Efficacy of Psychoeducational Group Therapy in Reducing Symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Among Multiply Traumatized Women

Abstract

Objective: The role of group therapy in treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has been traditionally restricted to issues of self-esteem and interpersonal relationships, rather than primary symptoms of the disorder. In this study, the authors examined the effectiveness of a 16-week trauma-focused, cognitive-behavioral group therapy, named Interactive Psychoeducational Group Therapy, in reducing primary symptoms of PTSD in five groups (N=29) of multiply traumatized women diagnosed with chronic PTSD. Method: The authors made assessments at baseline, at 1-month intervals during treatment, at termination, and at 6-month follow-up by using self-report and structured interview measures of PTSD and psychiatric symptoms. The absence of a control group limits the conclusions drawn from the study.Results: At termination, subjects showed significant reductions in all three clusters of PTSD symptoms (i.e., reexperiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal) and in depressive symptoms; they showed near-significant reductions in general psychiatric and dissociative symptoms, at termination. These improvements were sustained at 6-month follow-up.Conclusions: The role of group therapy in PTSD treatment should not be prematurely restricted to addressing self-esteem and interpersonal dimensions only. The use of structured, cognitive-behavioral elements within the group format may allow for more targeted treatment of core symptoms of the disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155: 1172-1177

Increasing attention to the impact of childhood sexual abuse and adult sexual assault on the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other psychiatric syndromes has led to a concomitant effort to design and evaluate effective treatment strategies. In this study, we attempted to evaluate the efficacy of a psychoeducational group therapy format for multiply traumatized, chronically ill women.

Only within the past two decades has the magnitude of problems resulting from sexual abuse and violence against women come to be appreciated (1-3). Approximately 20%–25% of all women report a history of sexual abuse during childhood (4). Russell (4) found that 38% of a community cohort of women reported having had childhood sexual contact with an adult and 41% reported at least one experience that met the legal definition of rape. In their survey of criminal victimization in four community cohorts of adult women, Kilpatrick and Resnick (5) found a substantial history of sexual assault (39%), completed rape (18%), and physical assault (11%).

Childhood sexual abuse has been associated with long-term psychiatric problems in adult life including dissociative and posttraumatic stress disorders, depression, anxiety, phobia, substance abuse, eating disorders, suicidality, self-destructive behaviors, problems in interpersonal and intimate relationships, impaired self-esteem, and impaired identity formation (6-9). While there has been no definitive study to show a causal link between character pathology and childhood experience of sexual abuse, there appears to be a close association (10-13). For example, Herman et al. (10) found that 81% of patients diagnosed with borderline personality disorder reported histories of childhood trauma; of those, 68% reported a history of sexual abuse.

The combined effects of childhood and adulthood traumas that are hypothesized to cause psychiatric symptoms, behavior disturbances, and distortions in personality have been termed complex posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or disorders of extreme stress, although the degree to which this condition can be differentiated from PTSD is the subject of significant debate (14, 15). This condition is characterized by alterations in regulation of affect, attention, self-perception, interpersonal relations, systems of meaning, and somatization (15). Patients with such disorders have been found to be difficult to treat, because of both the complexity of their symptom picture and the fact that treatment is usually initiated many years after the traumatic events (10, 16). These patients, therefore, have the potential to absorb a greater percentage of health care costs in terms of support services, disability payments, and hospital costs. Thus, because of both the high prevalence and difficult treatment challenge, efforts to find effective treatments are of significance.

Group therapy has been widely used in the treatment of women with a history of childhood abuse, sexual assault, and other types of traumas (17-21). Group treatment has been proposed as effective in enhancing self-esteem and hopefulness, reducing mistrust, improving interpersonal skills, and reducing social isolation (16, 19, 20). However, reduction of PTSD symptoms has more often been the aim of individual treatment (22, 23), leading many clinicians to recommend group therapy after an initial course of individual therapy (16, 24, 25).

Empirical inquiry into treatment outcome of group therapy with multiply traumatized women is limited. Four studies of an interpersonal approach to group therapy with adult female incest survivors found improvements at termination in general psychological distress, depression, self-esteem, self-control, and some trauma-related symptoms, in both short-term (20, 26, 27) and long-term (19) formats. Improvements were greater for those subjects who perceived other group members as having had similar experiences. These studies, however, lacked a control group, a follow-up assessment, or both.

In an important study, Resick et al. (28) found that group therapy using a cognitive processing model resulted in significant improvement in both PTSD and depressive symptoms as compared to wait-list control groups. Though the subjects of Resick et al. consisted of adult rape victims without a history of childhood sexual abuse, their study demonstrated the possibility, in at least one trauma population, that group treatment may be effective in reducing core PTSD symptoms as well as problems with self-esteem and interpersonal relationships.

In the present study, we attempted to apply elements of effective PTSD treatment in a group therapy format designed for multiply traumatized and chronically ill women. This approach, named interactive psychoeducational group therapy (29), attempts to achieve significant reductions in the core PTSD symptoms in addition to providing benefits of increased hopefulness, self-esteem, and interpersonal skills. This trauma-focused group therapy embeds components from other established treatment approaches, including direct therapeutic exposure and cognitive-behavioral approaches (21, 30, 31), in which group support, instillation of hope, interpersonal learning, and universality are emphasized (32). Psychoeducational and cognitive-behavioral interventions are used to maintain the focus on the women’s adaptational strategies in response to the experience of being traumatized rather than on the relationships among group members. We hypothesized that symptomatic relief would occur as the women’s ability to gain perspective on their traumatic experiences increased, allowing trauma schemata to be integrated with and modified by their prior undistorted self-schemata (21).

In the present study, we attempted to measure the efficacy of this group therapy model with five groups (total N=29) of multiply traumatized women, based on assessments at baseline, at 1-month intervals during treatment, at termination, and at 6-month follow-up. Because no control group was available, the results of this study must be considered preliminary.

METHOD

Subjects

We recruited female subjects from the community through advertisements and referrals from area agencies. Subjects were first screened by telephone contact and then assigned for an initial psychiatric evaluation to assess their appropriateness for participation. Selection criteria included 1) age from 18 to 65 years; 2) victims or witnesses of violent crime, physical or sexual assault, or other emotionally traumatizing incidents (defined as serious threats to life or bodily integrity) in both childhood and adulthood; and 3) willingness to participate in a group modality. Exclusion criteria included 1) state of acute crisis, 2) active abuse of substances, 3) psychosis, 4) current suicidality, or 5) participation in another group therapy. We accepted subjects on the condition that they would make no changes in current treatment arrangements (i.e., individual therapy, medications, 12-step programs). No fees were charged or payments made to subjects.

For this study, we evaluated 56 subjects. We accepted into the study the 38 women who met inclusion criteria and formed groups of six or seven subjects each. Written informed consent was obtained from subjects after the purpose and procedures of the study were fully explained. Five subjects dropped out during the 2–3-week waiting period. Of the 33 subjects entering the study, 29 completed treatment. Four dropped out during phase 1 (one from each of the first four groups).

Therapists

The first author (H.L.), a female psychiatrist and developer of the treatment model, served as the lead therapist for all five groups. Her co-leaders were a female clinical psychologist (M.L.) for four groups, and a female psychiatrist for one group; both had been trained in the treatment model before initiation of the study. All three therapists had had several years of previous PTSD group therapy experience. The lead therapist monitored adherence to the treatment model in supervision sessions immediately following each group session. All therapists were blind to the quantitative assessment data collected by research assistants.

Group Therapy Procedure

Each group met for 90-minute sessions once a week over 16 consecutive weeks. Each session consisted of a brief psychoeducational lecture (about 15 minutes), followed by an interactive discussion directed by the therapists (about 1 hour) and then a wrap-up with an educational emphasis (about 15 minutes). Subjects were given booklets summarizing the series of lectures; at the end of each session, homework was assigned. The therapists used a blackboard to highlight essential points in the lectures.

The interactive psychoeducational group therapy model is divided into three treatment phases, each with a distinct focus. The aim of the first phase is to explore the effects of the trauma on the individual’s sense of self, particularly the issues of shame, trust, and disturbances in feminine identity. During this phase, each subject reviewed her traumatic events with the group and received feedback from group members and the therapists. The aim of the second phase is to explore the effects of the trauma on the individual’s interpersonal relationships, such as difficulties with intimacy, dependency, and sexual dysfunction. The lectures during this phase were centered on identifying maladaptive coping strategies and defense mechanisms that interfered with these relationships. The aim of the third phase is to explore the ways of finding meaning in one’s life despite the trauma. Lectures highlighted existential challenges that hinder ways of finding meaning, focused on ways to transform the traumatic experiences, and reviewed the importance of social support. We used interpersonal interactions to demonstrate to members how past traumatic schemata were reenacted in the present. A more detailed description of this treatment modality is available (29).

Measures

Four trained clinician-interviewers administered the study measures to subjects at baseline, 1-month intervals during treatment, termination, and 6-month follow-up. Each subject had the same interviewer for all assessments. This evaluation included a detailed review of trauma history and an assessment of PTSD and general psychiatric symptoms. General psychiatric diagnoses were determined by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Patient Version (34), incorporating the PTSD module developed for the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study (34), and the Structured Interview for Disorders of Extreme Stress (15).

PTSD measures

The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale assesses the frequency and intensity of the 17 PTSD symptoms listed in DSM-III-R for both current (i.e., within the past week) and lifetime periods. Test-retest and interrater reliabilities are adequate (35). This instrument has the advantage of being less reliant on the subject’s self-report, allowing the clinician-rater to probe the relevant symptoms in greater detail. In addition to the assessments at entry, termination, and follow-up, we administered the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale to subjects at 1-month, 2-month, and 3-month time points during the treatment course. The Civilian Mississippi Scale is a 39-item self-report questionnaire, adapted from the Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related PTSD by the original authors (36). It is a 5-point Likert scale consisting of questions about nightmares, avoidance of feelings about and reminders of the past, and suicidal and homicidal ideation. The Impact of Event Scale is a 15-item scale that consists of two subscales: cognitive intrusion and avoidance. Internal consistency of the subscales has been reported to be adequate (coefficient alpha=0.78 for intrusion and 0.80 for avoidance; split-half reliability for the total score was 0.86) (37).

Measures of psychiatric symptoms

The SCL-90-R is a 90-item Likert scale covering a broad spectrum of psychiatric symptoms. Derogatis (38) has reported acceptable test-retest reliability, internal consistency, and both concurrent and discriminant validity for the scale. The Beck Depression Inventory is a 21-item self-report questionnaire (39) that has been widely used in empirical research on depression in rape victims (22, 28, 40). The Dissociative Experiences Scale is a 28-item self-report scale that measures dissociative symptoms and experiences. Subjects mark a line to estimate the frequency of each event. Bernstein and Putnam (41) demonstrated that the scale has good reliability and validity.

Data Analysis

The analytic strategy consisted of two parts: first, examination of changes in outcome measures from pre- to posttreatment; and second, examination of changes between completion of treatment and 6-month follow-up. We used repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) or t tests to determine overall main effects of treatment on dependent variables as well as to examine effects of each independent variable (cohort, current age, age at traumas, type of trauma, type of perpetrator, recency of trauma, education, or marital status). We used median splits for noncategorical variables. Because of multiple comparisons, the p value was set at 0.01.

RESULTS

Demographic Characteristics

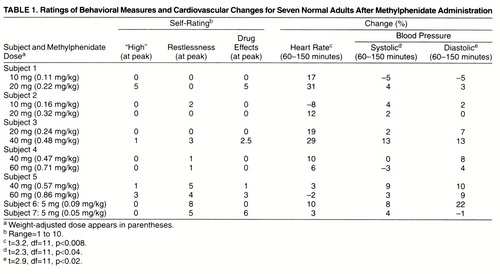

Demographic data reveal that the subjects, whose mean age was 41 years, were primarily Caucasian, relatively well educated, and partially employed (table 1). These subjects generally had experienced several traumas from childhood through adulthood: sexual assault or rape (83%), physical assault (59%), and violent accidents (31%). Perpetrators were usually family members (66%) and, less often, acquaintances (24%) or strangers (10%). On average, their last traumas were not recent.

The subjects had remained severely ill for an extended length of time. On average, each subject met criteria for three DSM-III-R diagnoses, including anxiety disorder (66%), mood disorder (52%), borderline personality disorder (34%), somatoform disorder (14%), and disorders of extreme stress (79%). About half had been hospitalized, had attempted suicide, or both. Their average score on the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale was 55 (SD=7.42). The women had been in outpatient psychotherapy for an average of 7.6 years (SD=3.4) before entry into the study; during the study, 83% were in individual therapy, and 79% were taking psychotropic medication (antipsychotics, 17%; antidepressants, 62%; antianxiety medications, 55%).

Effects

Pre- to posttreatment effects

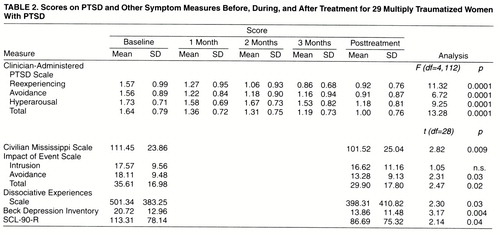

Table 2 lists the main results of the study. Subjects demonstrated significant reductions in their PTSD symptoms, as measured by all subscales of the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale, as well as in their total symptoms (26 of 29 subjects improved). These reductions were evident within the first month of treatment, and the subjects continued to show improvement through termination of treatment. Clinically meaningful reductions (more than one standard deviation below pretreatment levels, about a 50% reduction) in scores on the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale occurred for 38% of the group.

The self-report measures of PTSD (Civilian Mississippi Scale and Impact of Event Scale) showed less robust reductions. Subjects showed significant reductions in depressive symptoms and near-significant reductions for improvement in overall psychiatric and dissociative symptoms, as measured by SCL-90-R and the Dissociative Experiences Scale, respectively.

Effects of independent variables

On repeated measures ANOVAs, we found no differences in outcome between subgroups differing in current age, age at time of traumas, type of trauma, type of perpetrator, recency of trauma, education, or marital status.

Follow-up Assessment

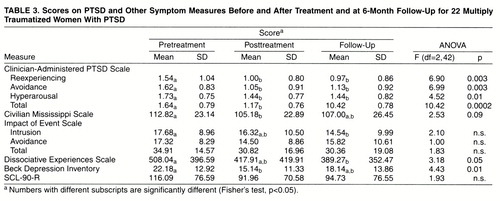

Table 3 presents the data for the 22 subjects who completed the follow-up evaluation 6 months after termination of treatment. The seven women who did not complete the follow-up evaluation did not significantly differ from the remaining subjects on any dependent measure at entry. Overall, the data indicate that subjects maintained their gains on the PTSD symptoms and showed some return toward baseline in symptoms of depression and psychiatric distress. At follow-up, in comparison to entry, the subjects showed significant reductions in their total score and all three subscale scores on the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale as well as in their scores on the Impact of Event Scale intrusion subscale, and on the Dissociative Experiences Scale. Half of the group showed clinically meaningful reductions (i.e., one standard deviation lower) in their scores on the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale.

Course of Illness

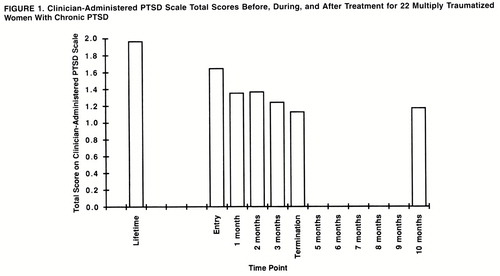

The larger context of course of illness and the impact of treatment can be gleaned by comparing these data with the Lifetime Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale, which, presumably, is a measure of subjects’ PTSD at its worst (usually several years before treatment). Figure 1 illustrates this relation. In comparison to the condition of PTSD at its worst (lifetime), subjects had shown some improvement by the time they entered the study (approximately 17% reduction overall). The 16-week group therapy program produced another 27% reduction in these symptoms, followed by a 3% increase at 6 months.

DISCUSSION

This study, even with the 6-month follow-up, is limited by the absence of a control or comparison group; therefore, these results must be viewed as preliminary, since it is not possible to determine whether another type of treatment might have been as effective. Possible explanations other than treatment effect for the positive outcomes include 1) Hawthorne effect, 2) regression to the mean, 3) effects of concurrent individual and psychopharmacologic treatments, and 4) rater bias. The subjects in this group, however, had been suffering from stable levels of PTSD symptoms despite multiple forms of treatment for many years before this study. They made no changes in their concurrent treatments during the study; thus, it is unlikely that they entered the study with high expectations, at especially difficult times, or in the midst of changes in their ongoing treatment regimens. We addressed rater bias during training and made every effort to minimize it through separation of treatment and assessment components. Thus, raters had no knowledge of subjects’ treatment experience.

The main results of this study show that this form of group therapy was consistently effective, across five cohorts of women, in reducing core PTSD symptoms and, secondarily, in diminishing the levels of psychiatric distress. These gains were largely retained at 6-month follow-up. The fact that gains were more prominent for PTSD symptoms than for general psychiatric symptoms is strongly suggestive of a specific treatment effect. Improvement was stronger on the clinician-administered instrument, which probed for more details of symptoms, than on the self-report measures, which had less specificity. Gains were equally evident among subjects varying in age, type and recency of trauma, type of perpetrator, level of education, and marital status, suggesting that the treatment may have applicability to a wide range of trauma populations.

These results are particularly encouraging in light of the severity of illness (e.g., extent of trauma, prior hospitalizations, high comorbidity) and treatment resistance (e.g., years of prior treatment) evident in this group. The psychoeducational format and active guidance of the therapists may have heightened the treatment effects by redirecting the members’ attention away from potentially complex interpersonal dynamics. Groups varied in the degree of their apparent cohesion and member-to-member intimacy, and although we used no group process measures to assess these variables, it is our belief that this treatment approach may be less dependent than other approaches on a high level of group cohesion for its therapeutic effect. Such questions might be addressed in further studies.

For multiply traumatized women with a long treatment history and chronic symptoms, a group approach such as the one studied here may offer relief for PTSD symptoms in a relatively brief and cost-effective manner. This line of research suggests that group therapies with a more structured, psychoeducational format may show efficacy in symptom reduction. Thus, the role of group therapy in PTSD treatment should not be prematurely restricted to addressing self-esteem and interpersonal dimensions of the illness.

Received June 10, 1997; revisions received Oct. 29, 1997, and Feb. 4, 1998; accepted Feb. 26, 1998. From the Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn.. Address reprint requests to Dr. Lubin, Post Traumatic Stress Center, 19 Edwards St., New Haven, CT 06511. The authors thank the National Center for PTSD, VA Medical Center, West Haven, Conn., for its support; and Cheryl Cottrol, M.D., and members of the Women’s Trauma Program research team for their participation in this study.

|

|

|

1. Breslau N, Davis G, Andreski M, Peterson E: Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:216–222Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Burgess AW, Groth AN, Holmstrom LL: Sexual Assault of Children and Adolescents. Lexington, Mass, DC Heath, 1978Google Scholar

3. Burnam MA, Stein JA, Golding JM, Sorenson SB, Forsyth AB, Telles CA: Sexual assault and mental disorders in a community population. J Consult Clin Psychol 1988; 56:843–850Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Russell DE: Sexual Exploitation: Rape, Child Sexual Abuse and Workplace Harassment. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage Publications, 1984Google Scholar

5. Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS: Posttraumatic stress disorder associated with exposure to criminal victimization in clinical and community population, in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: DSM-IV and Beyond. Edited by Davidson JR, Foa EB. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993, pp 113–143Google Scholar

6. Browne A, Finkelhor D: Impact of child sexual abuse: a review of the research. Psychol Bull 1986; 99:66–77Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Goodwin JM: Posttraumatic symptoms in incest victims, in Post Traumatic Stress Disorder in Children. Edited by Eth S, Pynoos RS. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1985, pp 81–102Google Scholar

8. Pribor E, Dinwiddie S: Psychiatric correlates of incest in childhood. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:52–56Link, Google Scholar

9. Rowan BA, Foy DW: Posttraumatic stress disorder in child sexual abuse survivors: a literature review. J Trauma Stress 1993; 6:3–20Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Herman J, Perry J, van der Kolk B: Childhood trauma in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146:490–495Link, Google Scholar

11. Ludolph PS, Westen D, Misle BA, Jackson A, Wixom J, Wiss F: The borderline diagnosis in adolescents: symptoms and developmental history. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:470–476Link, Google Scholar

12. Ogata SN, Silk KR, Goodrich S, Lohr N, Westen D: Childhood and sexual abuse in adult inpatients with borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:1008–1013Link, Google Scholar

13. Zanarini MC, Gunderson JG, Marino MF, Schwartz E, Frankenburg F: Childhood experiences of borderline patients. Compr Psychiatry 1989; 30:18–25Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Herman J: Complex PTSD: a syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated trauma. J Trauma Stress 1992; 5:377–391Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Pelcovitz D, van der Kolk B, Roth S, Mandel F, Kaplan S, Resick P: Development of a criteria set and a structured interview for disorders of extreme stress. J Trauma Stress 1997; 10:3–16Medline, Google Scholar

16. Herman J: Trauma and Recovery. New York, Basic Books, 1992Google Scholar

17. Cole C, Barney E: Safeguards and the therapeutic window: a group treatment strategy for adult incest survivors. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1987; 57:601–609Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Goodman B, Nowak-Scibelli D: Group treatment for women incestuously abused as children. Int J Group Psychother 1985; 35:531–544Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Hazzard A, Rogers JH, Angert L: Factors affecting group therapy outcome for adult sexual abuse survivors. Int J Group Psychother 1993; 43:453–468Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Herman J, Schatzow E: Time limited group therapy for women with history of incest. Int J Group Psychother 1984; 34:605–616Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Resick PA, Schnicke MK: Cognitive Processing Therapy for Rape Victims. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage Publications, 1993Google Scholar

22. Foa EB, Rothbaum OB, Riggs DS, Murdock TB: Treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder in rape victims: a comparison between cognitive-behavioral procedure and counseling. J Consult Clin Psychol 1991; 59:715–723Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Frank E, Anderson B, Steward BD, Dancu C, Hughes C, West D: Efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy and systematic desensitization in the treatment of rape trauma. Behavior Therapy 1988; 19:403–420Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Shalev AY, Bonne O, Eth S: Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: a review. Psychosom Med 1996; 58:165–182Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Solomon SD, Gerrity ET, Muff AM: Efficacy of treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder: an empirical review. JAMA 1992; 268:633–638Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Alexander P, Neimeyer R, Follete V, Moore M, Harter S: A comparison of group therapy treatment of women sexually abused as children. J Consult Clin Psychol 1989; 57:479–483Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Neimeyer R, Harter S, Alexander P: Group perceptions as predictors of outcome in the treatment of incest survivors. Psychiatr Res 1991; 1:148–158Google Scholar

28. Resick PA, Jordan CG, Girelli SA, Hutter CK, Marhoefer-Dvorak S: A comparative outcome study of behavioral group therapy for sexual assault victims. Behavior Therapy 1989; 19:385–401Crossref, Google Scholar

29. Lubin H, Johnson DR: Group therapy for traumatized women. Int J Group Psychother 1997; 47:271–290Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Schwartz RA, Prout MF: Integrative approaches in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychotherapy 1991; 28:364–373Crossref, Google Scholar

31. Veronen LJ, Kilpatrick DG: Stress management for rape victims, in Stress Reduction and Prevention. Edited by Meichenbaum D, Jaremko ME. New York, Plenum Press, 1983, pp 341–374Google Scholar

32. Yalom ID: The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy, 2nd ed. New York, Basic Books, 1976Google Scholar

33. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Patient Version 1.0 (SCID-P). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

34. Kulka RA, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, Hough RL, Jordan BK, Marmar CR, Weiss DS: National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study Report (NVVRS): Description, Current Status, and Initial Prevalence Estimates. Washington, DC, Veterans Administration, 1988Google Scholar

35. Blake DD, Weathers F, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Klauminzer G, Charney DC, Keane TM: The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. J Trauma Stress 1995; 8:75–90Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Keane TM, Caddell JM, Taylor KL: Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: three studies in reliability and validity. J Consult Clin Psychol 1988; 56:85–90Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Horowitz MJ, Wilner N, Alvarez W: Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med 1979; 41:209–218Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Derogatis LR: SCL-90-R: Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual, I, for the Revised Version. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University, Clinical Psychometrics Research Unit, 1977Google Scholar

39. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J: An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961; 4:561–571Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Atkeson BM, Calhoun KS, Resick PA, Ellis EM: Victims of rape: repeated assessment of depressive symptoms. J Consult Clin Psychol 1982; 50:96–102Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Bernstein EM, Putnam FW: Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale. J Nerv Ment Dis 1986; 174:727–735Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar