Rehab Rounds: Improving Social Functioning in Schizophrenia by Playing the Train Game

Abstract

Introduction by the column editors: Social impairments have long been recognized as a core feature of schizophrenia. Poor social, self-care, and vocational functioning are criteria for a diagnosis of schizophrenia in most diagnostic systems. Consequently, improving the social behaviors of persons with schizophrenia has been a key target of psychiatric rehabilitation techniques.One such technique, social skills training, has demonstrated effectiveness in yielding skill acquisition, durability, and generalization (1) and has been recognized as a psychosocial treatment of choice for schizophrenia (2). Nevertheless, a number of limitations to the benefits that may be achieved through skills training have been described. For example, the cognitive impairments of persons with schizophrenia, such as poor sustained attention and verbal memory deficits, have been shown to limit the acquisition of social skills (3). Moreover, one study showed that patients with negative symptoms, such as apathy, anhedonia, and amotivation, have an impaired capacity to benefit from social skills training (4). However, the results of a more recent study suggest that only persons with primary, deficit-type negative symptoms—not those with negative symptoms secondary to positive psychotic symptoms, depression, or extrapyramidal side effects—are unable to benefit from conventional social skills training (5).Recognizing these obstacles to implementing a social skills training program for persons with schizophrenia, Torres and his colleagues have created a board game called El Tren (The Train). Several characteristics of El Tren make it ideal for use with this population. First, the game is behaviorally oriented and has an emphasis on positive reinforcement and shaping. Second, it is sensitive to the cognitive limitations of the participants, emphasizing repetition and procedural learning. Third, it is designed to overcome participants' negative symptoms by being entertaining and fun. In this month's column, these authors describe El Tren and present the results of a randomized controlled study of its efficacy.

The game El Tren, or The Train, simulates a railway trip in which unexpected problems are encountered and solved as the train passes through each station. Clients participate in four teams of two to four players while therapists serve as train conductors to facilitate travel to a final destination. Along the way, clients develop problem-solving skills, communication skills, and illness-self-management skills and learn how to distinguish between positive and negative situations. Moreover, the game uses cognitive remediation techniques designed to overcome clients' learning deficits.

El Tren is a board game that uses dice, game cards, and test cards. Players on each team take turns rolling the dice and moving their pieces around the board. Spaces on the board direct the player to select a game card, which identifies the train station to which he or she must proceed. At the train station, the player picks up a test card that presents the problem the team must try to solve. Examples of problems are "Vagrancy and begging are symptoms of serious social and personal deterioration. What are other signs of deterioration?" and "Recite the months of the year backwards." When the problem is successfully solved, a star is awarded. The team with the most stars at the end of the journey wins the game, which generally lasts from 60 to 90 minutes. An instructional manual with a more detailed description of El Tren is available from the first author.

Methods

A test of the efficacy of El Tren was conducted at the Xeral-Cies Hospital in Vigo, Spain. The study was approved by the hospital's institutional review board. After the participants were given a complete description of the study, written informed consent was obtained. The participants were 49 Spanish-speaking clients, 36 men and 13 women, who were actively participating in the hospital's day rehabilitation center. At the time of the study, all participants met DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia and were receiving antipsychotic medication. The clients' ages ranged from 18 to 50 years; 80 percent of them were between the ages of 25 and 40 years. The mean duration of psychotic illness was eight years. Most of the participants were single, lived in an urban environment with their immediate families, and were unemployed.

The participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups. Group 1 (N=19) participated in a program that included El Tren, social skills training, psychomotor skills training, and occupational therapy. Group 2 (N=16) participated in social skills training, psychomotor skills training, and occupational therapy but did not play El Tren. Group 3 (N=14) received occupational therapy only. The participants in group 1 played El Tren for one hour a week. The participants in groups 1 and 2 received social skills training and psychomotor skills training for three hours a week. The participants in all three groups were involved in occupational therapy for five hours a week. The intervention was conducted over a period of six months (January through July 2000).

The psychomotor skills training included several physical exercises that facilitate the development of equilibrium, rhythm, and coordination. These exercise sessions, which were led by trained recreational therapists, were designed to encourage clients to incorporate physical activity into their daily lives by making these aerobic routines energizing, health promoting, and fun. The social skills training focused on enhancing clients' ability to use verbal and nonverbal methods to improve their interpersonal relationships and quality of life. The sessions aimed to teach clients how to receive, process, and send social communication signals (6). The occupational therapy consisted of a variety of activities designed to improve fine and gross motor movements and used primarily arts and crafts techniques.

The principal outcome measure was the Social Functioning Scale (7). This scale is composed of seven subscales—social withdrawal, interpersonal functioning, independence (competence), independence (performance), recreational activities, prosocial activities, and work. The instrument was completed on the basis of information provided by the study participant and a key relative and was administered at baseline and after six months.

Results

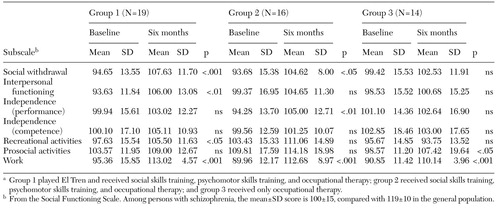

At baseline, no significant differences in demographic characteristics, clinical history, or social functioning were observed between the three groups. The mean social functioning scores of the three groups at baseline and after six months are listed in Table 1. Within-group comparisons using paired-sample t tests showed that the participants in group 1 achieved significant improvement in four of the seven subscales of the Social Functioning Scale over the study period—social withdrawal, interpersonal functioning, recreational activities, and work. The participants in group 2 improved significantly on three subscales—social withdrawal, independence (performance), and work, while those in group 3 displayed significant improvements in prosocial activities and work.

Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) using baseline variables as covariates was conducted to examine between-group differences. This ANCOVA yielded significant F values for all subscales except independence (competence). Independent-sample t tests were used to compare between-group differences at six months, with baseline values controlled for. The participants in group 1 demonstrated significantly greater improvement in interpersonal functioning than the participants in the other two groups (t=5.38 for group 1 versus group 2, df=33, p<.001; t=32.9 for group 1 versus group 3, df=31, p<.001) and significantly greater improvement in social withdrawal than the participants who were assigned to group 3 (t=10.24, df=31, p<.001) but not those who were assigned to group 2.

Conclusions

Given that El Tren has been tested at only one center, this new resource needs to be tested in similar centers around the world to cross-validate the results of this study. El Tren may be used as an additional tool in a package of psychiatric rehabilitation, thus adding a systematically organized, behaviorally oriented, and entertaining treatment modality to the armamentarium of rehabilitation practitioners who are looking to enhance the personal effectiveness of people with schizophrenia.

Afterword by the column editors:

Because of differences in baseline levels of social functioning in this study, analysis of covariance provides the best indicator of the relative value of El Tren as a rehabilitative technique. The authors' finding that the participants who were assigned to the El Tren condition improved in terms of social withdrawal and interpersonal functioning may be explained by generalization from the social activity associated with playing El Tren or by the fact that these individuals continued to play El Tren or similar games outside of the weekly session dictated by the study design. The authors may not have monitored the participants for their continued use of the game outside the designated sessions, but if the game is as enjoyable and engaging as was described, it is likely that they did continue to play it, which could explain the differences. The fact that only the participants who were assigned to the El Tren condition showed significant within-group improvement on the recreational activities subscale of the Social Functioning Scale may support the latter explanation.

Instilling structured, prescriptive steps in a game procedure and providing positive feedback on successful participation in a game that is easy to play are excellent programmatic elements for social rehabilitation. A number of board games have been marketed in the United States for eliciting conversation. Liberman (8) used a modified board game to increase social participation in a group of patients with chronic schizophrenia in a long-stay psychiatric hospital. Clinical investigators in Switzerland and France have developed such board games for the same purpose (9).

Dr. Torres and Dr. Mendez are clinical psychologists at the Complejo Hospitalario Xeral-Cies in Vigo, Spain. Dr. Merino is professor of clinical psychology and psychobiology at the University of Santiago de Compostela in Spain. Dr. Moran is a behavioral science consultant at the San Fernando Mental Health Center in Mission Hills, California. Send correspondence to Dr. Torres at Elduayen 45-2A, 36202 Vigo (Pon Tevedra), Spain (e-mail, [email protected]). Alex Kopelowicz, M.D., and Robert Paul Liberman, M.D., are editors of this column.

|

Table 1. Social functioning at baseline and after six months in three groups of patients with schizophreniaa

a Group 1 played El Tren and received social skills training, psychomotor skills training, and occupational therapy; group 2 received social skills training, psychomotor skills training, and occupational therapy; and group 3 received only occupational therapy.

1. Heinssen RK, Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A: Psychosocial skills training for schizophrenia: lessons from the laboratory. Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:21-46, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM: Translating research into practice: the schizophrenia patient outcomes research team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:1-10, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Green MF: What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? American Journal of Psychiatry 153:321-330, 1996Google Scholar

4. Matousek N, Edwards J, Jackson H, et al: Social skills training and negative symptoms. Behavior Modification 16:39-63, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Kopelowicz A, Liberman RP, Mintz J, et al: Efficacy of social skills training for deficit versus nondeficit negative symptoms in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:424-425, 1997Link, Google Scholar

6. Wallace CJ: Community and interpersonal functioning in the course of schizophrenic disorders. Schizophrenia Bulletin 10:233-257, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Birchwood M, Smith J, Cochrane R, et al: The Social Functioning Scale: the development and validation of a new scale of social adjustment for use in family intervention programmes with schizophrenic patients. British Journal of Psychiatry 157:853-859, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Liberman RP: Reinforcement of social interaction in a group of chronic schizophrenics, in Advances in Behavior Therapy, vol 3. Edited by Rubin R, Franks C, Fensterheim H, et al. New York, Academic Press, 1972Google Scholar

9. Favrod J, Aillon N, Bardoit G: "Competence" un chevel de Troy dans les soins. [A Trojan horse in health care.] Cahiers Psychiatriques Genevois 18:47-53, 1995Google Scholar