsychotics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2003; 361:1581–1589Google Scholar

36. Pascual JC, Oller S, Soler J, Barrachina J, Alvarez E, Perez V: Ziprasidone in the acute treatment of borderline personality disorder in psychiatric emergency services. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65:1281–1282Google Scholar

37. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Panachini EA: A preliminary, randomized trial of fluoxetine, olanzapine, and the olanzapine-fluoxetine combination in women with borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65:903–907Google Scholar

38. Ferrerri MM, Loze JY, Rouillon F, Limosin F: Clozapine treatment of a borderline personality disorder with severe self-mutilating behaviours. Eur Psychiatry 2004; 19:177–178Google Scholar

39. Bogenschutz MP, George NH: Olanzapine versus placebo in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65:104–109Google Scholar

40. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR: Olanzapine treatment of female borderline personality disorder patients: a double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62:849–854Google Scholar

41. Zanarini MC: Update on pharmacotherapy of borderline personality disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2004; 6:66–70Google Scholar

42. Franke GH: SCL-90-R: Symptom-Checkliste von LR Derogatis. Goettingen, Germany, Beltz, 2002Google Scholar

43. Hamilton M: Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1976; 6:278–296Google Scholar

44. Hamilton M: The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol 1959; 32:50–55Google Scholar

45. Schwenkmezger P, Hodapp V, Spielberger CD: The State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory. Goettingen, Germany, Huber, 1992Google Scholar

46. Muellner M: Evidence Based Medicine. Wien, NY, Springer, 2002Google Scholar

47. Davis JM, Chen N: Dose response and dose equivalence of antipsychotics. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2004; 24:192–208Google Scholar

48. Yokoi F, Gruender G, Biziere K, Stephane M, Dogan AS, Dannals RF, Ravert H, Suri A, Bramer S, Wong DF: Dopamine D2 and D3 receptor occupancy in normal humans treated with the antipsychotic drug aripiprazole (OPC 14597): a study using positron emission tomography and [ 11 C]raclopride. Neuropsychopharmacology 2002; 27:248–259 Google Scholar

49. Sasson Y, Chopra M, Harrari E, Amitai K, Zohar J: Bipolar comorbidity: from diagnostic dilemmas to therapeutic challenge. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2003; 6:139–144Google Scholar

50. Zanarini MC, Vujanovic AA, Parachini EA, Boulanger JL, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J: Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD): a continuous measure of DSM-IV borderline psychopathology. J Personal Disord 2003; 17:233–242Google Scholar