Anxiety and Depression in Later Life: Co-Occurrence and Communality of Risk Factors

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to examine the comorbidity of and communality of risk factors associated with major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders in later life. METHOD: A random age- and sex-stratified community-based sample (N=3,056) of the elderly (age 55–85 years) in the Netherlands was studied. A two-stage screening design was used, with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale as a screening instrument and the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule as a criterion instrument. Risk factors were measured with well-validated instruments and represented a broad range of vulnerability and stress-related factors associated with anxiety and depression. Multivariate analyses examined risk factors associated with pure major depressive disorder, pure anxiety disorders, and comorbid conditions. RESULTS: Comorbidity was highly prevalent: 47.5% of those with major depressive disorder also met criteria for anxiety disorders, whereas 26.1% of those with anxiety disorders also met criteria for major depressive disorder. While the only variables associated with pure major depressive disorder were younger age and external locus of control, risk factors representing a wide range of both vulnerability and stress were associated with pure anxiety disorders. External locus of control was the only common factor. The group with anxiety disorders plus major depressive disorder had a distinct risk factor profile and may represent those with a more severe disorder. CONCLUSIONS: Although high levels of comorbidity between major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders were found, comparing risk factors associated with pure major depressive disorder and pure anxiety disorders revealed more differences than similarities. Anxiety disorders in later life merit separate study.

Epidemiological studies have shown that depression and anxiety are common throughout the life cycle (1–4). Studies among children, adolescents, and adults, carried out in the community, in primary care, and in treatment settings, have shown that anxiety and depression are closely related (5–9). When self-report rating scales for anxiety and depression are used, typically two or three dimensions of symptoms are found, in which symptoms of depression, or of negative affect, emerge as distinct dimensions. However, in these same studies very high correlations (r=0.50–0.70) between anxiety and depression are found (5–9). When anxiety and depression are assessed at syndrome or diagnostic levels of caseness, high correlations remain. When categorical definitions and strict operational criteria are used, high levels of comorbidity between anxiety disorders and depression are found (10–12). Moreover, studies of adults suggest that both disorders often share common risk factors and that similar interventions may be effective (7, 13–16). These findings have prompted discussion as to the validity of the current classification of mental disorders, with critics suggesting that a dimensional approach may be more appropriate than a categorical classification (7, 13).

Most of the research fuelling the debate about classification has been carried out among younger adults. In late life, dementia and depression have been studied widely (17, 18), while anxiety disorders have received far less attention (19–21). Different patterns of comorbidity may be expected among the elderly than among younger adults because of the fact that the exposure to and the impact of risk factors changes with age. Previous studies suggest that factors indicating longstanding vulnerability, such as family histories and personal histories of affective and anxiety disorders, become less important among the older old; this may be so because the most vulnerable elderly selectively leave the population (3, 4, 22). On the other hand, deteriorating physical health and cognitive decline represent prominent risk factors for the development of anxiety and depression in later life (23, 24). The net effect is that although the pattern of underlying risk factors changes dramatically with age, prevalence rates of anxiety disorders and depression are quite stable (3, 4, 25–27).

The primary aims of the present study were to assess co-occurrence and communality of risk factors associated with anxiety disorders and depression in the elderly. Although high levels of comorbidity were expected, the patterns of risk factors associated with pure anxiety and pure depression were expected to differ.

METHOD

Sampling and Procedure

The Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam is designed as a 10-year study of changes in well-being and autonomy in the older population (28). Sampling procedures and response have been detailed elsewhere (3) but will be briefly described. Random samples of older inhabitants (age 55–85 years) were drawn from population registers in 11 municipalities in three regions of the Netherlands. The sample was stratified for age and sex. To ensure large enough numbers 5 years into the study, the numbers were weighted by using projected survival rates (29), oversampling the older old. For reasons of economy the sample was used in two studies: the Nederlands Stimuleringsprogramma Ouderenonderzoek (NESTOR) leefvormen en sociale netwerken van ouderen (LSN) program and the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. NESTOR-LSN is a study focusing on living arrangements and social networks of older people, funded by the Dutch government (30). Respondents were first interviewed by the NESTOR-LSN team and about 11 months later by one of the interviewers from the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. The response rate for the NESTOR-LSN interview was 62.3%. For the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam, all 3,805 respondents in NESTOR-LSN were approached, of whom 3,107 (81.7%) took part (31). Three hundred ninety-four (10.4%) refused to participate because of lack of interest, 134 (3.5%) were too ill or cognitively impaired to be interviewed, 126 (3.3%) died before being interviewed, and 44 persons (1.2%) could not be contacted. Attrition was related significantly to age but not to sex. As expected, the older old were more often found to be too ill or too cognitively impaired to participate. Because of item nonresponse on the instrument used to screen for depression and anxiety disorders, an additional 51 subjects were lost, leaving a baseline sample of 3,056.

Depressive and anxiety disorders were diagnosed by using a two-stage screening design (32). The second stage of case finding took place in an additional interview, scheduled 2–8 weeks after the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam baseline (average=32.6 days). The response rate was 86.0%. Response was related to age but not to sex (32). When the study was designed, the sensitivity of the screening instrument (the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale [CES-D Scale]) for depression and anxiety disorders was unknown for the elderly in the Netherlands (see description later in this article). Therefore, diagnostic interviews were carried out, not only with subjects who were determined as having depression or anxiety disorders by the CES-D Scale but also with a sizeable, random group of subjects who were determined as not having depression or anxiety disorders by the CES-D Scale. Through the application of sampling probability weights, potential selection bias, caused by the fact that those “missed” by the CES-D Scale may represent a special group of elderly with anxiety disorders or depression, could be prevented. The analyses were carried out on those with complete diagnostic interviews (N=659 subjects; 332 were positive and 327 were negative for depression or anxiety disorders according to the CES-D Scale). All interviews were conducted in the homes of respondents by specially trained and intensively supervised interviewers. Informed consent was obtained before the study, in accordance with legal requirements in the Netherlands. Two sets of interviewers were recruited and trained for the baseline and diagnostic interviews, respectively, ensuring that the same interviewer did not screen for and diagnose depression. All interviews were tape-recorded in order to control the quality of the data. Interviewers worked with laptop computers and were encouraged to record any disturbance in the course of the interview. Interviews were conducted between October 1992 and October 1993.

Measures

Screening.

The CES-D Scale is a 20-item self-report scale that has been widely used in older community samples and has good psychometric properties (33–37) The Dutch translation had similar psychometric properties in three previously studied samples of elderly in the Netherlands (38). The overlap with symptoms of physical illness has been shown to be minimal (39, 40). The CES-D Scale generates a total score that can range from 0 to 60. In order to identify respondents at high risk, we employed the generally used cutoff score of 16 or higher (32–38). To reach this score, subjects had to have had more than five symptoms throughout the past week (32, 33). When the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam was designed, no validated screening tool for late-life anxiety disorders was available (21). A previous study among younger adults suggested that the criterion validity of the CES-D Scale for anxiety disorders was good (34). Therefore, the CES-D Scale was used to screen for both anxiety and depression. In the present sample the sensitivity of the CES-D Scale proved to be excellent for major depression (100%) but less impressive for anxiety disorders (74%) (32). This underscores the importance of conducting diagnostic interviews with both those who were positive and those who were negative for these disorders according to the CES-D Scale.

Diagnosis.

Depressive and anxiety disorders were defined according to DSM-III criteria and were diagnosed by using the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule (41). In the present study 6-month prevalences of major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and phobic disorders, including social phobia and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), were used. In some analyses, the presence of any of the four anxiety disorders was used as a summary variable.

Risk factors.

Risk factors were selected for study by using a vulnerability stress model for anxiety and depression (3, 7). Demographic and socioeconomic variables included age, sex, level of education, urban versus nonurban residence, and marital status. Physical health was measured by self-report and was cross-checked with data supplied by general practitioners (42). Measures included the number of chronic physical illnesses (43) and functional limitations (44). Cognitive impairment was measured through use of the Mini-Mental State (45); a cutoff score of 23–24 indicated cognitive decline (46). Life events included catastrophic events experienced in early childhood (five items regarding parental loss, serious personal illness, neglect, and physical and sexual abuse); extreme experiences during World War II that had had a lasting effect (one item); and interpersonal losses, separations, and conflicts experienced during the past year (seven items). Because of its importance, partner loss was reported on separately. Family histories of affective disorders, anxiety disorders, substance abuse, and conduct disorders were assessed with a questionnaire constructed for the present study. Locus of control is a cognitive psychological, trait-type marker of vulnerability for anxiety and depression. It was defined as the extent to which the individual considered himself or herself to be in control of life, rather than being a victim of fate, and was measured through use of an established questionnaire (47, 48). Measures of the network and social support were constructed from a questionnaire that included detailed questions on both the number and the quality of contacts with members of the social network (10). In this article we report on the size of the contact-network and the reception of both instrumental and emotional support. All scales were previously validated either in comparable samples in the Netherlands or in pilot studies of the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam (28).

Data Analysis

The two-stage screening design implies an overrepresentation of subjects with psychopathology. Because the sensitivity of the CES-D Scale was not perfect and because its sensitivity differed across the disorders under study (higher for major depressive disorder than for anxiety disorders [32]), disregarding the effects of the two-stage screening design may bias the results. Therefore, a weighting procedure was employed, redressing the effect of unequal sampling probabilities. Because the results of analyses with and without sampling probability weights were very similar, all analyses reported are based on unweighted data. In order to control for confounding due to associations among risk factors, multivariate analyses, using logistic regression modeling, were carried out. Both major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders are etiologically heterogeneous, implying a large number of potential risk factors. Because many risk factors were available, parsimonious modeling was necessary to avoid power dropping below acceptable levels. A back-step procedure was therefore employed; the criterion for statistical significance was set at p<0.10. In the analyses, associations with risk factors were assessed, contrasting elderly with anxiety disorders or major depressive disorder with comparison subjects. The control group consisted of all elderly subjects determined not to have depression or anxiety disorders by the CES-D Scale and who had none of the disorders under study. In this way, risk factors were assessed relative to the same comparison group, which avoided biasing the results. Because high levels of comorbidity between major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders were expected, risk factors were studied separately for those with and without comorbid disorders.

RESULTS

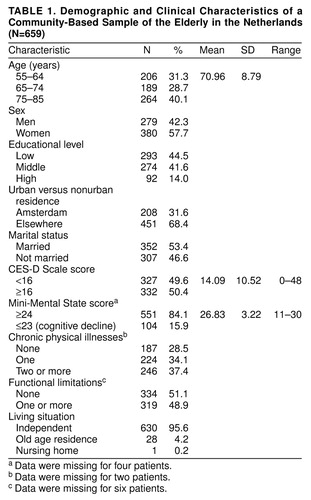

Characteristics of the sample are summarized in table 1. Because of the sampling strategy, the older old, especially the older men, were overrepresented. As intended, half the sample was determined as having depression or anxiety disorders by the CES-D Scale. Important variables, such as cognitive decline (16%), chronic physical illnesses (71%), and functional limitations (49%), were well represented, showing that attrition had not restricted the range of relevant variables.

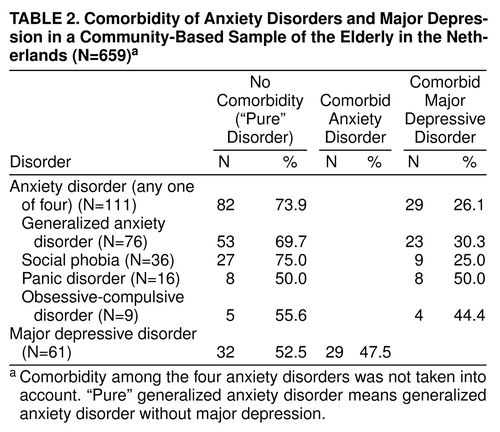

table 2 contains data on the prevalence and comorbidity of major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders. The prevalence in the study sample was artificially raised because of the two-stage screening design. The prevalence in the baseline sample, which was representative of the elderly in the community, has been described elsewhere (major depressive disorder, 2.0%; generalized anxiety disorder, 7.3%; social phobia, 3.1%; panic disorder, 1.0%; OCD, 0.6%; any anxiety disorder, 10.2%) (3, 4). Among those with major depressive disorder, 47.5% had a concurrent anxiety disorder, whereas 26.1% of those with anxiety disorders also met criteria for major depressive disorder. Among the anxiety disorders, concurrent major depressive disorder was most common with panic disorder and OCD, whereas in most cases, generalized anxiety disorder and social phobia were not associated with major depressive disorder. Comorbidity among the anxiety disorders was not very common. Of the 111 elderly with anxiety disorders, 91 had only one anxiety disorder, 14 had two, and six subjects met criteria for three anxiety disorders. This is described in detail elsewhere (49).

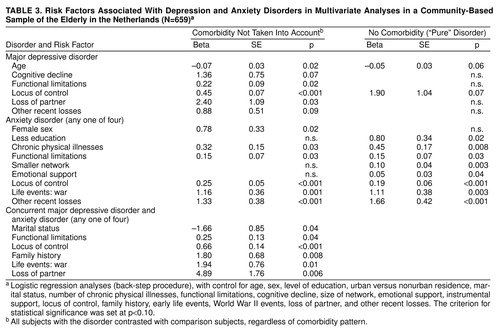

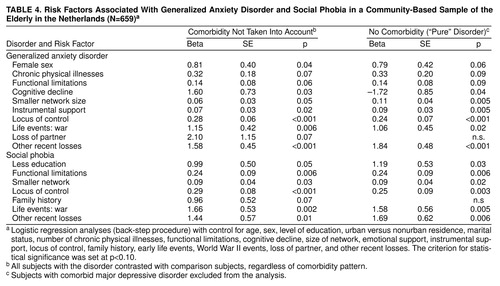

When risk factors associated with pure major depressive disorder and pure anxiety disorders were compared (table 3), the only variables associated with pure major depressive disorder were younger age and external locus of control, whereas a wide range of variables, representing both vulnerability and stress, were associated with pure anxiety disorders. External locus of control was the only, albeit strong, common factor. Family history was associated with only the concurrent anxiety disorders plus major depressive disorder group. Bivariate analyses of risk factors associated with the four specific anxiety disorders have been described elsewhere (4). Because of the low numbers of patients with panic disorder and OCD, examining those with and without major depressive disorder was not fruitful. table 4 shows that comorbidity with major depressive disorder had little effect on the risk factors found for generalized anxiety disorder and social phobia.

DISCUSSION

It has often been suggested that a dichotomous, all-or-nothing type of classification of mental disorders is a rather arbitrary process, which may hinder achieving better understanding of anxiety and depression (7, 13, 14). Examining the risk factors underlying both pure and mixed anxiety and depression is one of the ways to assess the strengths and weaknesses of such classification. Although there are many reasons why both comorbidity patterns and risk factors underlying anxiety and depression may change over the life cycle, systematic studies of comorbidity and communality of risk factors extending into later life have not been carried out.

As was found in previous studies of children, adolescents, and younger adults, high levels of comorbidity were found among major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders (47.5% of those with major depressive disorder had comorbid anxiety disorders; 26.1% of those with anxiety disorders had comorbid major depressive disorder). In a comparison of specific anxiety disorders, comorbid major depressive disorder was more common in panic disorder and OCD (50.0% and 44.4%, respectively) than in generalized anxiety disorder and social phobia (30.3% and 25.0%, respectively). In a comparison of the risk factors associated with pure major depressive disorder, pure anxiety disorders, and concurrent major depressive disorder plus anxiety disorders, more differences than similarities were found. The only factor common to all three was a cognitive, trait-like marker of vulnerability (external locus of control). Pure anxiety disorders were associated with a wide range of vulnerability and stress-related factors, none of which was associated with pure major depressive disorder. Major depressive disorder plus anxiety disorders appears to be more strongly associated with long-term vulnerability factors, such as family history.

Previous studies of late-life depression have not taken into account comorbidity with anxiety disorders. The present data suggest that many of the risk factors often associated with late-life depression may be more appropriately brought in connection with comorbid anxiety. Pure major depressive disorder was associated with very few of the factors studied. It may well be that inclusion of biological or other as yet unknown factors is necessary to achieve better understanding of the etiology of pure major depressive disorder in later life. Locus of control is a cognitive psychological marker of trait vulnerability for both anxiety and depression. The data suggest that anxiety and depression share longstanding personality traits, differing in their relation to environmental risk factors. This is similar to the findings of Kendler et al. (15) that symptoms of anxiety and depression shared genetic factors but had different environmental antecedents .

The present study was carried out among a large, random sample of elderly in the community, thereby avoiding the selection bias inherent in clinical studies. Moreover, anxiety disorders and depression were defined and diagnosed through use of well-established criteria and instruments. However, the study used cross-sectional data; this approach does not permit distinguishing between etiologic and prognostic factors and implies an overrepresentation of chronic “cases.” If the course of anxiety and depressive disorders differs greatly and if their prognosis is determined by different factors, this may explain part of the differences in risk factors found in the present study. In addition, one could interpret the results to imply that the categories of pure anxiety disorders, pure major depressive disorder, and major depressive disorder plus anxiety disorders represent the same disorder but at a different level of severity or at a different stage of development. With respect to severity, it was shown that pure anxiety disorders and pure major depressive disorder were very similar and that major depressive disorder plus anxiety disorders represented a group with more severe symptoms (49). This reflects the stronger association of the group with major depressive disorder plus anxiety disorders with longstanding vulnerability factors. With regard to the previous history, there was no clear pattern, which may explain the present results (49). A final concern is that attrition, which was considerable at all stages of data collection, may have biased the results. Although it is clear that the frailest elderly were at a higher risk of attrition, all relevant variables were well represented in the sample. For studies relying on relative risks, such as the present study, representation of relevant variables is more important than absolute response rates. However, it may be that anxiety and depression exhibit different rates of co-occurrence and risk factors in the very frail. Generalization of results to these elderly is probably limited.

When we take these considerations into account, the findings clearly demonstrate the importance of including data on anxiety disorders when studying late-life depression. Although the comorbidity patterns were very similar to findings in younger age groups, the data on risk factors suggest that in later life, major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, and major depressive disorder plus anxiety disorders represent useful categories, with shared but distinct underpinnings. Further study of their course, severity, and treatment is needed to determine nosological status.

Received Oct. 27, 1998; revision received July 7, 1999; accepted Aug. 5, 1999. From the Department of Psychiatry, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Address reprint requests to Dr. Beekman, Department of Psychiatry, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, PCA Valerius Clinic, Valeriusplein 9, 1075 BG Amsterdam, the Netherlands. The data described were collected in the context of the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam, which is carried out by the Departments of Psychiatry and Sociology and Social Gerontology, Vrije Universiteit, and is funded by the Netherlands Ministry of Welfare, Health and Sports.

|

|

|

|

1. Regier DA, Boyd JH, Burke JD Jr, Rae DS, Myers JK, Kramer M, Robins LN, George LK, Karno M, Locke BZ: One-month prevalence of mental disorders in the United States: based on five Epidemiologic Catchment Area sites. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:977–986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Klerman GL, Lavori PW, Rice J, Reich T, Endicott J, Andreasen NC, Keller MB, Hirschfield RM: Birth-cohort trends in rates of major depressive disorder among relatives of patients with affective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985; 42:689–693Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, van Tilburg T, Smit JH, Hooijer C, van Tilburg W: Major and minor depression in later life: a study of prevalence and risk factors. J Affect Disord 1995; 36:65–75Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Beekman AT, Bremmer MA, Deeg DJ, van Balkom AJ, Smit JH, de Beurs E, van Dyck R, van Tilburg W: Anxiety disorders in later life: a report from the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1998; 13:717–726Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Goldberg DP, Bridges K, Duncan-Jones P, Grayson D: Dimensions of neuroses seen in primary-care settings. Psychol Med 1987; 17:461–470Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Ormel J, Oldehinkel AJ, Goldberg DP, Hodiamont PP, Wilmink FW, Bridges K: The structure of common psychiatric symptoms: how many dimensions of neurosis? Psychol Med 1995; 25:521–530Google Scholar

7. Goldberg D, Huxley PJ: Common Mental Disorders. New York, Routledge, 1992Google Scholar

8. Watson D, Clark LA, Weber K, Assenheimer JS, Strauss ME, McCormick RA: Testing a tripartite model, II: exploring the symptom structure of anxiety and depression in student, adult, and patient samples. J Abnorm Psychol 1995; 104:15–25Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Chorpita BF, Albano AM, Barlow DH: The structure of negative emotions in a clinical sample of children and adolescents. J Abnorm Psychol 1998; 107:74–85Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen HU, Kendler KS: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:8–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Angst J: Comorbidity of mood disorders: a longitudinal perspective study. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1996; 30:31–37Medline, Google Scholar

12. Sartorius N, Ustun TB, Lecrubier Y, Wittchen HU: Depression comorbid with anxiety: results from the WHO study on psychological disorders in primary health care. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1996; 30:38–43Medline, Google Scholar

13. Tyrer P: The Classification of Neurosis. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1989Google Scholar

14. Andrews G, Stewart G, Morris-Yates A, Holt P, Henderson S: Evidence for a general neurotic syndrome. Br J Psychiatry 1990; 157:6–12Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Kendler KS, Heath AC, Martin NG, Eaves LJ: Symptoms of anxiety and symptoms of depression: same genes, different environments? Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:451–457Google Scholar

16. Brown GW, Harris TO, Eales MJ: Social factors and comorbidity of depressive and anxiety disorders. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1996; 30:50–57Medline, Google Scholar

17. Copeland JR, Davidson IA, Dewey ME, Gilmore C, Larkin BA, McWilliam C, Saunders PA, Scott A, Sharma V, Sullivan C: Alzheimer’s disease, other dementias, depression and pseudodementia: prevalence, incidence and three-year outcome in Liverpool. Br J Psychiatry 1992; 161:230–239Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Devanand DP, Sano M, Tang MX, Taylor S, Gurland BJ, Wilder D, Stern Y, Mayeux R: Depressed mood and the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease in the elderly living in the community. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:175–182Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Blazer D, George L, Hughes D: The epidemiology of anxiety disorders: an age comparison, in Anxiety in the Elderly: Treatment and Research. Edited by Salzman C, Lebowitz BD. New York, Springer, 1991, pp 17–30Google Scholar

20. Flint AJ: Epidemiology and comorbidity of anxiety disorders in the elderly. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:640–649Link, Google Scholar

21. Salzman C, Lebowitz BD: Anxiety in the Elderly: Treatment and Research. New York, Springer, 1991Google Scholar

22. van Ojen R, Hooijer C, Jonker C, Lindeboom J, van Tilburg W: Late-life depressive disorder in the community, early onset and the decrease of vulnerability with increasing age. J Affect Disord 1995; 33:159–166Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. van Ojen R, Hooijer C, Bezemer D, Jonker C, Lindeboom J, van Tilburg W: Late-life depressive disorder in the community, II: the relationship between psychiatric history, MMSE and family history. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 166:316–319Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Cervilla JA, Prince MJ: Cognitive impairment and social distress as different pathways to depression in the elderly: a cross-sectional study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1997; 12:995–1000Google Scholar

25. Blazer D: Epidemiology of late life depression, in Diagnosis and Treatment of Late Life Depression: Results of the NIH Consensus Development Conference. Edited by Schneider LS, Reynolds CF III, Lebowitz BD, Friedhoff AJ. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994, pp 9–21Google Scholar

26. Copeland JRM, Beekman ATF, Dewey ME, Hooijer C, Jordan A, Lawlor BA, Lobo A, Magnusson H, Mann AH, Meller I, Prince MJ, Reischies F, Turrina C, deVries MW, Wilson KCM: Depression in Europe: geographical distribution among older people. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 174:312–321Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Beekman ATF, Copeland JRM, Prince MJ: Review of the community prevalence of depression in later life. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 174:307–311Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Deeg DJH, Knipscheer CPM, van Tilburg W: Autonomy and well-being in the aging population: concepts and design of the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam: NIG Trend Studies 7. Bunnik, Netherlands Institute for Gerontology, 1993Google Scholar

29. Statistical Yearbook. Heerlen, Netherlands, Central Bureau of Statistics, 1993Google Scholar

30. van Tilburg T: Losing and gaining in old age: changes in personal network size and social support in a four-year longitudinal study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1998; 53:S313–S323Google Scholar

31. Smits CH, de Vries MZ: Procedures and results of the field work, in Autonomy and Well-Being in the Aging Population: Report From the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam 1992–1993. Amsterdam, Vrije Universiteit Press, 1994Google Scholar

32. Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, Van Limbeek J, Braam AW, De Vries MZ, Van Tilburg W: Criterion validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D): results from a community-based sample of older subjects in The Netherlands. Psychol Med 1997; 27:231–235Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Radloff LS: The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. J Applied Psychol Measurement 1977; 1:385–401Crossref, Google Scholar

34. Breslau N: Depressive symptoms, major depression, and generalized anxiety: a comparison of self-reports on CES-D and results from diagnostic interviews. Psychiatry Res 1985; 15:219–229Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Hertzog C, Van Alstine J, Usala PD, Hultsch DF: Measurement properties of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) in older populations. Psychol Assess 1990; 2:64–72Crossref, Google Scholar

36. Himmelfarb S, Murrell SA: Reliability and validity of five mental health scales in older persons. J Gerontol 1983; 38:333–339Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Radloff LS, Teri L: Use of the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale with older adults. Clinical Gerontologist 1986; 5:119–136Crossref, Google Scholar

38. Beekman AT, van Limbeek J, Deeg DJ, Wouters L, van Tilburg W: [A screening tool for depression in the elderly in the general population: the usefulness of Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)]. Tijdschr Gerontol Geriatr 1994; 25:95–103 (Dutch)Medline, Google Scholar

39. Berkman LF, Berkman CS, Kasl S, Freeman DH Jr, Leo L, Ostfeld AM, Cornoni-Huntley J, Brody JA: Depressive symptoms in relation to physical health and functioning in the elderly. Am J Epidemiol 1986; 124:372–388Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Foelker GA Jr, Shewchuk RM: Somatic complaints and the CES-D. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992; 40:259–262Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Ratcliff KS: National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Its history, characteristics, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 38:381–389Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Kriegsman DM, Penninx BW, van Eijk JT, Boeke AJ, Deeg DJ: Self-reports and general practitioner information on the presence of chronic diseases in community dwelling elderly: a study on the accuracy of patients’ self-reports and on determinants of inaccuracy. J Clin Epidemiol 1996; 49:1407–1417Google Scholar

43. Health Interview Questionnaire. Heerlen, the Netherlands, Central Bureau of Statistics: 1989Google Scholar

44. van Sonsbeek: Methodological and substantial aspects of the OECD indicator of chronic functional limitations. Maandbericht Gezondheid 1988; 88:4–17Google Scholar

45. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Tombaugh TN, McIntyre NJ: The Mini-Mental State Examination: a comprehensive review. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992; 40:922–935Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Pearlin LI, Schooler C: The structure of coping. J Health Soc Behav 1978; 19:2–21Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Smits CH, Deeg DJ, Bosscher RJ: Well-being and control in older persons: the prediction of well-being from control measures. Int J Aging Hum Dev 1995; 40:237–251Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Van Balkom AJLM, Beekman ATF, de Beurs E, Deeg DJH, van Dyck R, van Tilburg W: Comorbidity of anxiety disorders in a community-based elderly population in the Netherlands. Acta Psychiatr Scand (in press)Google Scholar