Depression and Ischemic Heart Disease Mortality: Evidence From the EPIC-Norfolk United Kingdom Prospective Cohort Study

Abstract

Objective: The authors investigated the association between major depressive disorder, including its clinical course, and mortality from ischemic heart disease. Method: This was a prospective cohort study of 8,261 men and 11,388 women 41–80 years of age who were free of clinical manifestations of heart disease and participated in the Norfolk, U.K., cohort of the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer. The authors conducted a cross-sectional assessment of major depressive disorder during the period 1996–2000 and ascertained subsequent deaths from ischemic heart disease through linkage with data from the U.K. Office for National Statistics. Results: As of July 31, 2006, 274 deaths from ischemic heart disease were recorded over a total follow-up of 162,974 person-years (the median follow-up period was 8.5 years). Participants who had major depression during the year preceding baseline assessment were 2.7 times more likely to die from ischemic heart disease over the follow-up period than those who did not, independently of age, sex, smoking, systolic blood pressure, cholesterol, physical activity, body mass index, diabetes, social class, heavy alcohol use, and antidepressant medication use. This association remained after exclusion of the first 6 years of follow-up data. Consideration of measures of major depression history (including recency of onset, recurrence, chronicity, and age at first onset) revealed recency of onset to be associated most strongly with ischemic heart disease mortality. Conclusions: Major depression was associated with an increased risk of ischemic heart disease mortality. The association was independent of established risk factors for ischemic heart disease and remained undiminished several years after the original assessment.

A recent projection of future population health (1) concluded that by 2030, unipolar depressive disorders and ischemic heart disease (IHD) will be among the three leading causes (with HIV/AIDS) of disease burden worldwide. This vision of the future varied little with whether projections were based on baseline, pessimistic, or optimistic scenarios, and it is consistent with earlier evidence-based projections of global disease (2) .

Heart disease and depression are commonly comorbid (3) , are considered to have a bidirectional relationship (4) , and are associated with substantial and broadly equivalent physical functional impairment (5) . Evidence from prospective healthy cohort studies has reinforced earlier conclusions that depression is associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality (6 – 8) and incident cardiovascular disease (9 , 10) . However, interpretation of this evidence is subject to considerable uncertainty given the syndromal and diagnostic complexity and the wide variability in severity, comorbidity, and clinical history of depressive disorders. Meta-analyses have so far been unable to provide insight into whether and how this clinical heterogeneity differentiates subsequent heart disease risk (8 , 10 – 13) . For example, after conducting a systematic literature search of reports of the association between depression and heart disease, the authors of a recent meta-analysis (13) found that only 28 studies (of 1,610 provisionally identified) met methodological quality inclusion criteria, and of these, only four were reported to have included a baseline assessment of major depressive disorder defined by diagnostic criteria. Even then, this subgroup of studies was limited by sample size, endpoint rarity, and lack of capacity to adjust for established cardiovascular risk factors. Consequently, fundamental questions remain about the origin of IHD risk associated with depressive phenomenology (14) .

Using data collected from participants free of established heart disease in the Norfolk, U.K., cohort of the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer (EPIC-Norfolk) (15) , a population-based prospective cohort study, we investigated the associations between major depression and IHD mortality, independent of established risk factors, including cigarette smoking, physical exercise, alcohol use, and obesity, over an 8-year follow-up period. More specific aims were to establish whether these associations were consistent by sex and varied according to depression history (defined by age at first onset and by measures of onset recency, recurrence, and chronicity). Given recent evidence suggesting that depressive symptom dimensions differentiate outcomes after myocardial infarction (16) , we also investigated whether specific depressive symptoms varied in their associated future risk of IHD mortality.

Method

Residents of the county of Norfolk were recruited into the EPIC-Norfolk study from 1993 to 1997 by use of general-practice age-sex registers (15) . At baseline, details of previous physician-confirmed medical conditions, including angina, myocardial infarction, and diabetes, were noted, along with current and lifetime cigarette smoking behavior and social class defined according to the Registrar General’s occupation-based classification scheme. A subsequent health check attendance included assessment of systolic blood pressure (in mm Hg), based on the mean of two readings taken by trained nurses. Body mass index (BMI) was determined (kg/m 2 ), and serum total cholesterol was estimated from nonfasting blood samples. A validated physical activity index was derived from two questions on past-year work and recreational activities and coded as physically inactive, moderately inactive, moderately active, and active (17) . Alcohol consumption (in units per week, where 1 unit=8 g of alcohol) was derived from a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire (18) . Heavy alcohol use was defined as consumption of more than 21 units a week for men and more than 14 units a week for women. Antidepressant medication use during a 1-week preassessment period was obtained through self-report questionnaire approximately 6 months before the assessment of major depression status was made. Antidepressant medication use was defined according to the British National Formulary (Section 4.3) and included tricyclic (or related) antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (and related antidepressants), and other antidepressants.

Assessment of Episodic Major Depressive Disorder

From 1996 to 2000, an assessment of social and psychological circumstances based on the Health and Life Experiences Questionnaire (5) was completed by a total of 20,921 participants, representing a response rate of 73.2% of the total eligible EPIC-Norfolk sample (28,582). The questionnaire included a structured self-assessment approach to psychiatric symptoms embodying restricted DSM-IV (19) criteria for episodic major depression. The assessment was designed to identify participants who were likely to have met diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder at any time in their lives and to provide evidence of illness chronicity. Given that it was beyond the scope of the Health and Life Experiences Questionnaire to check fully for DSM-IV specified exclusions, only symptoms and clinically significant distress or impairment were assessed for major depression episodes. The assessment procedure depends on participants initially disclosing details of their most recent episode of depression that lasted for at least 2 weeks and that fulfilled the required concurrent DSM-IV symptom criteria for major depressive disorder. Additionally, operational criteria for clinically significant impairment and help seeking were included in the self-assessment, and participants were asked to estimate the timing of episode onset and (if appropriate) offset and to provide an outline of previous history that included age at first onset, the total number of episodes experienced, and the average duration of these episodes. We defined 12-month major depression as any episode that either was current at the time of assessment with the Health and Life Experiences Questionnaire or ended within the 12 months preceding the assessment (see reference 20 for further details, including the questionnaire’s major depressive disorder assessment module).

Assessment of Ischemic Heart Disease Mortality

Participants with a history of either myocardial infarction or angina at baseline were excluded, leaving for analysis a sample of 19,649 participants (of 20,921) assessed by the Health and Life Experiences Questionnaire. The vital status of all EPIC-Norfolk participants was ascertained up to July 31, 2006, through linkage with the U.K. Office for National Statistics. Death certificates for all decedents were coded by trained nosologists according to ICD-9 or ICD-10 specifications. Death was counted as being due to IHD if the underlying cause was coded as ICD-9 410–414 or ICD-10 I20–I25.

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were conducted in Stata, version 8.2 (21) . Prevalence rates of 12-month major depression were computed, both with and without adjustment for age and sex, according to established IHD risk factors and antidepressant medication use, with differences assessed through likelihood ratio tests derived from logistic regression models. The associations between 12-month major depression and IHD mortality were assessed using Cox proportional hazards regression. Results are presented as hazard ratios for men and women separately as well as combined and adjusted for age (in 5-year bands) and sex and subsequently for cigarette smoking, systolic blood pressure, total serum cholesterol level, physical activity, BMI, preexisting diabetes, social class, heavy alcohol use, and antidepressant medication use. Cigarette smoking (coded as current, former, or never), physical activity (inactive, moderately inactive, moderately active, or active), and social class (I [professionals], II [managerial and technical occupations], III [nonmanual skilled workers], III [manual skilled workers], IV [partly skilled workers], or V [unskilled manual workers]) were included as categorical variables. Systolic blood pressure, cholesterol level, and BMI were included as continuous variables. Sex differences were tested through inclusion of interaction terms.

The association between major depression and IHD mortality was evaluated for men and women combined and with adjustment for age and sex, according to length of follow-up (with differences assessed through the proportional hazards test), and with stratification for age, cigarette smoking, physical activity, and antidepressant medication use; differences according to these variables were tested through the inclusion of interaction terms. In addition, the association between major depression and IHD mortality was investigated according to recency of major depression, the total number of episodes experienced, episode duration, and age at onset of first episode. Finally, hazard ratios for IHD mortality, adjusted for age and sex, were computed according to somatic and cognitive symptoms of depression for which the participant satisfied the diagnostic “entry” criteria (either feelings of sadness or depression or loss of interest, for a period of 2 weeks or more), reported the symptom, and was experiencing the symptom at the time of, or within the 12 months preceding, completion of the Health and Life Experiences Questionnaire.

The study was approved by the Norwich District Health Authority Ethics Committee. Participants provided written informed consent after receiving a complete description of the study.

Results

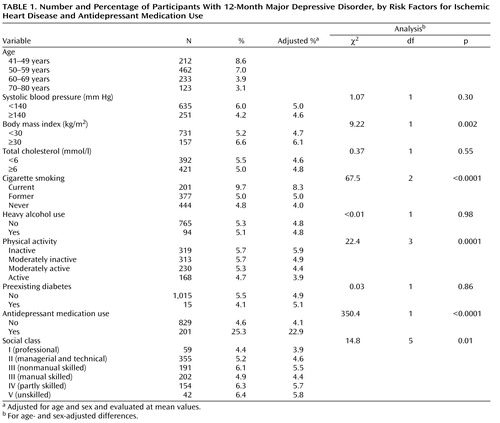

Of 19,649 study participants (8,261 men and 11,388 women), 3,057 (15.6%) reported at least one episode of major depression at some time in their lives (936 men [11.3%] and 2,121 women [18.6%]). Of these episodes, 1,030 (5.2%) were experienced within the previous 12 months (308 [3.7%] for men and 722 [6.3%] for women), and 586 (3.0%) were current at the time the questionnaire was completed (197 [2.4%] in men and 389 [3.4%] in women). Table 1 lists prevalence rates of 12-month major depression according to IHD risk factors and antidepressant medication use. The 12-month prevalence rates of major depression were higher for younger than for older participants (χ 2 =150.1, df=3, p<0.0001). After adjustment for age and sex, rates of 12-month major depression were higher for participants who were obese, were current cigarette smokers, were less physically active, reported antidepressant medication use, and were of lower social class.

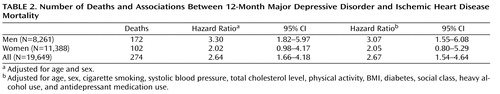

During a total follow-up of 162,974 person-years (the median follow-up period was 8.5 years), there were 274 deaths from IHD. Table 2 shows that 12-month major depression was associated with an increased risk of IHD mortality (χ 2 =13.2, df=1, p=0.0003, after adjustment for age and sex). After additional adjustment for cigarette smoking, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol level, physical activity, BMI, diabetes, social class, heavy alcohol use, and antidepressant medication use, the association of major depression and IHD mortality was of similar magnitude and remained significant (χ 2 =9.64, df=1, p=0.002), such that participants who reported an episode of major depression within 12 months of assessment were 2.7 times more likely to die from IHD over the 8.5-year follow-up period. The magnitude of this association was greater for men than for women, although this difference was not significant (p=0.20 for test of interaction, after adjusting for age).

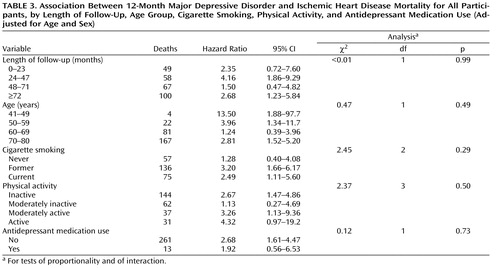

Table 3 shows the association between 12-month major depression and IHD mortality for men and women combined (adjusted for age and sex) and stratified according to length of follow-up, IHD risk factors, and antidepressant medication use. The table reveals no evidence of attenuation in this association with increasing length of follow-up (p=0.99 for test of proportional hazards), and the association remained after exclusion of the first 6 years of follow-up data. The magnitude of association was larger for participants who were younger and those who were current or former smokers, although no significant differences were observed across these variables or according to physical activity or antidepressant medication use.

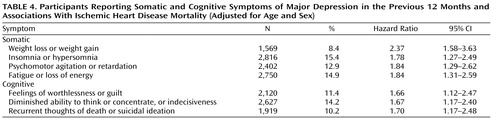

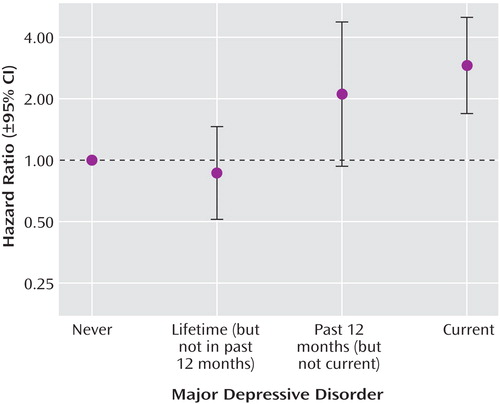

Further analysis investigated the association between 12-month major depression and IHD mortality according to recency of major depression, number of episodes experienced, average duration of episodes, and age at onset of first episode. Figure 1 shows a trend in association according to recency of major depression, such that no association was observed for episodes that were experienced more than 12 months before assessment with the Health and Life Experiences Questionnaire, and the strongest association was observed for episodes of major depression that were current at the time of assessment. In addition, compared with participants who reported no major depression, a stronger association was observed for those who reported three or more episodes (hazard ratio=1.98, 95% CI=1.28–3.05) than for those who reported one or two episodes (hazard ratio=0.94, 95% CI=0.54–1.61, p=0.03 for a test of the difference between these two hazard ratios). Similarly, the association was stronger for participants who reported episodes of major depression that lasted on average 6 months or more (hazard ratio=1.73, 95% CI=1.04–2.88) than for those whose episodes lasted on average less than 6 months (hazard ratio=1.18, 95% CI=0.74–1.89) but was stronger for those whose first episode was at age 40 or older (hazard ratio=1.44, 95% CI=0.93–2.21) than for those whose first episode was before age 40 (hazard ratio=1.04, 95% CI=0.57–1.91), although these differences were not significant. However, when measures of recency of major depression (current versus not current major depression), frequency (three or more versus fewer than three episodes), duration (6 months or more versus less than 6 months or no episodes), and age at first onset (age 40 or older versus under 40 or no episodes) were allowed to compete in the same model, which was also adjusted for age and sex, only recency of major depression was significantly associated with IHD mortality. Finally, Table 4 shows that the association with IHD mortality was observed consistently according to specific symptoms of major depression and that there were no notable differences in association between somatic and cognitive symptoms.

Discussion

We found that study participants who reported episodes of major depression within the 12 months prior to baseline assessment were 2.7 times more likely to have died from IHD over the 8.5-year follow-up. The magnitude of association was greater for men than for women, although sex differences were not statistically significant. There were no notable differences in association between somatic and cognitive symptoms. The association between 12-month major depression and IHD mortality did not attenuate with increasing length of follow-up, it remained after exclusion of the first 6 years of follow-up, and it was independent of age, sex, cigarette smoking, systolic blood pressure, cholesterol level, physical activity, BMI, diabetes, social class, heavy alcohol use, and antidepressant medication use. The association between major depression and IHD mortality was stronger for participants who reported three or more episodes of major depression, for those who reported episodes that lasted on average 6 months or more, and for those whose first episode was at age 40 or older. However, the association was strongest in participants whose depressive episodes were reported as being current at the time of assessment, and no association was observed among those who reported lifetime episodes of major depression that had ended at least 12 months before assessment. In addition, when measures of recency, recurrence, chronicity, and age at first onset were considered together, only recent major depression was significantly associated with IHD mortality. We are unaware of any other study that has been able to evaluate variability in the presentation of major depression and subsequent heart disease mortality. However, researchers from the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam (22) , with a population-based sample of 2,403 older men and women, recently reported that the risk of IHD was three times higher in those with major depression over a 7-year follow-up period than in those without.

Interpretation

In a recent meta-analysis of etiological studies, Nicholson and colleagues (12) found evidence of publication bias, with smaller negative studies missing; lack of adjustment for coronary risk factors in almost half the studies; and evidence of reverse causality, whereby the association between depression and heart disease incidence was strongest during the initial periods of follow-up. They interpreted their findings collectively as casting doubt on the association between depression and heart disease outcome. In our study we found an association only for 12-month (and not for lifetime) major depression. We also found that the recency of major depression was more strongly related to IHD mortality risk than were measures of depression chronicity over the life course. One explanation of these findings is that the observed relationship between major depression and subsequent development of IHD may not be causal, and that both depression and subsequent coronary events are a consequence of undiagnosed subclinical manifestations of cardiovascular disease (9) . Retrospective collection of lifetime history of major depression has only moderate reliability in epidemiological studies (23) . An alternative explanation therefore is that recall and measurement errors are more pronounced for lifetime than for more recent episodes of depression. In addition—and a further argument against the explanation that both major depression and future coronary outcomes are undiagnosed subclinical manifestations of the same underlying process—we observed cognitive as well as somatic symptoms of depression to be associated with future IHD mortality.

The question remains as to why individuals with a history of depression have an increased risk of heart disease. Evidence suggests that depression may contribute to the risk of IHD through promoting atherogenesis, plaque rupture, pathophysiological mechanisms involving platelet abnormalities, reduced heart rate variability, involvement of inflammatory innate immune responses, and raised levels of homocysteine concentrations, collectively providing biological plausibility for depressive states as important determinants of heart health (24 – 30) . Yet no association was found between depression and coronary calcium (a marker of subclinical atherosclerosis, and predictive of incident cardiovascular disease endpoints in asymptomatic individuals) in a large multiethnic community-based population (31) .

A further potential explanation for the more proximal relationship of major depression with IHD mortality found in this study is that major depression may not be a risk factor for the progression of atherosclerosis, given that such progression may take decades to develop. Instead, depression may be involved in the process that leads to cardiovascular events, especially those related to mortality, among patients who already have significant atherosclerosis. One of the candidate mechanisms that may underlie this heightened risk is autonomic nervous system dysfunction. For example, autonomic dysfunction has been observed in patients with depression following cardiovascular events, and this may increase their risk of lethal arrhythmias. Consistent with this idea is the finding that depression is a better predictor of fatal recurrent myocardial infarction or sudden cardiac death than of nonfatal recurrent infarction in patients with a recent acute myocardial infarction (32 – 34) .

In this study, the association between 12-month major depression and IHD mortality was shown to be independent of a wide range of IHD risk factors often unavailable for adjustment in other studies (12 , 14) . In addition, 12-month major depression was not associated with preexisting diabetes, systolic blood pressure, or total cholesterol level. These findings suggest that the putative cardiotoxic process marked by depression may not act through traditional IHD risk factor pathways. The association of depression with heart disease outcomes may therefore depend substantially on pathways defined by behavioral and lifestyle choices, given evidence (including from this study) concerning the association of depression with cigarette smoking, physical inactivity, unhealthy dietary patterns, and medication nonadherence (35 , 36) . Depression may therefore serve to encourage the adoption of cardiotoxic lifestyles that over time accumulate in their effects but that would be better evaluated through sequential assessments over the life course.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this study include the cohort size, prospective ascertainment of mortality endpoints (with 274 IHD deaths in more than 160,000 person-years of follow-up), availability of data for both men and women, baseline assessments that allowed adjustment for a wide range of risk factors often not available in other studies (including cigarette smoking, alcohol use, physical illness, cholesterol level, and antidepressant medication use), and depression defined according to diagnostic criteria. However, a number of important limitations warrant discussion. First, the structured self-assessment approach of the Health and Life Experiences Questionnaire represents a pragmatic means of enabling measures of emotional state, representative of core DSM-IV diagnostic criteria, to be included in a large-scale chronic disease epidemiological study. These measures have allowed discrimination of first onset and recurrence risks of depression (37) , demonstration of physical functional impairment associated with mood disorders relative to that associated with chronic medical conditions (5) , and evaluation of genetic models of association with depression (38 , 39) . Based on a subsample of these data, previous work has shown that prevalence estimates of DSM-IV major depressive disorder and associated demographic risk profiles are broadly similar to those derived from dedicated large-scale psychiatric epidemiology research studies, and that there was little evidence of reported episodes clustering in the period immediately prior to assessment (20) . While international comparison of major depressive disorder defined in terms of diagnostic criteria requires caution (40) , recent work continues to provide evidence of similar prevalence rate estimates (see reference 41 for a review). For example, DSM-IV 12-month and lifetime major depression prevalence rates of 6.6% and 16.2% (ratio of 2.5:1) based on use of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (42) compare to rates of 5.2% and 15.6% (ratio of 3:1) in this community study of somewhat older participants. Second, we are unable to exclude the possibility of residual confounding due to errors in the measurement of important potential confounding variables, such as smoking behavior, or from measures less commonly assessed, such as heavy alcohol use. Third, the restricted age range and other characteristics of the EPIC-Norfolk cohort may reduce the generalizability of our findings. Participation in the EPIC-Norfolk study involved commitment to subsequent follow-up assessments and the collection of detailed biological and dietary data. While these requirements resulted in the recruitment of a sample that included fewer current smokers, the cohort is representative of the general population of England in terms of anthropometric variables, blood pressure, serum lipid levels (15) , and physical and mental functional health (43) , and it includes participants in a broad range of socioeconomic circumstances (44) . Fourth, our reliance on diagnostic codes for IHD on death certificates through national mortality statistics, which may be inaccurate (45) , may have led to misclassification of outcome such that the association with current depression may be due partly to an increased risk of all-cause as opposed to IHD-specific mortality.

Conclusions

Beyond early middle age, the remaining lifetime risk of heart disease is considerable, and significant individual risk factors for IHD left untreated will continue to promote atherosclerotic vascular disease (46) . For example, recent evidence suggests that more than half of men and some 40% of women who are free of cardiovascular disease at age 50 will eventually develop cardiovascular disease (47) . While our results support an association between 12-month major depression and IHD mortality, independent of known risk factors, future work will need to establish the extent to which the association is causal or due to residual confounding or to reverse causality; it will also need to focus greater attention on the relationship between behavioral and physiological mechanisms (48) .

Depression can be profoundly disabling, and it presents considerable challenges for detection and for effective care, especially in combination with the specific needs of the elderly. While recent studies have produced encouraging evidence that tailored collaborative (or algorithm-based) care intervention for depression in later life provides clinical benefit (49) that may be sustained over the long term (50) and is associated with reduced mortality (51) , whether such care would contribute to a reduction in heart disease outcomes in broader settings remains unknown.

1. Mathers CD, Loncar D: Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med 2006; 3:e442; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442Google Scholar

2. Murray CJL, Lopez AD (eds): The Global Burden of Disease: A Comprehensive Assessment of Mortality and Disability From Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors in 1990 and Projected to 2020. Global Burden of Disease and Injury Series, vol 1. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1996Google Scholar

3. Rudisch B, Nemeroff CB: Epidemiology of comorbid coronary artery disease and depression. Biol Psychiatry 2003; 54:227–240Google Scholar

4. Plante GE: Depression and cardiovascular disease: a reciprocal relationship. Metabolism 2005; 54:45–48Google Scholar

5. Surtees PG, Wainwright NWJ, Khaw KT, Day NE: Functional health status, chronic medical conditions, and disorders of mood. Br J Psychiatry 2003; 183:299–303Google Scholar

6. Takeshita J, Masaki K, Ahmed I, Foley DJ, Li YQ, Chen R, Fujii D, Ross GW, Petrovitch H, White L: Are depressive symptoms a risk factor for mortality in elderly Japanese American men? the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1127–1132Google Scholar

7. Wassertheil-Smoller S, Shumaker S, Ockene J, Talavera GA, Greenland P, Cochrane B, Robbins J, Aragaki A, Dunbar-Jacob J: Depression and cardiovascular sequelae in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI). Arch Intern Med 2004; 164:289–298Google Scholar

8. Wulsin LR, Evans JC, Vasan RS, Murabito JM, Kelly-Hayes M, Benjamin EJ: Depressive symptoms, coronary heart disease, and overall mortality in the Framingham Heart Study. Psychosom Med 2005; 67:697–702Google Scholar

9. Rugulies R: Depression as a predictor for coronary heart disease: a review and meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med 2002; 23:51–61Google Scholar

10. Wulsin LR, Singal BM: Do depressive symptoms increase the risk for the onset of coronary disease? a systematic quantitative review. Psychosom Med 2003; 65:201–210Google Scholar

11. Davidson KW, Rieckmann N, Rapp MA: Definitions and distinctions among depressive syndromes and symptoms: implications for a better understanding of the depression-cardiovascular disease association. Psychosom Med 2005; 67:S6–S9Google Scholar

12. Nicholson A, Kuper H, Hemingway H: Depression as an aetiologic and prognostic factor in coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of 6,362 events among 146,538 participants in 54 observational studies. Eur Heart J 2006; 27:2763–2774Google Scholar

13. Van der Kooy K, van Hout H, Marwijk H, Marten H, Stehouwer C, Beekman A: Depression and the risk for cardiovascular diseases: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psych 2007; 22:613–626Google Scholar

14. Wulsin LR: Does depression kill? Arch Intern Med 2000; 160:1731–1732Google Scholar

15. Day N, Oakes S, Luben R, Khaw KT, Bingham S, Welch A, Wareham N: EPIC-Norfolk: study design and characteristics of the cohort. Br J Cancer 1999; 80(suppl 1):95–103Google Scholar

16. de Jonge P, Ormel J, van den Brink RHS, van Melle JP, Spijkerman TA, Kuijper A, van Veldhuisen DJ, van den Berg M, Honig A, Crijns HJGM, Schene AH: Symptom dimensions of depression following myocardial infarction and their relationship with somatic health status and cardiovascular prognosis. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:138–144Google Scholar

17. Khaw KT, Jakes R, Bingham S, Welch A, Luben R, Day N, Wareham N: Work and leisure time physical activity assessed using a simple, pragmatic, validated questionnaire and incident cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in men and women: the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer in Norfolk prospective population study. Int J Epidemiol 2006; 35:1034–1043Google Scholar

18. Welch AA, Luben R, Khaw KT, Bingham SA: The CAFE computer program for nutritional analysis of the EPIC-Norfolk food frequency questionnaire and identification of extreme nutrient values. J Hum Nutr Diet 2005; 18:99–116Google Scholar

19. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

20. Surtees PG, Wainwright NWJ, Brayne C: Psychosocial aetiology of chronic disease: a pragmatic approach to the assessment of lifetime affective morbidity in an EPIC component study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2000; 54:114–122Google Scholar

21. Stata Corp: Stata statistical software, release 8.2. College Station, Tex, 2004Google Scholar

22. Bremmer MA, Hoogendijk WJG, Deeg DJH, Schoevers RA, Schalk BWM, Beekman ATF: Depression in older age is a risk factor for first ischemic cardiac events. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006; 14:523–530Google Scholar

23. Kendler KS, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Heath AC, Eaves LJ: The lifetime history of major depression in women: reliability of diagnosis and heritability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:863–870Google Scholar

24. Jones DJ, Bromberger JT, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Matthews KA: Lifetime history of depression and carotid atherosclerosis in middle-aged women. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:153–160Google Scholar

25. Penninx BW, Kritchevsky SB, Yaffe K, Newman AB, Simonsick EM, Rubin S, Ferrucci L, Harris T, Pahor M: Inflammatory markers and depressed mood in older persons: results from the Health, Aging and Body Composition study. Biol Psychiatry 2003; 54:566–572Google Scholar

26. Tolmunen T, Hintikka J, Voutilainen S, Ruusunen A, Alfthan G, Nyyssonen K, Viinamaki H, Kaplan GA, Salonen JT: Association between depressive symptoms and serum concentrations of homocysteine in men: a population study. Am J Clin Nutr 2004; 80:1574–1578Google Scholar

27. Bruce EC, Musselman DL: Depression, alterations in platelet function, and ischemic heart disease. Psychosom Med 2005; 67:S34–S36Google Scholar

28. Carney RM, Blumenthal JA, Freedland KE, Stein PK, Howells WB, Berkman LF, Watkins LL, Czajkowski SM, Hayano J, Domitrovich PP, Jaffe AS: Low heart rate variability and the effect of depression on post-myocardial infarction mortality. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165:1486–1491Google Scholar

29. Liukkonen T, Silvennnoinen-Kassinen S, Jokelainen J, Räsänen P, Leinonen M, Meyer-Rochow VB, Timonen M: The association between C-reactive protein levels and depression: results from the Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort Study. Biol Psychiatry 2006; 60:825–830Google Scholar

30. Raison CL, Capuron L, Miller AH: Cytokines sing the blues: inflammation and the pathogenesis of depression. Trends Immunol 2006; 27:24–31Google Scholar

31. Roux AVD, Ranjit N, Powell L, Jackson S, Lewis TT, Shea S, Wu C: Psychosocial factors and coronary calcium in adults without clinical cardiovascular disease. Ann Intern Med 2006; 144:822–831Google Scholar

32. Lespérance F, Frasure-Smith N, Talajic M, Bourassa MG: Five-year risk of cardiac mortality in relation to initial severity and one-year changes in depression symptoms after myocardial infarction. Circulation 2002; 105:1049–1053Google Scholar

33. Carney RM, Blumenthal JA, Catellier D, Freedland KE, Berkman LF, Watkins LL, Czajkowski SM, Hayano J, Jaffe AS: Depression as a risk factor for mortality after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2003; 92:1277–1281Google Scholar

34. Drago S, Bergerone S, Anselmino M, Varalda PG, Cascio B, Palumbo L, Angelini G, Trevi PG: Depression in patients with acute myocardial infarction: influence on autonomic nervous system and prognostic role: results of a five-year follow-up study. Int J Cardiol 2007; 115:46–51Google Scholar

35. Bonnet F, Irving K, Terra JL, Nony P, Berthezene F, Moulin P: Anxiety and depression are associated with unhealthy lifestyle in patients at risk of cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis 2005; 178:339–344Google Scholar

36. Gehi A, Haas D, Pipkin S, Whooley MA: Depression and medication adherence in outpatients with coronary heart disease: findings from the Heart and Soul Study. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165:2508–2513Google Scholar

37. Wainwright NWJ, Surtees PG: Childhood adversity, gender, and depression over the life-course. J Affect Disord 2002; 72:33–44Google Scholar

38. Willis-Owen SAG, Turri MG, Munafò MR, Surtees PG, Wainwright NWJ, Brixey RD, Flint J: The serotonin transporter length polymorphism, neuroticism and depression: a comprehensive assessment of association. Biol Psychiatry 2005; 58:451–456Google Scholar

39. Surtees PG, Wainwright NWJ, Willis-Owen SAG, Luben R, Day NE, Flint J: Social adversity, the serotonin transporter (5-HTTLPR) polymorphism and major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2006; 59:224–229Google Scholar

40. Patten SB: International differences in major depression prevalence: what do they mean? J Clin Epidemiol 2003; 56:711–716Google Scholar

41. Waraich P, Goldner EM, Somers JM, Hsu L: Prevalence and incidence studies of mood disorders: a systematic review of the literature. Can J Psychiatry 2004; 49:124–138Google Scholar

42. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, Rush AJ, Walters EE, Wang PS: The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 2003; 289:3095–3105Google Scholar

43. Surtees PG, Wainwright NWJ, Khaw KT: Obesity, confidant support, and functional health: cross-sectional evidence from the EPIC-Norfolk cohort. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2004; 28:748–758Google Scholar

44. Wainwright NWJ, Surtees PG: Places, people, and their physical and mental functional health. J Epidemiol Community Health 2003; 58:333–339Google Scholar

45. Lloyd-Jones DM, Martin DO, Larson MG, Levy D: Accuracy of death certificates for coding coronary heart disease as the cause of death. Ann Intern Med 1998; 129:1020–1026Google Scholar

46. Blumenthal JA, Michos ED, Nasir K: Further improvements in CHD risk prediction for women. JAMA 2007; 297:641–643Google Scholar

47. Lloyd-Jones DM, Leip EP, Larson MG, D’Agostino RB, Beiser A, Wilson PWF, Wolf PA, Levy D: Prediction of lifetime risk for cardiovascular disease by risk factor burden at 50 years of age. Circulation 2006; 113:791–798Google Scholar

48. Skala JA, Freedland KE, Carney RM: Coronary heart disease and depression: a review of recent mechanistic research. Can J Psychiatry 2006; 51:738–745Google Scholar

49. Hunkeler EM, Katon W, Tang L, Williams JW Jr, Kroenke K, Lin EH, Harpole LH, Arean P, Levine S, Grypma LM, Hargreaves WA, Unützer J: Long term outcomes from the IMPACT randomised trial for depressed elderly patients in primary care. BMJ 2006; 332:259–263Google Scholar

50. Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ: Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166:2314–2321Google Scholar

51. Gallo JJ, Bogner HR, Morales KH, Post EP, Lin JY, Bruce ML: The effect of a primary care practice-based depression intervention on mortality in older adults: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2007; 146:689–698Google Scholar