Fertility of Patients With Schizophrenia, Their Siblings, and the General Population: A Cohort Study From 1950 to 1959 in Finland

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Genetic factors are the most important risk factors for schizophrenia. However, despite the fact that patients with schizophrenia have significantly fewer offspring than the general population, schizophrenia persists. The authors investigated whether the siblings of patients with schizophrenia produce more offspring, thereby compensating for the low fertility of the affected individuals. METHOD: From all 870,093 individuals born in Finland from 1950 to 1959, the authors determined how many had schizophrenia or were siblings of schizophrenia patients and how many offspring they had. The population data were obtained from the Population Register Center of Finland, and the National Hospital Discharge Register was used to identify all persons who had been hospitalized because of schizophrenia. Appropriate regression models were used to model age at the birth of the first child, number of children, and proportion of males among offspring. RESULTS: Of the total population, 1.3% were patients with schizophrenia, and 2.8% were their siblings. The mean number of offspring among female siblings was slightly but significantly higher than among women in the general population (1.89 versus 1.83), while the opposite was true for the male siblings (1.57 versus 1.65 among men in the general population). The mean number of offspring among patients with schizophrenia was 0.83 for women and 0.44 for men. CONCLUSIONS: Lower than average fertility among patients with schizophrenia is not compensated for by higher fertility among their siblings. Thus, the persistence of schizophrenia in the general population is not explained by this simple evolutionary mechanism.

Most studies show that schizophrenic patients have a lower rate of marriage and significantly fewer offspring than individuals in the general population (1–10). Although there have been some suggestions that men with schizophrenia who get married have greater than average fertility (11), this increase is not large enough to compensate for the low rate of marriage. Genetic factors are the most important known risk factors of schizophrenia (12), and heritability estimates from the most recent twin studies are as high as 83% (13, 14). Therefore, the fact that schizophrenia persists despite the low fertility or reproductive fitness among persons suffering from it has puzzled scientists (15–18). It has been hypothesized that schizophrenia carries some physiological advantage compared with the general population (15, 16, 19), but no evidence for this hypothesis has been found (16). Another hypothesis is that the role of environmental factors, such as prenatal infections or obstetric complications, in the etiology of schizophrenia has increased over time and compensated for the reduction in genetic factors caused by low fertility (11). A third possible explanation is de novo mutations and imprinting, which could be connected to the higher paternal age of schizophrenic patients (20–23). Finally, it has been suggested that the lower fertility of patients is compensated for by greater fertility among their relatives. Three previous studies (6, 8, 24) have shown greater fertility among parents of patients with schizophrenia than among the general population; these studies were, however, based on fewer than 200 patients plus their relatives.

A fourth study (25) indicated that parents of male patients with a positive family history for schizophrenia had greater than average fertility; this study was based on 73 probands and their relatives.

We set out to test the hypothesis that low fertility among patients with schizophrenia is compensated for by high fertility among their relatives. Because family size varies considerably in different generations, we limited the study to a 10-year birth cohort. We compared the fertility among the total Finnish population born in the 1950s with the fertility among individuals born in the 1950s with at least one hospitalization because of schizophrenia, according to the National Hospital Discharge Register, and with fertility among their siblings born in the same years.

Method

The study population consisted of all individuals born in Finland from 1950 to 1959. Persons born outside Finland or of unknown birthplace were excluded. Individuals who had had at least one hospitalization because of schizophrenia between Jan. 1, 1969, and Jan. 1, 1992, were identified from the National Hospital Discharge Register. Schizophrenia was defined as a 295 diagnosis code according to ICD-8 and ICD-9, which includes schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, and schizoaffective disorder. Information on their siblings was obtained from the Population Register Center and was linked by using the personal identification numbers, which code the date of birth and sex and are unique for each person.

The year of birth and sex of all offspring of the study population until year 2000 were obtained from the Population Register Center. Thus, for all individuals of the study population we had the following data: year of birth, sex, year of birth and sex of all offspring, and a categorical variable indicating whether the individual was a person with schizophrenia, a sibling of a person with schizophrenia, or neither.

The following response variables were used: age when the first child was born, number of offspring, number of offspring for each person with at least one child, an indicator variable for the presence of at least one offspring, and the proportion of males among the offspring. We used a linear regression model for age at the birth of the first child, a Poisson regression model for number of children, and a logistic regression model for proportions (26). Categorical birth year (1950–1959) and study group (schizophrenic, sibling, or general population) were used as explanatory variables. Separate models were fitted for male and female subjects. The significance of the explanatory variables was tested by using likelihood ratio statistics. The significance of differences between subgroups (schizophrenic, sibling, and general population) was tested by using Wald-type tests. All calculations were carried out by means of the S-PLUS program (27).

Results

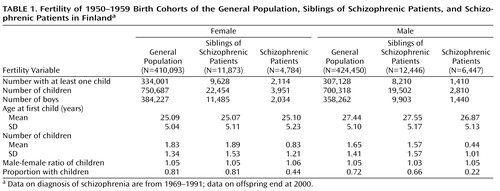

We gathered information on the number of offspring of all 870,093 individuals born in Finland from 1950 to 1959 (Table 1). Of the total population, 1.3% had schizophrenia, and 2.8% were siblings of patients with schizophrenia. Although the observed prevalence is relatively high, it is in line with earlier Finnish findings, such as the 1.3% in the Mini Finland Health Survey (28) and 2.0% in a twin study (14).

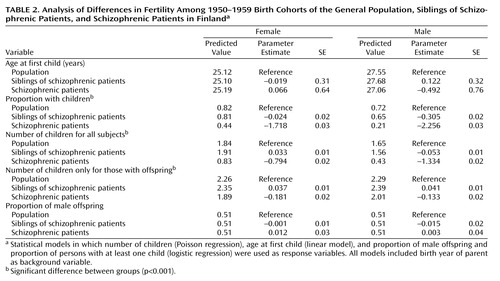

As shown in Table 2, the proportion of individuals with at least one child was clearly lowest among the patients with schizophrenia of both sexes (women: χ2=3263.22, df=1, p<0.001; men: χ2=7264.72, df=1, p<0.001). There was no significant difference between the general population and the female siblings of schizophrenic patients (χ2=1.03, df=1, p=0.31), but among males the proportion of individuals with at least one child was lower among siblings (χ2=251.13, df=1, p<0.001). The number of offspring was highest among female siblings of schizophrenic patients, although the absolute difference from the general population was only 0.03 (χ2=23.29, df=1, p<0.001); for male siblings the number of offspring was 0.05 lower (χ2=52.69, df=1, p<0.001). When the numbers of offspring were compared only among subjects with at least one child, the siblings of schizophrenic patients had significantly higher numbers, both for women (χ2=29.66, df=1, p<0.001) and for men (χ2=31.78, df=1, p<0.001). There were no significant differences in the proportion of male offspring among the three groups (Table 2).

Discussion

The patients with schizophrenia had, on average, one child less than individuals in the general population, as found in several earlier studies (2, 5–10). Among female siblings of patients with schizophrenia, the number of offspring was slightly higher than among women in the general population, while male siblings had fewer offspring than men in the general population. At first sight, our results may seem to provide weak evidence for the hypothesis that the lower fertility of patients with schizophrenia is compensated for by more children among their relatives. Three earlier studies (6, 8, 24), although based on much smaller study groups and comparing fertility among parents, not among siblings, provided some support for this hypothesis. However, a simple calculation based on the predicted number of offspring among women in our study shows that this compensation is insufficient. Assume that the cumulative lifetime incidence of schizophrenia is 1% and that every family has three offspring, making 2% of the population siblings of patients with schizophrenia. Combine these assumptions with predictions from the data in Table 2 on the numbers of children for all female subjects. The result is that in the next generation, 2.1% of the offspring are produced by siblings of patients with schizophrenia; this calculation is based on the formula (0.02×1.91)/([0.97×1.84]+[0.02×1.91]+[0.01×0.83]). The patients with schizophrenia would produce 0.5% of the offspring: (0.01×0.83)/([0.97×1.84]+[0.02×1.91]+[0.01×0.83]). This means that the proportion of genes inherited from these families would be lower in the new generation than in the previous one.

A recent report (29) suggesting that the risk of schizophrenia is associated with increasing paternal age lends some support to the hypothesis that schizophrenia may be partly due to de novo mutation of the paternal germ cells. Our study findings are not in conflict with this view: new mutations could explain the persistence of schizophrenia despite lower fertility of schizophrenic individuals.

On the other hand, it may be that evolutionary selection mechanisms working against schizophrenia-related genes are related to environmental factors. That is, it is possible that the genes provided some physiological advantage in the past but with a changing environment no longer do so. The observed decline in the incidence of schizophrenia in Finland between 1954 and 1965 (30) could have been caused by changes in these factors. For example, our study on regional differences in the incidence of schizophrenia in Finland (31) showed that areas that had higher neonatal mortality rates used to have higher incidences of schizophrenia. If this was caused by greater robustness associated with the schizophrenia genotype, leading to increased survival, as has been suggested (32), this advantage may have disappeared when factors that caused the higher neonatal mortality rate disappeared.

It is also possible that fertility among patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorder or among their relatives is high, thereby explaining the persistence of genes predisposing to schizophrenia. At least, the reproductive fitness among persons having schizotypal personality disorder is not lower than average (33).

Finally, it may be that low fertility is a recent phenomenon related to, for example, culturally delayed marriage (17). Consistent with this view are findings from a British case-control study from London (34), which showed that the marital rate and fertility of patients with schizophrenia who were white British or of Caribbean origin were lower than those of comparison subjects, but no such difference was observed for patients of Asian origin. This means that our results may not be generalizable to other populations or even to other Finnish birth cohorts, as cultural and economical factors probably are the most important determinants of the number of offspring among humans.

The National Hospital Discharge Register, used in this study, has been found to be a reliable and accurate tool in epidemiological research (35). The reliability of diagnoses of schizophrenia in the Hospital Discharge Register has been assessed in several studies (14, 36). These studies show that Finnish psychiatrists tend to apply a narrow definition of schizophrenia in their clinical practice, with more of a tendency toward false negative than false positive diagnoses. Therefore, mild cases of schizophrenia are not included. The main limitation of our study is that we dealt only with the fertility of one generation. From an evolutionary perspective, it would be important to study fertility in two or more successive generations. It should be noted that the findings for the female subjects are more meaningful, because there is always more uncertainty about paternity. Another aspect is that all of the female subjects were followed up close to the end of their reproductive life (at least age 41), thus providing more complete information on overall fertility.

These findings indicate that the genetic basis of schizophrenia is still unresolved, and it seems that no simple evolutionary mechanism can explain the persistence of genes connected to schizophrenia in the population.

|

|

Received June 12, 2002; revision received Sept. 12, 2002; accepted Sept. 19, 2002. From the Kansanterveyslaitos, National Public Health Institute. Address reprint requests to Dr. Haukka, Kansanterveyslaitos, National Public Health Institute, Mannerheimintie 160, FIN-00300 Helsinki, Finland; [email protected] (e-mail).

1. Essen-Möller E: Mating and fertility patterns in families with schizophrenia. Eugenics Q 1959; 6:142-147Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Slater E, Hare H, Price J: Marriage and fertility of psychiatric patients compared with national data. Soc Biol 1971; 18:S60-S73Google Scholar

3. Haverkamp F, Propping P, Hilger T: Is there an increase of reproductive rates in schizophrenics? I: critical review of the literature. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr 1982; 232:439-450Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Kendler KS, McGuire M, Gruenberg AM, O’Hare A, Spellman M, Walsh D: The Roscommon Family Study, I: methods, diagnosis of probands, and risk of schizophrenia in relatives. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:527-540Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Nanko S, Moridaira J: Reproductive rates in schizophrenic outpatients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1993; 87:400-404Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Fananas L, Bertranpetit J: Reproductive rates in families of schizophrenic patients in a case-control study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1995; 91:202-204Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Nimgaonkar VL, Ward SE, Agarde H, Weston N, Ganguli R: Fertility in schizophrenia: results from a contemporary US cohort. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1997; 95:364-369Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Srinivasan TN, Padmavati R: Fertility and schizophrenia: evidence for increased fertility in the relatives of schizophrenic patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1997; 96:260-264Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Nimgaonkar VL: Reduced fertility in schizophrenia: here to stay? Acta Psychiatr Scand 1998; 98:348-353Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. McGrath JJ, Hearle J, Jenner L, Plant K, Drummond A, Barkla JM: The fertility and fecundity of patients with psychoses. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1999; 99:441-446Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Lane A, Byrne M, Mulvany F, Kinsella A, Waddington JL, Walsh D, Larkin C, O’Callaghan E: Reproductive behaviour in schizophrenia relative to other mental disorders: evidence for increased fertility in men despite decreased marital rate. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1995; 91:222-228Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Owen MJ, Cardno AG: Psychiatric genetics: progress, problems, and potential. Lancet 1999; 354(suppl 1):11-14Google Scholar

13. Cardno AG, Marshall EJ, Coid B, Macdonald AM, Ribchester TR, Davies NJ, Venturi P, Jones LA, Lewis SW, Sham PC, Gottesman II, Farmer AE, McGuffin P, Reveley AM, Murray R: Heritability estimates for psychotic disorders: the Maudsley twin psychosis series. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:162-168Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Cannon T, Kaprio J, Lönnqvist J, Huttunen M, Koskenvuo M: The genetic epidemiology of schizophrenia in a Finnish twin cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:67-74Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Huxley JE, Mayr G, Osmond H: Schizophrenia as genetic morphism. Nature 1964; 204:220-221Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Vogel HP: Fertility and sibship size in a psychiatric patient population: a comparison with national census data. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1979; 60:483-503Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Hare E: Schizophrenia as a recent disease. Br J Psychiatry 1988; 153:521-531Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Crow T: A continuum of psychosis, one gene, and not much else—the case for homogeneity. Schizophr Res 1995; 17:135-145Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Karlsson JL: Inheritance of schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1974; 247:1-116Medline, Google Scholar

20. Böök JA: Schizophrenia as gene mutation. Acta Genet Stat Med 1953; 4:133-139Medline, Google Scholar

21. Hare EH, Moran P: Raised parental age in psychiatric patients: evidence for a constitutional hypothesis. Br J Psychiatry 1979; 134:169-177Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Raschka LB: Paternal age and schizophrenia in dizygotic twins (letter). Br J Psychiatry 2000; 176:400-401Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Malaspina D: Paternal factors and schizophrenia risk: de novo mutations and imprinting. Schizophr Bull 2001; 27:379-393Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Avila M, Thaker G, Adami H: Genetic epidemiology and schizophrenia: a study of reproductive fitness. Schizophr Res 2001; 47:233-241Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Waddington JL, Youssef HA: Familial-genetic and reproductive epidemiology of schizophrenia in rural Ireland: age at onset, familial morbid risk and parental fertility. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1996; 93:62-68Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. McCullagh P, Nelder JA: Generalized Linear Models, 2nd ed. London, Chapman & Hall, 1994Google Scholar

27. S-Plus 5 for UNIX Guide to Statistics. Seattle, MathSoft, Data Analysis Products Division, 1998Google Scholar

28. Lehtinen V, Joukamaa M, Lahtela K, Raitasalo R, Jyrkinen E, Maatela J, Aromaa A: Prevalence of mental disorders among adults in Finland: basic results from the Mini Finland Health Survey. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1990; 81:418-425Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Malaspina D, Harlap S, Fennig S, Heiman D, Nahon D, Feldman D, Susser E: Advancing paternal age and the risk of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:361-367Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Suvisaari J, Haukka J, Tanskanen A, Lönnqvist J: Decline in the incidence of schizophrenia in Finnish cohort born from 1954 to 1965. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:733-740Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Haukka J, Suvisaari J, Varilo T, Lönnqvist J: Regional variation in the incidence of schizophrenia in Finland: a study of birth cohorts born from 1950 to 1969. Psychol Med 2001; 31:1045-1053Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Torrey EF, Miller J, Yolken RH: Seasonality of births in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a review of the literature. Schizophr Res 1997; 28:1-38Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Battaglia M, Bellodi L: Familial risks and reproductive fitness in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1996; 22:191-195Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Hutchinson G, Bhugra D, Mallett R, Burnett R, Corrida B, Leff J: Fertility and marital rates in first-onset schizophrenia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1999; 34:617-621Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Keskimäki I, Aro S: Accuracy of data on diagnoses, procedures and accidents in the Finnish Hospital Discharge Register. Int J Health Sci 1991; 2:15-21Google Scholar

36. Pakaslahti A: On the diagnosis of schizophrenic psychoses in clinical practice. Psychiatria Fennica 1987; 18:63-72Google Scholar