Superior Temporal Gyrus Volume Abnormalities and Thought Disorder in Left-Handed Schizophrenic Men

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Studies of schizophrenia have not clearly defined handedness as a differentiating variable. Moreover, the relationship between thought disorder and anatomical anomalies has not been studied extensively in left-handed schizophrenic men. The twofold purpose of this study was to investigate gray matter volumes in the superior temporal gyrus of the temporal lobe (left and right hemispheres) in left-handed schizophrenic men and left-handed comparison men, in order to determine whether thought disorder in the left-handed schizophrenic men correlated with tissue volume abnormalities. METHOD: Left-handed male patients (N=8) with DSM-III-R diagnoses of schizophrenia were compared with left-handed comparison men (N=10) matched for age, socioeconomic status, and IQ. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with a 1.5-T magnet was used to obtain scans, which consisted of contiguous 1.5-mm slices of the whole brain. MRI analyses (as previously defined by the authors) included the anterior, posterior, and total superior temporal gyrus in both the left and right hemispheres. RESULTS: There were three significant findings regarding the left-handed schizophrenic men: 1) bilaterally smaller gray matter volumes in the posterior superior temporal gyrus (16% smaller on the right, 15% smaller on the left); 2) a smaller volume on the right side of the total superior temporal gyrus; and 3) a positive correlation between thought disorder and tissue volume in the right anterior superior temporal gyrus. CONCLUSIONS: These results suggest that expression of brain pathology differs between left-handed and right-handed schizophrenic men and that the pathology is related to cognitive disturbance.

Schizophrenia is a chronic, debilitating mental illness that affects approximately 1% of the population and is typically characterized by positive symptoms such as auditory hallucinations and thought disorder. During the past decade, advances in neuroimaging methods to study the brain have resulted in a better understanding of the neuropathological basis of schizophrenia. Yet the relationship between hand dominance and asymmetry of brain pathology in this disorder has attracted little attention. There is, however, a large literature pointing to abnormalities in the temporal lobe, especially left-sided pathology (1–3). Anomalies in the temporal lobe and the superior temporal gyrus have been identified in right-handed schizophrenic men on the basis of evidence from functional (4, 5), structural (6), and histological (7, 8) studies. Moreover, positive symptoms in right-handed schizophrenic men have been linked to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies showing abnormalities in the left anterior (9) and left posterior (10, 11) superior temporal gyrus. With respect to handedness, several investigations have shown that left-handed and right-handed male schizophrenic patients can be dissociated on the basis of anatomical, cognitive, and functional differences. For example, left-handed schizophrenic men have larger lateral ventricles and more cognitive deficits than do right-handed schizophrenic men (12). Electrophysiologically, topographic asymmetries of the P300 peak are right-lateralized in the temporal region in left-handed schizophrenic men, whereas there are left-lateralized P300 asymmetries in right-handed schizophrenic men (5, 13). As a whole, evidence supports left hemisphere pathology in right-handed schizophrenic men. Evidence is emerging, however, that both hemispheres or the right hemisphere are affected in left-handed schizophrenic men.

Given that handedness is related to cerebral organization (14) and that left hemisphere abnormalities have been linked to positive symptoms in right-handed schizophrenic men, findings of altered asymmetry in left-handed schizophrenic men would contribute additional evidence that underlying neuropathology may be linked not only to mechanisms determining cerebral dominance, but also to handedness in schizophrenic men. Because of the limited number of studies in this area and the reported left-sided abnormalities in right-handed schizophrenic men, we were interested in whether left-handed schizophrenic men would show reversed or more symmetric low volumes in the superior temporal gyrus than are present in right-handed schizophrenic men and also whether the anatomical abnormalities would correlate with thought disorder. We hypothesized that left-handed schizophrenic men would have significantly lower volumes in the right and left superior temporal gyrus or in the right superior temporal gyrus and that these volume differences would be correlated with formal thought disorder.

METHOD

Subjects

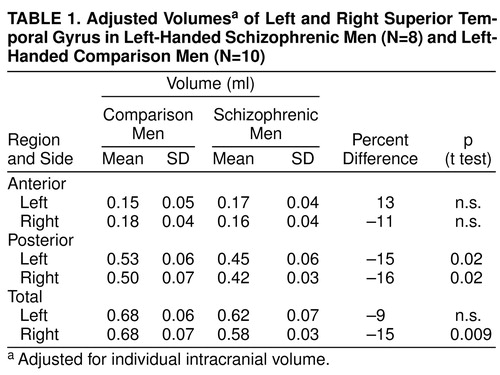

We tested eight left-handed male patients and 10 left-handed male comparison subjects. The patients, who met the DSM-III-R diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia, were recruited from several Boston-area psychiatric hospitals; the comparison subjects were recruited through advertisements. Both groups had not undergone ECT, had no history of neurologic illness, had no alcohol or drug dependence, and had had no significant alcohol or drug abuse in the previous 5 years. The mean ages were 38 years (SD=9) for the patients and 31 years (SD=8) for the comparison subjects. The mean scores on the information subtest of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Revised (WAIS-R) (15) were 10.8 (SD=2) for the patients and 12.7 (SD=2) for the comparison subjects. The comparison subjects had no history of psychiatric illness, nor did their first-degree relatives. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in head circumference, age, socioeconomic status of family of origin, or score on the WAIS-R information subscale. To determine handedness we used the Edinburgh inventory (16), which ranges from –100 to 100, because we were interested in the degree and direction of handedness. The mean handedness quotients were –83.5 (SD=17) for the patients and –55 (SD=10) for the comparison subjects (Figure 1). All of the subjects were fully informed about the study, and all gave written informed consent.

Thought Disorder Assessment

Harrow and Quinlan’s comprehensive assessment of thought disorder (17) was used to evaluate the patients for the presence and severity of thought disorder. This measure has been found to correlate significantly with Johnston and Holzman’s Thought Disorder Index (18). Harrow and Quinlan’s measure evaluates the major phenomena of formal thought disorder, including peculiar speech, confusion, and tangentiality (19), with scores derived from the WAIS-R comprehension subtest (15) and the Gorham Proverbs Test (20). Five categories are used to assess thought disorder: 1) linguistic form and structure, 2) content of the statement, 3) intermixing, 4) relationship between the question and the response, and 5) behavior (19). Scaled scores indicate the level of thought disorder: 1=none, 2=mild, 3=definite, 4=severe, and 5=very severe. The patients’ mean thought disorder score was 3.9 (SD=0.69). To evaluate scoring reliability, two raters independently scored the thought disorder measures. The average intraclass correlation (ri) was 0.92. The comparison subjects were evaluated with the MMPI, and all scored within the normal range (no significant elevations on any clinical scale).

Image Acquisition and Processing

MRI images were obtained on a 1.5-T General Electric SIGNA system (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee), and the scans consisted of contiguous 1.5-mm slices of the whole brain. We used the MRI protocol that we have previously used, which is described in full detail elsewhere (10, 21) Neuroradiological evaluation of the MRI scans showed no gross pathology or clinically defined abnormalities. Image processing was carried out on workstations (Sun Microsystems, Mountain View, Calif.) with multistep algorithms, which included a preprocessing filter to improve the signal-to-noise ratio and segmentation algorithms to assign voxels to specific classes of tissue, e.g., gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid. As in our previous studies, gray matter regions of interest for each spoiled gradient-recalled acquisition image were displayed on a workstation screen and outlined manually by one operator (blind to diagnosis). To evaluate the reliability of the measurements, a second rater (also blind to diagnosis) measured 110 slices from four sets of data (25–30 slices/set) from the left and right total superior temporal gyrus for two randomly selected subjects (one from each group). The average intraclass correlation (ri) was 0.85.

Regions of Interest

To define anterior, posterior, and total superior temporal gyrus (right and left hemispheres), we used the same methods and landmarks that we previously used to outline regions of interest (10, 22). In keeping with our earlier studies, the most anterior boundary of the anterior superior temporal gyrus was identified as the first slice showing the white matter tract (temporal stem) connecting the temporal lobe with the base of the brain. The most posterior boundary of the anterior superior temporal gyrus was identified as the last slice before the appearance of the mammillary bodies. For the posterior superior temporal gyrus, the most anterior boundary was identified as the first slice on which the mammillary bodies appeared. The most posterior boundary of the posterior superior temporal gyrus was defined as the slice where the fibers of the crux of the fornix last appeared. The total superior temporal gyrus region was the sum of the anterior and posterior regions.

RESULTS

The volumetric analyses were corrected for intracranial volume to normalize for differences in head size. Accordingly, relative volumes were obtained by dividing the volume of the intracranial contents and multiplying by 100. All statistical analyses were based on relative volumes. The effects of region and laterality on the volumes of superior temporal gyrus structures were analyzed by using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), which was followed by Scheffe planned comparisons in which the p value was set at ≤0.02. Spearman’s rho (rs) was used to correlate thought disorder scores with left and right anterior, posterior, and total superior temporal gyrus regions. Asymmetry coefficients were computed for each superior temporal gyrus region (right – left) / 0.5 × (right + left) (23). Kendall’s tau-b was used to correlate asymmetry measures with superior temporal gyrus regions because of tie values. All p values are based on two-tailed tests.

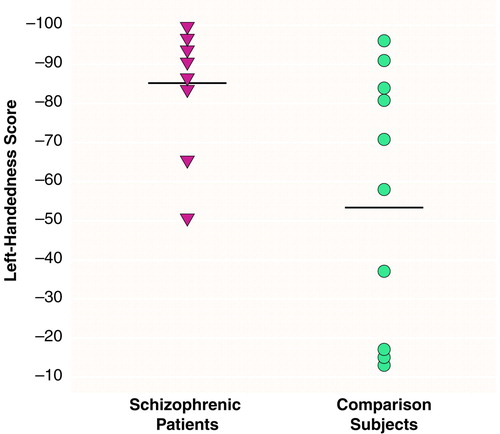

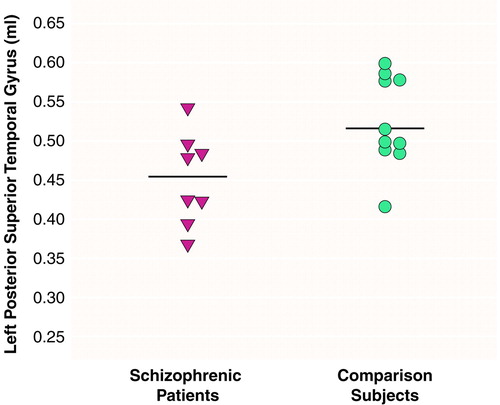

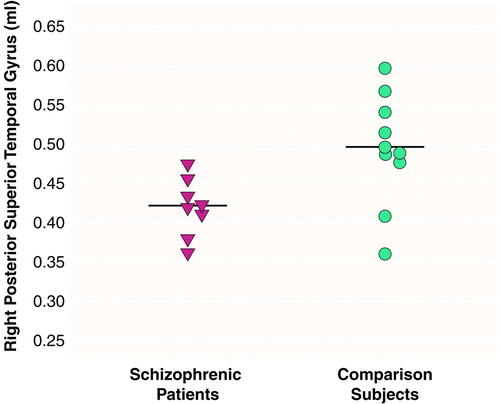

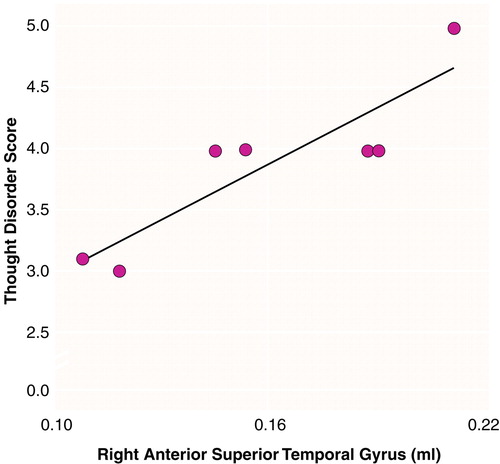

There were significant effects of diagnosis (F=6.83, df=1, 16, p<0.01) and region (F=290.65, df=2, 15, p<0.001) and a significant diagnosis-by-region interaction (F=4.43, df=2, 15, p<0.05), indicating different volume patterns in the patients and comparison subjects. The patients showed significantly smaller volumes bilaterally in the posterior superior temporal gyrus: 15% less volume in the left posterior region (t=2.68, df=16, p<0.02) (table 1 and Figure 2) and 16% less volume in the right posterior region (t=2.69, df=16, p<0.02) (table 1 and Figure 3). The patients also showed significantly lower volume in the right total superior temporal gyrus (t=2.95, df=16, p<0.01) but not in the left total superior temporal gyrus (table 1). Contrary to our expectations, the left-handed patients showed a positive correlation between severity of thought disorder and right anterior superior temporal gyrus volume (rs=0.87, N=7, p=0.005) (Figure 4).

The patients were significantly more left-handed than the comparison men (t=2.17, df=16, p<0.05) (Figure 1). Removing three comparison subjects whose handedness quotients were below –20 resulted in the same general direction of differences, e.g., a significant diagnosis-by-region interaction (F=4.69, df=2, 12, p<0.05), indicating that the handedness difference did not affect the results. The patients also had significantly less intracranial content than the comparison men (t=2.24, df=16, p<0.05). Two of the three comparison subjects who scored less than –20 on the handedness scale also had the highest values for intracranial content. Without their data, there was no significant difference in intracranial content between the groups.

Analyses of asymmetry coefficients (absolute values) yielded three significant correlations. First, the patients showed a significant negative correlation between asymmetry in the anterior superior temporal gyrus and volume of the right anterior region (tau-b=–0.57, N=8, p<0.05), indicating that as asymmetry decreases the right anterior superior temporal gyrus gets larger. Second, the comparison men showed a significant negative correlation between asymmetry in the anterior superior temporal gyrus and volume of the left anterior region (tau-b=–0.50, N=10, p<0.05), demonstrating that the left anterior superior temporal gyrus gets bigger as asymmetry decreases. Third, there was a significant positive correlation for the comparison men between asymmetry in the posterior superior temporal gyrus and the volume of the left posterior region (tau-b=0.51, N=10, p<0.05), showing that the left posterior superior temporal gyrus gets larger as asymmetry increases. There were no other significant correlations for either group.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first MRI study to investigate superior temporal gyrus abnormalities in left-handed schizophrenic men. Our results, which showed bilaterally low volume in the posterior superior temporal gyrus and low right-side volume in the total superior temporal gyrus, differ from the numerous findings of unilaterally low volume in the left superior temporal gyrus of many right-handed schizophrenic men (6, 9–11). Similarly, our finding of a positive correlation between thought disorder and greater volume of the right anterior superior temporal gyrus is opposite to previously reported negative correlations between positive symptoms and low left superior temporal gyrus volume in right-handed schizophrenic men (9–11). These differences may reflect abnormalities in neuropathology that are part of the schizophrenic disorder in men who are left-handed, a relationship that has been hypothesized (24) but heretofore lacking in empirical data.

In normal subjects, 25%–85% of left-handers show nonstandard asymmetry of the superior temporal gyrus, i.e., bilateral symmetry (left same as right) or reversed asymmetry (left less than right) compared to the standard asymmetry (left greater than right) found in many right-handers (25–27). Our left-handed comparison subjects showed nonstandard asymmetry in the total (left same as right) and anterior (right greater than left) superior temporal gyrus. Our findings are consistent with those from other studies of left-handed men (25–27).

MRI studies of the superior temporal gyrus in right-handed schizophrenic patients have shown low volume (9–11, 28–30) and no differences (31, 32). The left-lateralized low volumes in right-handed schizophrenic patients (9–11) may be a neuropathological expression of the standard asymmetry (left greater than right) shown for right-handed normal men in MRI studies (25–27) and postmortem studies (23). Similarly, the bilateral and right-lateralized low volumes in our left-handed schizophrenic patients may be a neuropathological expression of nonstandard superior temporal gyrus asymmetry (bilateral or reversed), consistent with our left-handed comparison subjects and subjects in other studies (25–27). Thus, it may not be that schizophrenia is lateralized left or right but, rather, that its pathology is related to handedness (33), affects cortical volume, and alters degree and direction of asymmetry (34).

The correlation between greater thought disorder and greater volume in the right anterior superior temporal gyrus in the left-handed patients is contrary to our prediction that thought disorder would be associated with lower superior temporal gyrus volume (left or right). A similar finding was reported for right-handed schizophrenic patients but without measures of handedness (32), a factor that may have influenced those results. In our left-handed patients, the positive correlation may be explained by the abnormal asymmetry in the anterior superior temporal gyrus. We suggest that the abnormal asymmetry, driven by the relatively lower volume of the right anterior region and preservation or even greater volume of the left anterior region, may reflect the disturbance of the normal anatomical relationships and consequently may be associated with greater thought disorder. The anterior and posterior portions of the superior temporal gyrus are linked functionally and by anatomical connections. The positive correlation between thought disorder and volume of the right anterior region may, therefore, reflect a flawed reorganization of the right superior temporal gyrus functionality and its anatomical substrate occurring as a result of abnormalities throughout the posterior portion of the superior temporal gyrus, both left and right.

Our findings provide a broader context for the research into left-lateralized superior temporal gyrus abnormalities in right-handed schizophrenic men by demonstrating bilateral and right-lateralized abnormalities in left-handed schizophrenic men. With the caveat that our findings are based on a small number of subjects, these data and those from previous studies (5, 13) support the view that handedness is a strongly differentiating variable in studies of schizophrenia. However, other variables, such as gender, also need to be studied, particularly since left-handedness appears more in males than in females (35) and gender differences have been reported in MRI studies of schizophrenia (36, 37).

In conclusion, our findings show that handedness is a major contributor to differences in the brain pathology of schizophrenia. Taken together with language-related abnormalities in the superior temporal gyrus of right-handed schizophrenic men, our data are consistent with the proposal that the pathology of brain asymmetry is related to cognitive dysfunction and handedness in schizophrenic men. These findings are important because they afford a possible clue to underlying mechanisms of schizophrenia, namely that this disorder may be linked to neurodevelopmental factors influencing language, cerebral asymmetry, and handedness.

Received Feb. 6, 1998; revision received March 19, 1999; accepted March 26, 1999. From the Departments of Psychiatry, Neurology, and Radiology, Harvard Medical School, Boston; the Departments of Psychiatry and Neurology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center; the Clinical Neuroscience Division, Laboratory of Neuroscience, Department of Psychiatry, Brockton/West Roxbury VA Medical Center, Brockton, Mass.; and the Department of Radiology, MRI Division, Surgical Planning Laboratory, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. Address reprint requests to Dr. Holinger, Departments of Psychiatry and Neurology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, 330 Brookline Ave., Boston, MA 02215; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grant MH-55719 and a grant from the EJLB Foundation to Dr. Holinger; by NIMH grants MH-50740 and MH-01110 to Dr. Shenton; by grant CA-67165 from the National Cancer Institute, grant AG-04953 from the National Institute on Aging, and grant NSF-9631710 from the National Science Foundation to Dr. Kikinis; by grant CA-45743 from the National Cancer Institute to Dr. Jolesz; and by NIMH grant MH-40799 and a Department of Veterans Affairs Schizophrenia Center and MERIT award to Dr. McCarley. The authors thank Drs. Steven F. Faux and Gordon F. Sherman for comments on the manuscript, Ms. Marianna Jakab for technical assistance, and Ms. Gauri R. Pandit and Ms. Maria A. Manganiello for administrative assistance.

|

FIGURE 1. Handedness Quotients for Left-Handed Schizophrenic Men (N=8) and Left-Handed Comparison Men (N=10) a

aDetermined with the Edinburgh Inventory (16). The score was based on the formula (R+L)/(R–L)×100. A more negative score indicates greater left-handedness.

FIGURE 2. Individual Adjusted Volumesa of the Left Posterior Superior Temporal Gyrus in Left-Handed Schizophrenic Men (N=8) and Left-Handed Comparison Men (N=10) b

aAdjusted for individual intracranial volume.

bMeans for each group are indicated by horizontal lines.

FIGURE 3. Individual Adjusted Volumesa of the Right Posterior Superior Temporal Gyrus in Left-Handed Schizophrenic Men (N=8) and Left-Handed Comparison Men (N=10) b

Adjusted for individual intracranial volume.

aMeans for each group are indicated by horizontal lines.

FIGURE 4. Relation of Thought Disorder to Individual Adjusted Volumesa of the Right Anterior Superior Temporal Gyrus for Left-Handed Schizophrenic Men (N=7) b

aAdjusted for individual intracranial volume.

bThought disorder was assessed with Harrow and Quinlan’s comprehensive assessment of thought disorder (17). A thought disorder score was not obtained for one of the eight left-handed patients.

1. Crow TJ: Temporal lobe asymmetries as the key to the etiology of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1990; 16:433–443Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Waddington JL: Neurodynamics of abnormalities in cerebral metabolism and structure in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1993; 19:55–69Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Petty RG, Barta PE, Pearlson GD, McGilchrist IK, Lewis RW, Tien AY, Pulver A, Vaughn DD, Casanova MF, Powers RE: Reversal of asymmetry of the planum temporale in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:715–721Link, Google Scholar

4. Faux SF, Shenton ME, McCarley RW, Nestor PG, Marcy B, Ludwig A: Preservation of P300 event-related potential topographic asymmetries in schizophrenia with use of either linked-ear or nose reference sites. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1990; 75:378–391Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Holinger DP, Faux SF, McCarley RW, Shenton ME, Sokol NS, Seidman LJ, Green AI: Reversed temporal region asymmetries of P300 topography in left- and right-handed schizophrenic subjects. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1992; 84:532–537Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Shenton ME, Wible CG, McCarley RW: A review of magnetic resonance imaging studies of brain abnormalities in schizophrenia, in Brain Imaging in Clinical Psychiatry. Edited by Krishnan KRR, Doraiswamy PM. New York, Marcel Dekker, 1997, pp 297–380Google Scholar

7. Falkai P, Bogerts B, Schneider T, Greve B, Pfeiffer U, Pilz K, Gonsiorzcyk C, Majtenyi C, Ovary I: Disturbed planum temporale asymmetry in schizophrenia: a quantitative post-mortem study. Schizophr Res 1995; 14:161–176Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Holinger DP, Rosen GD, Galaburda AM: Decreased neuronal density in supragranular layers of area Tpt of the superior temporal gyrus of schizophrenics. Abstracts of the Society for Neuroscience 1995; 21:238Google Scholar

9. Barta PE, Pearlson GD, Powers RE, Richards SS, Tune LE: Auditory hallucinations and smaller superior temporal gyrus volume in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:1457–1462Google Scholar

10. Shenton ME, Kikinis R, Jolesz FA, Pollack SD, Lemay M, Wible CG, Hokama H, Martin J, Metcalf D, Coleman M, McCarley RW: Left-lateralized temporal lobe abnormalities in schizophrenia and their relationship to thought disorder: a computerized, quantitative MRI study. N Engl J Med 1992; 327:604–612Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Menon RR, Barta PE, Aylward EH, Richards SS, Tien AY, Harris GJ, Pearlson GD: Posterior superior temporal gyrus in schizophrenia: gray matter changes and clinical correlates. Schizophr Res 1995; 16:127–135Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Katsanis J, Iacano WG: Association of left-handedness with ventricle size and neuropsychological performance in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146:1056–1058Google Scholar

13. Holinger DP, DuRand CJ, O’Donnell BF, McCarley RW: Lateralized P300 voltage asymmetries in left-handed and right-handed schizophrenics: an update, in 1994 Annual Meeting New Research Program and Abstracts. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994, p 38Google Scholar

14. Geschwind N, Galaburda AM: Cerebral Lateralization: Biological Mechanisms, Associations, and Pathology. Cambridge, Mass, MIT Press, 1987Google Scholar

15. Wechsler D: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Revised. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich), 1981Google Scholar

16. Oldfield RC: The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 1971; 9:97–113Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Harrow M, Quinlan DM: Disordered Thinking and Schizophrenic Psychopathology. New York, Gardner Press, 1985Google Scholar

18. Marengo JT, Harrow M, Lanin-Kettering L, Wilson A: Evaluating bizarre-idiosyncratic thinking: a comprehensive index of positive thought disorder. Schizophr Bull 1986; 12:497–511Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Marengo JT, Harrow M: Schizophrenic thought disorder at follow-up: its persistence and prognostic significance. Schizophr Bull 1986; 12:373–393Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Gorham DR: Proverbs Test for Clinical and Experimental Use. Psychol Rep Monogr 1956; 1Google Scholar

21. Shenton ME, Kikinis R, McCarley RW, Metcalf D, Tieman J, Jolesz FA: Application of automated MRI volumetric measurement techniques to the ventricular system in schizophrenics and normal controls. Schizophr Res 1991; 5:103–113Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. McCarley RW, Shenton ME, O’Donnell BF, Faux SS, Kikinis R, Jolesz FA: Auditory P300 abnormalities and left posterior superior temporal gyrus volume reduction in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:190–197Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Galaburda AM, Corisglia J, Rosen GD, Sherman GF: Planum temporale asymmetry, reappraisal since Geschwind and Levitsky. Neuropsychologia 1987; 25:853–868Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Crow TJ: Left brain, retrotransposons, and schizophrenia. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986; 293:3–4Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Steinmetz H, Volkmann J, Jäncke L, Freund H-J: Anatomical left-right asymmetry of language-related temporal cortex is different in left- and right-handers. Ann Neurol 1991; 29:315–319Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Habib M, Touze F, Galaburda AM: Intrauterine factors in sinistrality: a review, in Left-Handedness: Behavioral Implications and Anomalies. Edited by Coren S. New York, Elsevier Science, 1990, pp 99–128Google Scholar

27. Foundas AL, Leonard CM, Heilman KM: The pars triangularis and the planum temporale. Arch Neurol 1995; 52:501–508Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Flaum M, Swayze VW II, O’Leary DS, Yuh WTC, Ehrhardt JC, Arndt SV, Andreasen NC: Effects of diagnosis, laterality, and gender on brain morphology in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:704–714Link, Google Scholar

29. Schlaepfer TE, Harris GJ, Tien AY, Peng LW, Lee S, Federman EB, Chase GA, Barta PE, Pearlson GD: Decreased regional cortical gray matter volume in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:842–848Link, Google Scholar

30. Zipursky RB, Marsh L, Lim KO, DeMent S, Shear PK, Sullivan EV, Murphy GM, Csernansky JG, Pfefferbaum A: Volumetric MRI assessment of temporal lobe structures in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 1994; 35:501–506Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Kulynych JJ, Vladar K, Jones DW, Weinberger DR: Superior temporal gyrus volume in schizophrenia: a study using MRI morphometry assisted by surface rendering. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:50–56Link, Google Scholar

32. Vita A, Dieci M, Giobbio GM, Caputo A, Ghiringhelli L, Comazzi M, Garbarini M, Mendini AP, Morganti C, Tenconi F, Cesana B, Invernizzi G: Language and thought disorder in schizophrenia: brain morphological correlates. Schizophr Res 1995; 15:243–251Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Saugstad LF: Cerebral lateralization and rate of maturation. Int J Psychophysiol 1998; 28:37–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Holinger DP, Galaburda AM, Harrison PJ: Cerebral asymmetry and schizophrenia, in The Neuropathology of Schizophrenia. Edited by Roberts GW, Harrison PJ. Oxford, England, Oxford University Press (in press)Google Scholar

35. Porac C, Coren S: Lateral Preferences and Human Behavior. New York, Springer-Verlag, 1981Google Scholar

36. DeLisi LD, Hoff HL, Neale C, Kushner M: Asymmetries in the superior temporal lobe in male and female first-episode schizophrenic patients: measures of the planum temporale and superior temporal gyrus by MRI. Schizophr Res 1994; 12:19–28Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Cowell PE, Kostianovsky DJ, Gur RC, Turetsky BI, Gur RE: Sex differences in neuroanatomical and clinical correlations in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:799–805Link, Google Scholar