Brain Development, X

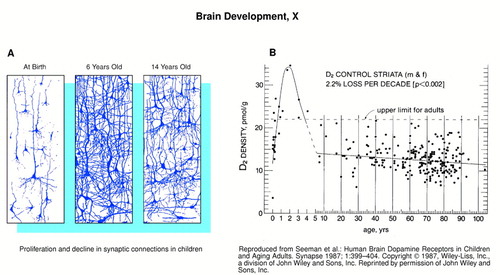

Human brain size changes little over the child and teen years. Nonetheless, considerable cellular and functional change occurs. These maturational changes result in an adult functioning brain and are subject to developmental influence. The images above serve to illustrate this. Figure A shows that at birth, cellular elements are still entering the cortex. By midchildhood, more neurons and more cellular processes are established than in adult years. The developmental task of childhood years from an anatomic point of view is to prune and to select the most useful (perhaps the most used) neurons, synapses, and dendrites to preserve for the adult brain. This process of pruning continues through the early teen years. Presumably, the pruning is accomplished “wisely.” This would mean that synapses that are most important to survival and optimal function flourish whereas useless connections vanish.

One marker of neuronal number is the density of neurotransmitter receptors. In figure B, the density of the dopamine D2 receptor is graphed over a wide age range, beginning immediately after birth and extending to the ninth decade. This graph illustrates the high density of D2 receptors before 5 years of age, a density greater than adult levels, and their regression to adult levels reached during the second decade. Dopamine receptors continue to decrease in adult years, but at a considerably slower rate of 2.2% reduction per decade. This rate is faster in males than in females. But the decrease is slower overall than the tremendous childhood increase in number. In schizophrenia, the rate of D2 receptor loss is faster than in healthy comparison subjects: a 1.9% loss per decade in comparison men and a 6.0% loss per decade in men with schizophrenia.

These data suggest that while certain fixed processes establish the availability of CNS neurons, other influences generated by the organism and the environment serve to determine neuronal survival and connectivity.

Figure A courtesy of Dr. Seeman.

Left Figure

Proliferation and decline in synaptic connections in children

Right Figure

Reproduced from Seeman et al.: Human Brain Dopamine Receptors in Children and Aging Adults. Synapse 1987; 1:399–404. Copyright ” 1987, Wiley-Liss, Inc., a division of John Wiley and Sons, Inc. Reprinted by permission of John Wiley and Sons, Inc.