Access to Specialty Mental Health Services Among Women in California

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The Anderson behavioral model was used to investigate racial and ethnic disparities in access to specialty mental health services among women in California as well as factors that might account for such disparities. METHODS: The study was a cross-sectional examination of a probability sample of 3,750 California women. The main indicators of access to services were perceived need, service seeking, and service use. Multivariate models were constructed that accounted for need and enabling and demographic variables. RESULTS: Significant racial and ethnic variations in access to specialty mental health services were observed. African-American, Hispanic, and Asian women were significantly less likely to use specialty mental health services than white women. Multivariate analyses showed that Hispanic and Asian women were less likely than white women to report perceived need, even after frequent mental distress had been taken into account. Among women with perceived need, African-American and Asian women were less likely than white women to seek mental health services after differences in insurance status had been taken into account. Among women who sought services, Hispanic women were less likely than white women to obtain services after adjustment for the effects of poverty. Need and enabling factors did not entirely account for the observed disparities in access to services. CONCLUSIONS: Additional research is needed to identify gender- and culture-specific models for access to mental health services in order to decrease disparities in access. Factors such as perceived need and decisions to seek services are important factors that should be emphasized in future studies.

Racial and ethnic disparities in mental health care are gaining increasing national attention (1). A number of studies have documented different patterns of use of specialty mental health services among whites, African Americans, Latinos, and Asian Americans (2,3,4), with nonwhites using significantly fewer services.

As noted by Alegria and colleagues (3), racial differences in the rates of use of specialty mental health services do not necessarily indicate disparities in access to care. Such research has demonstrated the necessity of adjusting for true need for services as well as for social environmental factors, such as poverty. Patients who are not white appear to use fewer services relative to their clinical indications of need compared with white patients (2), and although racial and ethnic variations in the use of specialty mental health services are linked to economic and social context—factors such as living in a poverty area, being poor, and being uninsured (3,4,5)—these factors do not fully account for observed differences in utilization.

In this study we investigated factors that could account for racial and ethnic disparities in access to specialty mental health services by examining service use in conjunction with perceived need and service-seeking behaviors.

The Anderson behavioral model (6) defines disparities, or inequitable access, as conditions under which social factors (such as ethnicity) and enabling variables (such as income) are major predictors of service use. Under equitable conditions, need (such as mental health status) and demographic factors should account for the most variance in use of services. However, culture or ethnicity, conceptualized as a social factor in this model, may interact with each of these factors, yielding significant racial and ethnic differences in utilization rates that may or may not have a basis in inequity.

For example, cultural differences appear to affect perceived need for services and preferences for treatment that focuses on mental—to the exclusion of physical—health. Asian Americans may underutilize specialty mental health services, because many Asian cultures do not distinguish psychological from somatic distress, and patients from these cultures may encounter a lack of correspondence between cultural and mainstream medical conceptualizations of psychiatric disorders and their treatment (7). The extent to which observed racial and ethnic disparities in the use of specialty mental health services can be accounted for by variations in perceived need is not well understood. Research is needed that adjusts for cultural variation in the extent to which specialty mental health services are seen as a useful or appropriate means of dealing with psychological distress.

The behavioral model also focuses on patients' beliefs, experiences, and other conditions that influence the propensity to seek services in the presence of perceived need. In a reanalysis of data from the National Comorbidity Survey, Diala and colleagues (8,9) examined African-American men's and women's attitudes toward specialty mental health services. Before they used services, both African Americans in the general population and those with identified need had more positive attitudes toward service use than whites. Among those who used services, postutilization attitudes were significantly more negative than those of whites. Such research suggests the importance of examining racial and ethnic variations in service seeking among individuals who have a perceived need for services. Racial and ethnic variations at this stage of access to services could point to inequalities related to previous treatment experiences or other attitudes and beliefs about the potential availability or efficacy of mental health services.

Issues of women and gender have received little attention in research on racial and ethnic disparities in access to specialty mental health services. Attention to gender issues may be essential for understanding disparities in access to care. Women are more likely than men to use specialty mental health services (10). The factors associated with access to care differ by gender (11), and women may be especially vulnerable to enabling factors that function as racially linked disparities, such as low educational attainment and poverty (12). The purpose of the study reported here was to delineate any racial disparities in access to specialty mental health services, specifically among women. We addressed this research question by using a use a large probability sample of women living in California.

The study used the Anderson behavioral model to examine racial and ethnic variations in access to specialty mental health services. We used multiple indicators for access to services by examining racial and ethnic variation in perceived need, service seeking, and utilization. We accounted for psychological distress as a need factor and accounted for enabling factors such as education, poverty, and insurance status. The goal of the study was to examine potential disparities in access to mental health services at each phase of access—perceived need, service seeking (with perceived need taken into account), and utilization (with service seeking taken into account)—in an effort to better understand racially linked barriers to access to mental health services.

Methods

We used data from the 2001 California Women's Health Survey (CWHS), a population-based, random-digit-dial annual probability survey sponsored by the California Department of Health Services and designed in collaboration with several other state agencies and departments. Interviews for the CWHS are conducted in English or Spanish and take approximately 30 minutes to complete.

The response rate for the 2001 survey was 74 percent, yielding a sample of 4,018 women aged 18 years or older. More detailed information about the sampling procedures can be found elsewhere (13). The completion rate for women who consented to the interview was 93 percent, yielding a sample of 3,750 for this study. No significant differences in race or ethnicity were found between women who completed the survey and those who did not. However, the women who did not complete the interview were slightly older than those who completed it (χ2=53.5, df=3, p<.01).

Specialty mental health services were defined in a manner consistent with previous research (3): services delivered by a mental health professional, including a psychologist, a psychiatrist, a counselor, or a therapist. The women were asked whether they had wanted such services in the previous 12 months. Those who responded affirmatively were coded as positive for perceived need. Women who reported perceived need were then asked whether, in the previous 12 months, they had tried to obtain those services. Women who responded affirmatively were coded as positive for service seeking. Women who reported service seeking were then asked whether, in the previous 12 months, they had obtained the mental health services they reported wanting. Women who responded affirmatively were coded as positive for service utilization.

A measure of psychological distress was used as a proxy for need factors. The "frequent mental distress" variable from the "healthy days" measure (14) was used as a measure of general psychological distress. The healthy days measure is a reliable and valid set of four items developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that is widely used to assess health-related quality of life (15,16). Frequent mental distress is characterized by reports of at least 14 days of poor mental health ("including stress, depression, and problems with emotions") in the previous 30 days and is significantly associated with disability, health risk behaviors, and unemployment (14,17,18).

Race or ethnicity was determined on the basis of women's self-identification. We used a total of five racial and ethnic categories: white (55.4 percent of the sample), African American (6.2 percent), Hispanic (23.8 percent), Asian or Pacific Islander (11.8 percent), and Native American or other (2.7 percent). Age was entered into the analyses as a categorical variable: 18 to 29 years (18.8 percent), 30 to 44 years (35.6 percent), 45 to 64 years (29.3 percent), and 65 years or older (16.3 percent). Education was entered as a categorical variable: less than high school (13.7 percent); high school graduate (23.4 percent); some college, technical, or vocational training (30.6 percent); and college graduate and beyond (32.4 percent). Poverty was defined by using the federal poverty guidelines and was entered into the analyses as a dichotomous variable (19); 12.9 percent of the women were living below the federal poverty level. Women were coded as insured (85.8 percent) if they reported health care coverage under any public or private health insurance plan.

Data were analyzed by using SPSS for Windows, version 11.0. Bivariate relationships were examined by using odds ratios. Logistic regression equations were used to examine multivariate models and to obtain adjusted odds ratios. Confidence intervals (CIs) of 95 percent were calculated for all odds ratios. Although the sample closely approximated the population of women in California, the data were weighted in the analyses to reflect the age and ethnicity distributions of California women according to the year 2000 census.

Results

A total of 14.8 percent of this sample of women in California perceived need, sought services, and ultimately used specialty mental health services in the previous year. A total of 29.2 percent of the women reported perceived need for services, and 17 percent of the women sought specialty mental health services. Frequent mental distress was reported by 14.2 percent of the women (13.7 percent of Caucasian women, 14.6 percent of African-American women, 16.4 percent of Hispanic women, 11 percent of Asian-American women, and 20.4 percent in the Native American or other category). Frequent mental distress was associated with significantly increased odds of reporting perceived need for mental health services (OR=4.5, CI=3.7 to 5.3, p<.01) but not service seeking (OR=.9, CI=.7 to 1.2, p=.39) or utilization (OR=.7, CI=.4 to 1.1, p=.14).

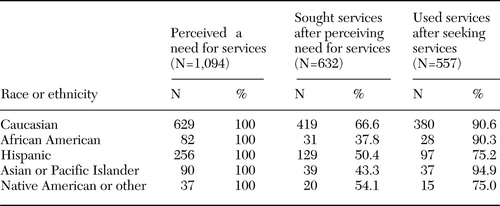

Unadjusted proportions of women who responded affirmatively to the items about perceived need for mental health services, service seeking, and use of mental health services are described in Table 1. Because administration of these items was nested, we present conditional proportions of service seeking and utilization within each racial and ethnic category—that is, service seeking is presented as a proportion of women with perceived need, and utilization is presented as a proportion of women who sought services. The data in the table suggest that the proportion of women who reported perceived need and who sought mental health services (57.8 percent) was somewhat lower than the proportion of women who sought services and then used services (88.1 percent).

Among Caucasian women, 66.6 percent of those who perceived a need for mental health services in the previous year sought those services. Among other women, the proportion was markedly lower: only 37.8 percent of African-American women with perceived need sought services; the corresponding percentages for Hispanic and Asian women were 50.4 percent and 43.3 percent, respectively. However, most women who sought services obtained them: 90.6 percent of Caucasian women, 90.3 percent of African-American women, and 94.9 percent of Asian women. Hispanic women appear to be a notable exception—only 75.2 percent of women who sought services obtained services in the previous year.

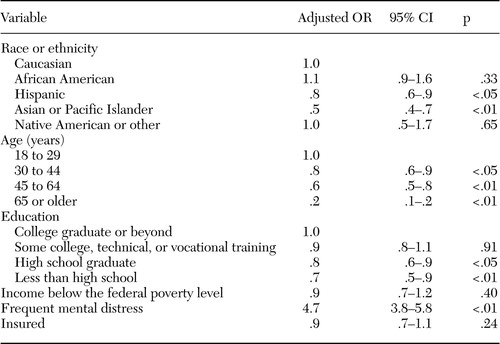

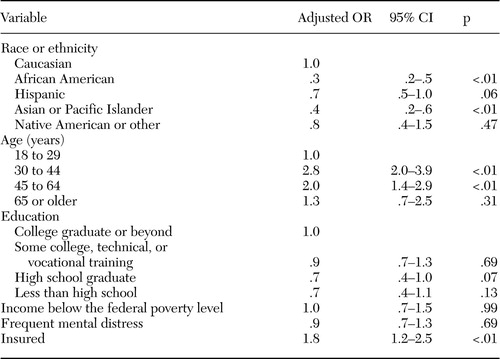

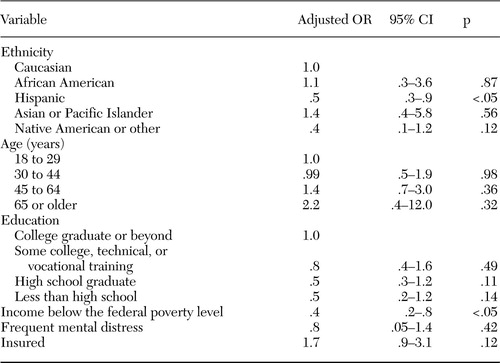

Racial and ethnic variation in access to specialty mental health services was further examined to assess specific factors associated with each stage of access to care in the Anderson model. Multivariate models were constructed to determine whether disparities persisted after predisposing and need factors had been taken into account. Each model included race or ethnicity, age, education, presence of frequent mental distress, income below the federal poverty level, and health insurance status. The factors associated with perceived need are shown in Table 2. In the subset of women who reported perceived need, we then investigated factors uniquely associated with service seeking, as shown in Table 3. Finally, in the subset of women who reported seeking services, we investigated factors uniquely associated with service use, as shown in Table 4.

Perceived need

Racial and ethnic variation in perceived need for mental health services was observed after adjustment for need and predisposing factors: both Hispanic and Asian women were significantly less likely than white women to perceive a need for specialty mental health services. The strongest predictor of perceived need for mental health services was frequent mental distress. Women who reported frequent mental distress were more than four times as likely as other women to report a need for mental health services in the previous year. Older women and women with lower educational attainment were significantly less likely to report perceived need for specialty mental health services.

Service seeking

Racial and ethnic variation was also observed in service seeking: African-American women and Asian women were significantly less likely than white women to seek specialty mental health services when they believed they needed services. Women aged 30 to 64 years and women with health insurance were significantly more likely to seek services in the context of perceived need.

Service use

Among women who sought mental health services, Hispanic women were significantly less likely than white women to obtain these services. The only other factor associated with barriers to obtaining specialty mental health services among women who sought services was income below the federal poverty level.

Discussion

Approximately half of this sample of women in California who perceived a need for specialty mental health services, or an estimated 1.5 million women, had not obtained such services in the previous year. The results of our study suggest that women who are not white are significantly overrepresented among underserved women. These results suggest significant racial and ethnic disparities in the use of mental health services that appear to be a function of both women's willingness to seek services and barriers to care among service-seeking women. Racial and ethnic variation was observed in women's perceived need for mental health services, service-seeking behavior, and service use.

In multivariate models, need, enabling factors, and demographic variables did not completely account for the observed racial and ethnic differences. Most notably, no factors in our model accounted for the significant gap between women's perceived need for services and service-seeking behavior. These results suggest that barriers to specialty mental health services exist at each stage of this model and that these barriers are specifically associated with race or ethnicity.

Our results emphasize the important role of accounting for an individual's perceived need for services. Although perceived need had a strong association with frequent mental distress, racial and ethnic differences were apparent. Multivariate analyses indicated that even after mental distress was accounted for, both Hispanic and Asian-American women reported lower levels of perceived need than did white women. Asian-American and Hispanic women may be less likely to conceptualize specialty mental health services to be an efficacious or culturally consistent response to mental distress.

Because we found that enabling and need factors did not account for observed racial and ethnic variations in perceived need, studies with larger samples should now investigate whether these enabling and need factors predict perceived need for services differently within specific racial and ethnic groups. An important question at this level of access to care is whether racial and ethnic differences in perceived need are a result of cultural variations in patients' preferences for mental health services and whether outreach or other types of intervention may help to ameliorate associated racial and ethnic inequalities in access to specialty mental health services.

We observed a significant gap between women who reported perceived need for services and those who sought these services: only 57.8 percent of women who reported perceived need sought mental health services. However, among women who sought services, 88.1 percent had used services in the previous year. Rates of service seeking were significantly lower among African-American and Asian women, even after other factors in the model had been taken into account. Thus, although some racial and ethnic inequalities clearly stem from barriers to access to services encountered by women seeking specialty mental health care, a substantial portion of inequalities in use of specialty mental health services appears to stem from factors that prevent women from seeking the care they believe they need.

It is important to note that our study examined specialty mental health care only and did not assess mental health treatments that are often provided in primary care settings, such as pharmacologic treatments. A potential explanation for our results is that individuals who receive mental health care in the general medical sector, but not adjunct specialty care, are more likely to be nonwhite and female (20). Thus patients do not seek specialty mental health care and instead obtain services in primary care settings. More research is needed to assess the quality of mental health care for African-American, Asian, and Hispanic women in primary care. The depression literature suggests that patients from ethnic minority groups are less likely to receive treatment through primary care and are less likely than white patients to find either counseling or pharmacotherapy acceptable treatments (21).

Women who are not white may also be less likely to seek the specialty care they believe they need because of previous experiences with the health care system, referral patterns in the general medical sector and institutional structure, or access to other social or material resources that influence whether a woman seeks the services she believes she needs. Our findings indicate that having health insurance significantly increased the likelihood that a woman would seek mental health services, although even after insurance and other factors had been taken into account, African-American women and Asian women were less likely to seek the mental health services they believed they needed. As some research suggests, previous experiences may influence the likelihood of seeking mental health services at any given time (9).

The quality of the patient-provider relationship appears to be associated with women's willingness to seek mental health services (22). Research also suggests that physicians are less likely to detect mental health problems among African-American and Hispanic patients (23). If the mental health problems of nonwhite women are less likely to be detected and if such patients are less frequently referred to mental health services, they also may be subsequently less likely to seek such services, despite perceived need. Further investigation of both patients' preferences and provider and institutional behavior is needed and may promote understanding of why women from racial and ethnic minority groups may be disproportionately less likely to seek the services they believe they need. Such research must also address workforce issues, cultural competence, and other factors that define a service system's capacity to effectively treat women of diverse language, culture, and ethnicity.

It is notable that even among women who perceived a need for specialty mental health services and sought those services, racial and ethnic differences in use persisted even after other variables, including insurance status, had been taken into account. This finding indicates that Hispanic women were significantly less likely to use specialty mental health services than were white women, even after adjustment for need and enabling and demographic variables, including the important role of poverty. Because this finding is specific to women who perceived a need for services and sought those services, our results suggest that Hispanic women may face specific barriers to the use of specialty mental health services, and research is needed that addresses these particular disparities in access to care.

The results of this study point to several avenues of research that could help to illuminate racial and ethnic disparities in access to specialty mental health services. However, these results should be interpreted with some caution. The findings are preliminary, rather than definitive, and need to be replicated in studies that include more precise indicators of mental health status and service use and that allow a greater exploration of variation within racial and ethnic groups. Our results refer to specialty mental health services only and do not address mental health care delivered in nonspecialty settings, such as primary care. Furthermore, we did not include measures of type of mental health treatment or treatment intensity. These results cannot be generalized to men without further study.

The strengths of the study lie in the expanded exploration of access to care and the use of a diverse representative sample of women. We documented racial and ethnic variation in perceived need for services, service seeking, and service utilization guided by the Anderson behavioral model. Our results suggest that racial and ethnic disparities in access to specialty mental health care exist and that there is a need for significant intervention to meet the mental health service needs of nonwhite women.

Conclusions

After predisposing and need factors were taken into account, significant racial and ethnic variation in access to specialty mental health services was observed in this sample of California women. Hispanic and Asian women were less likely to report perceived need, even after adjustment for mental distress. Among women with perceived need, African-American and Asian women were less likely to seek services, even after adjustment for insurance status. Among women who sought services, Hispanic women were less likely to obtain services, even after adjustment for poverty. Need and enabling factors did not entirely account for observed racial and ethnic disparities in access to specialty mental health services, and additional research is needed that can identify gender and culture-specific models for access to mental health services in order to decrease disparities in access. Factors such as perceived need and decisions to seek services are important variables that should be emphasized in future studies.

Dr. Kimerling is affiliated with the National Center for PTSD, Palo Alto Department of Veterans Affairs Healthcare System, 795 Willow Road, PTSD-334, Menlo Park, California 94025 (e-mail, [email protected].) Dr. Baumrind is with the research and evaluation branch of the California Department of Social Services in Sacramento.

|

Table 1. Need for and use of mental health services by race or ethnicity in a sample of 3,750 women in California

|

Table 2. Multivariate model of perceived need for mental health services in a sample of 3,750 women in California

|

Table 3. Multivariate model of service seeking in a sample of 1,094 women in California with a perceived need for services

|

Table 4. Multivariate model of use of mental health services in a sample of 632 California women who sought services

1. National Healthcare Disparities Report. Rockville, Md, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2004Google Scholar

2. Wells K, Klap R, Koike A, et al: Ethnic disparities in unmet need for alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health care. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:2027–2032,2001Link, Google Scholar

3. Alegria M, Canino G, Rios R, et al: Inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among Latinos, African Americans, and non-Latino whites. Psychiatric Services 53:1547–1555,2002Link, Google Scholar

4. Chow JC, Jaffee K, Snowden L: Racial/ethnic disparities in the use of mental health services in poverty areas. American Journal of Public Health 93:792–797,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. McAlpine DD, Mechanic D: Utilization of specialty mental health care among persons with severe mental illness: the roles of demographics, need, insurance, and risk. Health Services Research 35:277–292,2000Medline, Google Scholar

6. Anderson RM: Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36:1–10,1995Google Scholar

7. Lin KM, Cheung F: Mental health issues for Asian Americans. Psychiatric Services 50:774–780,1999Link, Google Scholar

8. Diala CC, Muntaner C, Walrath C, et al: Racial/ethnic differences in attitudes toward seeking professional mental health services. American Journal of Public Health 91:805–807,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Diala C, Muntaner C, Walrath C, et al: Racial differences in attitudes toward professional mental health care and in the use of services. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 70:455–464,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Freiman MP, Zuvekas SH: Determinants of ambulatory treatment mode for mental illness. Health Economics 9:423–434,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Albizu-Garcia CE, Alegria M, Freeman D, et al: Gender and health services use for a mental health problem. Social Science and Medicine 53:865–878,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Sherbourne CD, Wells KB, Duan N, et al: Long-term effectiveness of disseminating quality improvement for depression in primary care. Archives of General Psychiatry 58:696–703,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. California Women's Health Survey: SAS Dataset Documentation and Technical Report, 2001. Sacramento, Calif, California Department of Health Services, 2002Google Scholar

14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Self-reported frequent mental distress among adults: United States, 1993–1996. JAMA 279:1772–1773,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Andresen EM, Fitch CA, McLendon PM, et al: Reliability and validity of disability questions for US Census 2000. American Journal of Public Health 90:1297–1299,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Moriarty DG, Zack MM, Kobau R: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's healthy days measures: population tracking of perceived physical and mental health over time. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 1:37,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Brown DW, Balluz LS, Ford ES, et al: Associations between short- and long-term unemployment and frequent mental distress among a national sample of men and women. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 45:1159–1166,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Strine TW, Balluz L, Chapman DP, et al: Risk behaviors and healthcare coverage among adults by frequent mental distress status, 2001. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 26:213–216,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Poverty in the United States:2000. Washington, DC, US Census Bureau,2002Google Scholar

20. Cooper-Patrick L, Crum RM, Ford DE: Characteristics of patients with major depression who received care in general medical and specialty mental health settings. Medical Care 32(1):15–24,1994Google Scholar

21. Miranda J, Cooper LA: Disparities in care for depression among primary care patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine 19:120–126,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Scholle SH, Kelleher K: Preferences for depression advice among low-income women. Maternal Child Health Journal 7:95–102,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Borowsky SJ, Rubenstein LV, Meredith LS, et al: Who is at risk of nondetection of mental health problems in primary care? Journal of General Internal Medicine 15:381–388,2000Google Scholar