Differential Effect of Number of Previous Episodes of Affective Disorder on Response to Lithium or Divalproex in Acute Mania

Abstract

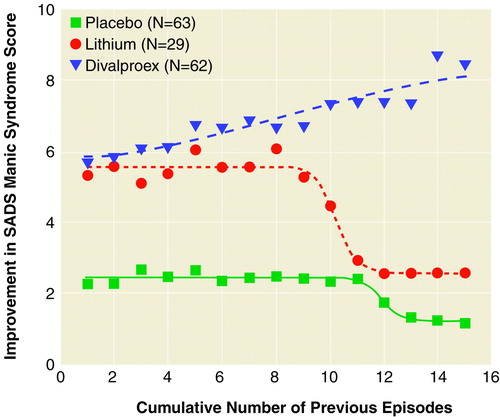

OBJECTIVE: The authors investigated the relationship between number of lifetime episodes of affective disorder and the antimanic response to lithium, divalproex, or placebo. METHOD: The subjects were 154 of the 179 inpatients with acute mania who entered a 3-week parallel group, double-blind study. The primary efficacy measure was the manic syndrome score from the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia. The relationship between improvement and number of previous episodes was investigated by using nonlinear regression analysis. RESULTS: An apparent transition in the relationship between number of previous episodes and response to antimanic medication occurred at about 10 previous episodes. For patients who had experienced more episodes, response to lithium resembled the response to placebo but was worse than response to divalproex. For patients who had experienced fewer episodes, however, the responses to lithium and divalproex did not differ and were better than the response to placebo. This differential response pattern was not related to rapid cycling or mixed states. CONCLUSIONS: A history of many previous episodes was associated with poor response to lithium or placebo but not to divalproex.

Bipolar disorder is a lifelong illness (1). Episode frequency, severity, or sensitivity to stressors may change with time or with repeated episodes (2). Treatment response might also change over time (2, 3), but there is little evidence from controlled studies relating course of illness to response in an acute episode, and there is no information directly comparing effects of illness course on response to different antimanic agents. Therefore, we investigated the effect of the number of previous episodes on response to lithium, divalproex, or placebo in an acute manic episode (4).

METHOD

This multicenter study has been described elsewhere (4), including detailed entrance criteria and descriptions of subjects. It was approved by the institutional review boards of all participating institutions. After complete description of the study to subjects, written informed consent was obtained. Subjects then underwent comprehensive evaluations and were randomly assigned at a 2-1-2 ratio to 3 weeks’ inpatient treatment with divalproex, lithium, or placebo (4). One hundred seventy-nine subjects entered the randomized study; 164 had evaluable treatment outcome data, and 154 had treatment and history data adequate for the analyses in this report. The Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS) (5) and Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) (6) were used to make diagnoses. Subjects were required to meet RDC for an acute primary manic episode. Course of illness was examined in detail by using all available sources of information (4).

We used SAS and Sigma Plot (SPSS, Inc.) for statistical analyses. The dependent variable was change in the SADS manic syndrome score (7). Results of analysis of variance were significant across treatments (F=4.3, df=2, 161, p=0.02). Response to treatment as a function of number of episodes was investigated by using nonlinear fitting to a form of the Hill equation describing a transition between two states (y=yo+axb/[cb+xb]). In this case, y is the SADS mania syndrome score improvement for at least x episodes; yo is the limiting response at a low number of episodes, yo+a is the limiting response at infinite episodes, b is a constant describing the rapidity of the transition, and c is the number of episodes at which the transition is half-maximal. For placebo, R2=0.95; for lithium, R2=0.97; and for divalproex, R2=0.89. Fitted parameters were compared by using a t statistic calculated from the standard error (S) of the parameter P (t=[P1–P2]/√[S12/N1+S22/N2]) (8), with degrees of freedom=N1+N2–4. (N is the number of points in the curve, and 4 is the number of parameters [9], after Bonferroni correction for the nine relevant comparisons [yo, yo+a, and c for the three treatments].)

RESULTS

Figure 1 shows that response to treatment diverged sharply as the number of episodes increased. The values for improvement with a low number of episodes were 5.6 (SD=1.2) for lithium, 5.9 (SD=1.1) for divalproex, and 2.4 (SD=0.7) for placebo. Placebo differed significantly from lithium (t=8.9, df=22, corrected p<0.005) and from divalproex (t=10.4, df=22, corrected p<0.005). The transition between high and low response occurred at 10.2 episodes (SD=0.6) for lithium, 11.9 episodes (SD=0.6) for placebo, and 11.4 episodes (SD=4.6) for divalproex (no differences among treatments). The mean asymptotic response for many episodes was 2.5 (SD=0.6) for lithium, 1.2 (SD=0.4) for placebo, and 9.3 (SD=3.7) for divalproex. The response to divalproex was significantly different from the response to placebo (t=8.4, df=22, corrected p<0.005) and the response to lithium (t=7, df=22, corrected p<0.005).

Patients with many previous episodes may have more mixed states or rapid cycling, which reduce response to lithium. There was no significant relationship, however, between many episodes and mixed states: 38 of 97 subjects with 10 episodes or fewer, versus 27 of 67 with 11 or more, met our previously described criteria for depressive mania (10) (χ2=0.02, df=1, p>0.9). There was a significant increase in current rapid cycling with many episodes (two of 84 subjects with 10 or fewer versus 16 of 56 subjects with 11 or more) (χ2=14.5, df=1, p<0.0005). Only one subject randomly assigned to lithium with more than 10 previous episodes had current rapid cycling. Therefore, the reduced response to lithium occurred among subjects without rapid cycling.

DISCUSSION

A larger number of previous episodes of affective disorder was associated with poor antimanic response to lithium but not to divalproex. This differential treatment response did not result from current rapid cycling or mixed states.

Explanations for reduced response to lithium in subjects with many previous episodes include the following: 1) Lithium resistance may develop with repeated episodes (2). Reduced response to lithium prophylaxis has been reported in patients with many episodes and early onset (3) and in those with more than three previous manic episodes (11). 2) Multiple lithium discontinuations could result in refractoriness to lithium. Most patients, however, have similar responses before and after lithium is discontinued (12, 13). Furthermore, in this study, previous response to lithium predicted current response (4). 3) A group of patients may have frequent episodes that were always lithium resistant, representing an inherently unstable subtype of bipolar disorder. If this proves true, early identification of such patients will be valuable in establishing lifetime treatment strategies.

These results are related only to treatment of acute mania. Further studies are needed to determine whether these relationships extend to maintenance treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Participants in the multicenter trial included A. Brugger, M.D., and D. Morris, Ph.D., Abbott Laboratories; A. Swann, M.D., and S. Dilsaver, M.D., University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston; C. Bowden, M.D., and E. Garza-Trevino, M.D., University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio; F. Petty, M.D., Ph.D., University of Texas Southwestern Medical School at Dallas; J. Calabrese, M.D., Case Western Reserve Medical School; S. Risch, M.D., Medical University of South Carolina; J. Small, M.D., University of Indiana Medical School; P. Goodnick, M.D., University of Miami Medical School; and J. Davis, M.D., and P. Janicak, M.D., Illinois State Psychiatric Institute.

Received Nov. 24, 1997; revisions received Aug. 26 and Nov. 16, 1998, and Jan. 25, 1999; accepted March 4, 1999. From the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and the Harris County Psychiatric Center, University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston. Address correspondence to Dr. Swann, UTMSH Psychiatry, 1300 Moursund St., Rm. 270, Houston TX 77030. Supported in part by Abbott Laboratories and by the Pat R. Rutherford, Jr., Chair in Psychiatry, University of Texas Health Science Center (Dr. Swann). The authors thank their nursing staffs for providing patient care.

FIGURE 1. Relationship Between Previous Episodes of Affective Disorder and Treatment Response in 154 Patients With Acute Maniaa

aThe graph shows improvement in manic syndrome scores for patients randomly assigned to receive lithium, divalproex, or placebo. The lines represent the result of fitting the modified Hill equation using the parameters given in the Results section. The numbers in the legend refer to the total number of patients randomly assigned to the different drug groups for whom comprehensive illness history information was available.

1. Zis AP, Goodwin FK: Major affective disorder as a recurrent illness: a critical review. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1979; 36:835–839Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Post RM, Rubinow DR, Ballenger JC: Conditioning and sensitization in the longitudinal course of affective illness. Br J Psychiatry 1986; 149:191–201Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Maj M: Clinical prediction of response to lithium prophylaxis in bipolar patients: the importance of the previous pattern of course of the illness. Clin Neuropharmacol 1990; 13:S66–S70Google Scholar

4. Bowden CL, Brugger AM, Swann AC, Calabrese JR, Janicak PG, Petty F, Dilsaver SC, Davis JM, Rush AJ, Small JG, Garza-Trevino ES, Risch SC, Goodnick PJ, Morris DD: Efficacy of divalproex vs lithium and placebo in the treatment of mania. JAMA 1994; 271:918–924Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Spitzer RL, Endicott J: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS), 3rd ed. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1978Google Scholar

6. Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E: Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) for a Selected Group of Functional Disorders, 3rd ed. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1978Google Scholar

7. Spitzer RL, Endicott J: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Change Version, 3rd ed. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1978Google Scholar

8. Winer BJ: Statistical Principles in Experimental Design, 2nd ed. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1971, pp 30–31Google Scholar

9. Davidian M, Giltinan DM: Nonlinear Models for Repeated Measurement Data. London, Chapman & Hall, 1995, pp 26–28Google Scholar

10. Swann AC, Bowden CL, Morris D, Calabrese JR, Petty F, Small JG, Dilsaver SC, Davis JM: Depression during mania: treatment response to lithium or divalproex. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:37–42Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Gelenberg AJ, Kane JM, Keller MB: Comparison of standard and low serum levels of lithium for maintenance treatment of bipolar disorders. N Engl J Med 1989; 321:1489–1493Google Scholar

12. Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ, Floris G, Rudas N: Effectiveness of restarting lithium treatment after its discontinuation in bipolar I and bipolar II disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:548–550Link, Google Scholar

13. Coryell W, Solomon D, Leon AC, Akiskal HS, Keller MB, Scheftner WA, Mueller T: Lithium discontinuation and subsequent effectiveness. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:895–898Link, Google Scholar