Placebo-Controlled Trial of Sertraline in the Treatment of Binge Eating Disorder

Abstract

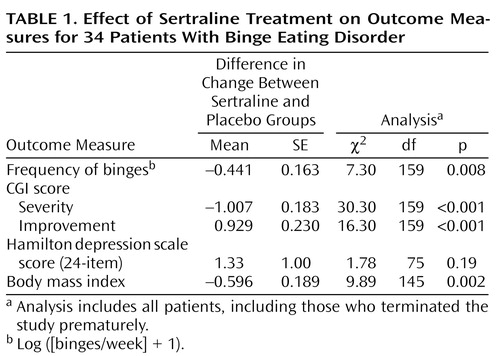

OBJECTIVE: The authors’ goal was to assess the efficacy of sertraline in the treatment of binge eating disorder.METHOD: Thirty-four outpatients with DSM-IV binge eating disorder were randomly assigned to receive either sertraline (N=18) or placebo (N=16) in a 6-week, double-blind, flexible-dose (50–200 mg) study. Except for response level, outcome measures were analyzed by random regression methods, with treatment-by-time interaction as the effect measure.RESULTS: Compared with placebo, sertraline was associated with a significantly greater rate of reduction in the frequency of binges, clinical global severity, and body mass index as well as a significantly greater rate of increase in clinical global improvement. Patients receiving sertraline who completed the study demonstrated a higher level of response, although the effect was not significant.CONCLUSIONS: In a 6-week trial, sertraline was effective and well tolerated in the treatment of binge eating disorder.

Although binge eating disorder has no established treatment (1), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) hold promise because they are effective in the treatment of bulimia nervosa (2, 3), a related condition. In a previous study (4), we found fluvoxamine to be superior to placebo in the treatment of binge eating disorder. Because of these observations, we conducted a placebo-controlled study of the SSRI sertraline in the treatment of binge eating disorder.

Method

The subjects were outpatients meeting DSM-IV criteria for binge eating disorder who also had experienced at least three binge eating episodes weekly for at least 6 months. We defined a binge according to DSM-IV criteria plus requiring the estimated number of calories to be at least 1500 kcal. The patients were between 18 and 60 years of age and had to weigh more than 85% of their ideal body weight (4). We excluded individuals who, on the basis of structured interview (5), had current anorexia nervosa, substance use disorder within the past 6 months, or history of psychosis or mania; risk of suicide; use of psychotropics within 2 weeks of random assignment to treatment or placebo groups; previous use of sertraline; or fewer than three binges in the week before random assignment to groups.

After a week of single-blind placebo administration, we assigned patients randomly to 6 weeks of double-blind treatment with sertraline or placebo. Study materials were capsules containing either 50 mg of sertraline or placebo. Subjects took one capsule daily for at least 3 days; thereafter the dose could be adjusted to between one and four capsules daily.

At each weekly visit, we assessed the number of binges since the last visit (using diaries); Clinical Global Impression (CGI) severity and improvement ratings; medication dose; and weight. We administered the 24-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale at baseline and weeks 2, 4, and 6. We categorized responses at week 6 on the basis of percentage of decrease in frequency of binges from baseline: remission=cessation of binges; marked=75%–99% decrease; moderate=50%–74% decrease; and none=less than 50% decrease.

For each outcome (except response category), we performed repeated measures random regression analyses (6, 7) comparing rate of change of outcome in the sertraline group and the placebo group (see reference 4). This was an intent-to-treat analysis because it included observations from all subjects (including dropouts) at all time points. To analyze frequency of binges, we used logarithmic transformation (log [(binges/week) + 1]) to stabilize variance. We compared differences in response categories using the exact trend test for two-by-k-ordered tables (6–8).

The institutional review board at the University of Cincinnati approved the protocol. All subjects signed informed consent forms after study procedures had been fully explained. Forty-five subjects entered the study; 34 were randomly assigned to active drug or placebo groups.

Results

Eighteen patients received sertraline, and 16 received placebo. There were no significant differences between groups at baseline in age, sex, body mass index, number of binges/week, Hamilton depression scale score, lifetime major depressive disorder, or current major depressive disorder. The mean age of the patients given sertraline was 43.1 years (SD=9.9), and the mean age of those given placebo was 41.0 (SD=12.2) (t=0.55, df=32, p=0.58). Sixteen (89%) of the patients given sertraline and all of the placebo patients were women (p=0.49, Fisher’s exact test). The mean body mass index of the sertraline group was 36.4 (SD=7.4), compared with 35.8 (SD=7.5) for the placebo group (t=0.23, df=32, p=0.82). The mean number of binges/week and its logarithmic transformation for the sertraline group were 7.6 (SD=4.8) and 2.04 (SD=0.48), respectively, compared with 7.2 (SD=5.8) and 1.97 (SD=0.52) for the placebo group (t=0.22, df=32, p=0.83, and t=0.40, df=32, p=0.69, respectively). The mean Hamilton depression scale score of the sertraline group was 6.4 (SD=3.9), compared with 7.5 (SD=8.4) for the placebo group (t=–0.50, df=32, p=0.62). Eleven (61%) of the patients given sertraline and seven (44%) of those given placebo had a lifetime diagnosis of major depressive disorder (p=0.30, Fisher’s exact test). Three (17%) of the sertraline patients and three (19%) of the placebo patients had a current diagnosis of major depressive disorder (p=1.00, Fisher’s exact test).

Eight patients withdrew during the study, all before the end of 4 weeks, for the following reasons: three for failure to make follow-up appointments; two for refusal to discontinue disallowed medications; one for refusal to obtain evaluation of a medical condition, one for a death in the family, and one for finding the study requirements burdensome. No patient withdrew because of an adverse medical event or worsening psychiatric status. The remaining 26 patients (13 in each group) completed the study. There were no significant differences between groups in incidence of adverse events, except that more sertraline-treated patients (N=7 [39%]) than patients given placebo (N=1 [6%] experienced insomnia (p=0.04, Fisher’s exact test).

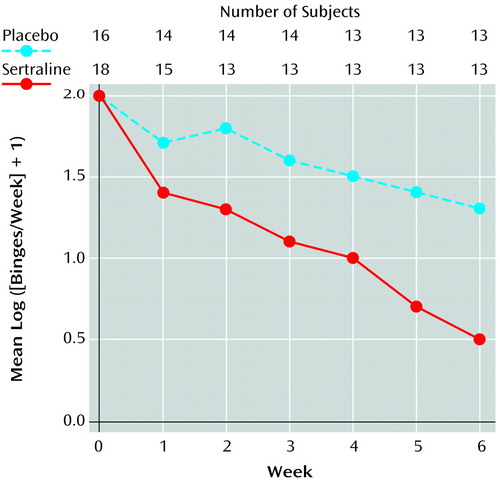

Over the course of treatment, the frequency of binges decreased in both groups, but more so in the sertraline group (Figure 1). Rates of decrease in the frequency of binges, improvement in CGI scores, and decrease in body mass index were significantly greater in the sertraline group than in the placebo group (Table 1). Estimated mean weight loss after 6 weeks of treatment for a patient 65.2 inches tall (the mean height for all patients) was 12.3 lb on sertraline, compared with 5.3 lb on placebo. Differences between groups remained significant even when the six patients with current major depressive disorder were excluded from the analysis. Among the patients who completed the study, sertraline was associated with a higher response level than placebo (seven versus two reached remission; two versus three had a marked response; three versus four had a moderate response; and none versus four had no response), but the difference did not reach statistical significance (p=0.06, exact trend test). At week 6, the mean number of binges/week was 1.13 (SD=1.56) in the sertraline group and 3.85 (SD=3.81) in the placebo group, and the mean log ([binges/week] + 1) was 0.54 (SD=0.66) in the sertraline group and 1.30 (SD=0.80) in the placebo group. The mean medication dose in the sertraline group was 187 mg (SD=30).

Discussion

Sertraline was associated with significantly greater rates of 1) decrease in frequency of binges, 2) decrease in severity of illness, 3) increase in global improvement, and 4) reduction in body mass index than placebo. Sertraline was also associated with a higher level of response; this difference approached significance. These results are similar to our findings in our previous controlled study of an SSRI in binge eating disorder (4).

Two limitations are 1) because duration of therapy was only 6 weeks, the results may not generalize to longer periods; 2) the finding of this and other studies (2, 4, 9) that many patients respond to placebo treatment suggests conservative use of medications in binge eating disorder.

|

Received Dec. 9, 1998; revisions received June 15, August 24, and November 16, 1999; accepted Dec. 10, 1999. From the Biological Psychiatry Program, Department of Psychiatry, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine; the Biological Psychiatry Laboratory, McLean Hospital, Belmont, Mass.; the Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston; and the Department of Biostatistics, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston. Address reprint requests to Dr. McElroy, Biological Psychiatry Program, 231 Bethesda Ave., P.O. Box 670559, Cincinnati, OH 45267-0559. Supported in part by a grant from Pfizer, Inc.

Figure 1. Mean Frequency of Binges for 34 Patients in a 6-Week Study of Sertraline Compared With Placebo for Binge Eating Disorder

1. deZwaan M, Mitchell JE, Raymond NC, Spitzer RL: Binge eating disorder: clinical features and treatment of a new diagnosis. Harvard Rev Psychiatry 1994; 1:310–325Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Hudson JI, Carter WP, Pope HG Jr: Antidepressant treatment of binge eating disorder: research findings and clinical guidelines. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57(suppl 8):73–79Google Scholar

3. Fluoxetine Bulimia Nervosa Collaborative Study Group: Fluoxetine in the treatment of bulimia nervosa: a multicenter, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:139–147Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Hudson JI, McElroy SL, Raymond NC, Crow S, Keck PE Jr, Carter WP, Mitchell JE, Strakowski SM, Pope HG Jr, Coleman BS, Jonas JM: Fluvoxamine in the treatment of binge-eating disorder: a multicenter placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1756–1762Google Scholar

5. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1996Google Scholar

6. Diggle PJ, Liang K, Zeger SL: Analysis of Longitudinal Data. Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press, 1995Google Scholar

7. SAS/STAT Software: Changes and Enhancements Through Release 6.12. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1997Google Scholar

8. Agresti A: Analysis of Ordinal Categorical Data. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1984Google Scholar

9. Stunkard A, Berkowitz R, Tanrikut C, Reiss E, Young L: d-Fenfluramine treatment of binge eating disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:1455–1459Google Scholar