Effects of Group Treatment for Women With a History of Childhood Sexual Abuse

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Empirical support for the effectiveness of group therapies for women with a history of childhood sexual abuse is scant. This study examined the feasibility of conducting abuse-focused research and group treatment on a short-term unit and evaluated the effectiveness of the Women's Safety in Recovery group. METHODS: Eighty-six women with a history of childhood sexual abuse participated in treatment as usual (N=38) or in the Women's Safety in Recovery group (N=48). The latter group met three times weekly for one hour, focusing on patients' current safety and self-care. Participants completed the Symptom Checklist—Revised at baseline, discharge, and six-month follow-up. Patients rated their experience in treatment at discharge and six-month follow-up, and therapists rated patients' treatment experiences at discharge. The feasibility of the treatment group was measured by enrollment rates, group attendance, and attrition. RESULTS: Eighty-two percent of eligible patients agreed to enroll in the study. Women's Safety in Recovery participants attended an average of ten group meetings. Seventy percent of enrollees completed discharge assessments, and of these, 82 percent completed the six-month follow-up. Compared with treatment-as-usual patients, Women's Safety in Recovery participants reported greater symptom improvement and reported that their childhood sexual abuse issues had been more thoroughly addressed. These differences were present at discharge and at six-month follow-up. Therapists also perceived that abuse issues of these participants had been more thoroughly addressed. CONCLUSIONS: Women's Safety in Recovery participants reported significant reductions in distress compared with those receiving treatment as usual. The abuse-focused research program and the Women's Safety in Recovery group proved feasible, despite attrition.

Childhood sexual abuse is highly prevalent among adult psychiatric patients (1,2,3), as are psychological sequelae (4,5). Despite extensive clinical literature on abuse-focused treatments, little research has been done on their effectiveness. Group therapies have been described as effective for reducing psychiatric distress (6,7,8), including the stigma and shame that frequently follow sexual victimization (9,10).

Despite the purported benefits of group treatments for childhood sexual abuse (6,7,8,11), we are aware of only two controlled treatment studies (12,13) and a few uncontrolled trials (14,15,16), all of which reported beneficial effects with outpatients. This paper describes a group therapy model for hospitalized patients, Women's Safety in Recovery, and reports results of a study of its effectiveness compared with treatment as usual.

Both risks and benefits of including acutely ill patients in abuse-focused group treatments must be carefully considered (6,7,17). In this preliminary investigation, we examined the feasibility of conducting an abuse-focused research program and group treatment on a short-term inpatient unit, and we evaluated the effectiveness of the Women's Safety in Recovery model. Feasibility was operationally defined as elective enrollment in the research study, attendance in the group, and completion of the research study.

Two hypotheses guided the research. First, we hypothesized that participants in the Women's Safety in Recovery group would report more symptom improvement at six-month follow-up than treatment-as-usual participants. Second, we hypothesized that the effectiveness of the Women's Safety in Recovery treatment would be reflected both in patients' self-reports and in therapists' ratings of patient satisfaction with the treatment program, overall functioning, and the extent to which issues of childhood sexual abuse were addressed.

Methods

Participants

Eighty-six women with a history of childhood sexual abuse participated in either treatment as usual (N=38) or the specialized abuse-specific treatment (N=48) as an adjunct to routine care. To identify potential subjects, consecutive admissions to an integrated treatment unit, a combined inpatient unit and partial hospital program (18), were screened for histories of childhood sexual abuse. Of the 707 women screened in a two-year period, 312 (44 percent) reported childhood sexual abuse as defined below.

A total of 126 of the 312 women with a history of childhood sexual abuse (40 percent) met the study's eligibility criteria. To be eligible, a patient had to have an inpatient or partial hospital stay longer than five days, no florid psychosis or mania, and no mental retardation and had to agree to participate in routine unit activities. Of the eligible participants, only 23 patients (18 percent) declined enrollment in the research. Seventeen women were not enrolled due to the study's insufficient resources. Thus 86 women participated.

Because inpatients on the integrated treatment unit and patients in the partial hospital program participate in the same group program (18), inpatients continued in the research study after discharge to the partial hospital. Similarly, any patients in the partial hospital program who required hospitalization continued in the research study. The attending psychiatrist assigned psychiatric diagnoses at the time of the patient's discharge from the hospital.

Definition of sexual abuse

No consensus has emerged about the definition of childhood sexual abuse (19). In this study, it was defined as any sexual contact before age 18 with a family member five or more years older than the patient or unwanted sexual contact with a family member less than five years older, or any extrafamilial sexual contact that was unwanted. Sexual contact was defined as physical contact of a sexual nature, ranging from kissing and hugging to sexual intercourse.

Forty-nine of the 86 participants (57 percent) reported being victimized by more than one perpetrator. Among the 173 perpetrators, 33 (19 percent) were parents or parent figures (defined as a foster father or a mother's live-in boyfriend), 55 (32 percent) were other family members, and 85 (49 percent) were not family members. All participants reported at least one abuse incident involving contact with sexual organs, 48 (56 percent) reported experiencing vaginal or anal intercourse, and 41 (48 percent) reported that a perpetrator used physical force at least once. Thirty-two of the patients (37 percent) reported first abuse incidents before they were six years old, 29 (34 percent) between seven and 12 years, and 25 (29 percent) between 13 and 17 years. No statistically significant differences between the treatment-as-usual group and the Women's Safety in Recovery group were found on these variables.

Measures

Life Experiences Scale.

The Life Experiences Scale (LES) (2), adapted for this study, is a structured interview that covers a broad range of life events and yields detailed information about characteristics of childhood sexual abuse.

Symptom Checklist—Revised.

The Symptom Checklist—Revised (SCL-90-R) is a self-report measure that provides a general severity index of psychological distress and assesses nine primary symptom dimensions (20). Test-retest reliabilities ranging from .77 to .90 have been reported. Internal consistency reliabilities have ranged from .78 to .90.

Experience in treatment.

Both patients and their therapists responded to three items about treatment. One item asked about the degree to which "your issues regarding your history of sexual abuse" were addressed during treatment, with 1 indicating that they were not at all addressed, and 7 that they were thoroughly addressed. Another item asked about the patients' overall experience of the general treatment program, with 1 indicating poor and 7 extremely good. The therapist and the patient rated the patient's functioning on admission and at discharge on a scale from 1, very poor, to 7, excellent.

Design and procedure

A quasiexperimental (nonconcurrent) design (21) was employed. Treatment-as-usual patients were enrolled from July 1994 to June 1995, and Women's Safety in Recovery groups were conducted from September 1995 to September 1996. Given the nature of our setting and the pilot nature of our treatment, we used a quasiexperimental design to maximize the likelihood of determining the utility and feasibility of the intervention. Time in the group program was controlled and was equivalent in the treatment-as-usual group and the Women's Safety in Recovery group.

During the intake interview, primary therapists conducted brief screening interviews for childhood sexual abuse with every patient admitted to the inpatient unit or partial hospital (22). One of the unit-based investigators (NLT or RPH) invited patients who reported unwanted sexual contact before age 18 to participate in the research. The research was explained as a means to learn more about the relationships between patients' life experiences, psychological distress, and response to treatment. The Women's Safety in Recovery group was described as a group for women with a history of childhood sexual abuse that focused on current safety issues.

When informed consent was obtained, the LES and SCL-90-R were administered. At discharge and at six-month follow-up, the SCL-90-R was readministered, and patients were asked to rate their experience in treatment. Therapists rated patients' experience in treatment at discharge. Mean±SD length of follow-up was 216±34 days, or approximately seven months, after patients left the general treatment program.

Treatment as usual.

The integrated treatment unit program consisted of individual, group, family, and somatic therapies focused on crisis resolution and symptom reduction. Approximately 20 hours of group and activity therapies that applied cognitive, psychoeducational, and supportive approaches were offered each week. The group and activity therapies did not address sexual abuse issues.

Women's Safety in Recovery.

The Women's Safety in Recovery group was co-led by female and male therapists with master's-level training. The four leaders were full-time staff members who also functioned as primary therapists and leaders of other groups, including treatment-as-usual groups. Women attended the group three times a week for one hour in lieu of three other regularly scheduled groups (creative arts and health maintenance) in the general treatment program. The Women's Safety in Recovery curriculum contained material that was covered by the groups not attended. Material in the Women's Safety in Recovery group was tailored to women with a history of childhood sexual abuse.

A detailed description of the Women's Safety in Recovery treatment is available elsewhere (22). Briefly, the model is theoretically grounded in Herman's work (23) on first-stage trauma recovery groups, which use educational methods to focus on safety and self-care in the present. Psychoeducation about the possible effects of childhood sexual trauma in adulthood is emphasized, as are problem-solving and skill-building exercises to help patients identify deficits in self-care and develop strategies for improvement. Detailed disclosures about abuse histories are discouraged.

Each week of the three-week curriculum has a distinct focus on safety and control. Week 1 focuses on safety and control of the body; week 2, the environment (defined as persons and places); and week 3, the emotions. The group includes didactic presentations, problem-solving exercises, topic-focused discussions, art therapy exercises, and homework. Patients in the study joined the group at any point and were members only during their stay in the integrated treatment unit.

A treatment manual (available from the first author) detailed the material to be covered in each session. To ensure that standardized information was conveyed, group leaders completed checklists after each session that indicated whether the designated topics had been covered. The first and second authors met regularly with group leaders to ensure adherence to the protocol.

Data analyses

Change scores were computed from admission to discharge and from admission to six-month follow-up on the SCL-90-R and patients' ratings on the three variables about their experience in treatment. Repeated-measures analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) were conducted on change scores at discharge and at six-month follow-up for the two treatment groups—treatment as usual and Women's Safety in Recovery. Between-group ANCOVAs were conducted on therapists' ratings at discharge for the three variables measuring experience in treatment.

All analyses were adjusted for covariates that could contribute to outcome. The variables included high school education (dichotomous), marital status (dichotomous), active substance abuse (dichotomous), and length of stay (days). These variables have been associated with treatment response in group research with sexually abused women (14,24,25) and other populations (26,27). Analyses were adjusted for length of stay because differing amounts of exposure to the integrated treatment unit program could be related to outcome. We employed two-tailed significance tests at the .05 level. Each analysis included an examination of residuals as a check on the required assumptions of normally distributed errors with constant variance.

Results

Characteristics of participants

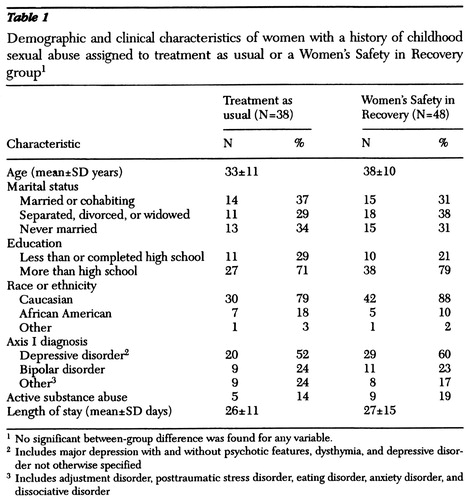

Table 1 presents demographic, diagnostic, and length-of-stay data for study participants. Patients in the two treatment groups were comparable on variables that can influence treatment response, including age, marital status, education, race or ethnicity, primary diagnosis, active substance abuse, and length of stay. No significant between-group differences were found for these variables.

Symptom improvement

Forty-three patients completed the six-month study, 22 in the treatment-as-usual group and 21 in the Women's Safety in Recovery group.

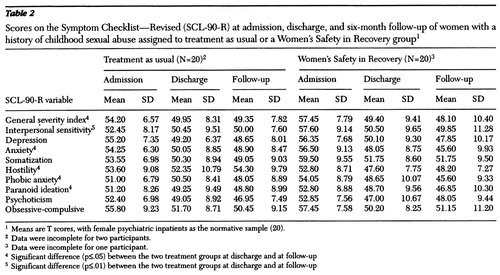

Table 2 presents mean scores and standard deviations on the SCL-90-R general severity index (GSI) and the nine subscales. The Women's Safety in Recovery group showed a significantly greater reduction on the GSI than the treatment-as-usual group (F=4.25, df=1,34, p=.05). Overall GSI effects were accounted for by decreases in scores on several subscales, including interpersonal sensitivity (F=6.97, df=1,34, p=.01), anxiety (F=4.42, df= 1,34, p=.04), hostility (F=4.46, df=1,34, p=.04), phobic anxiety (F=6.29, df=1,34, p=.02), and paranoid ideation (F=5.26, df=1,34, p=.03). A trend toward a decreased score on the somatization subscale was also noted (F=3.79, df=1,34, p=.06). No significant differences were found in scores on the depression, psychoticism, and obsessive-compulsive subscales. No significant group-by-time interactions on the GSI and subscales were found.

Experience in treatment

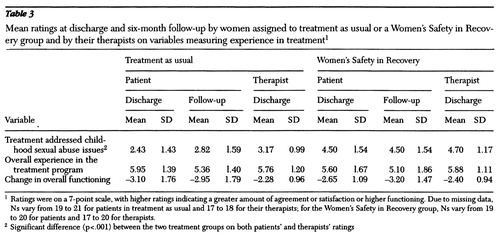

Mean ratings on the variables measuring experience in treatment are presented in Table 3. Participants in the Women's Safety in Recovery group reported that their childhood sexual abuse issues had been more thoroughly addressed than did control participants (F=17.22, df=1,35, p<.001). Similarly, therapists reported that the childhood sexual abuse issues of patients in the Women's Safety in Recovery group had been more thoroughly addressed (F=14.52, df=1,32, p<.001). No significant differences were found in patients' or therapists' ratings of patients' overall experience of the treatment program or change in overall functioning.

Feasibility

Because one aim of the study was to establish the feasibility of an inpatient-based, abuse-focused group treatment, we present detailed attrition data to clarify reasons for subjects' withdrawal from the research study.

Predischarge attrition.

Of the 86 women who enrolled in the study—38 in the control group and 48 in the Women's Safety in Recovery group—60 (70 percent) were included in the analyses of discharge assessment data, 29 from the control group and 31 from the Women's Safety in Recovery group. Thus nine women from the control group and 17 from the experimental group dropped out of the study before discharge.

This attrition may or may not be construed as reflecting an iatrogenic effect of the Women's Safety in Recovery group or of this study more generally. For 18 of the 26 women who dropped out before discharge, an iatrogenic effect was very unlikely. Twelve of these women (six in each group) were discharged with the approval of their treatment teams after a stay of fewer than 14 days on the integrated treatment unit. Further, three patients in the Women's Safety in Recovery group could not continue their participation due to unforeseen circumstances—one was transferred to jail and one to long-term care, and another experienced side effects from electroconvulsive therapy. Three other women in the Women's Safety in Recovery group did not receive discharge assessments because the study had insufficient resources. In sum, 18 of the 26 patients (69 percent) who did not complete the study withdrew for reasons that were unrelated to the intervention.

Three other patients withdrew for reasons that appeared unrelated to the intervention, but the exact determinants of withdrawal are unclear. These participants had unplanned discharges that were judged to be premature by the treatment teams—two from the control group and one from the Women's Safety in Recovery group.

An iatrogenic effect of the study might be suspected for five patients (6 percent of the sample of 86 women)—one from the control group and four from the Women's Safety in Recovery group. These patients withdrew from the study but remained in the general treatment program. The participant in the control group withdrew during the LES interview because she found the autobiographical material too upsetting, and four members of the Women's Safety in Recovery group dropped out because participation was causing distress and unwanted thoughts about their childhood abuse.

Postdischarge attrition.

Of the 60 women who completed discharge assessments, 43 (82 percent) completed the six-month follow-up—22 from the control group and 21 from the Women's Safety in Recovery group. Thus 17 patients did not participate in the follow-up (seven from the control group and ten from the experimental group), most often because they could not be reached by telephone or certified letter. Thus, of the 86 study enrollees, half (50 percent) completed the six-month follow-up.

We compared follow-up participants (N=43) and nonparticipants (N=17) on a number of variables that might influence long-term treatment response, including marital status, education, substance abuse, length of stay, and scores on the general severity index of the SCL-90-R at admission and discharge. In addition, four variables related to childhood sexual abuse were examined. Follow-up participants were more likely to have completed high school than nonparticipants (Fisher's exact test, p=.05). In addition, follow-up participants' general severity index scores at admission indicated less severity than the scores of nonparticipants (t=-2.39, df=56, p=.02). Other between-group differences were not significant.

Women's Safety in Recovery group attendance.

Among the 31 participants in the Women's Safety in Recovery group who completed the discharge assessment, the average number of group sessions attended was ten, the mode and median were nine, and the range was from four to 21 sessions.

Discussion and conclusions

This study represents an empirical attempt to examine the feasibility and effectiveness of a specialized group therapy for inpatients and partial hospital patients with a history of childhood sexual abuse. In our judgment, the abuse-focused research program and the Women's Safety in Recovery group proved feasible. Elective enrollment in the study was high—the great majority of patients who met eligibility requirements chose to participate. Nevertheless, many patients with a history of childhood sexual abuse did not meet other inclusion criteria.

Attendance in the Women's Safety in Recovery group was adequate. Attrition proved most problematic. Patients' brief lengths of stay on the inpatient and partial hospital unit led to an overall attrition rate of 30 percent before discharge. Nevertheless, most of the patients who did not complete the study were discharged early by their treatment teams, and no iatrogenic effects of their participation were suspected.

The first hypothesis of the study—that participants in the Women's Safety in Recovery group would report more symptom improvement at six-month follow-up than treatment-as-usual participants—was supported. Patients in the Women's Safety in Recovery group reported greater symptom improvement on the SCL-90-R than treatment-as-usual participants. These significant between-group differences were present at discharge and were sustained at the six-month follow-up.

The second hypothesis was that the effectiveness of the Women's Safety in Recovery treatment would be reflected both in patients' and therapists' ratings of patients' satisfaction with the treatment program, overall functioning, and the extent to which issues of childhood sexual abuse were addressed. This hypothesis received partial support. Compared with women in the control group, Women's Safety in Recovery participants and their therapists reported that issues of childhood sexual abuse had been more thoroughly addressed. Despite greater and more sustained improvement of Women's Safety in Recovery participants, participants in both the experimental and control groups reported comparable levels of satisfaction with the overall treatment program, and the change scores for global functioning were similar.

Moreover, the therapists' ratings of patients' overall experience in the treatment program and global change in functioning did not differ between groups. Expectancy effects (that is, bias stemming from therapists' expectations that patients in the experimental condition would show more improvement) are therefore unlikely to have contributed substantially to differences between groups. In sum, the overall sustained reduction of symptomatic distress among participants in the Women's Safety in Recovery group may support the specificity and potential long-term benefits of this intervention.

Strengths of this study include its application of an abuse-focused treatment with an acutely ill patient population, detailed documentation of childhood sexual abuse histories through a preliminary screening and a structured interview, use of a standardized measure for assessing symptom change, development of a manual for the intervention, and consideration of feasibility issues.

Several directions for future research should be considered. First, with respect to attrition, patient characteristics that predict attendance, attrition, and outcome must be assessed (28), and outcomes for those who do not complete treatment should be evaluated. Decreasing attrition at six-month follow-up through more extensive outreach and patient tracking may yield important information about treatment effectiveness.

Second, turning to measurement issues, data on behavioral outcomes such as health care utilization, quality and stability of social supports, and revictimization experiences would provide important information about the impact of the Women's Safety in Recovery intervention. Moreover, components of the curriculum should be evaluated to determine which are more or less effective. Specifically, the therapeutic benefit of addressing issues related to childhood sexual abuse could be compared with the benefit derived from other content areas of the curriculum.

Third, a randomized controlled trial of the Women's Safety in Recovery model would constitute a more stringent test of this treatment. Randomization has traditionally represented the gold standard in clinical trials, although rigid adherence to randomization in clinical research has been criticized as ignoring potential ethical violations, leading to higher study costs, and limiting generalizability to nonlaboratory settings (29). In our study some patients randomly assigned to the treatment-as-usual group might have chosen to be included in the Women's Safety in Recovery group. Not allowing them a choice may have had negative consequences for individual patients and for the general treatment program.

Finally, this model has been used exclusively with women, and primarily with people suffering from mood disorders. Modifications might be required for mixed-gender groups or men's groups and for people with other principal axis I disorders.

Addressing these methodological issues will lead to more precise information about who benefits from Women's Safety in Recovery treatment and why. In the meantime, it appears that the Women's Safety in Recovery model is a feasible and effective treatment for hospitalized women who report a history of childhood sexual abuse.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Larry Seidlitz, Ph.D., for his comments on portions of this paper, as well as Sue Cyrulik, M.S., N.P.P., Ann Betz, C.S.W.R., C.G.P., Miriam Barkun, C.S.W., and Tom Milliman, Ms.Ed., for their help in conducting groups. Preparation of this article was partly supported by a Gottschalk research grant from the Mental Health Association of Monroe County, New York; a Leonard F. Salzman research award from the department of psychiatry at the University of Rochester; and grants K07-MHO1135 and R01-MH39531 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, 300 Crittenden Boulevard, Rochester, New York 14642-8409 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Talbot and Dr. Houghtalen are assistant professors of psychiatry, Dr. Duberstein is assistant professor of psychiatry and oncology, Dr. Cox is professor of biostatistics and psychiatry, Dr. Giles is professor of psychiatry and neurology, and Dr. Wynne is professor of psychiatry.

|

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of women with a history of childhood sexual abuse assigned to treatment as usual or a Women's Safety in Recovery group1

1 No significant between-group difference was found for any variable.

2 Includes major depression with and without psychotic features, dysthymia, and depressive disorder not otherwise specified

3 Includes adjustment disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, eating disorder, anxiety disorder, and dissociative disorder

|

Table 2. Scores on the Symptom Checklist—Revised (SCL-90-R) at admission, discharge, and six-month follow-up of women with a history of childhood sexual abuse assigned to treatment as usual or a Women's Safety in Recovery group1

1 Means are T scores, with female psychiatric inpatients as the normative sample (20).

2 Data were incomplete for two participants.

3 Data were incomplete for one participant.

4 Significant difference (p≤.05) between the two treatment groups at discharge and at follow-up

5 Significant difference (p≤.01) between the two treatment groups at discharge and at follow-up

|

Table 3. Mean ratings at discharge and six-month follow-up by women assigned to treatment as usual or a Women's Safety in Recovery group and by their therapists on variables measuring experience in treatment1

1 Ratings were on a 7-point scale, with higher ratings indicating a greater amount of agreement or satisfaction or higher functioning. Due to missing data, Ns vary from 19 to 21 for patients in treatment as usual and 17 to 18 for their therapists; for the Women's Safety in Recovery group, Ns vary from 19 to 20 for patients and 17 to 20 for therapists.

2 Significant difference (p<.001) between the two treatment groups on both patients' and therapists' ratings

1. Briere J, Zaidi L: Sexual histories and sequelae in female psychiatric emergency room patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 146:1602-1606, 1989Link, Google Scholar

2. Bryer J, Nelson B, Miller J, et al: Childhood sexual and physical abuse as factors in adult psychiatric illness. American Journal of Psychiatry 144:1426-1430, 1987Link, Google Scholar

3. Lipschitz DS, Kaplan ML, Sorkenn JB, et al: Prevalence and characteristics of physical and sexual abuse among psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatric Services 47:189-191, 1996Link, Google Scholar

4. Browne A, Finkelhor D: Impact of child sexual abuse: a review of the research. Psychological Bulletin 99:66-77, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Polusny MA, Follette VM: Long-term correlates of child sexual abuse: theory and review of the empirical literature. Applied and Preventative Psychology 4:143-166, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Briere J: Therapy for Adults Molested as Children: Beyond Survival. New York, Springer, 1996Google Scholar

7. Courtois CA: Healing the Incest Wound. New York, Norton, 1988Google Scholar

8. Herman JL, Schatzow E: Time-limited group therapy for women with a history of incest. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy 34:605-615, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Feiring C, Taska L, Lewis M: A process model for understanding adaptation to sexual abuse: the role of shame in defining stigmatization. Child Abuse and Neglect 20:767-782, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Talbot NL: Women sexually abused as children: the centrality of shame issues and treatment implications. Psychotherapy 33:11-18, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Van der Kolk BA: The role of the group in the origin and resolution of the trauma response, in Psychological Trauma. Edited by Van der Kolk BA. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1987Google Scholar

12. Alexander PC, Neimeyer RA, Follete VM, et al: A comparison of group treatments of women sexually abused as children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 57:479-483, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Zlotnick C, Shea TM, Rosen K, et al: An affect-management group for women with posttraumatic stress disorder and histories of childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Traumatic Stress 10:425-436, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

14. Carver C, Stalker C, Stewart E, et al: The impact of group therapy for adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 34:753-758, 1989Medline, Google Scholar

15. Fisher PM, Winne PH, Ley RG: Group therapy for adult women survivors of child sexual abuse: differentiation of completers from drop-outs. Psychotherapy 30:616-624, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Hazzard A, Rogers JH, Angert L: Factors affecting group therapy outcome for adult sexual abuse survivors. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy 43:453-468, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Cole CH, Barney EE: Safeguards and the therapeutic window: a group treatment strategy for adult incest survivors. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 57:601-609, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Houghtalen RP, Talbot NL: A combined inpatient and partial hospital program. Psychiatric Services 48:242-244, 1997Link, Google Scholar

19. Briere J: Methodological issues in the study of sexual abuse effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 60:196-203, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Derogatis LR: The SCL-90-R Manual II: Administration, Scoring, and Procedures. Towson, Md, Clinical Psychometric Research, 1983Google Scholar

21. Kazdin AE: Research Design in Clinical Psychology. New York, Harper & Row, 1980Google Scholar

22. Talbot NL, Houghtalen RP, Cyrulik S, et al: Women's Safety in Recovery: group therapy for patients with a history of childhood sexual abuse. Psychiatric Services 49:213-217, 1998Link, Google Scholar

23. Herman JL: Trauma and Recovery. New York, Basic Books, 1992Google Scholar

24. Fisher PM, Winne PH, Ley RG: Group therapy for adult women survivors of child sexual abuse: differentiation of completers from drop-outs. Psychotherapy 30:616-624, 1983Crossref, Google Scholar

25. Follette VM, Alexander DC, Follette WC: Individual predictors of outcome in group treatment for incest survivors. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 59:150-155, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Baekeland F, Lundwall L: Dropping out of treatment: a critical review. Psychological Bulletin 82:738-783, 1975Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. MacNair RR, Corazzini JG: Client factors influencing group therapy dropout. Psychotherapy 31:352-362, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Chambless DL, Hollon SD: Defining empirically supported therapies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 66:7-18, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Cronbach LJ, Ambron SR, Dornbusch SM, et al: Toward Reform of Program Evaluation. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 1980Google Scholar