Gender Differences in Treatment Response to Sertraline Versus Imipramine in Chronic Depression

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors examined gender differences in treatment response to sertraline, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), and to imipramine, a tricyclic antidepressant, in chronic depression. METHOD: A total of 235 male and 400 female outpatients with DSM-III-R chronic major depression or double depression (i.e., major depression superimposed on dysthymia) were randomly assigned to 12 weeks of double-blind treatment with sertraline or with imipramine after placebo washout. RESULTS: Women were significantly more likely to show a favorable response to sertraline than to imipramine, and men were significantly more likely to show a favorable response to imipramine than to sertraline. Gender and type of medication were also significantly related to dropout rates; women who were taking imipramine and men who were taking sertraline were more likely to withdraw from the study. Gender differences in time to response were seen with imipramine, with women responding significantly more slowly than men. Comparison of treatment response rates by menopausal status showed that premenopausal women responded significantly better to sertraline than to imipramine and that postmenopausal women had similar rates of response to the two medications. CONCLUSIONS: Men and women with chronic depression show differential responsivity to and tolerability of SSRIs and tricyclic antidepressants. The differing response rates between the drug classes in women was observed primarily in premenopausal women. Thus, female sex hormones may enhance response to SSRIs or inhibit response to tricyclics. Both gender and menopausal status should be considered when choosing an appropriate antidepressant for a depressed patient.

Although the gender difference in the prevalence of unipolar depression has been well established (1–3), little attention has been paid to gender differences in treatment response to antidepressant medications. Possible sex differences in response to imipramine were first noted several decades ago (4, 5). In a recent meta-analysis of 35 studies published between 1957 and 1991 that reported imipramine response rates separately by gender, men responded more favorably to imipramine than did women (6). A study comparing tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) found that in patients with atypical depression and associated panic attacks, women showed a more favorable response to MAOIs and men to tricyclic antidepressants (7). These differential response patterns suggest that gender should be considered when making treatment decisions.

However, to our knowledge, no published studies have examined gender differences in response to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), currently the most widely used class of antidepressants. In addition, we could find no studies of gender differences in treatment response among chronically depressed patients. Chronic depressive disorders have received increasing attention in recent years because of their underdiagnosis and undertreatment and the morbidity and costs associated with these disorders (8, 9). We previously reported gender differences in the presentation of chronic depression in a large clinical sample of men and women with DSM-III-R chronic major depression or double depression (major depression superimposed on dysthymia) (10, 11). In this article, we examine gender-specific differences in treatment response to sertraline, a newer SSRI, and to imipramine, a representative tricyclic antidepressant, in this same clinical cohort.

Method

Subjects were 235 men and 400 women who participated in a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group comparative trial of sertraline and imipramine in the treatment of chronic major depression and double depression. The study rationale, design, methods, and inclusion/exclusion criteria have been detailed in manuscripts by Rush et al. (12) and Keller et al. (13). Individuals age 21–65 years who met DSM-III-R criteria for chronic major depression (i.e., major depression of at least 2 years’ duration without antecedent dysthymia) or double depression (i.e., major depression superimposed on dysthymia) were recruited through advertisement or medical referral to one of 10 university-affiliated medical centers or two clinical research centers. After a complete description of the study was given to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained.

A 24-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (14) score of ≥18 and a Clinical Global Impression (CGI) (15) severity scale score of ≥3 after 1 week of placebo washout were required for study entry. Subjects were randomly assigned to 12 weeks of double-blind treatment with sertraline or imipramine in a 2:1 ratio. (The 2:1 ratio was used because of a second random assignment of patients who received sertraline during the maintenance phase of the study, which is not described here.) The starting dose of both medications was 50 mg/day. The dose of imipramine was titrated by 50 mg/day each week, according to clinical response and the absence of dose-limiting side effects, to a maximum of 300 mg/day. Because sertraline is effective for some patients at the starting dose, the first opportunity to titrate the medication was at the end of week 3, at which point the dose could be increased by 50 mg/day per week to a maximum of 200 mg/day. The mean sertraline dose at endpoint was 139.6 mg/day (SD=59.7) in women and 143.2 mg/day (SD=58.8) in men. The mean imipramine dose at endpoint was 196.3 mg/day (SD=81.6) for women and 207.5 mg/day (SD=83.2) for men. The endpoint for each subject was defined as the last study visit attended, with the last observation carried forward.

Patient visits were scheduled at weekly intervals after initiation of medication for the first 6 weeks and biweekly thereafter. At each visit, the following rating scales were administered: the 24-item Hamilton depression scale, the CGI severity and improvement scales, and the Beck Depression Inventory (16). Adverse events, either reported by the patient or observed by the clinician, were recorded at each visit. Medication compliance was determined by pill counts.

Satisfactory therapeutic response was defined as a 50% decrease in the Hamilton depression scale score, a Hamilton depression scale score ≤15, a CGI severity scale score ≤3, and a CGI improvement scale score of 1 or 2 (corresponding to “very much” or “much improved”).

We focused on two primary research questions: Do the genders differ in their response to sertraline versus imipramine in terms of 1) response rate at study endpoint or 2) dropout rate? Evaluations of other parameters and subgroups were of secondary interest and were performed to help describe and support the main results. To control for type I error in multiple comparisons, the Bonferroni correction was applied. The p values from the two primary tests of interaction were evaluated for significance relative to p<0.05¸ 2=0.025. Unadjusted significance levels of p<0.05 were applied to all supportive and descriptive evaluations.

Men and women were compared for baseline characteristics by using Mantel-Haenszel chi-square tests for categorical variables and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables. All analyses adjusted for treatment group (sertraline or imipramine), depression type, and investigator site.

Gender and treatment groups were compared at endpoint for attrition and response rates by using Mantel-Haenszel chi-square tests, as just described. The pair-wise interactions between gender, treatment, and depression type were evaluated for statistical significance by using a logistic regression model that adjusted for investigator site. Changes from baseline to endpoint in continuous variables (e.g., Hamilton depression scale scores) were examined by using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with effects for baseline score, treatment group, gender, depression type, and investigator site. Interactions between gender, treatment, and depression type were also evaluated for inclusion in the model. Median time to discontinuation and time to response were estimated by using Kaplan-Meier survival methods. Patient groups were compared by using an unadjusted log rank test. The interactions between gender, treatment, and depression type were evaluated by using a Cox proportional hazards regression model that adjusted for investigator site.

The frequency of treatment-emergent adverse events in men and women was compared by using chi-square tests with Yates’s correction, or Fisher’s exact test for small samples. Treatment-emergent adverse events were those that either began or increased in severity after initiation of treatment.

Subgroups defined by characteristics other than gender (e.g., pre- versus postmenopausal women) were evaluated by using similar methods. Actual sample sizes varied slightly by parameter. All tests used two-tailed probability values.

Results

Differences at Baseline

Comparisons by gender at baseline have been presented and discussed in detail in a separate article (11). The findings are summarized in Table 1. Briefly, women were significantly younger than men. Men were significantly more likely to be married and to have a college degree, yet they were more likely to be unemployed (i.e., not employed outside the home, retired, or a student). Men and women were not significantly different in race.

Compared with men, women had significantly higher baseline severity ratings on the Hamilton depression scale, the CGI severity scale, and the Beck Depression Inventory. Women were significantly younger than men at the onset of their major depressive disorder. Men were significantly more likely to have dysthymia in addition to major depressive disorder. Women were significantly more likely to have received previous treatment for depression, including pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy, and to report a family history of affective disorder.

Dropout Rates

As Table 2 shows, a statistically significant interaction of gender and treatment was found for dropout rates. Women who were taking imipramine and men who were taking sertraline were more likely to withdraw from the study. Women who were taking imipramine were significantly more likely to drop out than women who were taking sertraline; 36 (26%) of 136 women randomly assigned to receive imipramine withdrew from the study, compared to 37 (14%) of 264 women randomly assigned to receive sertraline. In contrast, the dropout rates for men were 14 (19%) of 73 who took imipramine and 39 (24%) of 162 who took sertraline; this difference was not statistically significant (Mantel-Haenszel χ2=0.78, df=1, p=0.38). Analyses of time to discontinuation from the study showed similar results. The most common reason for dropout was adverse events, which accounted for nearly half of the patients who withdrew from the study.

Treatment Response

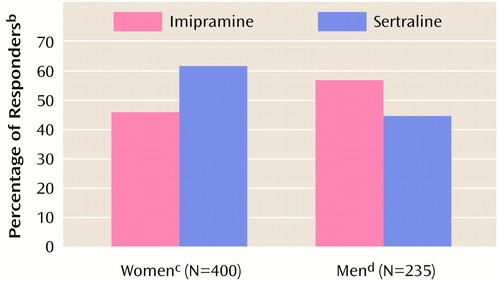

Response analysis using an intent-to-treat approach showed a statistically significant interaction of gender and treatment, with the highest response rates at endpoint (last study visit) seen in women who took sertraline and men who took imipramine (Figure 1). Women were significantly more likely to respond to sertraline than to imipramine (147 [57%] of 260 versus 61 [46%] of 133), and men were significantly more likely to respond to imipramine than to sertraline (43 [62%] of 69 versus 73 [45%] of 161). A response analysis of subjects who completed the 12-week trial also showed a statistically significant interaction of gender and treatment (Wald χ2=4.82, df=1, p=0.03), with women more likely to respond to sertraline than to imipramine and men more likely to respond to imipramine than to sertraline.

There was also a statistically significant interaction of gender and treatment for time to response (Cox proportional hazards regression model, χ2=7.56, df=1, p=0.006). Men responded significantly more rapidly than women to imipramine, with a median time to response of 8 weeks in men compared to 10 weeks in women (log rank χ2=4.17, df=1, p=0.04). Women tended to respond more rapidly than men to sertraline (10 versus 12 weeks median time to response), although this difference was not significant (log rank χ2=2.60, df=1, p=0.11).

Analyses based on scores on the Hamilton depression scale, CGI, and Beck Depression Inventory showed similar results, with women tending to respond better to sertraline and men to imipramine (Table 3). There was a statistically significant interaction of gender and treatment for the change in Hamilton depression scale score from baseline to endpoint, as well as for the changes in CGI severity scale score and Beck Depression Inventory score. The interaction of gender and treatment for the CGI improvement scale score at endpoint approached, but did not reach, statistical significance.

Adverse Events

Men and women taking either sertraline or imipramine showed no significant gender differences in overall frequency of treatment-emergent adverse events or in reports of severe adverse events (Table 4). However, women who were taking imipramine were significantly more likely to withdraw from the study because of adverse events than women who were taking sertraline (18 [13%] of 136 versus 17 [6%] of 264; Mantel-Haenszel χ2=5.20, df=1, p=0.02). Discontinuation rates due to adverse events for men who took imipramine and sertraline were 7 (10%) of 73 and 10 (6%) of 162, respectively; this difference was not significant (Mantel-Haenszel χ2=0.83, df=1, p=0.36).

As shown in Table 4, there were several statistically significant gender differences in types of adverse events with frequencies of occurrence of ≥10% in men or women. Among those taking sertraline, women were significantly more likely to report nausea and dizziness, and men were significantly more likely to report dyspepsia, sexual dysfunction, and urinary frequency. Among those taking imipramine, women were significantly more likely than men to report nausea and were more likely, but not significantly so, to report constipation and nervousness. Men taking imipramine were significantly more likely than women to complain of urinary frequency and sexual dysfunction. In addition, men taking imipramine were more likely to complain of other urinary disorders, but the gender difference was not significant.

Effect of Menopausal Status

Of the 400 women in the study, 301 (203 taking sertraline and 98 taking imipramine) were premenopausal and 74 (49 taking sertraline and 25 taking imipramine) were postmenopausal; for the remaining 25 women, menopausal status either could not be determined or the data were missing.

A significant interaction was found between treatment and menopausal status for dropout rates (Wald χ2=7.41, df=1, p=0.007). Premenopausal women taking imipramine were significantly more likely to withdraw from the study than postmenopausal women taking imipramine (28 [29%] of 98 versus 2 [8%] of 25; Mantel-Haenszel χ2=5.24, df=1, p=0.02). Among women taking sertraline, a greater number of postmenopausal women withdrew from the study compared with premenopausal women (11 [22%] of 49 versus 26 [13%] of 201), but the difference was not statistically significant (Mantel-Haenszel χ2=2.50, df=1, p=0.11).

Responder analysis at endpoint by menopausal status showed that premenopausal women were significantly more likely to respond to sertraline than to imipramine (115 [57%] of 201 versus 41 [43%] of 96; Mantel-Haenszel χ2=6.31, df=1, p=0.01), whereas response rates to sertraline and imipramine in postmenopausal women were similar (27 [57%] of 47 versus 14 [56%] of 25; Mantel-Haenszel χ2=0.02, df=1, p=0.88). The interaction between menopausal status and treatment was not significant (Wald χ2=0.88, df=1, p=0.35).

When we used change in Hamilton depression scale score at endpoint as a measure of treatment response, premenopausal women again responded significantly better to sertraline than to imipramine (t test of ANOVA least squares means, t=2.65, df=360, p=0.008). Among postmenopausal women, there were no significant differences in change in Hamilton depression scale scores between those taking sertraline and those taking imipramine (t test of ANOVA least squares means, t=0.69, df=360, p=0.49). The interaction between menopausal status and treatment approached significance (ANCOVA F=3.24, df=1, 360, p=0.07).

Examination of the effects of oral contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy on response rates in premenopausal and postmenopausal women was attempted, but the group sizes were too small to allow statistical analysis.

Response Rates by Age and Gender

The men and women in the sample were divided by age into subgroups of those <40 years, 40–50 years, and >50 years. For men, imipramine response rates were found to be consistently higher than sertraline response rates across all age groups, but the differences did not reach statistical significance. For the women, response rates to sertraline and imipramine were nearly identical in the 40–50 and >50 age groups, whereas response rates to sertraline and imipramine in the <40 age group were 79 (61%) of 129 and 26 (40%) of 65, respectively, and the difference was statistically significant (Mantel-Haenszel χ2=7.94, df=1, p=0.005). It is noteworthy that 186 (96%) of the women age <40 years were premenopausal.

Discussion

This study is the first that we are aware of to report gender differences in treatment response to tricyclic antidepressants compared with SSRIs in patients with chronic depression. We found a significant interaction of gender and treatment for both response rates and dropout rates, with the highest response rates and the lowest dropout rates occurring in women taking sertraline and in men taking imipramine. The intent-to-treat response rate for women taking sertraline was 57%, compared to only 46% for women taking imipramine. In contrast, men responded significantly better to imipramine than to sertraline, with response rates of 62% and 45%, respectively. Significant differences in dropout rates were also found; women taking imipramine were significantly more likely to withdraw from the study than women taking sertraline. Because a significant interaction of gender and treatment was found by using both intent-to-treat and completer analyses, we did not conclude that the differences in response rates were due merely to differences in tolerability. Even women who were able to tolerate imipramine throughout the 12-week trial showed poorer response rates, compared with women who took sertraline. In addition, the time-to-response analysis, which appropriately adjusts for dropouts by using available data for each subject up until the time of dropout and then censors the subject, also supported this conclusion.

Our finding that women respond poorly to imipramine is consistent with other results reported in the literature (4–6). That women may respond better to an SSRI than a tricyclic has not been previously reported, although data presented by Steiner et al. (17) showed that women responded better to paroxetine than to imipramine. In contrast, Lewis-Hall et al. (18) noted that fluoxetine was better tolerated but no more effective than tricyclics in depressed women. It should be mentioned that no comparison data were given for men or for placebo in the latter study; an important point: the possible interactive effect of menopausal status was not taken into account. In patients with dysthymia, the superior response of women, compared with men, to sertraline has also been noted by Yonkers et al. (unpublished data).

Our data also showed gender differences in time to response, with men who took imipramine responding significantly more rapidly than women who took imipramine. These results are consistent with the study by Frank et al. (19), who reported that women were slower than men to respond to combination treatment with imipramine plus interpersonal psychotherapy. This latter finding is even more compelling if one considers that interpersonal psychotherapy is an effective treatment for depression, in and of itself (Klerman et al. [20], Elkin et al. [21], Thase et al. [22]), which would tend to blunt the gender difference in response rates to imipramine.

Several significant gender differences in types of adverse events were also noted in our study. Among subjects who took sertraline, women were more likely to report nausea and dizziness, and men tended to report dyspepsia, sexual dysfunction, and urinary frequency. Gender differences in adverse events due to imipramine were manifested in similar patterns, with women more likely to report nausea and men more likely to report urinary difficulties and sexual dysfunction. The tendency for men to report more sexual side effects while taking antidepressants has been noted previously (23). Sociocultural factors may contribute to this disparity, as women may be more reluctant to discuss sexual complaints.

Differences were also shown in response and dropout rates in pre- versus postmenopausal women. Premenopausal women responded significantly better to sertraline than to imipramine, whereas response rates to the two drugs in postmenopausal women were similar. Among those taking imipramine, premenopausal women were significantly more likely to discontinue treatment than postmenopausal women. These findings suggest that the gender differences in imipramine response found in our study were due primarily to poor response and tolerability in premenopausal women.

Previous studies have not specifically examined response by stratifying the data by subjects’ menopausal status; however, a poor response to imipramine in younger versus older women has been noted. In a study by Raskin (4), imipramine response in women differed by age group, although men responded favorably to the drug regardless of age. Imipramine was no more effective than placebo for women under age 40, who responded preferentially to phenelzine, whereas older women were as responsive as men to imipramine. Similarly, Thase et al. (24) reported no difference between response to psychotherapy alone and combined treatment with a tricyclic plus psychotherapy for women under age 40, whereas men showed a more favorable response to combined treatment across all age groups. The response to combined treatment among women over age 50 was comparable to that in men. The poorer results in younger women in the latter study may be explained by the use of tricyclics in the combined regimen.

Such differences in imipramine response by age among women but not men also emerged in our study when we divided the men and women into <40 years, 40–50 years, and >50 years age groups. Women showed a significantly higher response rate to sertraline than to imipramine in the <40 age group, whereas response rates to sertraline and imipramine were nearly identical in the other two age groups. These findings strongly suggest that the differences in response by menopausal status noted in our study were not attributable simply to age-dependent differences.

The underlying mechanism of these gender differences in treatment response is unclear. One explanation is that the serotonergic potency of sertraline may be important for young women. Serotonergic agents have demonstrated efficacy in depressive disorders unique to this age group, such as premenstrual dysphoric disorder (25). Second, it may be that depressive subtype (i.e., typical versus atypical depression) is the critical determinant of response differences, as suggested by Thase et al. (26). Women are more likely to present with atypical depressive symptoms (27), which have been shown to respond preferentially to SSRIs or MAOIs (28, 29); men, on the other hand, often have more classic neurovegetative features of depression, which are responsive to tricyclics.

A third explanation for gender differences in treatment response is that female sex hormones may have an effect in determining response. Specifically, female gonadal hormones may play a permissive or inhibitory role in antidepressant activity, e.g., enhancing response to SSRIs or inhibiting response to tricyclic antidepressants. Several studies have shown that estrogen enhances serotonergic activity (30, 31), and preliminary studies have suggested that estrogen augments SSRI response in postmenopausal women (32). Further research is clearly needed to determine the exact mechanisms of these differential antidepressant effects.

On the basis of our results, consideration should be given to both gender and menopausal status in selecting an antidepressant for a given patient with depression. Premenopausal women should be treated preferentially with SSRIs; men, on the other hand, may respond better to tricyclics. However, concerns about side effect profiles and lethality of overdose must also be considered. Postmenopausal women appear to respond equally well to either class of medication.

A major limitation of this study is the lack of a placebo control group. The inclusion of a placebo condition may have altered the interpretation of our results by uncoupling specific and nonspecific elements of therapeutic response (26). Our decision not to use a placebo group has been explained in detail elsewhere (12) and was based primarily on ethical considerations, demonstrated low placebo response rates among chronically depressed adults (33), and the fact that the primary aim of the study was to test the relative efficacy of the newer agent, sertraline, against a standard comparator. Other limitations must be noted. Because of the inclusion/exclusion criteria used in this clinical trial, the generalizability of our findings to patients with chronic depression in the general population may be compromised. Similarly, the restriction of our study group to patients with chronic major depression or double depression may limit the applicability of these findings to patients with other types of depressive disorders, such as acute or episodic depression. Finally, we did not have the statistical power needed to address the effects of oral contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy on response rates in premenopausal and postmenopausal women; these effects should be examined in future work.

Conclusions

The study results provide evidence of gender-specific differences in the efficacy and tolerability of antidepressant medications in the treatment of chronic depression. Specifically, women in our study responded significantly better to sertraline than to imipramine, whereas men responded significantly better to imipramine than to sertraline. Women also had more tolerability problems with imipramine, as well as a slower response time to that medication. On the basis of analyses of the effect of age and menopausal status on response rates, it appears that the gender difference was predominantly determined by differential responsivity to the two medications in premenopausal women. In clinical practice, both gender and menopausal status should be considered in the decision about which antidepressant to use for a depressed patient. Whether these gender differences in acute treatment response will be associated with differences in subsequent relapse or recurrence rates will be examined in future reports.

|

|

|

|

Received Dec. 23, 1998; revision received Feb. 8, 2000; accepted Mar. 13, 2000. From the Medical College of Virginia, Virginia Commonwealth University; Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, Calif.; the University of Pittsburgh and Western Psychiatric Institute, Pittsburgh; the Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn.; the Department of Psychology, Virginia Commonwealth University; Brown University, Providence, R.I.; the University of Arizona, Tucson; Quintiles, Inc., Research Triangle Park, N.C.; Pfizer, Inc., New York; and the College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University School of Medicine, New York. Address reprint requests to Dr. Kornstein, Department of Psychiatry, Medical College of Virginia, Virginia Commonwealth University, P.O. Box 980710, Richmond, VA 23298-0710; [email protected] (e-mail). This study was completed under contracts from Pfizer Pharmaceuticals to the following investigators: Martin B. Keller, M.D. (Program Director), Gabor I. Keitner, M.D., and Ivan W. Miller, Ph.D., Brown University; James H. Kocsis, M.D., and John C. Markowitz, M.D., Cornell University; Daniel N. Klein, Ph.D., Fritz Henn, M.D., and David Schlager, M.D., State University of New York at Stony Brook; James P. McCullough, Ph.D., and Susan G. Kornstein, M.D., Virginia Commonwealth University; Robert M.A. Hirschfeld, M.D., and James Russell, M.D., University of Texas, Galveston; Michael E. Thase, M.D., and Robert Howland, M.D., University of Pittsburgh; John S. Carman, M.D., psychiatry and research, Atlanta; A. John Rush, M.D., and George Trapp, M.D., University of Texas Southwestern; Alan F. Schatzberg, M.D., and Lorrin Koran, M.D., Stanford University; Alan J. Gelenberg, M.D., and Pedro Delgado, M.D., University of Arizona; John Feighner, M.D., Feighner Research Institute; and Jan A. Fawcett, M.D., and John Zajecka, M.D., Rush Institute for Mental Well-Being.

Figure 1. Rates of Response to Sertraline and Imipramine at Endpoint Among Men and Women With Chronic Depression in a 12-Week Double-Blind Treatment Studya

aEndpoint was the subject’s last study visit, with the last observation carried forwardSatisfactory therapeutic response was indicated by a 50% decrease in the Hamilton depression scale score, a Hamilton depression scale score ≤15, a Clinical Global Impression (CGI) severity scale score ≥3, and a CGI improvement scale score of 1 or 2 (corresponding to “very much” or “much improved”).

bSignificant interaction of gender and treatment (logistic regression Wald χ2=10.47, df=1, p=0.001).

cSignificantly higher response rate for sertraline than for imipramine (Mantel-Haenszel χ2=5.34, df=1, p=0.02).

dSignificantly higher response rate for imipramine than for sertraline (Mantel-Haenszel χ2=4.12, df=1, p=0.04).

1. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz M, Blazer DG, Nelson CB: Sex and depression in the National Comorbidity Survey, I: lifetime prevalence, chronicity and recurrence. J Affect Disord 1993; 29:85–96Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Weissman MM, Bland R, Joyce PR, Newman S, Wells JE, Wittchen HU: Sex differences in rates of depression: cross-national perspectives. J Affect Disord 1993; 29:77–84Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Regier DA, Boyd JH, Burke JD Jr, Rae DS, Myers JK, Kramer M, Robins LN, George LK, Karno M, Locke BZ: One-month prevalence of mental disorders in the United States: based on five Epidemiologic Catchment Area sites. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:977–986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Raskin A: Age-sex differences in response to antidepressant drugs. J Nerv Ment Dis 1974; 159:120–130Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Medical Research Council: Clinical trial of the treatment of depressive illness. Br Med J 1965; 1:881–886Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Hamilton JA, Grant M, Jensvold MF: Sex and treatment of depression, in Psychopharmacology and Women: Sex, Gender, and Hormones. Edited by Jensvold MJ, Halbreich U, Hamilton JA. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association Press, 1996, pp 241–260Google Scholar

7. Davidson J, Pelton S: Forms of atypical depression and their response to antidepressant drugs. Psychiatry Res 1986; 17:87–95Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Keller MB, Klerman GL, Lavori PW, Fawcett JA, Coryell W, Endicott J: Treatment received by depressed patients. JAMA 1982; 248:1848–1855Google Scholar

9. Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, Burnam MA, Rogers W, Daniels M, Berry S, Greenfield S, Ware J: The functioning and well-being of depressed patients: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA 1989; 262:914–919Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Kornstein SG, Schatzberg AF, Yonkers KA, Thase ME, Keitner GI, Ryan CE, Schlager D: Gender differences in presentation of chronic major depression. Psychopharmacol Bull 1995; 31:711–718Medline, Google Scholar

11. Kornstein SG, Schatzberg AF, Thase ME, Yonkers KA, McCullough JP, Keitner GI, Gelenberg AJ, Ryan CE, Hess AL, Harrison W, Davis SM, Keller MB: Gender differences in chronic major and double depression. J Affect Disord 2000; 60:1–11 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Rush AJ, Koran LM, Keller MB, Markowitz JC, Harrison WM, Miceli RJ, Fawcett JA, Gelenberg AJ, Hirschfeld RMA, Klein DN, Kocsis JH, McCullough JP, Schatzberg AF, Thase ME: The treatment of chronic depression, part 1: study design and rationale for evaluating the comparative efficacy of sertraline and imipramine as acute, crossover, continuation, and maintenance therapies. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59:589–597Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Keller MB, Gelenberg AJ, Hirschfeld RMA, Rush AJ, Thase ME, Kocsis JH, Markowitz JC, Fawcett JA, Koran LM, Klein DN, Russell JM, Kornstein SG, McCullough JP, Davis SM, Harrison WM: The treatment of chronic depression, part 2: a double-blind randomized trial of sertraline and imipramine. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59:598–607Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76-338. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976, pp 218–222Google Scholar

16. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J: An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961; 4:561–571Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Steiner M, Wheadon DE, Kreider MS, Bushnell WD: Antidepressant response to paroxetine by gender, in 1993 Annual Meeting New Research Program and Abstracts. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1990, p 176Google Scholar

18. Lewis-Hall FC, Wilson MG, Tepner RG, Koke SC: Fluoxetine vs tricyclic antidepressants in women with major depressive disorder. J Womens Health 1997; 6:337–343Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Frank E, Carpenter LL, Kupfer DJ: Sex differences in recurrent depression: are there any that are significant? Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:41–45Google Scholar

20. Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Rounsaville BJ, Chevron ES: Interpersonal Psychotherapy of Depression. New York, Basic Books, 1984Google Scholar

21. Elkin I, Shea MT, Watkins JT, Imber SD, Sotsky SM, Collins JF, Glass DR, Pilkonis PA, Leber WR, Docherty JP, Fiester SJ, Parloff MB: National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program: general effectiveness of treatments. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:971–982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Thase ME, Buysee DJ, Frank E, Cherry CR, Cornes CL, Mallinger AG, Kupfer DJ: Which depressed patients will respond to interpersonal psychotherapy? the role of abnormal EEG sleep profiles. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:502–509Link, Google Scholar

23. Montejo-Gonzalez AL, Llorca G, Izquierdo JA, Ledesma A, Bousono M, Calcedo A, Carrasco JL, Ciudad J, Daniel E, De La Gandara J, Derecho J, Franco M, Gomez MJ, Macias JA, Martin T, Perez V, Sanchez JM, Vicens E: SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction: fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, and fluvoxamine in a prospective, multicenter, and descriptive clinical study of 344 patients. J Sex Marital Ther 1997; 23:176–194Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Thase ME, Greenhouse JB, Frank E, Reynolds CF, Pilkonis PF, Hurley K, Grochocinski V, Kupfer DJ: Treatment of major depression with psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy-psychotherapy combinations. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:1009–1015Google Scholar

25. Kornstein SG: Premenstrual syndrome: an overview. Primary Psychiatry 1997; 4:56–60Google Scholar

26. Thase ME, Frank E, Kornstein SG, Yonkers KA: Gender differences in response to treatments of depression, in Gender and Its Effects on Psychopathology. Edited by Frank E. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association Press, 2000, pp 103–129Google Scholar

27. Kornstein SG: Gender differences in depression: implications for treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58(suppl 15):12–18Google Scholar

28. Quitkin FM, Stewart JW, McGrath PJ, Tricamo E, Rabkin JG, Ocepek-Welikson K, Nunes E, Harrison W, Klein DF: Columbia atypical depression: a subgroup of depressives with better response to MAOI than to tricyclic antidepressants or placebo. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1993; 21:30–34Medline, Google Scholar

29. Pande A, Birkett M, Fechner-Bates S, Haskett RF, Greden JF: Fluoxetine versus phenelzine in atypical depression. Biol Psychiatry 1996; 40:1017–1020Google Scholar

30. Kendall DA, Stancel GM, Enna SJ: The influence of sex hormones on antidepressant-induced alterations in neurotransmitter receptor binding. J Neurosci 1982; 2:354–360Medline, Google Scholar

31. Halbreich U, Rojansky N, Palter S, Twoek H, Hissin P, Wang K: Estrogen augments serotonergic activity in postmenopausal women. Biol Psychiatry 1995; 37:434–441Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Schneider LS, Small GW, Hamilton S, Bystritsky A, Nemeroff CB, Meyers BS (Fluoxetine Collaborative Study Group): Estrogen replacement and response to fluoxetine in a multicenter geriatric depression trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 1997; 5:97–106Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Kocsis JH, Friedman RA, Markowitz JC, Leon AC, Miller NL, Gniwesch L, Parides M: Maintenance therapy for chronic depression: a controlled clinical trial of desipramine. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:769–774Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar