Phenomenology and Outcome of Subjects With Early- and Adult-Onset Psychotic Mania

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined clinical differences between subjects with early-onset and adult-onset psychotic mania. METHOD: Subjects were from an epidemiologically derived, hospitalized sample who met criteria for definite bipolar disorder after 24 months of follow-up and whose index episode had been manic. Information collected regarding demographic characteristics, psychotic and depressive symptoms, childhood behavior problems and school functioning, substance/alcohol use disorders, and episode recurrence for two subgroups were compared: those whose illness first emerged before age 21 (early onset) (N=23) and those whose first episode occurred after age 30 (adult onset) (N=30). RESULTS: A larger proportion of the early-onset subjects were male, had childhood behavior disorders, had substance abuse comorbidity, exhibited paranoia, and experienced complete episode remission less frequently during 24-month follow-up than the adult-onset subjects. CONCLUSIONS: These data add to the body of evidence that has suggested that many subjects with early-onset psychotic mania have a more severe and developmentally complicated subtype of bipolar disorder.

Accumulating evidence suggests that substantial comorbidity and neurodevelopmental and premorbid psychosocial impairment accompany early-onset bipolar disorder (1–4). Less consistent evidence suggests that these early-onset patients have higher rates of psychosis than do subjects with older age at onset (5–9).

Attempts to address the question of age at onset and phenomenology are fraught with complications, such as whether the comparatively higher rates of psychosis in youth are a consequence of subject age at time of interview, age at onset of the disorder, the cutoff age for early versus late onset, or stage (early versus late) in the course of the disorder at which the subject is seen. A second complication in studies of psychosis concerns the challenging question of when to date onset (10). Does one date onset of bipolar disorder from first symptoms, first episode, first treatment, or first hospitalization? A substantial number of years may separate those phases (8). A previous study did not find an age-at-onset effect on clinical outcome (11), although none of the early-onset patients had been treated before age 19. A third complication regards the definition of comorbidity. Until recently, only adult axis I disorders were considered, but childhood psychopathology is clearly important (12, 13). An additional complication is the sample studied: most are “convenience” samples, which can introduce whatever admissions bias exists for that particular institution/location. Finally, there is the issue of time of diagnosis. Both schizophrenia and substance-induced mood disorder, with which mania may be confused, may require follow-up information past the first hospitalization/episode. Schizophrenia requires psychotic symptoms to persist without affective symptoms for 6 months; substance-induced mood disorder necessitates observation of the subject without drugs for up to a month before deciding on the influence of substances. This makes the point at which diagnosis is finalized very important.

In an attempt to address these complications, this study used subjects taken from an epidemiologically derived sample to assess similarities and differences in psychopathology in subjects hospitalized with a first episode of psychotic mania as an adolescent (between ages 15 and 20 inclusive) or as an adult (over age 30). The final study diagnosis was determined at the 24-month follow-up point to allow the illness to evolve—thus providing the most accurate diagnosis—and to examine diagnostic stability and change. Active substance abuse was not an exclusion criterion. This study tested the hypothesis that compared to those with onset in adulthood, subjects with early-onset (before age 21) psychotic mania show a more severe and complicated disorder as manifested by more diagnostic instability (14), higher rates of comorbidity (including childhood psychopathology), greater severity of psychosis, and higher rates of chronicity over a 2-year follow-up period (12).

METHOD

Sample

Described extensively elsewhere (14–16), the sample from which the two subgroups were selected comes from the Suffolk County Mental Health Project, a group of 695 subjects, 15–60 years of age, who were admitted to one of 12 psychiatric facilities in Suffolk County, N.Y., between September 1989 and December 1995 due to a psychotic episode. Exclusion criteria for this study were first psychiatric hospitalization more than 6 months before the index admission, moderate or severe mental retardation, and non-English-speaking status. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written consent was obtained from those judged competent to give consent. The lower age limit was set at 15, since only one of the participating hospitals admitted patients younger than 15 when the study began.

Measures

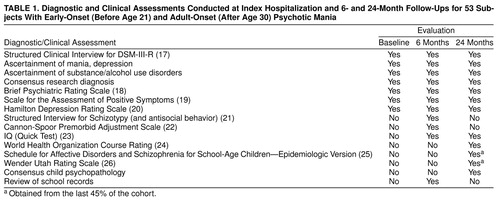

The assessment measures and their scheduled use are summarized in table 1.

Project interviewers were psychiatric social workers who were trained over the course of 3–6 months on using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) (17) and the other instruments used in this study. Interviews were taped (where allowed) for monitoring purposes. Additional reliability checks were provided by having a psychiatrist or the SCID trainer attend every 10th interview. The kappa for bipolar disorder diagnoses was 0.88 (16).

The initial/baseline interview with the subject usually took place at the hospital 1–3 weeks after admission. If the patient consented, interviews were also held with the patient’s psychiatrist and with a spouse, parent, or significant other. The medical record was reviewed at the time (and obtained once the patient was discharged). Interviewers also rated the severity of psychopathology with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (18), Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) (19), and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (20).

The 6-month follow-up evaluation included reassessments with the SCID and the other aforementioned rating scales, a clinical history review, and the collection of developmental information, psychosocial background information, and family history (27), obtained from the subject and a family member—a parent where possible. Interviews with a parent were conducted for 83% of the early-onset and 33% of the adult-onset patients. Developmental information included history of childhood illnesses, traumas, school placement, and treatment by professionals for general behavior or emotional problems. The Structured Interview for Schizotypy (21) and Cannon-Spoor measure of premorbid adjustment (22) provided the structure for obtaining most of the historical information. The Quick Test (23) was administered to estimate IQ.

In the absence of parent interviews for most of the adult-onset subjects, the validity of the subjects’ reports of school behavior was determined by comparing the self-reports to high school transcript information.

Follow-up telephone interviews to obtain information on current symptoms and treatment were conducted at 3, 12, 15, 18, and 21 months.

The final personal interview was conducted at 24 months and included reassessments with the SCID, the Quick Test (23), and other psychosocial and neuropsychological measures.

Consensus Diagnosis

Best-estimate DSM-IV diagnoses of the subject’s index psychotic episode and any co-occurring and/or lifetime disorders were made by two project psychiatrists independently by using information obtained from the SCID, significant other, medical charts, school records, and rating scales. Their report was presented at a meeting of all project psychiatrists, and consensus decisions were reached. This procedure was repeated at the 6- and 24-month follow-up points. A definite diagnosis was assigned only if the diagnostic criteria were fully met. At the 24-month diagnostic conference, a consensus was reached regarding the initial onset (acute versus nonacute) and pattern of episode recurrence after index episode by using ratings developed for the World Health Organization’s schizophrenia research program (24).

By the end of the 24-month period, each subject had a facility discharge diagnosis and a baseline, 6-month, and 24-month consensus research diagnosis. For this report, the 24-month consensus diagnosis was used to define the bipolar disorder group. There were 123 subjects who met criteria for definite bipolar disorder, 102 of whom whose index episode was manic in nature. This report compares two subgroups of these 102 subjects: those who were under 21 years of age at the time of their first episode (“early onset”; N=23), and those who were age 30 or over when their first episode occurred (“adult onset”; N=30).

Childhood Psychopathology

A best-estimate of childhood psychopathology was derived from the Structured Interview for Schizotypy (21), developmental information from parents, school records, and—for the last 45% of the group—the child version of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children—Epidemiologic Version (K-SADS-E) (25) and the Wender Utah Rating Scale (26). The Wender Utah Rating Scale is a self-rating instrument, scored in a Likert-scale format, that asks the subject to report on such childhood behaviors as attention problems, temper tantrums, impulsivity, mood, self-esteem, popularity, aggressive behavior, academic ability, and physical symptoms.

The Structured Interview for Schizotypy obtained frequency information on playing hooky, being expelled from school, being arrested, running away from home, and being drunk before age 15. School records were procured for all patients who gave consent (73.9% [N=17 of 23] of the early-onset subjects; 66.7% [N=20 of 30] of the adult-onset group). Placement in special education and poor school performance (defined either as a grade average of less than 70 according to the high school transcript or having dropped out of high school) was ascertained. Nine of the early-onset subjects and 15 of the adult-onset subjects had attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional-defiant disorder, or conduct disorder as determined by the K-SADS-E and the Wender Utah Rating Scale (26).

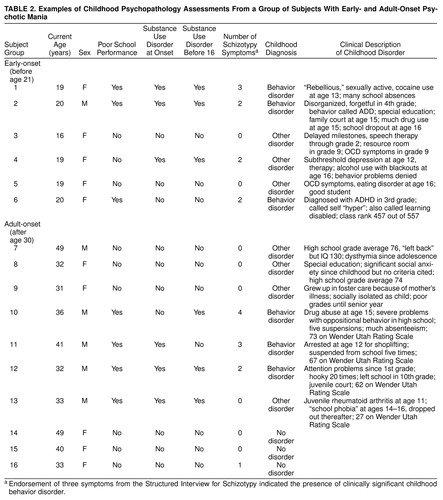

In the absence of systematic structured interview data on child psychiatric disorders for all subjects, only three classifications were made for childhood psychopathology: 1) the presence of clinically significant behavior disorders (signified by a persistent, markedly impairing disorder of hyperactivity/impulsivity that warranted referral or treatment, endorsement of at least three symptoms on the Structured Interview for Schizotypy, or evidence of substance/alcohol abuse before age 16 with behavior problems); 2) no evidence of psychopathology; and 3) presence of diagnostically ambiguous psychopathological symptoms, e.g., endorsement of one or two Structured Interview for Schizotypy symptoms, evidence of very early onset of mood disorder, evidence of significant anxiety, suicide gesture without evidence of a major depression, or emotional response to physical or sexual abuse. Instances of non-behavior-disorder psychopathology were also classified in this last category. Kappa for diagnosis of behavior disorder versus no/other psychopathology was 0.95. Examples of childhood clinical histories from subjects in all three groups are described in table 2.

Analysis

Early-onset subjects were compared with adult-onset subjects by using bivariate procedures. Because several variables (e.g., substance abuse, conduct disorder symptoms) are more often seen in men, relevant measures were analyzed with gender as a covariate.

RESULTS

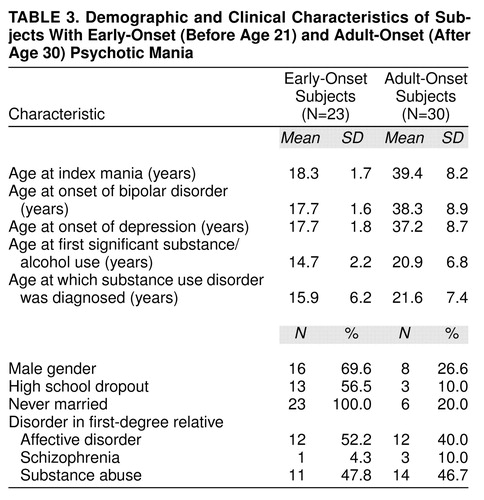

As expected, the mean ages at onset of bipolar disorder and the index manic episode were significantly different for the two groups (table 3). Six (26.1%) of the early-onset and five (16.6%) of the adult-onset subjects had a prior depressive episode.

Demographic Characteristics

Demographically, male subjects predominated in the early-onset group (69.6% versus 26.6%) (χ2=9.6, df=1, p<0.0001). Overall, however, the subjects were similar with respect to race (86.8% [N=46 of 53] of the subjects were Caucasian), household socioeconomic status (overall mean Hollingshead score=4.0, SD=1.66), and IQ at 6-month follow-up (overall mean=98.3, SD=14.3). As expected, given their mean age of 18, more of the early-onset subjects had not completed high school and were never married. Prevalences of affective disorder, schizophrenia, or substance abuse among first-degree relatives did not significantly differ between the two groups (table 3).

Childhood Conditions

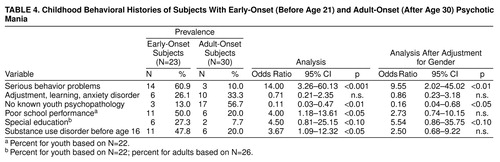

Subjects with early-onset psychotic mania were significantly more likely to have had a clinically significant behavior disorder in childhood (table 4). The average number of conduct disorder symptoms (out of a possible five) was 2.13 (SD=1.5) in the early-onset subjects and 0.78 (SD=1.12) in the adult-onset group (t=3.44, df=39, p<0.0001). These findings remained significant even after adjustment for gender (table 4).

More early- than adult-onset subjects had been in special education, but this difference was not statistically significant. However, as judged by high school transcripts in 66% of cases, poor school performance was noted somewhat more often in the early-onset subjects (50% versus 20.0%) (χ2=6.6, df=1, p<0.05). The significance disappeared after adjustment for gender. The validity of reports of childhood psychopathology in the adults was tested by comparing subject self-reports of school problems on the Wender Utah Rating Scale (26) against high school transcripts of poor school performance. Adults with poor school performance reported more school problems than those with average or better school performance (mean=12.4 [SD=6.8] versus mean=3.5 [SD=4.9]) (t=2.59, df=6.10, p=0.02).

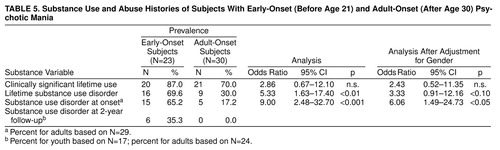

As noted in table 4, the early-onset subjects were significantly more likely to have a diagnosis of substance use disorder before age 16, which clearly antedated the onset of mood disorder (table 3). While early age of substance abuse was related to gender, substance abuse at index hospitalization remained a distinction for the early-onset subjects. table 5 shows that early-onset subjects were significantly more likely than adult-onset subjects to have substance use disorder present at the onset of their mood disorder. Although high lifetime rates of heavy substance use (70%) or abuse (30%) were seen in in the adult-onset subjects, most had ceased this behavior by the time they developed their index mania episode. At 24 months, six of the youth but none of the adults continued to meet criteria for substance use disorder.

Illness Severity

Early-onset subjects were significantly more likely than adult-onset subjects to report paranoid (100% [N=23] versus 80% [N=24], respectively) (χ2=5.1, df=1, p<0.05) and grandiose (73.9% versus 40%, respectively) (χ2=6.04, df=1, p<0.05) delusions, but not mood incongruent psychotic symptoms, formal thought disorder, or hallucinations. After timing of interview following admission was controlled for, only the BPRS scores (and not scores on the Hamilton depression scale or SAPS) were higher in the early-onset subjects (mean=41.5 [SD=11] versus mean=35.4 [SD=7.7]; F=6.21, df=22, 29, p<0.02). The duration of the initial hospitalization was not different for the two groups (mean=42.47 days [SD=47.3] and mean=36.08 days [SD=39.54], respectively).

Illness Course

Similar percentages of both groups had illness onsets that were defined as acute, subacute, or insidious, with acute onsets being the most common (60%) and insidious onsets the least (11%).

Among the subjects from whom information was obtained, more early- than adult-onset subjects experienced either partial or no remissions during the follow-up period (40.9% versus 10.3%, respectively). Conversely, more adult- than early-onset subjects experienced either a single episode (44.8% versus 22.7%, respectively) or more than one episode but with complete remission in between (44.8% versus 36.4%, respectively). Overall, the differences in remission status between groups were significant (χ2=6.96, df=2, p=0.03). Early-onset subjects spent significantly more time in the hospital over the 24-month follow-up than adult-onset subjects (mean=6.8 weeks [SD=4.52] versus mean=3.7 weeks [SD=3.0], respectively) (t=3.06, df=52, p=0.004, not counting one early-onset outlier who was hospitalized for 49 weeks). Manic episodes recurred more frequently in early-onset subjects (64.7% versus 12.5%), and depressive episodes recurred more frequently in adult-onset subjects (62.5% versus 17.6%) (χ2=10.1, df=2, p<0.01). Equal numbers of subjects experienced both kinds of episodes.

The early- and adult-onset subjects had similar rates of mania according to baseline consensus research diagnoses (56.5% and 73.3%, respectively) and facility discharge diagnoses (56.5% and 67.9%, respectively). At the 6-month research consensus diagnosis conference, however, 100% of the adult-onset subjects but only 81.8% of the early-onset group were identified as having bipolar disorder (χ2=5.72, p=0.03, Fisher’s exact test). Mixed episodes were much more likely to be experienced by the early-onset subjects (26.1% versus 3.3%) (odds ratio=10.23, 95% confidence interval=1.13–92.37) and had been the most difficult to diagnose, being initially diagnosed as psychosis not otherwise specified, drug-induced psychosis, or schizoaffective disorder.

DISCUSSION

This study selected a cohort of subjects with early- or adult-onset psychotic mania whose bipolar onset and first hospitalization were either relatively close in time or identical. Psychosis secondary to substance use was not an exclusion criterion. Diagnosis was based on both phenomenology and course rather than on the basis of initial hospitalization or structured interview only. The subjects were drawn from public, community, private, and university hospitals serving a county of 1.3 million. Parental reports were available for 83% of the early-onset subjects and one-third of the adult-onset subjects, although the latter group’s self-reporting of school problems was corroborated by information received from school transcripts. With these strengths and limitations, we conclude that young subjects with early-onset mania (before the age of 21) are more likely to be male, to have more complicated psychopathology (with early onset of behavior problems and substance abuse comorbidity, mixed episodes, and paranoid symptoms), and to spend more time in the hospital overall and less likely to remit completely over 24 months than subjects whose illness first emerges after age 30.

Comparing these findings with those of other reports is complicated. Other studies used diagnoses that were not based on structured interviews and 2-year course of illness, excluded subjects in whom substance abuse was complicating the admission (see reference 1 for review and reference 7), or described cultures in which substance use disorder in youth is absent (28). For instance, a recent study of youth with bipolar disorder in India, where substance abuse was absent, reported an equal gender ratio, a 63% rate of psychosis, and a very low rate of behavior disorder (7%) (28). It is unclear how far one can extrapolate the data from psychotic subjects to studies not limited to psychosis, although rates of co-occurring behavior disorders range from 22% to 59% (1). Not surprisingly, the percent of male subjects in the sample increases with the rate of behavior disorder comorbidity (from 44% to 65%).

If substance abuse is not an exclusion criterion from the study, male gender is strikingly prominent as an attribute of early-onset psychotic bipolar disorder. This is in contrast to the usually cited 1:1 gender ratio (29). With a higher representation of male subjects, childhood behavior problems and substance abuse also occur at higher rates in early-onset subjects.

Psychotic mania is similar to schizophrenia in two ways: onset occurs later in women than men (30), and the presence of substance/alcohol abuse appears to lower the age at onset (31). Although some might question whether these substance-abusing bipolar subjects are truly bipolar, the reason diagnoses were made at the 24-month time point was to ensure diagnostic accuracy.

Interest in frequency of psychotic symptoms was stimulated by the frequent misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder in young people, presumably because their manic symptoms were either obscured by the severity of their psychosis or were mistaken for schizophrenia. Older studies that compared early-onset subjects and adult subjects (usually over age 30) found higher rates of bizarre delusions and first-rank symptoms (5), more psychotic symptoms (9), or higher rates of schizoaffective diagnosis or “psychotic aggression” (8). The most recent study to examine rates of psychosis (7) did not find different rates of psychosis, but the average age at onset and first hospitalization of the early- and adult-onset groups were 12 and 15 years and 22 and 28 years, respectively. It is likely that the groups were, in fact, too developmentally similar to detect a difference.

In this study, the psychosis experienced by the early-onset subjects was not more severe, but paranoid and grandiose delusions were more common, which may explain why, in years past, young people with mania were diagnosed as having schizophrenia (6). By the time this study was concluded, the community clinicians were not distracted by psychotic symptoms, and diagnostic accuracy was similar in both groups. The bipolar diagnoses that were “missed” initially were largely changed because of information learned over the course of illness. Mixed episodes added to the diagnostic confusion. On the other hand, patients who were called “manic” at baseline who did not keep that diagnosis at follow-up were rediagnosed as having either schizophrenia spectrum or substance-induced mood disorders. In other words, clinicians who obtain a good history and who go though important inclusionary and exclusionary criteria obtain an accurate diagnosis more frequently in young people than in years past. However, there are some subjects who present with acute psychosis who need ongoing follow-up even after 6 months in order to finally make an accurate diagnosis.

The implications of early-onset academic and behavior problems are not yet clear. They may be manifestations of neurodevelopmental abnormalities (3) or of early onset mania (32, 33) or may represent a more complicated bipolar subtype (34). Either way, childhood behavior disorder psychopathology is likely to impact social, occupational, and school adjustment and to increase the likelihood of becoming involved with alcohol and drugs earlier and remaining involved with drugs longer (35). It is noteworthy that lifetime rates of drug and alcohol use and abuse were high in the adult-onset subjects but had not precipitated episodes of mania or depression and, by and large, had not continued to the time of index episode. This suggests different vulnerabilities in the early- and adult-onset subjects. Perhaps early-onset subjects at high risk for bipolar disorder have higher rates of affective instability that make them vulnerable to developing bipolar disorder, especially when persistently abusing substances at a very young age.

As measured by time in the hospital and frequency of incomplete remission and chronic course through the 24-month interval, early-onset (before age 21) psychotic mania requiring hospitalization appears to have a worse short-term prognosis than adult-onset (after age 30) mania. On the other hand, long-term studies of hospitalized manic patients suggest that short-term course is not necessarily predictive of ultimate functioning, especially in young people (8, 11, 36). Longer follow-up is thus needed. Indeed, this cohort will be reevaluated 4 years after their initial episode to examine long-term outcome.

Presented in part at the 88th annual meeting of the American Psychopathological Association, New York, March 5–7, 1998. Received Oct. 29, 1998; revision received June 15, 1999; accepted July 9, 1999. From the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, State University of New York at Stony Brook. Address reprint requests to Dr. Carlson, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, State University of New York at Stony Brook, Putnam Hall, Stony Brook, NY 11794-8790. Supported in part by NIMH grant MH-44801.

|

|

|

|

|

1. Carlson GA: Mania and ADHD: comorbidity or confusion. J Affect Disord 1998; 51:177–188Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Cannon M, Jones P, Gilvarry C, Rifkin L, McKenzie K, Foersterr A, Murray RM: Premorbid social functioning in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: similarities and differences. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1544–1550Google Scholar

3. van Os J, Takei N, Castle DJ, Wessely S, Der G, Murray RM: Premorbid abnormalities in mania, schizomania, acute schizophrenia and chronic schizophrenia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1995; 30:274–278Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Sigurdsson E, Fombonne E, Sayal K, Checkley S: Neurodevelopmental antecedents of early-onset bipolar affective disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 174:121–127Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Ballenger JC, Reus VI, Post RM: The “atypical” clinical picture of adolescent mania. Am J Psychiatry 1982; 139:602–606Link, Google Scholar

6. Joyce PR: Age of onset in bipolar affective disorder and misdiagnosis as schizophrenia. Psychol Med 1984; 14:145–149Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. McElroy SL, Strakowski SM, West SA, Keck PE Jr, McConville BJ: Phenomenology of adolescent and adult mania in hospitalized patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:44–49Link, Google Scholar

8. McGlashan TH: Adolescent versus adult onset of mania. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:221–223Link, Google Scholar

9. Rosen LN, Rosenthal NE, Van Dusen PH, Dunner DL, Fieve RR: Age at onset and number of psychotic symptoms in bipolar I and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1983; 140:1523–1524Google Scholar

10. Beiser M, Erickson D, Fleming JA, Iacono WG: Establishing the onset of psychotic illness. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1349–1354Google Scholar

11. Carlson GA, Davenport YB, Jamison K: A comparison of outcome in adolescent- and later-onset bipolar manic-depressive illness. Am J Psychiatry 1977; 134:919–922Link, Google Scholar

12. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Wozniak J, Mundy E, Mennin D, O’Donnell D: Is comorbidity with ADHD a marker for juvenile-onset mania? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:1046–1055Google Scholar

13. West SA, McElroy SL, Strakowski SM, Keck PE Jr, McConville BJ: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adolescent mania. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:271–273Link, Google Scholar

14. Carlson GA, Fennig S, Bromet EJ: The confusion between bipolar disorder and schizophrenia in youth: where does it stand in the 1990’s? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1994; 33:453–460Google Scholar

15. Bromet EJ, Schwartz JE, Fennig S, Geller L, Jandorf L, Kovasznay B, Lavelle J, Miller A, Pato C, Ram R: The epidemiology of psychosis: the Suffolk County Mental Health Project. Schizophr Bull 1992; 18:243–255Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Fennig S, Craig T, Lavelle J, Kovasznay B, Bromet EJ: Best-estimate versus structured interview-based diagnosis in first-admission psychosis. Compr Psychiatry 1994; 35:341–348Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID), I: history, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:624–629Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Woerner MG, Manuzza S, Kane JM: Anchoring the BPRS: an aid to improved reliability. Psychopharmacol Bull 1988; 24:112–117Medline, Google Scholar

19. Andreasen NC: Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS). Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1984Google Scholar

20. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Kendler KS, Lieberman JA, Walsh D: The Structured Interview for Schizotypy (SIS): a preliminary report. Schizophr Bull 1989; 15:559–571Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Cannon-Spoor HE, Potkin SG, Wyatt RJ: Measurement of premorbid adjustment in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1982; 8:470–484Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Ammons RB, Ammons CH: The Quick Test: provisional manual. Psychol Rep 1962; 11:111–161Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Sartorius N, Jablensky A, Korten A, Ernberg G, Anker M, Cooper JE, Day R: Early manifestations and first-contact incidence of schizophrenia in different cultures: a preliminary report of the initial evaluation of the WHO Collaborative Study on Determinants of Outcome of Severe Mental Disorders. Psychol Med 1986; 16:909–928Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Orvaschel H, Puig-Antich J, Chambers W, Tabrizi MA, Johnson R: Retrospective assessment of prepubertal major depression with the Kiddie-SADS-E. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry 1982; 21:392–397Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Wender PH: Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Adults. New York, Oxford University Press, 1995Google Scholar

27. Andreasen NC, Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Winokur G: The family history method using diagnostic criteria: reliability and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1977; 34:1229–1235Google Scholar

28. Srinath S, Janardhan Reddy YC, Girimaji SR, Seshadri SP, Subbakrishna DK: A prospective study of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents from India. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1998; 98:437–442Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Goodwin FK, Jamison KR: Manic Depressive Illness. New York, Oxford University Press, 1990Google Scholar

30. Hafner H, an der Heiden W, Behrens S, Gattaz WF, Hambrecht M, Loffler W, Maurer K, Munk-Jorgensen P, Nowotny B, Riecher-Rossler A, Stein A: Causes and consequences of the gender difference in age at onset of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1998; 24:99–113Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Addington J, Addington D: Effect of substance misuse in early psychosis. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1998; 172:134–136Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Wozniak J, Biederman J, Kiely K, Ablon JS, Faraone SV, Mundy E, Mennin D: Mania-like symptoms suggestive of childhood-onset bipolar disorder in clinically referred children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:867–876Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Strober M: Relevance of early age-of-onset in genetic studies of bipolar affective disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992; 31:606–610Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Carlson GA, Bromet EJ, Jandorf L: Conduct disorder and mania: what does it mean in adults. J Affect Disord 1998; 48:199–205Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Wilens TE, Biederman J, Mick E, Faraone SV, Spencer T: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is associated with early onset substance use disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis 1997; 185:475–482Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Coryell W, Norten SG: Mania during adolescence: the pathoplastic significance of age. J Nerv Ment Dis 1980; 168:611–613Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar