Psychiatric Disability Among Tortured Bhutanese Refugees in Nepal

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Most refugees live in low-income countries. There is a lack of data on psychiatric disability among such refugees. The authors compared psychiatric disability in tortured and nontortured Bhutanese refugees living in Nepal and examined factors associated with psychiatric disability among the tortured refugees. METHOD: A cross-sectional survey was conducted among 418 tortured and 392 nontortured Bhutanese refugees, matched for age and gender. The Composite International Diagnostic Interview, version 2.1, and the World Health Organization Short Disability Assessment Schedule were used to measure ICD-10 psychiatric disorders and disability, respectively. RESULTS: Approximately one in five tortured and nontortured Bhutanese refugees were found to be disabled. Posttraumatic stress disorder, specific phobia, and present physical disease were identified as factors associated with disability among the tortured refugees. On the other hand, present physical disease, greater age, and generalized anxiety disorder were associated with disability among the nontortured group. CONCLUSIONS: These findings show that the tortured and nontortured refugees were equally likely to be disabled. Different sets of predictors were identified among tortured and nontortured refugees, indicating the need for comprehensive psychiatric assessment of both tortured and nontortured refugees in clinical practice.

Studies among refugees and postconflict populations have revealed elevated prevalences of symptoms of psychiatric disorders, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), affective disorders, and dissociative disorders (1–4). In addition, a limited number of studies, in refugee (5, 6) and in general (7, 8) populations, have examined the relationship between psychiatric disorders and associated disability. These studies have identified an independent association between psychiatric disorders and disability (5–9). A study of Bosnian refugees (5) indicated that older age, lack of education, and chronic medical illness were associated with disability, while gender, cumulative trauma, and torture experiences were not associated. A follow-up study of the same group (6) demonstrated that almost one-half of the 25% who had met disability criteria in the earlier survey remained disabled after 3 years. In a prospective study among Vietnamese refugees living in Norway, 15% of the respondents reported reduced levels of activity during the last 2 weeks (10).

Most of the available literature on refugee mental health is limited to refugees living in the West (11) despite the fact that the majority of refugees live in low-income countries. We know of no published research on refugees living in low-income countries that has examined psychiatric disability and associated factors. Systematic study of the effects of torture on such refugees has been difficult (12), largely because of problems in organizing controlled studies involving randomly sampled torture survivors. A study involving a random sample of Bhutanese refugees (13) indicated that torture survivors were more likely to have symptoms of PTSD, clinical anxiety, and clinical depression.

We conducted a follow-up study on the same group of Bhutanese refugees (14). We found that the torture survivors had higher lifetime and 12-month rates of ICD-10 psychiatric disorders. Tortured refugees, compared to nontortured refugees, were more likely to report 12-month ICD-10 PTSD (43% versus 4%), dissociative (conversion) disorders (18% versus 3%), and persistent somatoform pain disorder (51% versus 28%). The most common 12-month ICD-10 disorder among nontortured refugees was persistent somatoform pain disorder (28%), followed by specific phobia (26%). Almost three out of four of the tortured subjects and almost one-half of the nontortured refugees had had one disorder in the preceding 12 months, indicating a high rate of psychopathology among this population. In the present study we 1) tested the hypothesis that the rate of psychiatric disability is higher among tortured Bhutanese refugees than among nontortured refugees living in Nepal and 2) identified factors associated with psychiatric disability among tortured refugees.

Method

Participants

Details of our methods, including the historical background of the Bhutanese refugees, have been described previously (14). We approached a representative sample of 526 tortured adult refugees matched with 526 nontortured refugees between March 20 and July 31, 1997; all of them had been interviewed in 1995 (13). The Center for Victims of Torture Nepal, a nongovernmental organization that was responsible for providing medical and psychosocial care to more than 1,200 tortured Bhutanese refugees, carried out this survey in collaboration with the Transcultural Psychosocial Organization as part of the Multisite Impact of Human-Made Disaster Study. The staff of the Center for Victims of Torture Nepal conducted a hut-to-hut survey in 1994 and identified 2,331 Bhutanese adult refugees who reported a history of physical torture. The 526 tortured participants were randomly selected from that list of 2,331 registered tortured adult refugees, and a comparison group of 526 nontortured participants were selected from neighbors of the tortured participants. The tortured and nontortured refugees were matched for age and gender. A difference in age of 10 years or fewer was accepted as an age match.

We were able to approach 946 (89.9%) of the 1,052 refugees in our sampling frame during the period in which we were allowed to collect the data. Of the 946 approached refugees, 879 (92.9%) were interviewed, 32 refused, 20 were out of the camp, four were not found, five had died, and six were too disabled by mental or physical illness to attend the interview. Of the 879 interviews, 20 were not completed because of mental state problems or deafness. Moreover, the results of 49 interviews were discarded because the interviewees were not in our sampling frame and had been interviewed by mistake. The remaining 810 participants consisted of 418 tortured and 392 nontortured refugees.

Instruments

We used the depression, specific phobias, dissociative, PTSD, persistent somatoform pain, and generalized anxiety disorder modules of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview, version 2.1 (15). We studied ICD-10 disorders because, in contrast to DSM-IV, ICD-10 has been specifically developed for international use. International field testing in a wide range of cultures and settings has shown that the modules of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview that were included in this study have excellent interrater reliability and acceptable-to-good test-retest reliability (16).

Disability was measured with the World Health Organization (WHO) Short Disability Assessment Schedule (17). This instrument is a short version of the WHO Psychiatric Disability Assessment Schedule, which has been used for cross-cultural comparison of psychiatric disability after extensive field trials and studies in more than 20 countries (18–20). The WHO Short Disability Assessment Schedule is a semistructured interview, and two local physicians, familiar with the context, rated disability in four domains: personal care (washing, shaving, dressing, maintaining hygiene), social function (social activities and relationships with neighbors), household activity (cooking, cleaning, having meals together, decision making), and occupational activity (work or study productivity, relations with others during work or study).

Disability status was given to all those who were found to have any impairment in their expected roles in any domain of assessed functions. A dichotomous variable “any disability” (here onward referred to as “disability”) was created and, consistent with the conceptualization of the WHO Psychiatric Disability Assessment Schedule, defined as any restriction or lack of ability (resulting from a loss in function) to perform an activity in the manner or within the range considered normal for an individual in his or her sociocultural setting (17, 18).

On the basis of a brief medical investigation, the physician assessed the presence of significant current and past physical diseases, including diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, head injury, meningitis, encephalitis, and thyroid dysfunction.

Procedures

The Composite International Diagnostic Interview was systematically translated and implemented after pilot testing, as discussed in detail elsewhere (21). The interviewers were two male physicians and three male and two female undergraduate students. They all received three weeks of training in administering the instruments. We anticipated the challenge of female respondents’ reluctance to answer private questions related to sex, due to cultural barriers. Accordingly, we assigned female interviewers to all female respondents. The interviews consisted of a medical section and a nonmedical section. The medical section, administered to all participants by one of the two physicians, consisted of the somatoform and dissociative disorders section of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview, a medical history, the WHO Short Disability Assessment Schedule, and a brief physical examination. The five lay interviewers administered all other measures.

All interviews took place in a confidential environment. Because most of our respondents were illiterate, we asked for verbal informed consent after explaining briefly our research methods and aims. Obtained consent was recorded on paper. We followed the Declaration of Helsinki’s recommendations guiding ethical research (22).

Statistical Analysis

We used chi-square analysis and Student’s t test to examine univariate differences in disability and sociodemographic variables between the tortured and nontortured groups. We are reporting two-tailed test values, and we present Yates-corrected chi-square values for all two-by-two tables. Values for Student’s t tests are reported according to the results of testing the equality-of-variance assumption.

We assessed the following possible factors associated with disability: gender, age, marital status, education, religion, political activity, economic status, present physical disease, time since displacement, duration of torture, time since torture, and 12-month ICD-10 psychiatric disorders. With the exception of the variable age, continuous variables were dichotomized with the median value as the cutoff point. Associations between disability and all other possible factors among the tortured refugees were examined through calculation of odds ratios by using univariate logistic regression analyses. Main effects were tested in multivariate logistic regression analysis by simultaneously entering all of the variables that had shown some association (p<0.10) with disability in the univariate analyses. A separate multivariate analysis was run by adding to the model the interaction terms created for the interactions among age, gender, and the three predictor variables that were significant in the multivariate testing of main effects. We used multicollinearity diagnostic tests to check for collinearity among the independent variables in the model. Multicollinearity diagnostics indicated a conditioning index smaller than 30 and at most one variable proportion larger than 0.5 for a given root number, thus suggesting the absence of multicollinearity in these regression analyses (23). For univariate analyses, significance was set at 0.005 to reduce chance significance caused by multiple tests. Significance was set at 0.05 for multivariate analyses. All analyses were repeated by centering the continuous data and entering standardized variables (z scores) and interactions computed from the z scores, and the pattern of results stayed the same (data not reported). Data were analyzed by commercially available software (24).

Results

The details on types of torture have been described previously (13). Briefly, the most commonly reported torture techniques were severe beating (97.1%), threats (89.0%), humiliations (79.2%), forced incongruent acts (e.g., asking a Hindu to eat beef, which is against the religious norms) (66.3%), social isolation (54.3%), and nutritional (52.2%) and sleep (51.9%) deprivation. The mean duration of torture was 21 days (SD=83). The time since torture and time since displacement were on average 6.0 years (SD=0.9) and 5.0 years (SD=0.7), respectively.

The age of the sample ranged between 21 and 85 years, with a mean of 44.3 (SD=12.5). Of the 810 refugees, 68.3% were illiterate, and 89.9% were married. Four out of five respondents (79.9%) were Hindus, and the remaining subjects were mainly Buddhist (14.9%). As a result of matching, the tortured and nontortured groups in the sample were similar in terms of age (mean=44.5 years, SD=12.4, versus mean=44.1, SD=12.6) (t=0.53, df=808, p=0.60) and gender (74.5% and 77.5% of the nontortured and tortured groups were men, respectively) (χ2=1.01, df=1, p=0.31). There were more Hindus among the tortured group than among the nontortured group (83.5% versus 76.0%) (χ2=7.03, df=1, p=0.008). More nontortured refugees reported present physical disease during the interview (37.0% versus 27.0%) (χ2=9.24, df=1, p=0.002), probably because the tortured refugees had better access to health services (25). The tortured and nontortured groups were similar in terms of marital status (90.0% and 88.5% lived with spouses, respectively) (χ2=0.43, df=1, p=0.51), employment status (92.6% and 93.1% were unemployed) (χ2=0.08, df=1, p=0.77), education (32.1% and 32.7% were literate) (χ2=0.33, df=1, p=0.86), and past physical disease (25.6% and 30.6%, respectively) (χ2=2.52, df=1, p=0.11).

Disability and Disorders

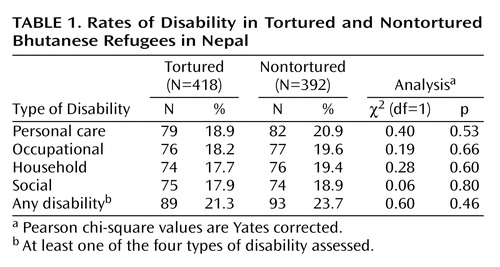

There was no significant difference between the tortured and nontortured groups in terms of disability detected in the four domains (Table 1). The physicians identified disability in 21.3% of the tortured refugees and 23.7% of the nontortured refugees. Furthermore, out of the total 182 disabled, 127 (69.8%) were rated as disabled in all four domains, 20 (11.0%) in three domains, 10 (5.5%) in two domains, and 25 (13.7%) in one domain; the mean number of disabilities was 3.4 (SD=1.1). Among the disabled, only 15.7% (N=14) in the tortured group and 10.8% (N=10) in the nontortured group had been disabled for less than 1 year. The intraclass correlation coefficient for the correlation among the four different domains of disability was 0.86, and the 95% confidence interval (CI) was 0.83–0.87 (p<0.001). On the other hand, out of the total 499 respondents who had at least one 12-month ICD-10 diagnosis, there were 238 (47.7%) with only one disorder, 160 (32.1%) with two disorders, 67 (13.4%) with three disorders, 30 (6.0%) with four disorders, and four (0.8%) with five disorders; the mean number of disorders was 1.8 (SD=0.9).

Factors Associated With Disability

Table 2 displays odds ratios for disability among the tortured refugees, based on univariate logistic regression analyses. Assessed disability was not associated with gender, age, marital status, economic status, religion, or political activity (p>0.005 for all tests of association). Having formal education appeared to protect against disability. Those who had present physical disease were at much higher risk for disability. Torture-related variables—duration of torture, time since torture, and time since displacement—were not found to be associated with disability.

Among the tortured respondents, we also assessed bivariate associations of disability with 12-month ICD-10 diagnoses of generalized anxiety, PTSD, persistent somatoform pain, specific phobia, dissociative disorder, and depression. Results of univariate logistic regression analyses are shown in Table 3. Except for generalized anxiety disorder and depression, we found bivariate associations between disability and all assessed psychiatric disorders. The results also indicate a dose-response relationship between number of psychiatric disorders and associated disability, because the odds for disability increased fourfold for those having more than three psychiatric disorders in the past 12 months.

Multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted to adjust the odds of disability for each other by simultaneously entering in the model the following variables, which had some association (p<0.10) in the univariate analyses: gender, age, education, religion, political activity, present physical disease, PTSD, persistent somatoform pain, specific phobia, dissociative disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and depression. Table 4 shows that the odds of disability for tortured refugees were increased if they had present physical disease, PTSD, or specific phobia. The pattern of results stayed the same when we added the terms for interactions among age, gender, and the three predictor variables to the multivariate model. None of the added interaction terms was significant at the 0.05 level. Similar multivariate analyses for the nontortured refugees suggested that current physical disease (odds ratio=3.3, 95% CI=1.9–5.7, p<0.0001), greater age (odds ratio=2.3, 95% CI=1.1–5.1, p=0.04), and generalized anxiety disorder (odds ratio=3.2, 95% CI=1.2–8.9, p=0.02) were associated with disability.

Discussion

The tortured and nontortured refugees had similar patterns of disability in the four different domains of disability: personal care, family, household, and social activities. However, except for present physical diseases, other factors associated with the disability differed between the groups. Approximately one in five tortured and nontortured refugees was disabled. Even though we were measuring disability with respect to these four domains, we observed that an individual who scored a certain degree of disability for one domain was likely to score almost the same degree of disability for the other domains as well.

Time since trauma was not associated with disability status. This may be because there was a lack of variation among the refugees in terms of the time since the torture and displacement occurred. Factors found to be associated with disability among the tortured refugees were PTSD, present health status, and specific phobia, after we controlled for all other sociodemographic and disease variables. The association between PTSD and disability has been previously shown both among Vietnam veterans in the United States (25) and among Bosnian refugees in Croatia (5). The association of present health status with disability is consistent with the finding among Bosnian refugees, for whom perceived health status was reported to predict disability (5). Other researchers (26, 27) have found an association of disability with social phobia. However, as far as we know, an association with specific phobia in a refugee population has not been previously reported. This unexpected finding warrants further study.

In spite of our earlier finding that the tortured group had more psychiatric morbidity than the nontortured comparison group (14), we detected no difference in disability. The finding of no association between torture status and disability has also been found among Bosnian refugees (6). The lack of difference in disability scores may be explained by the different risk factors for disability in the tortured and nontortured groups. Moreover, among the tortured refugees, greater disability associated with greater mental disease may be offset by reduced disability due to less physical disease, which may have been treated as a result of the torture survivors’ better access to medical services for several years (28, 29). This latter explanation underlines the importance of providing quality health and mental health services to all refugees, in particular to torture survivors, who are at greater risk of psychiatric disorder, to enable these survivors to perform normal activities of life without impairment.

Except for religion, both the tortured and nontortured groups were well matched for demographic characteristics. There were more Hindus in the tortured group, possibly because the ethnic group persecuted by authorities in Bhutan is mostly Hindu.

This study has the following limitations. We collected these data several years after the participants became refugees, and evaluators were not blinded regarding the torture status of our respondents. Nevertheless, the lack of masking does not necessarily bias the results, because the groups scored similarly on the disability measure. We used a highly similar comparison group, yet the two groups might have differed on variables that were not assessed. Moreover, disability was measured with the WHO Short Disability Assessment Schedule, which, in contrast to the WHO Psychiatric Disability Assessment Schedule and WHO Psychiatric Disability Assessment Schedule II, has not been validated. Furthermore, because of restrictions related to time-limited permission to do the study, we did not study the reliability of the disability measure. Less than perfect reliability attenuates correlation and reduces statistical power. Any null findings must be viewed in light of a lack of information on the local reliability of the WHO Short Disability Assessment Schedule. Furthermore, the sample size, although substantial, does not provide enough power to allow testing of all possible interactions between possible predictors. However, we tested and found no significant interactions with age and gender. Finally, the sample somewhat underrepresented disability, because 3% of all approached participants had died, were too disabled by mental or physical illness to attend the interview, or provided incomplete interviews because of mental state problems or deafness. Further investigations are needed to clarify the relationships among trauma, disorder, and disability. In conclusion, comprehensive psychiatric assessment and quality health services are required for both tortured and nontortured refugees to prevent disability.

|

|

|

|

Received Oct. 1, 2001; revisions received May 16 and Nov. 15, 2002; accepted Feb. 12, 2003. From the Center for Victims of Torture Nepal, Kathmandu, Nepal; the Department of International Health and the Psychosocial Center for Refugees, Department of Psychiatry, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway; and the Transcultural Psychosocial Organization, Amsterdam. Address reprint requests to Dr. Thapa, Department of International Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oslo, P.O. Box 1130 Blindern, N-0317, Oslo, Norway; [email protected] (e-mail).The authors thank Leiv Sandvik, Ph.D., Ivan Komproe, Ph.D., and Magne Thoresen, Ph.D., for their contributions to the statistical analyses.

1. Goldfeld AE, Mollica RF, Pesavento BH, Faraone S: The physical and psychological sequelae of torture. JAMA 1988; 259:2725–2729Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Ager A: Mental Health in Refugee Populations: A Review. Boston, Harvard Center for the Study of Culture and Medicine, 1993Google Scholar

3. Hauff E, Vaglum P: Organized violence and the stress of exile: predictors of mental health in a community cohort of Vietnamese refugees three years after resettlements. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 166:360–367Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. de Jong JT, Komproe IH, Van Ommeren M, El Masri ME, Araya M, Khaled N, van De Put W, Somasundaram D: Lifetime events and posttraumatic stress disorder in 4 postconflict settings. JAMA 2001; 286:555–562Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Mollica RF, McInnes K, Sarajlic N, Lavelle J, Sarajlic I, Massagli MP: Disability associated with psychiatric comorbidity and health status in Bosnian refugees living in Croatia. JAMA 1999; 282:433–439Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Mollica RF, Sarajlic N, Chernoff M, Lavelle J, Vukovic IS, Massagli MP: Longitudinal study of psychiatric symptoms, disability, mortality, and immigration among Bosnian refugees. JAMA 2001; 286:546–554Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Berardi D, Berti Ceroni G, Leggieri G, Rucci P, Ustun B, Ferrari G: Mental, physical and functional status in primary care attenders. Int J Psychiatry Med 1999; 29:133–148Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Ormel J, VonKorff M, Ustun B, Pini S, Korten A, Oldehinkel T: Common mental disorders and disability across cultures: results from the WHO Collaborative Study on Psychological Problems in General Health Care. JAMA 1994; 272:1741–1748Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Druss BG, Marcus SC, Rosenheck RA, Olfson M, Tanielian T, Pincus H: Understanding disability in mental and general medical conditions. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1485–1491Link, Google Scholar

10. Hauff E, Vaglum P: Physician utilization among refugees with psychiatric disorders: a need for outreach interventions. J Refug Stud 1997; 10:154–164Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Desjaralais R, Eisenberg L, Good B, Kleinman A: World Mental Health: Problems and Priorities in Low-Income Countries. New York, Oxford University Press, 1995Google Scholar

12. Pedersen HD: The controlled study of torture victims: epidemiological considerations and some future aspects. Scand J Soc Med 1989; 17:13–20Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Shrestha NM, Sharma B, Van Ommeren M, Regmi S, Makaju R, Komproe I, Shrestha GB, de Jong JTVM: Impact of torture on refugees displaced within the developing world: symptomatology among Bhutanese refugees in Nepal. JAMA 1998; 280:443–448Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Van Ommeren M, de Jong JTVM, Sharma B, Komproe I, Thapa SB, Cardena E: Psychiatric disorders among tortured Bhutanese refugees in Nepal. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:475–482Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. World Health Organization: Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), version 2.1. Geneva, WHO, 1997Google Scholar

16. Andrews G, Peters L: The psychometric properties of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1998; 32:80–88Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Janca A, Kastrup M, Katsching H, Lopez-Ibor JJ, Mezzich J, Sartorius N: The World Health Organization Short Disability Assessment Schedule (WHO DAS-S): a tool for the assessment of difficulties in selected areas of functioning of patients with mental disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1996; 31:349–354Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. World Health Organization: WHO Psychiatric Disability Assessment Schedule (WHO/DAS) With a Guide to Its Use. Geneva, WHO, 1988Google Scholar

19. Rahman MB, Indran SK: Disability in schizophrenia and mood disorders in a developing country. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1997; 32:387–390Medline, Google Scholar

20. Marneros A, Deister A, Rohde A, Steinmeyer EM, Junemann H: Unipolar and bipolar schizoaffective disorders: a comparative study, III: long-term outcome. Eur Arch Psychiatry Neurol Sci 1989; 239:171–176Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Van Ommeren M, Sharma B, Thapa S, Makaju R, Prasain D, Bhattarai R, de Jong JTVM: Preparing instruments for transcultural research: use of the Translation Monitoring Form with Nepali-speaking Bhutanese refugees. Transcult Psychiatry 1999; 36:285–301Crossref, Google Scholar

22. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: recommendations guiding physicians in biomedical research involving human subjects. JAMA 1997; 277:925–926Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS: Using Multivariate Statistics, 3rd ed. New York, HarperCollins, 1996Google Scholar

24. SPSS for Windows, version 9.0. Chicago, SPSS, 1999Google Scholar

25. Zatzick DF, Marmar CR, Weiss DS, Browner WS, Metzler TJ, Golding JM, Stewart A, Schlenger WE, Wells KB: Posttraumatic stress disorder and functioning and quality of life outcomes in a nationally representative sample of male Vietnam veterans. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1690–1695Link, Google Scholar

26. Stein MB, Kein YM: Disability and quality of life in social phobia: epidemiological findings. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1606–1613; correction, 2000; 157:2075Google Scholar

27. Olfson M, Fireman B, Weissman MM, Leon AC, Sheehan D, Kathol RG, Hoven C, Farber L: Mental disorders and disability among patients in a primary care group practice. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1734–1740Link, Google Scholar

28. Van Ommeren M, Sharma B, Prasain D, Poudyal BN: Addressing human rights violations, in Trauma, War, and Violence: Public Mental Health in Socio-Cultural Context. Edited by de Jong JTVM. New York, Plenum, 2002, pp 259–283Google Scholar

29. Sharma B, Van Ommeren M: Preventing torture and rehabilitating survivors in Nepal. Transcult Psychiatry 1998; 35:85–97Crossref, Google Scholar