Neuropsychological Processing Associated With Recovery From Depression After Stereotactic Subcaudate Tractotomy

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors compared patients who underwent stereotactic subcaudate tractotomy for depression, who were still depressed or recovered from depression, to identify therapeutic mechanisms. METHOD: Ten depressed and eight recovered psychosurgery patients, along with nine never-depressed subjects and nine who had recovered from depression with medication, completed the Iowa Gambling Task, a measure of decision making in the face of feedback. Psychosurgery patients also completed general neuropsychological testing. RESULTS: Recovered psychosurgery patients exhibited insensitivity to negative feedback on the Iowa Gambling Task compared to the other three groups. This difference between the groups remained when general neuropsychological performance was covaried out. CONCLUSIONS: These findings suggest acquired relative insensitivity to negative information as a specific mechanism mediating the antidepressant effect of stereotactic subcaudate tractotomy. Such insensitivity is not secondary to deficits in general neuropsychological functioning and is not a function of recovery from depression per se.

We compared still-depressed and recovered depression patients who had undergone psychosurgery (stereotactic subcaudate tractotomy [1]) in an effort to identify therapeutic mechanisms. We hypothesized that stereotactic subcaudate tractotomy leads to depression recovery by reducing sensitivity to negative information. According to this hypothesis, brain regions involved in negative information processing are less affected by psychosurgery in patients who remain depressed than in patients who recover.

To test this hypothesis, we used the Iowa Gambling Task (2). The Iowa Gambling Task requires participants, on each trial, to choose a card from one of four decks. Every card offers an immediate financial reward. Occasionally, a card also results in a financial penalty. There are two “good” decks in which immediate rewards are modest but occasional penalties are small and two “bad” decks in which although immediate rewards are high, occasional penalties are severe. Consequently, persevering with good decks leads to a net profit and with bad decks to a net loss. The goal is to make a net profit, something healthy participants achieve but patients with ventromedial orbitofrontal cortex damage do not (2). As stereotactic subcaudate tractotomy targets posterior, ventral orbitofrontal cortex white matter (1), these data suggest that Iowa Gambling Task performance is associated with the brain regions compromised by psychosurgery.

On the Iowa Gambling Task, any oversensitivity to negative information (and/or reduced reward-related behavior), as typically shown by depressed patients (3), would render the bad decks aversive and the less punitive good decks appealing. This would lead to unimpaired performance, as is indeed the case in subjects with major depressive disorder (4). In contrast, insensitivity to negative information would reduce the deterrent effect of occasional severe punishments, making the bad decks (with their high immediate rewards) more appealing, resulting in impaired performance on the Iowa Gambling Task.

The present hypothesis therefore predicts that on the Iowa Gambling Task, depression-recovered psychosurgery patients will show greater insensitivity to negative information (in the form of financial punishments) and will be impaired overall, relative to still-depressed psychosurgery patients.

Patients who had stereotactic subcaudate tractotomy completed a neuropsychological test battery to provide a context for interpreting any Iowa Gambling Task differences. None of these tasks involved negative feedback information.

Method

Ten patients who had had stereotactic subcaudate tractotomy for depression and who had remained depressed since their operation (three men; mean age=50.3 years, SD=8.6, range=32–60; major depressive disorder, N=8, and bipolar disorder, N=2, according to the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry [5]) were compared with eight patients who had been largely free of mood episodes since the surgery (two men; mean age=58.0 years, SD=11.3, range=39–75; prior major depressive disorder, N=7; bipolar disorder, N=1). All psychosurgery patients who were still depressed and three who had recovered were medicated. For all patients, postoperative lesions were appropriate as verified by brain scans.

Nine other participants (four men; mean age=39.4 years, SD=7.7, range=24–51; bipolar disorder, N=2; major depressive disorder, N=7) had recovered from depression with medication alone, and nine (two men; mean age=55.7 years, SD=11.1, range=43–76) had no history of depression. After complete description of the study, written informed consent was obtained.

The Iowa Gambling Task was as described. The standard score is the number of choices from good decks minus the number from bad decks. Chance responding yields a score of zero. A positive score represents a net profit and successful performance (2). Insensitivity to negative feedback on the Iowa Gambling Task was the proportion of occasions that participants persevered with one of the bad decks (deck A) immediately following a financial penalty trial on that deck (insensitivity to negative feedback, deck A). There were two reasons for focusing on deck A. First, this computation only makes sense for the bad decks in which insensitivity to negative feedback is disadvantageous in terms of overall task performance. Second, of the two bad decks, it is only in deck A that financial loss (negative feedback) trials are sufficiently frequent (out of 20) to perform valid statistical analyses. Six general neuropsychological tests assessed IQ, memory, language, attention, and executive function.

Results

Psychosurgery groups were comparable on age, IQ, and sex ratio. Depression-recovered psychosurgery patients were postoperative for longer (mean=87.3 months, SD=66.3) than those who were still depressed (mean=28.1 months, SD=23.9) (t=2.4, df=8.5, p<0.05), but this did not relate to any of the variables of interest and so is not discussed further. Never-depressed comparison subjects were comparable on age and IQ with the psychosurgery groups and on Beck Depression Inventory scores with the depression-recovered psychosurgery group. Participants who had recovered from depression with medication were comparable on IQ and Beck Depression Inventory scores with the depression-recovered psychosurgery patients but were younger (t=4.0, df=15, p<0.01).

On the Iowa Gambling Task, both depression-recovered (mean=18.88, SD=37.08) and still-depressed (mean=31.20, SD=29.65) psychosurgery patients selected more cards from good decks than bad, making a net profit. Only the still-depressed psychosurgery patients performed significantly better than chance (t=3.3, df=9, p<0.01) (depression-recovered psychosurgery patients: t=1.4, df=7, p>0.10). However, these groups did not differ significantly from each other. Similar results were obtained by analyzing blocks of 20 trials separately.

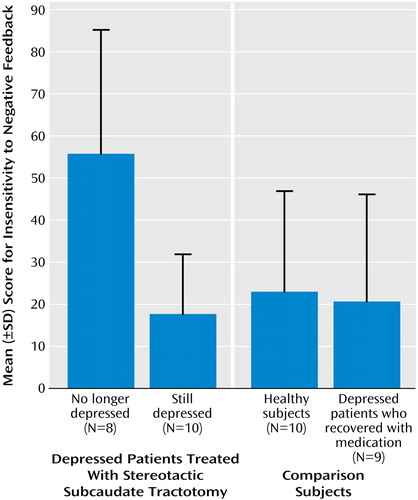

Depression-recovered psychosurgery patients showed greater insensitivity to negative feedback, deck A, than still-depressed psychosurgery patients (Figure 1) (t=3.6, df=16, p<0.002; Cohen’s d=1.65), and there was a negative correlation between insensitivity to negative feedback, deck A, and Beck Depression Inventory scores across all psychosurgery subjects (r=–0.53, p<0.04). These data indicate that on both categorical and continuous measures, greater insensitivity to negative feedback, deck A, was associated with lower depression.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) of insensitivity to negative feedback, deck A scores for recovered and still-depressed psychosurgery patients and healthy comparison subjects revealed a significant difference between groups (F=7.00, df=2, 24, p<0.005) (Figure 1), with depression-recovered psychosurgery patients being more insensitive to negative feedback than healthy comparison subjects (least significant difference test, df=15, p<0.01) and still-depressed psychosurgery patients (least significant difference test, df=16, p<0.005) who did not differ from each other. That is, it was the psychosurgery patients who had recovered from depression who were abnormally insensitive to negative feedback.

It was possible that the insensitivity to negative feedback of depression-recovered psychosurgery patients concerned depression recovery per se and was not specific to stereotactic subcaudate tractotomy. However, ANOVAs comparing depression-recovered psychosurgery patients, patients who recovered from depression with medication, and healthy comparison subjects revealed a significant difference across groups on insensitivity to negative feedback, deck A (F=4.65, df=2, 23, p=0.02) (Figure 1), that was due to the depression-recovered psychosurgery patients being more insensitive than both the subjects who recovered from depression with medication and the never-depressed comparison subjects (least significance difference tests, p values <0.01), who did not differ from each other. This effect remained with age covaried out (F=3.27, df=2, 14, p<0.05).

Finally, the difference in insensitivity to negative feedback, deck A, scores between the two psychosurgery groups remained significant even with the six neuropsychological test scores as covariates (F=8.74, df=1, 9, p<0.02), indicating that it was not secondary to any differences in more general cognitive functions.

Conclusions

Analysis of the Iowa Gambling Task showed that recovery from depression following stereotactic subcaudate tractotomy, on both categorical and continuous measures of depression, was associated with a relative insensitivity to negative information. This insensitivity was not a function of recovery from depression per se because it was not present in patients successfully treated with medication alone. It was also not secondary to general deficits in neuropsychological functioning. The present results therefore suggest that an acquired relative insensitivity to negative information represents a plausible mechanism for the antidepressant effect of stereotactic subcaudate tractotomy.

We should note possible limitations of the findings.

| 1. | We cannot be certain that postoperative differences between psychosurgery groups were not present preoperatively. However, depressed patients generally show increased sensitivity to negative information (3), making it unlikely that the relative insensitivity in depression-recovered psychosurgery patients was present preoperatively when they were experiencing an episode. | ||||

| 2. | Group sizes were relatively small. However, the Iowa Gambling Task was developed for small-group studies, and present group sizes are comparable to those of other studies (2). Nevertheless, there were two areas in which power was a potential problem: the comparison between psychosurgery groups on the Iowa Gambling Task standard score and the comparison of this score against zero (representing chance responding) for the depression-recovered psychosurgery patients. | ||||

| 3. | The still-depressed psychosurgery patients were more medicated than the recovered psychosurgery patients. However, it is not clear how this could account for the key findings of the study, which were a function of abnormal performance in the depression-recovered psychosurgery participants. | ||||

Presented in part at the eighth annual meeting of the Cognitive Neuroscience Society, New York, March 25–27, 2001. Received July 15, 2003; revision received Oct. 29, 2003; accepted Feb. 9, 2004. From the Medical Research Council, Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit, Cambridge; the School of Psychiatry, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia; the Department of Psychiatry, University of Cambridge, Cambridge; and the Department of Psychiatry, Institute of Psychiatry, University of London, London. Address reprint requests to Dr. Dalgleish, MRC CBU, 15 Chaucer Rd., Cambridge CB2 2EF, U.K.; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by the Medical Research Council of the United Kingdom.

Figure 1. Insensitivity to Negative Feedback (% of Trials) on Deck A of the Iowa Gambling Task Measured in Depressed Patients Treated With Stereotactic Subcaudate Tractotomy, Never-Depressed Subjects, and Depressed Subjects Who Recovered With Medication Alone

1. Bridges PK, Bartlett JR, Hale AS, Poynton AM, Malizia AL, Hodgkiss AD: Psychosurgery: stereotactic subcaudate tractotomy: an indispensable treatment. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 165:599–611Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Bechara A, Damasio AR, Damasio H, Anderson SW: Insensitivity to future consequences following damage to human prefrontal cortex. Cognition 1994; 50:7–15Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Beck AT: Depression: Clinical, Experimental, and Theoretical Aspects. New York, Harper & Row, 1967Google Scholar

4. Dunn BD: Exploring the Interaction of Mind and Body in Depression (doctoral thesis). Cambridge, UK, University of Cambridge, School of Biology, 2002Google Scholar

5. Wing JK, Babor T, Brugha T, Burke J, Cooper JE, Giel R, Jablenski A, Regier D, Sartorius N: SCAN: Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:589–593Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar