Patient and Psychiatrist Ratings of Hypothetical Schizophrenia Research Protocols: Assessment of Harm Potential and Factors Influencing Participation Decisions

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: A central ethical issue in schizophrenia research is whether participants are able to provide informed consent, particularly for protocols entailing medication washouts or placebo treatments. Few data show how patients with schizophrenia and psychiatrists assess such scientific designs regarding potential harm, willingness to participate, and the relative influence of clinicians, family members, and financial incentives upon participation decisions. METHOD: In this preliminary study, structured interviews were conducted with schizophrenia patients (N=59), and parallel surveys were completed by attending and resident psychiatrists (N=70). Four hypothetical research protocols were rated. Patients were asked about their own views; psychiatrists provided both their personal views and predictions of patient views. RESULTS: Patients and psychiatrists both perceived substantially different levels of harm across the four protocols, identifying significantly greater harm for medication washouts or placebo treatments. Participants were less willing to enroll in protocols perceived as more harmful. Schizophrenia patients found enrollment decisions relatively easy. Patients and psychiatrists indicated that doctor recommendations, monetary incentives, and, to a lesser extent, family preferences had a mild influence on participation decisions. CONCLUSIONS: Given hypothetical protocols with variable design elements, schizophrenia patients and psychiatrists made meaningful and discerning harm assessments and participation decisions. These findings suggest that schizophrenia patients may have strengths in the research consent process that may not be fully recognized. The impact of outside influences upon research enrollment decisions remains uncertain. While psychiatrists were often accurate in predicting patient responses, data suggest the importance of clarifying views of individual patients regarding specific protocols.

Schizophrenia research poses significant challenges, and conscientious individuals hold remarkably varying opinions on whether such work can be performed ethically. A central issue in this discussion is whether people with serious mental illnesses can provide fully informed and voluntary consent for research participation (1, 2). In particular, significant concern has arisen over whether schizophrenia patients are able to accurately assess the potential harms associated with specific experimental designs (2, 3). Studies that include a medication washout or a placebo treatment condition have received special scrutiny by the National Institute of Mental Health, the President’s National Bioethics Advisory Commission, the national media, and consumer groups (2, 4–6). Attention to these linked ethical and scientific considerations has been important to our society’s efforts to define a new and more rigorous approach to safeguarding potentially vulnerable research participants (1, 7, 8).

Careful consideration of the ethical dimensions of psychiatric research is indeed merited on the basis of empirical evidence gathered over three decades (9). This work suggests that mentally ill individuals experience greater barriers to informed consent than do many physically ill and healthy people in both clinical and research contexts (7, 8, 10–13). Factors that interfere with sufficient consent in dementia (14, 15) and in affective and psychotic illnesses include cognitive deficits or information-related limitations (13, 16), neuropsychiatric symptoms (13, 17, 18), diminished communication between clinicians and mentally ill individuals in consent processes (19–21), and pressures that negatively affect voluntarism (19, 22, 23). Additional data also suggest that individuals with mental illness may not understand the difference between clinical research and clinical care and how specific protocol attributes such as use of random assignment, blinding, or control procedures may be important to their experiences in research (19, 24, 25). Some researchers have found that psychiatric symptoms may not in fact have as negative an impact upon decision making as once suspected (16, 26, 27), and data are mixed on the value of various interventions designed to improve consent processes (16, 28, 29). For these reasons, much remains to be understood about the abilities of individuals with schizophrenia who may become research participants.

Structured interview studies have emerged as one strategy for determining whether people who are eligible for research participation possess the capacity to discern critical aspects of varying protocols (15, 17, 26, 28, 30–32). In this method, hypothetical vignettes are presented, and participant responses to the situations are then examined. Limited but intriguing empirical work of this kind has been performed in individuals with schizophrenia and dementia and in the elderly. Stanley et al. (26, 28, 32, 33) performed a series of studies in which individuals with physical and mental disorders responded to hypothetical research projects with systematically varied risk-benefit ratios. This team found that psychiatric and medical patients did not differ on key aspects of research-related decision making (26, 32). On other measures, however, the presence of a psychiatric diagnosis significantly affected responses to the vignettes (28), and elderly and dementia patients had greater difficulty with information retention and comprehension than did comparison subjects (15, 17, 33). Similarly, Sachs et al. (30) presented four research vignettes to dementia patients, proxy decision makers, and well elderly individuals and found that the patients’ willingness to enroll decreased as the invasiveness of the studies increased. These data suggest that potential participants may be capable of discerning study attributes such as risks and benefits of specific procedures when confronted with hypothetical vignettes in structured interviews (30). Moreover, these results derived from vignette-based studies parallel findings obtained through studies employing other methods, including naturalistic observation (19) and attitude assessments of participants with mental illness (32).

To date, no vignette-based structured interview studies, to our knowledge, have investigated how people with schizophrenia assess research protocols that include a medication washout or a placebo treatment condition. Few data exist to help clarify how schizophrenia patients view these protocol designs in terms of potential harm, their willingness to participate, and potential influences on their participation decisions, such as physician or family preferences and monetary incentives. Finally, to our knowledge, no empirical work has been performed to explore how psychiatrists perceive these same considerations, nor do we have a sense of how well psychiatrists understand the views of people with schizophrenia.

To address this gap, we sought to examine the perspectives of schizophrenia patients and psychiatrists regarding two main experimental design elements—medication washouts and placebo treatment conditions. Our goal was to determine whether patients with schizophrenia would meaningfully distinguish between studies that involved or did not involve these characteristics. We also sought to determine the similarity of patients’ perceptions of these decisions and those of clinicians. We hypothesized that schizophrenia participants would 1) assess pharmacological treatment studies as more harmful than studies involving the drawing of a single blood sample; 2) assess protocols involving medication washouts or placebo treatment conditions as more harmful than identical protocols lacking these elements; 3) express less willingness to participate in protocols perceived as posing greater harm; 4) find these decisions difficult; 5) acknowledge the influence of family members and personal physicians upon their participation decisions; and 6) express greater willingness to participate in studies offering monetary incentives. For the psychiatrists, we hypothesized that 1) their personal views would generally mirror the views of the schizophrenia participants; 2) they would underestimate schizophrenia patients’ abilities to identify harm; and 3) they would overestimate schizophrenia patients’ assessments of decision difficulty, their willingness to participate in studies, and the impact of doctors and families on enrollment decisions.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Patients with a clinical diagnosis of schizophrenia from the University of New Mexico Mental Health Center, the New Mexico VA Health Care System, and Johns Hopkins University were invited to participate in this study, which received institutional review board approval. To mimic schizophrenia patient referrals to typical psychotic research studies, only those inpatients and outpatients assessed by their psychiatrists to be capable of decision making and sufficiently stable to tolerate a 2-hour videotaped interview were referred to our study. All study procedures were fully explained to patient participants before they signed a written consent form, approved by the institutional review board, prior to participating in the study. The patients’ most recent medical records were also reviewed to confirm their clinical DSM-IV diagnoses. Patient participants received $25.

All attending psychiatric faculty and resident psychiatrists at the University of New Mexico Mental Health Center and the New Mexico Veterans Health Care System were asked via mail to voluntarily complete a parallel written survey, but they were not required by the institutional review board to sign a separate written consent form. Their consent to participate was indicated by their decision to return the survey.

Instruments

Patients were interviewed to assess 1) background information, 2) general attitudes about biomedical research, 3) views about actual or hypothetical research participation, and 4) responses to vignettes describing hypothetical research protocols. Upon completion, each interview was evaluated on eight dimensions: level of participant comprehension, participant’s ability to focus, whether a rapport was established, participant comfort level, interviewer comfort level, whether hallucinations were apparent, whether delusional content was expressed, and the overall quality of the interview.

The four vignettes depicting hypothetical protocols are best understood as two pairs (Appendix 1). In the first pair of protocols, the study procedure involved taking a sample of blood from a person with schizophrenia to develop a diagnostic test for this illness (i.e., no expected therapeutic or other benefit to the individual participant). The difference between vignette 1 (relatively lower risk) and vignette 2 (relatively higher risk) was the introduction of a “several-day” medication washout period before the collection of the blood sample in vignette 2. In the second protocol pair, a new, potentially beneficial medication with the side effect of nausea was tested. The difference between vignette 3 (relatively lower risk) and vignette 4 (relatively higher risk) was the introduction in vignette 4 of three blind, randomly assigned conditions: the new medicine, another conventional medicine, or placebo. We chose to include a vignette that had ecological validity by including both random assignment and a placebo condition.

In a written survey, psychiatrists indicated their personal attitudes on the same questions asked of patients, and also predicted responses of “schizophrenia patients in general.” Psychiatrists were used as the comparison group in this study for three reasons: 1) they have direct responsibility for and understanding of psychiatric research protocols; 2) they work closely with people who have serious mental illnesses and have knowledge of the clinical characteristics and suffering associated with these disorders; and 3) no systematic data on the perspectives of psychiatrists have been gathered despite the centrality of research ethics issues to their professional work.

Dependent Variables

Participants were asked for each hypothetical protocol to rate the harmfulness of the protocol, the likelihood that they would participate in that protocol, and their difficulty in deciding whether to participate. They were also asked about the likely influence of being offered money to participate, their doctor asking them to participate, and their family asking them to participate. Participants indicated in open-ended responses the reasons why they would or would not participate in each protocol. To partially validate the ratings of protocol harm and willingness to participate, we correlated composite ratings from the four protocols with three scales that measure general attitudes about research (assessed in another study [25]): motivations to participate in research, autonomy of decisions to participate, and acceptability of participation in research by vulnerable populations. All three attitude dimensions were correlated with perceptions of protocol harm (mean r=0.38, df=127, p<0.01) and willingness to participate (mean r=0.40, df=127, p<0.01). In addition, the three influence measures were correlated with the general attitudes about research (mean r=0.33, df=127, p<0.02).

Independent Variables

Both protocol type and relative risk were repeated measures factors, and respondent (patient versus psychiatrist) was a between-subjects factor. Patient responses were compared in separate multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVAs) to the personal responses of psychiatrists and to their predictions for patients. The first three ratings (harmfulness, participation likelihood, and decision difficulty) were analyzed in three separate MANOVAs. The last three ratings were analyzed as an additional repeated measures factor, influence source (money versus doctor versus family), in a fourth set of analyses.

Results

Characteristics of Respondents

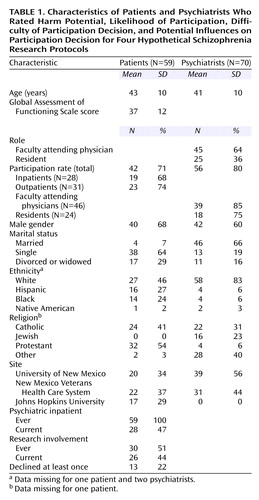

Eighty-four people with clinical diagnoses of schizophrenia were invited, and 63 (75%) chose to participate in the study. Fifty-nine of the 63 provided complete responses to all vignettes (Table 1). All had been psychiatric inpatients (median admissions=6), and 47% were hospitalized during this study. Medical record documents confirmed the schizophrenia diagnosis and revealed that all were currently receiving some psychotropic medication (antipsychotic: 92% [N=54]; side effect medication: 44% [N=26]; benzodiazepine: 37% [N=22]; antidepressant: 25% [N=15]; another mood stabilizer: 12% [N=7]). Their most recent Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores ranged from 20 to 70 (mean=37, median=35, SD=12). In rating their own mental health problems in the preceding 3 months on a 5-point scale (1=none, 5=a lot), roughly one-fifth rated each point (mean=3.20, SD=1.44). Specific problems reported by most of the patients in the preceding 3 months (rated on a 5-point scale in which 1=never and 5=all the time) were hearing voices (68%, N=40; mean=2.78 [SD=1.57]) and feeling frightened (80%, N=47; mean=2.90 [SD=1.40]). Only 68% (N=40) reported believing that they actually had schizophrenia, although 95% (N=56) said that they had been told this diagnosis by a doctor. Patient reports of hearing voices, experiencing fear, and experiencing problems with mental health over the past 3 months were intercorrelated (mean r=0.36, df=116, p<0.01). No patient characteristics (e.g., score on Global Assessment of Functioning Scale, symptoms, medication) moderated their ratings of the protocols.

Eighty-eight faculty and resident psychiatrists were invited, and 73 (83%) completed written surveys. Of these, 70 (96%) provided complete responses to all vignettes (Table 1). No psychiatrist characteristics (e.g., gender, age, practice site) moderated their ratings of the protocols.

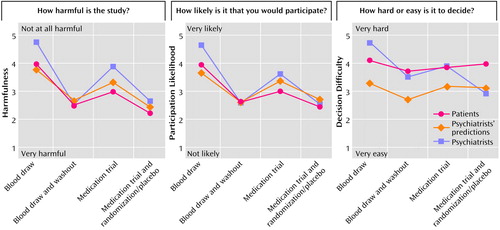

Perceptions of Harmfulness

In support of our hypotheses, schizophrenia patients and psychiatrists both perceived large and substantially different levels of harm across the vignettes. As seen in Table 2 and Figure 1, the pattern of the means across the four protocols was similar for both patients and psychiatrists, although overall psychiatrists personally perceived the protocols as less harmful than did patients (Table 3, main effect for respondent). Significantly greater harm was assigned to the medication trials than the blood draw studies (Table 3, main effect for protocol type) and to the protocols involving washout and placebo features in comparison with parallel studies without these features (Table 3, main effect for relative risk). These three main effects were qualified by two significant interactions. First, whereas only a small difference existed between patients and psychiatrists in perceptions of harm for higher-risk studies (i.e., those with medication washouts and placebo treatment conditions), patients saw the analogous lower-risk studies as much more harmful than did the psychiatrists (Table 3, interaction effect for respondent and relative risk). Second, both groups of respondents saw a much greater difference in harm when adding a higher-risk condition to the blood draw study (d=1.82) than to the medication trial (d=1.00) (Table 3, interaction effect for relative risk-by-protocol type).

Psychiatrists’ predictions of patient ratings of protocol harmfulness were generally accurate (Table 2). As hypothesized, however, patients perceived greater harmfulness in the medication trials than was predicted by psychiatrists.

Likelihood of Participation

Overall, psychiatrists were more likely than patients to participate (Table 3, main effect for respondent). Both patients and psychiatrists indicated that they would be more likely to participate in the lower-risk studies in which a medication washout or a placebo condition was absent (Table 3, main effect for relative risk), and all were more likely to participate in the blood draw protocols than the medication trials (Table 3, main effect for protocol type). Across the four protocols, the mean correlation for patients between perceptions of harmfulness and participation likelihood was, as expected, large (mean r=0.57, df=116, p<0.001). Psychiatrists were more likely than patients to participate in the studies in which a medication washout or placebo condition was absent (Table 3, interaction effect for respondent and relative risk). No difference existed between respondent groups for higher-risk studies with those features. Both groups of respondents saw a much greater difference in harm when adding a higher-risk condition to the blood draw study (d=1.58) than to the medication trial (d=0.80) (Table 3, interaction effect for relative risk-by-protocol type).

Psychiatrists’ predictions for schizophrenia patients were generally accurate. However, the psychiatrists overestimated patients’ likelihood of participating in the medication trials but underestimated their reported likelihood of participating in the blood draw protocols (Table 3, interaction effect for respondent and protocol type).

Difficulty of Participation Decision

Overall, both patients and psychiatrists indicated that participation decisions were not hard, but decisions for lower-risk studies (Table 3, main effect for relative risk) and for blood draw studies (Table 3, main effect for protocol type) were rated by both groups as easier than decisions for higher-risk studies and medication trials, respectively. No correlation was found between perceived difficulty in making an enrollment decision and assessments of harm (mean r=0.05) or responses on the likelihood of participating (mean r=0.15). Two interesting interactions were noted. First, psychiatrists found it easier than patients to decide about lower-risk studies (d=0.28), whereas patients found it easier than doctors to decide about higher-risk studies (d=–0.50) (Table 3, interaction effect for respondent and relative risk). Second, psychiatrists found it easier than patients to decide about blood draw studies (d=0.17), whereas patients found it easier than doctors to decide about medication trials (d=–0.30) (Table 3, interaction effect for respondent and protocol type).

Overall, patients reported that it was much easier to decide about the four protocols than predicted by the psychiatrists (Table 3, main effect for respondent).

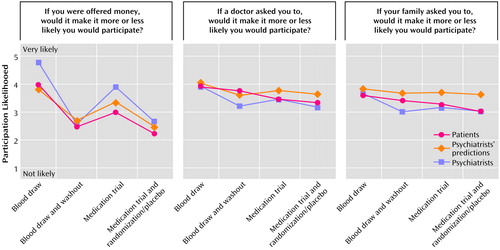

Source of Influence

Schizophrenia patients and psychiatrists acknowledged that the three sources of influence (money, doctor, and family) would slightly increase their likelihood of participation in the protocols (Table 3, main effect for influence source). In particular, both groups reported more likelihood of being influenced by monetary incentives or by their doctors than by their families (Figure 2). It is important to note that for higher-risk studies relative to those of lower risk, both groups reported being less likely to be influenced by any source (Table 3, main effect for relative risk). Both groups also reported that participation in medication trials, as opposed to blood draw studies, was less likely to be influenced by any source (Table 3, main effect for protocol type). Likelihood of participation was consistently correlated with each measure of potential influence, with doctor’s influence being the most strongly correlated with participation likelihood (doctor’s influence: mean r=0.44, df=57, p<0.02; family influence: mean r=0.35, df=57, p<0.02; monetary incentives: mean r=0.30, df=57, p<0.02).

Overall, psychiatrists predicted that the three sources (money, doctor, and family) would have more influence on the participation decision of schizophrenia patients than the patients rated themselves (Table 3, main effect for respondent). Psychiatrists were more accurate in predicting patient influences for participation in blood draw studies than they were in predicting influences for medication trial participation (Table 3, interaction effect for respondent and protocol type). Psychiatrists were also more accurate in predicting the degree of potential influence that patients would attribute to their personal doctor’s recommendations than they were in predicting the influence patients would attribute to monetary inducements and family member requests (Table 3, interaction effect for relative risk, influence source, and respondent).

Moderating Variables

Site differences were not found in the responses of schizophrenia patients or psychiatrists. Psychiatrist characteristics did not reliably predict or moderate their responses. With respect to patient characteristics, to explore the potential impact of disorder severity and symptoms on the vignette ratings, we used a recent clinician rating of the patient’s level of general adaptive functioning as a design variable by splitting at the median (Global Assessment of Functioning Scale score=35). Results showed no effects for variations in Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores on vignette ratings by patients (all p>0.29), although Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores were correlated with outpatient versus inpatient status (r=0.43, df=57, p<0.01). A composite variable from three measures of patient self-reported recent psychiatric symptoms (mean r=0.36, df=57, p<0.01) showed no effects for variations in the responses (all p>0.55). A composite variable based on the schizophrenia patient’s level of functioning during the interview revealed no effects; i.e., regardless of their level of functioning during the interview, schizophrenia patients reliably discriminated between the types of protocols and the relative risk of those studies in patterns described in the main analyses.

Independent analyses of the patient responses that used the protocol type-by-relative risk design but added a third factor of patient status (inpatient versus outpatient) did produce some significant effects. Ratings of harmfulness responded much more to variations in the relative risk for outpatients (d=1.11) than for inpatients (d=0.53) (F=4.76, df=2, 55, p<0.04). Ratings of harmfulness were also more responsive to variation in protocol type (i.e., blood draw versus medication trial) for outpatients (d=0.59) than for inpatients (d=0.12) (F=4.27, df=2, 55, p<0.05). Ratings of participation likelihood followed the same pattern (variations in relative risk: F=9.90, df=1, 55, p<0.01; variations in protocol type: F=4.02, df=2, 55, p<0.05). In summary, in comparison with inpatients, the outpatients saw studies without medication washouts or placebo conditions as less harmful and expressed greater likelihood of participating in these studies. Ratings of decision difficulty also followed the same outpatient versus inpatient pattern (variations in relative risk: F=4.33, df=1, 55, p<0.05; variations in protocol type: F=11.22, df=1, 55, p=0.001). Analyses of potential sources of influence on patients’ participation decisions showed that family requests were less of an influence for outpatients than for inpatients (F=3.19, df=2, 55, p<0.05; d=0.28) and that a doctor’s recommendation was more influential for outpatients than for inpatients (F=3.19, df=2, 55, p<0.05; d=0.28). No differences were detected between inpatients and outpatients for the perceived influence of money on their decisions to participate.

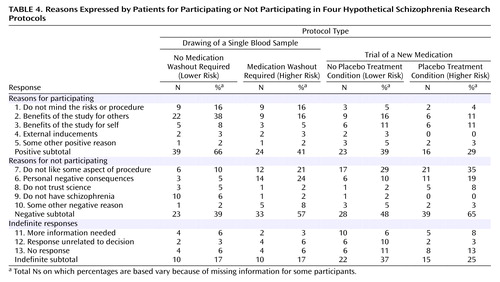

Narrative Responses

Patient participants provided open-ended responses to the question, “Why would you or would you not participate in this research study?” for each vignette. Two authors (L.W.R. and J.L.B.) independently reviewed the responses to produce 12 categories (Table 4). After three authors (L.W.R., T.D.W., and J.L.B.) discussed the coding categories, two authors (L.W.R. and J.L.B.) separately coded participants’ verbal responses for each of the four protocol vignettes, with a consensus code used for any instances of disagreement. These original codes produced kappa coefficients of intercoder agreement of 0.74, 0.86, 0.90, and 0.96 for the respective vignettes (all p<0.0001). Analyses of the qualitative responses are based only upon the consensus codes. Consistent with the harm and participation willingness ratings, Table 4 shows a general linear trend in which the frequency of reasons for participating decreases across the protocols (χ2=8.92, df=3, p<0.01) and the frequency of reasons for not participating increases (χ2=6.22, df=3, p<0.03).

Discussion

This study contributes to the current discussion of ethical aspects of schizophrenia research by characterizing the assessments made by schizophrenia patients and psychiatrists of hypothetical protocols and their related participation decisions. We focused specifically on the impact of two scientific design elements that pose greater risk for participants and are the subjects of considerable controversy: medication washout periods and placebo treatment conditions. Our study further offers novel data about psychiatrists’ personal views and their predictions of schizophrenia patient ratings. On the basis of these data we may begin to answer some of the pivotal questions raised when considering the ethics of schizophrenia research. Are patients with serious mental illnesses such as schizophrenia capable of meaningfully interpreting scientific design features? How might factors such as monetary incentives and doctor and family recommendations affect participation decisions, according to prospective recruits? How do psychiatrists view these issues, and how accurate are they in predicting the perspectives expressed by schizophrenia patients?

Capacity to Assess Varying Scientific Design Features

The schizophrenia patients in this preliminary study were able to discern key aspects of the hypothetical protocols presented in the structured interviews. First, they assigned substantially different levels of harm across the vignettes, and their assessments resembled those of psychiatrists. The protocols with medication washouts and placebo treatment conditions were seen as relatively more harmful than studies without these features, and the medication trials were seen as more harmful than studies involving the drawing of a blood sample. Second, like the psychiatrists in our study, the patients with schizophrenia expressed greater reluctance to participate in projects that, in their eyes, posed greater potential harm. Third, the narrative comments proffered by the schizophrenia patients reflected attentiveness to protocol features. Moreover, these features appeared to shape the patients’ reasons for or against participation (e.g., specific interventions and procedures, benefits to self or others, negative personal consequences). It is interesting to note that the schizophrenia patients reported that these decisions were relatively easy for them to make—a finding that psychiatrists had not accurately predicted.

While very important in the current national debate regarding the capacity of schizophrenia patients to understand and fully appreciate the meaning of specific scientific designs, these results should be interpreted in light of three issues. The first consideration is our patient group. Our schizophrenia participants were judged to be capable of decision making by their clinicians. They were nevertheless severely ill. All had been inpatients in the past, and half were voluntarily hospitalized at the time of the study. The majority had reported hearing voices and feeling frightened recently; a large minority questioned their schizophrenia diagnosis, and their Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores were relatively poor. In addition, half had direct experience as protocol participants, and many had declined research participation in the past. These qualities suggest that our findings are not attributable to having only the healthiest of schizophrenia participants in our study, nor are they due to having recruited only protocol “accepters.” Second, the inpatient participants (all of whom were voluntarily hospitalized) demonstrated less sensitivity to design features in their responses than did the outpatients. Other intriguing differences between responses of inpatients and outpatients were also found. For example, participation willingness and the role of family members and of doctors in enrollment decisions differed according to inpatient versus outpatient status. How these findings relate to aspects of the patients’ illnesses, life situation, and clinical context merit further study. Finally, a similar pattern emerged when comparing responses of patients as a group to those of psychiatrists. Psychiatrists discriminated more than patients between the various protocols (i.e., wider range of means) on every measure, but psychiatrists’ responses to individual vignettes were more uniform than were those of the schizophrenia patients (i.e., smaller standard deviations). Thus, compared with patients, psychiatrists agreed more in their responses to the protocols and also distinguished more between the types of studies. Whether this reflects less ability of the patients as a group to understand the protocols or some other factor cannot be determined from these data.

In sum, as hypothesized, it appears that at least a subset of people with schizophrenia are able to express meaningful participation decisions related to hypothetical protocols with variable designs. While we do not yet fully understand the factors affecting the actual protocol enrollment choices made by mentally ill individuals, our data suggest the importance of gaining greater knowledge of the true strengths and specific capacities of people with schizophrenia who may be recruited as research participants.

Influences Upon Participation Decisions

The impact of monetary incentives and the appropriate roles of doctors and family members in mental illness research are controversial issues that have previously received little empirical study. It is important to note that all three of these external influences upon participant decision making were perceived as less influential as studies became more harmful in the eyes of the participants. Our respondents indicated that money is a clear inducement to research participation, although perhaps not as powerful a force as many, including psychiatrists, believe. A doctor’s recommendation in support of participation was a positive influence with similar valence as a monetary incentive, but again, this was not as strong an influence as might be predicted on the basis of early work on the “therapeutic misconception.” It is of interest that a family member’s support of participation was perceived as a relatively less potent factor in enrollment decisions. Because family members serve as important advocates and alternative decision makers for some mentally ill people, these findings warrant our attention and additional study across diverse psychiatric research sites.

The potential for coercion during research recruitment and consent processes is a very compelling ethical consideration in schizophrenia research (8, 10). Our data suggest that, in a formal but nonpressured hypothetical decision-making context, some schizophrenia patients are capable of expressing logical decisions and of indicating clear personal reasons behind their choices. They are also capable of stating the degree to which they would feel influenced by financial inducement or the opinions of others. Much remains to be understood about the true effects of complex pressures and influences upon actual participation choices.

Perspectives and Predictions of Psychiatrists

Psychiatrists’ personal perspectives and their attunement to the views of patients with schizophrenia are important because these professionals are entrusted with the dual responsibility of treating and researching serious mental illnesses. Our results suggest that psychiatrists see greater harm associated with studies that entail medication washouts or random assignment to a placebo treatment condition. The psychiatrists in this study also had a reasonably accurate sense of patient perspectives on many measures, particularly for ratings of perceived harm and participation willingness. Nevertheless, the psychiatrists indicated that patients would see the medication trials as less harmful than patients actually did. Psychiatrists overestimated patients’ reported likelihood of participating in the medication trials, while they underestimated their willingness to participate in blood draw protocols. And, just as we did, psychiatrists greatly overestimated the difficulty of making protocol decisions as reported by the schizophrenia patients. Finally, psychiatrists overestimated the influence of physicians, families, and incentives in enrollment decisions as reported by the patients. Thus, our hypotheses regarding psychiatrists’ predictions of patient responses were partially confirmed.

The differences across psychiatrists’ personal views, their predictions of patient ratings, and patients’ actual reports have several interpretations and raise many new empirical questions. For instance, our schizophrenia participants did not endorse the strong level of influence predicted by psychiatrists for monetary incentives and doctor and family requests. Is this because people with schizophrenia are unaware of, or unwilling to acknowledge, the real contribution of these factors? Or, alternatively, is it that psychiatrists do not fully appreciate the manner by which schizophrenia patients actually arrive at protocol participation decisions? Moreover, psychiatrists’ personal views and patient views differed significantly on certain measures for three of the four vignettes. How might this discrepancy affect their referral, recruitment, and consent practices of psychiatrists for protocols of varying properties? As with our previous work reporting general attitudes of schizophrenia patients and psychiatrists toward research (25), we conclude that these findings suggest the importance of more deeply exploring the perspectives of all who are intimately involved with mental illness research.

Limitations

This study provides empirical evidence concerning issues that are pressing clinical, scientific, and policy discussions at this time. The data echo the findings of analogous patient studies that employed a structured interview and self-report design but which did not prospectively measure actual decisions or behaviors (15, 18, 26, 30). As reported previously (25), we assessed the views of people with a clinical diagnosis of schizophrenia who were viewed as capable of decision making and who would thus be considered potential candidates for research participation. Accordingly, our selection and recruitment processes were constructed to resemble those of clinical research protocols at three sites with varying levels of involvement in clinical investigation. This ecologically oriented approach involved confirmation of the diagnosis by clinical chart review, although it did not include a formal diagnostic interview. The fact that 25% of the patients we approached declined to participate suggests that our recruitment process was noncoercive, but this fact must also be considered in judging the extent of generalizability of our findings. Concerns about representativeness of the patient data may be addressed partly by the absence of site differences. The attending and resident psychiatrists in our group from the New Mexico sites were assessed only through a written self-report instrument. No differences were predicted or found among the two sites. Although we obtained a high response rate, a broader sample of psychiatrists from more sites would increase confidence in the generalizability of findings to other clinicians.

Conclusions

The people with schizophrenia in our study made meaningful, discerning harm assessments and participation decisions as explored through hypothetical protocols with variable design elements. These individuals expressed less willingness to participate in studies seen as posing greater potential risk. They assigned only mild influence to monetary incentives, doctor’s recommendations, and family preferences—findings that may allay some concerns while stimulating others regarding the potential for exploitation of mentally ill research participants. Psychiatrists’ personal views, their predictions of schizophrenia patient views, and the perspectives actually expressed by these seriously mentally ill individuals revealed interesting similarities and differences. These varying responses suggest the importance of exploring these issues in interactions with our patients and our colleagues. Systematic empirical research and educational efforts on the ethical aspects of schizophrenia research remain critically important. These data indicate the potential fruitfulness of further inquiry into the abilities and perspectives of individuals with serious mental illness, as invited by the first principle of research ethics, Respect for Persons.

|

|

|

|

Received May 1, 2001; revision received Nov. 14, 2001; accepted Dec. 6, 2001. From the Empirical Ethics Group, University of New Mexico School of Medicine; the New Mexico VA Health Care System, Albuquerque; and Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. Address reprint requests to Dr. Laura Roberts, Department of Psychiatry, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, 2400 Tucker, N.E., Albuquerque, NM 87131-5326; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by a Young Investigator Award from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression. Dr. Laura Roberts is supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH-01918). Dr. Brian Roberts is supported by the New Mexico VA Health Care System. The authors thank Samuel J. Keith, M.D., Jose Canive, M.D., Melinda Rogers, Russell Horwitz, Megan Smithpeter, Gregory Sachs, M.D., Graham Redgrave, M.D., Thomas Dimatteo, M.D., and Kate Canfield, M.D., for their contributions to the development and completion of this project.

|

APPENDIX 1.

Figure 1. Patient (N=59) and Psychiatrist (N=70) Ratings and Psychiatrists’ Predictions of Patient Ratings for Four Hypothetical Schizophrenia Research Protocols in Terms of Harm Potential, Likelihood of Participation, and Difficulty of Participation Decision

Figure 2. Patient (N=59) and Psychiatrist (N=70) Ratings and Psychiatrists’ Predictions of Patient Ratings for Four Hypothetical Schizophrenia Research Protocols in Terms of Potential Influences on the Participation Decision

1. Michels R: Are research ethics bad for our mental health? N Engl J Med 1999; 340:1427-1430Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. National Bioethics Advisory Commission: Research Involving Subjects With Mental Disorders That May Affect Decisionmaking Capacity: Report and Recommendations of the National Bioethics Advisory Commission. Washington, DC, National Bioethics Advisory Commission, 1998Google Scholar

3. Appelbaum PS: Drug-free research in schizophrenia: an overview of the controversy. IRB: A Review of Human Subjects Research 1996; 18:1-5Google Scholar

4. Department of Health and Human Services Statement by Steven E Hyman on Fiscal Year 1999 President’s Budget Request for the National Institute of Mental Health. Washington, DC, National Institute of Mental Health, 1999, p 4Google Scholar

5. Shamoo A: Ethics in Neurobiological Research with Human Subjects. Amsterdam, Gordon & Breach, 1997Google Scholar

6. National Alliance for the Mentally Ill: Ethical issues raised by study design, in IRB Training Guide. http://www.nami.org/research/chapter4.htmlGoogle Scholar

7. Roberts L: The ethical basis of psychiatric research: conceptual issues and empirical findings. Compr Psychiatry 1998; 39:99-110Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Roberts L, Roberts B: Psychiatric research ethics: an overview of evolving guidelines and current ethical dilemmas in the study of mental illness. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 46:1025-1038Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Sugarman J, McCrory DC, Powell D, Krasny A, Adams B, Ball E, Cassell C: Empirical research on informed consent: an annotated bibliography. Hastings Cent Rep 1999; 29:S1-S42Google Scholar

10. Appelbaum PS, Mirkin SA, Bateman AL: Empirical assessment of competency to consent to psychiatric hospitalization. Am J Psychiatry 1981; 138:1170-1176Link, Google Scholar

11. Appelbaum PS, Grisso T: The MacArthur Competence Study, I: mental illness and competence to consent to treatment. Law Hum Behav 1995; 19:105-126Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS, Mulvey EP, Fletcher K: The MacArthur Competence Study, II: measures of abilities related to competence to consent to treatment. Law Hum Behav 1995; 19:127-148Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS: The MacArthur Treatment Competence Study, III: abilities of patients to consent to psychiatric and medical treatments. Law Hum Behav 1995; 19:149-174Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Agarwal M, Ferran J, Ost K, Wilson K: Ethics of “informed consent” in dementia research—the debate continues. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1996; 11:801-806Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Stanley B, Guido J, Stanley M, Shortell D: The elderly patient and informed consent: empirical findings. JAMA 1984; 252:1302-1306Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Carpenter WT Jr, Gold JM, Lahti AC, Queern CA, Conley RR, Bartko JJ, Kovnick J, Appelbaum PS: Decisional capacity for informed consent in schizophrenia research. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:533-538Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Stanley B, Stanley M, Guido J, Garvin L: The functional competency of elderly at risk. Gerontologist 1988; 28(June suppl):53-58Google Scholar

18. Schachter D, Kleinman I, Prendergast P, Remington G, Schertzer S: The effect of psychopathology on the ability of schizophrenic patients to give informed consent. J Nerv Ment Dis 1994; 182:360-362Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Lidz C: Informed Consent: A Study of Decisionmaking in Psychiatry. New York, Guilford, 1984Google Scholar

20. Benson P: Informed consent: drug information disclosed to patients prescribed antipsychotic medication. J Nerv Ment Dis 1984; 172:642-653Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Kaufmann C, Roth L: Psychiatric evaluation of patient decision-making: informed consent to ECT. Soc Psychiatry 1981; 16:11-19Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Du Mont J, Stermac L: Research with women who have been sexually assaulted: examining informed consent. Can J Hum Sexuality 1996; 5:185-191Google Scholar

23. Valimaki M, Leino-Kilpi H, Helenius H: Self-determination in clinical practice: the psychiatric patient’s point of view. Nurs Ethics 1996; 3:329-344Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Appelbaum P, Roth L, Lidz C: The therapeutic misconception: informed consent in psychiatric research. Int J Law Psychiatry 1982; 5:319-329Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Roberts LW, Warner TD, Brody JL: Perspectives of patients with schizophrenia and psychiatrists regarding ethically important aspects of research participation. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:67-74Link, Google Scholar

26. Stanley B, Stanley M, Lautin A, Kane J, Schwartz N: Preliminary findings on psychiatric patients as research participants: a population at risk? Am J Psychiatry 1981; 138:669-671Link, Google Scholar

27. Soskis DA: Schizophrenic and medical inpatients as informed drug consumers. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35:645-647Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Stanley B, Stanley M, Stein J, Guido L, Transit RP: Psychopharmacologic treatment and informed consent: empirical research. Psychopharmacol Bull 1985; 21:110-113Medline, Google Scholar

29. Benson PR, Roth LH, Appelbaum PS, Lidz CW, Winslade WJ: Information disclosure, subject understanding, and informed consent in psychiatric research. Law Hum Behav 1988; 12:455-475Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Sachs GA, Stocking CB, Stern R, Cox DM, Hougham G, Sachs RS: Ethical aspects of dementia research: informed consent and proxy consent. Clin Res 1994; 42:403-412Medline, Google Scholar

31. Gallo C, Perrone F, De Placido S, Giusti C: Informed versus randomised consent to clinical trials. Lancet 1995; 346:1060-1064Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Stanley B, Stanley M: Psychiatric patients’ comprehension of consent information. Psychopharmacol Bull 1987; 23:375-378Medline, Google Scholar

33. Stanley B, Stanley M: Competency and informed consent in geriatric psychiatry, in Geriatric Psychiatry and the Law: Critical Issues in American Psychiatry and the Law, vol 3. Edited by Rosner R, Schwartz HI. New York, Plenum, 1987, pp 17-28Google Scholar