Evidence of Clozapine’s Effectiveness in Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to evaluate all available trial-based evidence on the effectiveness of clozapine in schizophrenia as compared with conventional neuroleptics. METHOD: All randomized, controlled trials comparing clozapine with a conventional neuroleptic in which there was satisfactory concealment of patients’ treatment allocation were located through electronic searches in all languages of several databases and through contacting authors of recent trials as well as the manufacturer of clozapine. At least two independent reviewers assessed trials for inclusion in the study and extracted data for meta-analysis. RESULTS: The review included 2,530 randomly assigned participants in 30 trials, most of them short-term. Clozapine-treated patients showed more clinical improvement and experienced significantly fewer relapses during treatment, although the risk of blood dyscrasias in long-term treatment may be as high as 7%. Scores on symptom rating scales showed greater improvement among clozapine-treated patients, who were also more satisfied with their treatment. However, there was no evidence that the superior clinical effect of clozapine is reflected in levels of functioning; on the other hand, global functional and pragmatic outcomes were frequently not reported. Clinical improvement was most pronounced in patients with treatment-resistant illness. CONCLUSIONS: This meta-analysis confirms that clozapine is more effective than conventional neuroleptics in reducing symptoms of patients with both treatment-resistant and nonresistant schizophrenia. Future trials should be long-term pragmatic community trials or should address the effectiveness of clozapine in special patient populations. An international standard set of outcomes, including pragmatic assessments of functioning, would greatly enhance the comparison and summation of trials and future assessments of effectiveness.

The current unmanageable amount of medical information has increased the need for research synthesis. The clinician needs reviews to efficiently integrate valid information and provide a basis for rational decision making (1). The use of explicit, systematic methods in reviews limits bias (systematic errors) and reduces random errors (simple mistakes), thus providing more reliable results from which to draw conclusions and make decisions (2). Publication biases (3) and language biases (4) may affect the conclusions in traditional reviews. Systematic reviews address these problems by using a comprehensive, unbiased search process. Furthermore, systematic reviews critically appraise the methodological quality of individual studies to limit bias. Empirical research has shown that lack of adequate allocation concealment in randomized trials is associated with bias (5). Meta-analysis—the use of statistical methods to summarize the results of independent studies—can provide more precise estimates of the effects of health care than those derived from the individual studies included in a review (6).

Clozapine is an atypical antipsychotic drug with a high risk of potentially fatal agranulocytosis. The sore need for an unbiased estimation of the effectiveness of clozapine based on the best available evidence, despite the availability of several overview papers, is highlighted by the fact that clozapine is increasingly used for severe schizophrenia because major randomized, controlled trials have demonstrated its superiority to traditional treatment in refractory cases (7–10). However, it has remained unclear whether clozapine is superior to conventional neuroleptics in nonrefractory schizophrenia. Previous traditional reviews of clozapine’s effectiveness have been restricted to the English language and thus are prone to biases, because studies with statistically significant treatment results are more likely to be published in English (11). This article presents the first systematic review of the effectiveness and safety of clozapine compared with conventional neuroleptics in the short-term treatment (up to and including 26 weeks) and long-term treatment (more than 26 weeks) of nonrefractory and refractory schizophrenia.

METHOD

This review considered randomized, controlled trials that compared clozapine at any dose with a conventional neuroleptic at any dose in the treatment of schizophrenia. Any conventional neuroleptic, excluding the “atypicals” such as amisulpride, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, sertindole, sulpiride, ziprasidone, and zotepine, was accepted as a control treatment.

The principal outcomes of interest were mortality, relapse, changes in mental state, behavioral changes, subjective well-being, social functioning, family burden, and adverse effects. Relapse was defined as a deterioration in mental state requiring further treatment or hospitalization. Hematological adverse effects were defined as any blood problem requiring withdrawal of the patient from the trial; leukopenia, defined as a white cell count less than 3,000/mm3; and neutropenia, defined as a granulocyte count less than 1,500/mm3.

Relevant randomized trials published in any language were identified by searching the following electronic databases without year limits: Biological Abstracts, the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Register of Trials, The Cochrane Library CENTRAL Register, Embase, LILACS, MEDLINE, and PsycLIT. The database-specific search strings we used were designated for identifying randomized, controlled trials relevant to the treatment of schizophrenia with the addition of phrases for clozapine. The exact search strings have been reported elsewhere (12).

All study citations identified by the searches were independently inspected by at least two reviewers, and full reports of the studies of agreed-upon relevance were obtained. Where disputes arose, the full report was also acquired for more detailed scrutiny. All of these full reports were then independently inspected by two reviewers (A.E. and K.W.) to assess their relevance to this review. The citation index SciSearch was searched for each selected trial in order to identify further studies, and the reference section of each selected study was inspected for additional works. The senior author of each trial published since 1980 and the manufacturer of clozapine (Novartis AG, Basel, Switzerland) were contacted for additional references, data, and information on unpublished trials. The company provided a list of trials but gave no access to additional data.

Because randomization concealment has been shown to affect trial outcomes (5, 13), two reviewers (M.C. and K.W.), independent of each other, graded the quality of allocation concealment according to the three quality categories described in the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook (14). The trials included in this review were those with low or moderate risk of bias (category A or B, respectively). Double-blind studies with no information on the randomization process were included in category B.

Two independent reviewers (M.C. and K.W.) extracted the data from the papers included. Again, any disagreement was discussed, the decisions were documented, and if necessary, the authors of the studies were contacted to help resolve the issues. The reviewers attempted to perform an intention-to-treat analysis. It was decided a priori that dropouts would be assigned the worst outcome, except in the case of mortality.

For dichotomous data a standard weighted estimate of the typical treatment effect across studies, the odds ratio—that is, the odds of an event occurring among treatment-allocated individuals versus the corresponding odds in the control group—was calculated. If the odds ratio equals 1, this indicates no difference between the groups compared. The odds ratio and its 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated with RevMan 3.0.1 software, with the use of the DerSimonian-Laird random effects model (15) in the case of heterogeneous outcomes and the Peto-modified Mantel-Haenszel fixed effects model (16) in the case of homogeneous outcomes. The random effects model includes both within-study sampling error and between-studies variation in the assessment of the confidence interval of the results, but the fixed effects model takes only within-study variation to influence the confidence interval. The Mantel-Haenszel chi-square test was used for calculating two-tailed statistical significance of outcomes.

As a measure of efficacy, the number-needed-to-treat statistic was also calculated. Number needed to treat indicates the number of patients who need to be treated to prevent one bad outcome and is the inverse of the absolute risk reduction (risk difference). In the case of adverse effects, the corresponding number needed to harm was calculated.

Heterogeneity—i.e., whether the differences among the results of trials were greater than would be expected by chance alone—was assessed visually from graphs and by the chi-square test of heterogeneity. A significance level of less than 0.10 was interpreted as evidence of heterogeneity. Sensitivity analyses were performed with the use of Meta-analyst 0.975 software (17). Finally, the presence of possible publication bias was visually assessed from funnel graphs.

To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to nonparametric continuous outcome data, standard deviations and means were required to be reported in the paper or to be obtainable from the authors, and the standard deviation, when multiplied by 2, had to be less than the mean (otherwise, the mean is unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the center of the distribution) (18). Data not satisfying these standards were not included in the data analysis. When authors of reports of trials did not report the standard deviation of an outcome variable at the end of the study, it was approximated by using the baseline standard deviation of the same variable.

The reviewers undertook six sensitivity analyses in order to detect any systematic differences between 1) trials using rigorous diagnostic criteria and trials using more pragmatic entry criteria; 2) analysis assuming that dropouts had a poor outcome and analysis of data from completers alone; 3) trials sponsored by the drug manufacturer and unsponsored studies; 4) trials comparing clozapine with low-potency neuroleptics and trials comparing clozapine with high-potency neuroleptics; 5) trials for patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia and trials for patients without this designation; and 6) trials using comparatively low doses of the control treatment and trials with equivalent doses of the control treatment.

RESULTS

The electronic searches resulted in 403 citations, from which 139 full reports were selected for evaluation by the reviewers. The detailed search result has been reported elsewhere (12). Further searches and contacts as described in the Method section identified 34 more citations of studies possibly relevant to this review. Novartis AG provided 19 references; all of them were already identified, and none provided further information.

Of the 173 articles, 112 were excluded, mostly because they had used an uncontrolled design. Upon inspection of the pool of remaining papers, 37 separate randomized, controlled trials comparing clozapine with conventional neuroleptic treatment were found. Two studies (19, 20) were then excluded because of diagnostically mixed study populations, and three trials (21–23) were excluded because of a lack of satisfactory concealment of allocation. Two papers (24, 25) were excluded because of a lack of extractable data. Thus, the review includes data on 2,530 randomly allocated participants from 30 separate trials (7–10, 26–62) dating from 1974 to 1998 (Table 1). Several studies had been published repeatedly, but every effort was made to identify them in order to avoid citation bias. A citation search of 57 references included in the SciSearch database yielded 1,094 references, but none of those not previously known to the reviewers met the inclusion criteria.

Five relatively recent trials (8, 10, 54–56) were long-term studies of more than 26 weeks’ duration, whereas the remainder all had a maximum length of 12 weeks. The vast majority of the trials were set in hospitals. To our knowledge, only two trials (56, 61) were performed in the community. Two long-term trials (8, 10) were hospital-based with postdischarge follow-up.

The following control treatments were used by the investigators: haloperidol (N=13), chlorpromazine (N=12), several neuroleptics (N=2), clopenthixol (N=1), thioridazine (N=1), and trifluoperazine (N=1). Five trials dating from before 1985 (26, 35, 38, 39, 42) used low doses of conventional neuroleptic drugs, which may have favored clozapine in the comparisons. Two of these studies (26, 38) used equal-milligram doses of clozapine and chlorpromazine, while the other three used comparatively low doses of haloperidol.

Trial design was generally good; most trials used a parallel-group design, but two (27, 37) included trials that applied a crossover design. It was not possible to extract data from the first phase of these crossover studies, except for mortality and relapse rates, because of incomplete reporting. Blinding was applied in most studies; 25 studies were double-blind, and only two studies (8, 54) lacked any blinding at all. Only two studies published before 1980 (39, 40) reported adequate concealment of random assignment to treatment. Four additional studies with adequate concealment (7, 10, 56, 59) were identified from more recent reports and personal communication with authors. At this time, all other studies included must be considered as studies with unclear concealment of random allocation and a moderate risk of bias.

On the basis of data from 19 trials with 1,833 participants, the weighted mean age of participants was estimated to be 37.6 years. Data on sex were reported for 1,888 participants, with a predominance of males (73%). Participants were diagnosed according to DSM criteria in 11 trials (Table 1). The remainder of the trials seem to have used a pragmatic approach to the diagnosis of schizophrenia. Seven trials (7, 8, 10, 49, 59, 60, 61) included only patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Only one of the 30 trials (59) focused on children or adolescents.

Data extraction in general was complicated by variability among studies in the reporting of outcomes and adverse effects. A frequent shortcoming was poor reporting of the cause or the number of dropouts. Eleven studies (7, 10, 26, 27, 35, 37, 39, 42–44, 59, 61) undertook intention-to-treat analysis in terms of both efficacy and adverse effects. In three additional studies (41, 47, 60), intention-to-treat analysis was performed in the assessment of adverse effects alone.

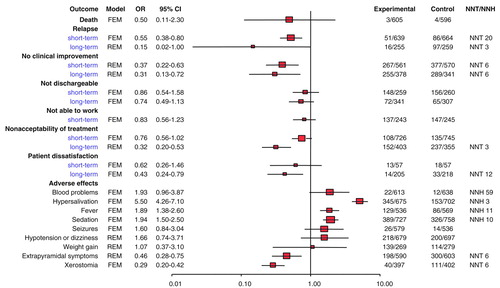

No difference between groups was found in 11 trials with data on mortality available. Four deaths occurred among 596 participants treated with conventional neuroleptics, compared with three deaths among 605 participants treated with clozapine (χ2=0.3, df=1, p=0.62) (Figure 1).

Clinical Outcome

Heterogeneous data on relapse prevention extracted from 22 studies (1,817 participants) favored clozapine (random effects odds ratio=0.4, 95% CI=0.2–0.8; number needed to treat=8; χ2=61.3, df=1, p<0.00001). The 19 short-term studies, however, had homogeneous data and also favored clozapine (χ2=9.2, df=1, p=0.002) (Figure 1). Pooling of three heterogeneous long-term studies (514 participants) did not show a significant difference in odds for relapse between treatment groups. The heterogeneity was caused by preliminary data derived from a rather small long-term study (55), which so far has not been completely reported.

Regarding clinical improvement, as defined by the researchers, analysis of the heterogeneous data (17 studies, 1,850 participants) favored clozapine (random effects odds ratio=0.4, 95% CI=0.2–0.6; number needed to treat=6; χ2=71.6, df=1, p<0.00001). The three heterogeneous long-term studies showed a slightly larger benefit for clozapine than the short-term studies (Figure 1). A major factor causing heterogeneity among studies may be variations in the control medication dosage. For example, in a long-term study (10) with a mean haloperidol dose of 28 mg/day, the participants in the control group improved to a greater extent (16%) than did those in a study with a modal haloperidol dose of 10 mg/day (improvement rate=6%) (56–58).

When homogeneous data from six short- and two long-term studies (1,167 participants) on readiness for hospital discharge were analyzed, no significant difference between treatment groups was found (odds ratio=0.8, 95% CI=0.6–1.1; χ2=2.1, df=1, p=0.15). Similarly, when data from five studies (488 participants) on ability to work were analyzed, no significant difference between treatment modalities was found (χ2=0.7, df=1, p=0.41) (Figure 1). No data on social functioning were available from any of the reports.

Acceptability of treatment was measured by the number of participants dropping out of the treatment groups. The overall acceptability of clozapine treatment was generally better than that of conventional neuroleptics, according to heterogeneous data available from 22 short-term studies and four long-term studies (2,229 participants). One source of heterogeneity is the different types of control treatment: clozapine’s acceptability was superior to that of low-potency neuroleptics but not to that of high-potency neuroleptics (see sensitivity analyses below). Clozapine did show a significant superiority in acceptability over conventional neuroleptics in long-term treatment (χ2=57.2, df=1, p<0.00001) but not in short-term treatment (χ2=3.0, df=1, p=0.08) (Figure 1). The dropout rates from long-term antipsychotic treatment were high: 38% from clozapine treatment and 67% from conventional neuroleptic treatment.

One possible explanation for the superior acceptability of clozapine is greater patient satisfaction. Participants’ satisfaction with treatment was better with clozapine than with conventional neuroleptics (odds ratio=0.5, 95% CI=0.3–0.8; number needed to treat=12; χ2=7.4, df=1, p=0.007), as expressed by those being treated in two short-term studies and one long-term study (537 participants) (Figure 1).

It was possible to extract heterogeneous continuous data on Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) total scores at trial end from 12 short-term studies (899 patients). Because the investigators used two different item scorings (scores of 0–6 and 1–7), a standardized mean difference was calculated, which favored clozapine (random standard mean difference=0.4, 95% CI=0.2–0.6). Only one long-term study (235 participants) (10) reported Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale endpoint scores, and these indicated a significantly better outcome with clozapine (mean difference=7, 95% CI=3–11). A summary of symptom scores in all 12 trials (1,134 participants) showed clozapine to be of greater benefit (random standard mean difference=0.4, 95% CI=0.2–0.6). Rating scale data on negative symptoms could be extracted from four trials only, totaling 164 participants. The researchers reported these data using several different scoring systems. The summary standard mean difference for effect on negative symptoms was 0.4 (95% CI=0.1–0.8) in favor of clozapine, but the small number of participants contributing to this result necessitates cautious interpretation of this statistically significant finding.

Adverse Effects

Thirteen trials with data on hematological problems reported problems more frequently in clozapine-treated patients, although statistical significance was not reached (χ2=2.1, df=1, p=0.14) (Figure 1). Twenty-two cases of hematological problems in 613 clozapine-treated individuals (3.6%) were reported. One clozapine-treated patient developed a drop in RBC; the remaining 21 had leukopenia, neutropenia, or agranulocytosis. Seventeen of the 21 patients with WBC problems were adults (frequency=2.8%), and the remainder were children or adolescents. In the single study dealing with this population (59), four of 10 clozapine-treated participants developed blood problems during the 6-week trial (number needed to harm=2.5). The reported rate of hematological problems in the pooled control group was 1.9% (N=12 of 638).

Treatment with clozapine commonly caused more hypersalivation (data from 15 studies), temperature increase (eight studies), and sedation (15 studies) when compared with treatment with conventional neuroleptics (Figure 1). The occurrence of dry mouth (eight studies) and extrapyramidal symptoms (16 studies) was more frequent in the control patients. No difference was found between clozapine and the conventional neuroleptic drugs for hypotension/dizziness (12 studies), seizures (eight studies), and weight gain (four studies).

Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia

An analysis of data from four homogeneous short-term studies (396 treatment-resistant participants) did not reveal any difference in relapse rates between the treatment groups (odds ratio=1.0, 95% CI=0.6–1.9; χ2=0.0, df=1, p=1.00), but one major long-term study (10) indicated an advantage for clozapine in preventing relapse (odds ratio=0.2, 95% CI=0.1–0.3; number needed to treat=3; χ2=56.8, df=1, p<0.001). Regarding clinical improvement, as defined by the authors of the original studies, the results of four homogeneous short-term studies with 370 patients favored clozapine (odds ratio=0.2, 95% CI=0.1–0.3; number needed to treat=4; χ2=43.9, df=1, p<0.000001); the results of two long-term studies (648 participants) also favored clozapine but to a lesser extent (odds ratio=0.5, 95% CI=0.3–0.7; number needed to treat=7; χ2=16.6, df=1, p=0.00004).

The BPRS total scores of five short-term studies with 429 treatment-resistant participants favored clozapine (standard mean difference=0.7, 95% CI=0.5–0.9). One long-term study (10) reported a benefit of clozapine as measured by Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total score. The combined standard mean difference for trial-end total symptom scores favored clozapine (standard mean difference=0.6, 95% CI=0.5–0.8). Data on negative symptom rating scale scores were available from four short-term trials and indicated a superior benefit of clozapine (standard mean difference=0.4, 95% CI=0.1–0.8).

Acceptability of treatment, as measured by the number of participants who dropped out, did not significantly differ between treatments in the five short-term trials with 436 treatment-resistant participants (odds ratio=1.2, 95% CI=0.7–2.1; χ2=0.3, df=1, p=0.58). However, the two long-term studies with 648 participants significantly favored clozapine (odds ratio=0.3, 95% CI=0.2–0.4; number needed to treat=3; χ2=56.5, df=1, p<0.00001). The dropout rates were 39% for long-term clozapine treatment and 70% for long-term treatment with conventional antipsychotics. In terms of dischargeability and readmission, however, no significant benefits of clozapine were observed in two long-term studies. No data on ability to work or social functioning were available from studies of treatment-resistant patients.

Sensitivity Analyses (Table 2)

In the comparison of trials that used stringent diagnostic criteria with studies that used a pragmatic approach to diagnosis, it was found that the clinical improvement benefit of clozapine was robust, but relapse prevention and treatment acceptability benefits did not reach a statistically significant difference in the stringent-diagnosis study group, which consisted mainly of U.S. studies.

Several of the trials reported some kind of connection with the manufacturer of clozapine. These studies were assumed to be sponsored studies. When studies were dichotomized into trials sponsored by the manufacturers and trials probably not funded by pharmaceutical companies, no difference in improver ratio between trial categories was observed. On the other hand, the odds ratios for relapse and dropout significantly favored clozapine in sponsored studies but not in unsponsored trials.

In the comparisons with low-potency control treatment and with high-potency control treatment, clozapine remained superior to both types of treatment with regard to clinical improvement. However, clozapine’s acceptability was superior only to that of low-potency neuroleptics, and the relapse-preventing benefit of clozapine was more homogeneous in trials comparing clozapine with low-potency drugs.

A sensitivity analysis of trials in patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia versus trials that did not define their participants as having treatment-resistant illness indicated that the former showed somewhat better clinical improvement than the latter. On the other hand, relapse rates and acceptability were significantly better only among clozapine-treated patients who were not treatment-resistant.

A sensitivity analysis was attempted also for the type of data analysis applied: intention-to-treat analysis or analysis of completers’ data only. However, available data were so limited that no conclusions on the influence of type of analysis were possible.

A post hoc sensitivity analysis on low-dose control treatment versus equivalent-dose control treatment was performed when it became clear that five studies used low doses of control treatment, which may have benefited the clozapine results. In the sensitivity analysis, the benefits of clozapine were maintained with regard to relapse rate, clinical improvement, and acceptability of treatment.

DISCUSSION

Although clozapine had a convincing clinical superiority to conventional neuroleptics in data from this review, it must be remembered that the effect size, at its best, was only modest. The improvement, as compared with conventional treatment, corresponds to approximately a 6-point difference in BPRS total score after up to 3 months of clozapine treatment. The clinical significance of a difference of this magnitude may be questioned. Furthermore, fewer than one-third of adult previously resistant patients treated with clozapine showed clinical improvement, defined as at least a 20% decrease in BPRS or Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total score. However, treatment-resistant children and adolescents seemed to respond more favorably, although currently this conclusion is based on one small trial (59). The modest effect of clozapine and the short duration of trials is reflected in the mainly disappointing results for indicators of global level of functioning.

Biases may affect the outcomes of meta-analyses as well as those of original studies. Every effort was made to reduce biases in this overview. A visual inspection of the distribution of the odds ratios among studies gave no indication of publication bias influencing this review. However, the generally poor quality of reporting in regard to both trial performance and trial outcome may have confounded our aim to avoid biases. For example, the method of random assignment to treatment was seldom described, and so 24 of the 30 studies were classified as having a moderate risk of selection bias and thus being more likely to favor the experimental treatment (5, 13).

In assessing the frequency of extrapyramidal adverse effects, one has to remember that some investigators (7, 10, 54, 55, 59, 61) used anticholinergic add-on medication in the control group to alleviate neurological adverse effects. To this extent the comparisons may have been biased in favor of the conventional neuroleptics. Even with this possibility, the clozapine-treated subjects displayed fewer extrapyramidal symptoms than those treated with conventional drugs.

Inadequate, researcher-assessed, symptom-oriented reporting of outcomes prevailed in the trials. Astonishingly, only three studies attempted to record patient satisfaction. The lack of reporting on important pragmatic global outcomes, such as mortality and ability to work and cope in the community, was striking. Data on mortality were missing in almost two-thirds of the studies, working ability was assessed in six trials only, and no trial reported patients’ ability to live on their own in the community or the impact on family burden. Furthermore, continuous data were frequently incompletely reported, lacking measures of variance. Adverse effects were often reported by means of scores on various rating scales, which made extraction of dichotomous data impossible. There is clearly a need for studies focusing not only on symptom outcomes but also on general and social functioning, family burden, and acceptability to patients as well, and for improved standards of trial reporting for authors, referees, and editors of journals. A strict adherence to the CONSORT statement on trial reporting (63) would greatly enhance the information value of reports and the possibilities of performing meta-analyses.

The majority of schizophrenic patients are treated in the community. One factor compromising the generalizability of this review is that 24 of the 30 studies took place only in hospitals. Not all of the conclusions of this review may be applicable to community treatment of schizophrenic patients.

Fewer than one-half of the included studies reported the use of explicit diagnostic criteria. The effect of differing diagnostic stringency was tested by sensitivity analysis, which revealed that the greater benefits of clozapine in relapse prevention and treatment acceptability do not reach statistical significance when stringent diagnostic criteria are applied. It may be argued that the overall conclusions of our review are biased in favor of clozapine because of our decision to include trials that applied a pragmatic diagnosis. Stringent diagnostic criteria are, however, not often used in everyday clinical practice, since the core symptoms of schizophrenia are relatively easy to recognize. We argue, therefore, that the data in this review may more accurately reflect general clinical effectiveness and that the generalizability of the results of the review is enhanced, not compromised, by the inclusion of trials with a pragmatic approach to diagnosis.

Twenty-one of the 30 studies had a duration of only 4–8 weeks. This short trial duration may have resulted in underreporting of both adverse effects and effectiveness. Since the risk of potentially fatal agranulocytosis is at its greatest after a few months of treatment (64), it was underreported in the short-term studies included. The data in this review suggest that the frequency of blood problems in short-term studies was 0.5% in adults and 40% in children and adolescents. Data from the long-term trials with a reported duration of at least 29 weeks indicate that the frequency of WBC problems was as high as 7.0% of the adult patients assigned to clozapine. The rate of leukopenia, defined as a WBC count less than 3000/mm3, was 2% in a series of 11,555 patients followed for at least 3 weeks and not more than 18 months; agranulocytosis developed in 0.6%, with an increased risk for female patients and older patients (64). Participants in the studies included in this review were mostly male and middle-aged. The surprisingly high overall WBC problem frequency of 2.8% in the adults in this review may reflect trial conditions with strict monitoring of blood counts.

Deficiencies in global and social functioning caused by schizophrenia require a long period to improve, and any beneficial effect of clozapine may thus be underestimated in short studies. Accordingly, this review found more advantageous clinical improvement rates and acceptability of clozapine in studies with a duration of more than 26 weeks than in short-term studies. However, no significant difference in readiness to leave the hospital was detected even in the long-term studies. It may be necessary to continue neuroleptic treatment for several months or years in large numbers of patients before measurable effects on the ability to live and work in the community can be achieved.

In patients with neuroleptic-resistant illness, clozapine showed a somewhat greater advantage in controlling symptoms. This is not surprising, since, by definition, the patients were nonresponders to conventional neuroleptic treatment. The weighted mean difference between short-term treatments in BPRS total score was about 7 points. There was no indication of a significant beneficial effect of clozapine on relapse frequency or dropout rates in the short-term treatment of previously resistant patients, but the outcomes of long-term treatment with clozapine were more beneficial.

The sensitivity analysis indicates that drug company sponsorship influences clozapine results beneficially, at least for some outcomes (Table 2). However, the difference in dropout rates may also be explained by the fact that most of the largest sponsored trials (6, 30–36, 49) used a less acceptable low-potency drug (chlorpromazine) as the control group treatment.

Because some studies used low doses of control treatment, an additional post hoc sensitivity analysis was performed comparing these trials and trials with adequate doses of control treatment. The results of the trials with a possibly inadequate dose of conventional neuroleptics were more homogeneously in favor of clozapine, but there was no evidence that including these trials in the review biased our results; the outcomes remained significantly in favor of clozapine even when five trials with a possibly inadequate dose of the control treatment were excluded from the analysis (Table 2).

CONCLUSIONS

This systematic review confirmed that clozapine is convincingly more effective than conventional neuroleptic drugs in reducing symptoms of schizophrenia and postponing relapse. The advantages of clozapine were seen both in patients previously resistant to treatment and in those not designated as resistant to neuroleptic drugs. However, on the basis of present knowledge, it is not possible to tell whether clozapine is superior in achieving a better level of functioning, with enhanced opportunities for discharge and improved ability to work. In long-term treatment, both the beneficial effects on symptoms and the cumulative incidence of hematological problems increase.

More community-based, long-term, pragmatic trials (65) rather than explanatory, randomized trials are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of clozapine for global and social functioning in the community. Furthermore, more randomized trials are needed in special groups such as children and mentally retarded patients with schizophrenia. The effectiveness of clozapine in comparison with conventional neuroleptics in hospitalized adults is now well established, and further hospital-based short-term trials would be a waste of resources.

In the studies included in our review, many important outcomes were rarely reported (satisfaction with treatment, readiness for discharge, and ability to work) or not recorded at all (social functioning and family burden). The typically reported outcomes were scores on various rating scales. Pragmatic trials, avoiding the need to use rating scales that are difficult to interpret, could answer crucial questions relating to general functioning, well-being, and satisfaction. The lack of reporting of relevant data and the reporting of heterogeneous scale scores are major obstacles to summing up data for assessment of clozapine’s effectiveness. There is a compelling need for an internationally agreed-upon set of standardized outcome measures for schizophrenia trials.

Presented in part at the Ninth Biennial Winter Workshop on Schizophrenia, Davos, Switzerland, Feb. 7–13, 1998. A previous version for the lay public has been published electronically in The Cochrane Library CD-ROM. Received June 5, 1998; revision received Dec. 7, 1998; accepted Dec. 15, 1998. From the Department of Psychiatry, University of Helsinki; the Faculty of Human Medicine, Damascus University, Syria; and the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group, Oxford, United Kingdom. Address reprint requests to Dr. Wahlbeck, Department of Psychiatry, University of Helsinki, Lappviksvägen, P.B. 320, FIN-00029 HUCH, Finland; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by Finska Läkaresällskapet (Finnish Medical Society) and Medicinska Understödsföreningen Liv och Hälsa, Finland. The authors thank Anja Roilas, Jack Barkman, Dr. Michael Phillips, and Dr. Emtithal Rezk, for help in retrieving and assessing the trials, and the following researchers, who provided further information on their trials: Xi-qing Bao, Jeffrey Bedwell/Sanjiv Kumra, Susan Essock, Freddy Howard/John M. Kane, Eckhardt Klieser, Ann Mortimer, and Robert Rosenheck.

|

|

FIGURE 1. Outcomes of Schizophrenic Patients Randomly Assigned to Short- or Long-Term Treatment With Clozapine (Experimental) or Conventional Neuroleptics (Control) in 30 Trialsa

aOR=odds ratio; CI=confidence interval; NNT=number needed to treat; NNH=number needed to harm; FEM=fixed effects model; REM=random effects model. Columns with headings Experimental and Control refer to numbers of subjects.

1. Mulrow CD: Rationale for systematic reviews. BMJ 1994; 309:597–599Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Oxman AD, Guyatt GH: The science of reviewing research. Ann NY Acad Sci 1993; 703:125–133Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Easterbrook PJ, Berlin JA, Gopalan R, Matthews DR: Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet 1991; 337:867–872Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Moher D, Fortin P, Jadad AR, Juni P, Klassen T, Le Lorier J, Liberati A, Linde K, Penna A: Completeness of reporting of trials published in languages other than English: implications for conduct and reporting of systematic reviews. Lancet 1996; 347:363–366Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG: Empirical evidence of bias: dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 1995; 273:408–412Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Sacks HS, Berrier J, Reitman D, Ancona-Berk VA, Chalmers A: Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. N Engl J Med 1987; 316:450–455Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, Meltzer H, Clozaril Collaborative Study Group: Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic: a double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:789–796Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Essock SM, Hargreaves WA, Dohm FA, Goethe J, Carver L, Hipshman L: Clozapine eligibility among state hospital patients. Schizophr Bull 1996; 22:15–25Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Essock SM, Hargreaves WA, Covell NH, Goethe J: Clozapine’s effectiveness for patients in state hospitals: results from a randomized trial. Psychopharmacol Bull 1996; 32:683–697Medline, Google Scholar

10. Rosenheck R, Cramer J, Xu W, Thomas J, Henderson W, Frisman L, Fye C, Charney D: A comparison of clozapine and haloperidol in hospitalized patients with refractory schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 1997; 337:809–815Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Egger M, Zellweger-Zahner T, Schneider M, Junker C, Lengeler C, Antes G: Language bias in randomised controlled trials published in English and German. Lancet 1997; 350:326–329Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Wahlbeck K, Cheine M, Essali MA: Clozapine vs typical neuroleptic medication for schizophrenia, in The Cochrane Library 1998, issue 4. Oxford, UK, Update Software (http://www.update-software.com/cochrane.htm)Google Scholar

13. Chalmers TC, Celano P, Sacks HS, Smith H Jr: Bias in treatment assignment in controlled clinical trials. N Engl J Med 1983; 309:1358–1361Google Scholar

14. Mulrow CD, Oxman A (eds): Cochrane Collaboration Handbook, in The Cochrane Library, 1997, issue 4. Oxford, UK, Update Software (http://www.update-software.com/ccweb/cochrane/revhb302.htm)Google Scholar

15. DerSimonian R, Laird N: Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986; 7:177–188Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Yusuf S, Peto R, Lewis J, Collins R, Sleight P: Beta blockade during and after myocardial infarction: an overview of the randomized trials. Progr Cardiovasc Dis 1985; 17:335–371Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Lau J, Chalmers TC: Meta-analyst 0.975, 1994 (public domain software available from [email protected])Google Scholar

18. Altman DG, Bland JM: Detecting skewness from summary information. BMJ 1996; 313:1200Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Angst J, Jaenicke U, Padrutt A, Scharfetter C: Ergebnisse eines doppelblindversuches von HF 1854 (8-Chlor-11-(4 methyl-1-piperazinyl)-5H-dibeno (b,e) (1,4) diazepine) im Vergleich zu Levomepromazin. Pharmakopsychiatrie, Neuro-Psychopharmakologie 1971; 4:192–200Crossref, Google Scholar

20. van Praag HM, Korf J, Dols LC: Clozapine versus perphenazine: the value of the biochemical mode of action of neuroleptics in predicting their therapeutic activity. Br J Psychiatry 1976; 129:547–555Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Bao XG: [A double-blind study on the effect of clozapine, penfluridol, and chlorpromazine in the treatment of schizophrenia] (Chinese). Chung Hua Shen Ching Ching Shen Ko Tsa Chih 1988; 21:274–276 Google Scholar

22. Ruiz Ruiz M: Estudio doble ciego comparativo entre clozapina y clorpromacina en las esquizofrenias. Arch Neurobiol (Madrid) 1974; 37:169–180Medline, Google Scholar

23. Yang WJ: [Three antipsychotic drugs in the treatment of schizophrenia—a controlled and double-blind study] (Chinese). Chung Hua Shen Ching Ching Shen Ko Tsa Chih 1988; 21:277–280, 318–319 Google Scholar

24. Li Y: [Application of NOSIE in the study of neuroleptic treatment] (Chinese). Chung Hua Shen Ching Ching Shen Ko Tsa Chih 1987; 20:325–327 Google Scholar

25. Nahunek K, Svestka J, Misurec J, Rodova A: Klinické zkusenosti s clozpinem [Clinical experience with clozapine]. Cesk Psychiatr 1975; 71:11–16Medline, Google Scholar

26. Leon CA, Estrada H: Efectos terapeuticos de la clozapina sobre los sintomas de psicosis. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatria 1974; 3:309–318Google Scholar

27. Gerlach J, Koppelhus P, Helweg E, Monrad A: Clozapine and haloperidol in a single-blind cross-over trial: therapeutic and biochemical aspects in the treatment of schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1974; 50:410–424Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Fischer-Cornelssen K, Ferner U, Steiner H: Multifokale Psychopharmakaprüfung. Arzneimittelforschung 1974; 24:1006–1007Google Scholar

29. Fischer-Cornelssen KA, Ferner UJ: An example of European multicenter trials: multispectral analysis of clozapine. Psychopharmacol Bull 1976; 12:34–39Medline, Google Scholar

30. Fischer-Cornelssen K, Ferner U, Steiner H: Multifokale Psychopharmakaprüfung (“Multihospital Trial”). Arzneimittelforschung 1974; 24:1706–1724Google Scholar

31. Dick P, Rémy M, Rey-Bellet JJ: Essai de comparaison de deux antipsychotiques: la chlorpromazine et la clozapine [Comparison of two antipsychotic drugs: chlorpromazine and clozapine]. Ther Umsch 1975; 32:497–500Medline, Google Scholar

32. Ekblom B, Haggstrom JE: Clozapine (Leponex) compared with chlorpromazine: a double-blind evaluation of pharmacological and clinical properties. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp 1974; 16:945–957Medline, Google Scholar

33. Niskanen P, Achté K, Jaskari M, Karesoja M, Melsted B, Nilsson LB, Routavaara M, Tamminen T, Tienari P, Vogel G: Results of a comparative double-blind study with clozapine and chlorpromazine in the treatment of schizophrenic patients. Psychiatria Fennica 1974; 307–313Google Scholar

34. Vencovsky E, Peterova E, Baudis P: Srovnáni terapeutického úcinku clozapinu s chlorpromazinem [Comparison of the therapeutic effect of clozapine and chlorpromazine]. Cesk Psychiatr 1975; 71:21–26Medline, Google Scholar

35. Honigfeld G, Patin J, Singer J: Clozapine antipsychotic activity in treatment-resistant schizophrenics. Advances in Therapy 1984; 1:77–97Google Scholar

36. Singer K, Law S: Comparative double-blind study with clozapine (Leponex) and chlorpromazine in acute schizophrenia. J Int Med Res 1974; 2:433–435Google Scholar

37. Gerlach J, Thorsen K, Fog R: Extrapyramidal reactions and amine metabolites in cerebrospinal fluid during haloperidol and clozapine treatment of schizophrenic patients. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1975; 40:341–350Crossref, Google Scholar

38. Chiu E, Burrows G, Stevenson J: Double-blind comparison of clozapine with chlorpromazine in acute schizophrenic illness. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 1976; 10:343–347Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Ciurezu T, Ionescu R, Nica-Udangiu S, Niturad D, Oproiu L, Tudorache D, Popovici I, Curelaru S: Étude clinique en “double blind” du HF 1854 (=LX 100-129=clozapine=Leponex) comparé à l´halopéridol. Neurol Psychiatr (Bucur) 1976; 14:29–34Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Guirguis E, Voineskos G, Gray J, Schlieman E: Clozapine (Leponex) vs chlorpromazine (Largactil) in acute schizophrenia (a double-blind controlled study). Curr Ther Res 1977; 21:707–719Google Scholar

41. Itoh H, Miura S, Yagi G, Sakurai S, Ohtsuka N: Some methodological considerations for the clinical evaluation of neuroleptics—comparative effects of clozapine and haloperidol on schizophrenics. Folia Psychiatr Neurol Jpn 1977; 31:17–24Medline, Google Scholar

42. Erlandsen C: Utprøving av et nytt nevroleptikum, Leponex (clozapin) hos schizofrene med lang sykehistorie. Nordic J Psychiatry 1981; 35:248–253Crossref, Google Scholar

43. Shopsin B, Klein H, Aaronsom M, Collora M: Clozapine, chlorpromazine, and placebo in newly hospitalized, acutely schizophrenic patients: a controlled, double-blind comparison. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1979; 36:657–664Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Klein H, Aronson M, Shopsin B: Clozapine: double-blind controlled trial in the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychopharmacol Bull 1978; 14:12–15Medline, Google Scholar

45. Gelenberg AJ, Doller JC: Clozapine versus chlorpromazine for the treatment of schizophrenia: preliminary results from a double-blind study. J Clin Psychiatry 1979; 40:238–240Medline, Google Scholar

46. Xu WR, Bao-long Z, Qui C, Mei-fang G: A double-blind study of clozapine and chlorpromazine treatment in the schizophrenics. Chinese J Nervous and Ment Disease 1985; 11:222–224Google Scholar

47. Claghorn J, Honigfeld G, Abuzzahab FS Sr, Wang R, Steinbook R, Tuason V, Klerman GL: The risks and benefits of clozapine versus chlorpromazine. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1987; 7:377–384Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Potter WZ, Ko GN, Zhang LD, Yan W: Clozapine in China: a review and preview of US/PRC collaboration. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1989; 99(suppl):S87–S91Google Scholar

49. Klieser E, Schönell H: Klinisch-pharmakologische Studien zur Behandlung schizophrener Minussymptomatik, in Neuere Ansätze zur Diagnostik und Therapie schizophrener Minussymptomatik. Edited by Möller H-J, Pelzer E. Berlin, Springer-Verlag, 1990, pp 217–222Google Scholar

50. Stein D, Schönell H, Klieser E: Haloperidol zur Behandlung des systematisierten Wahns chronisch schizophrener Patienten, in Biologische Psychiatrie 2: Drei-Länder-Symposium für Biologische Psychiatrie. Edited by Saletu B. Stuttgart, Germany, Georg Thieme Verlag, 1989, pp 268–270Google Scholar

51. Liu BL, Chen YY, Yang DS: [Effects of thioridazine on schizophrenics and clinical utility of plasma levels] (Chinese). Chin J Neurol Psychiatry 1994; 27:364–367Google Scholar

52. Klieser E, Strauss WH, Lemmer W: The tolerability and efficacy of the atypical neuroleptic remoxipride compared with clozapine and haloperidol in acute schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1994; 380:68–73Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53. Klieser E, Lehmann E, Heinrich K: Risperidone in comparison with various treatments of schizophrenia, in Serotonin in Antipsychotic Treatment: Mechanisms and Clinical Practice: Medical Psychiatry, vol 3. Edited by Kane JM, Möller H-J, Awouters F. New York, Marcel Dekker, 1996, pp 331–343Google Scholar

54. Lee MA, Thompson PA, Meltzer HY: Effects of clozapine on cognitive function in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55(Sept suppl B):82–87Google Scholar

55. Tamminga CA, Thaker GK, Moran M, Kakigi T, Gao X-M: Clozapine in tardive dyskinesia: observations from human and animal model studies. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55(Sept suppl B):102–106Google Scholar

56. Kane JM, Schooler NR, Marder S, Wirshing W, Ames D, Umbricht D, Safferman A, Baker R, Ganguli R: Efficacy of clozapine versus haloperidol in a long-term clinical trial (abstract). Schizophr Res 1996; 18:127Crossref, Google Scholar

57. Marder SR, Kane JM, Schooler NR, Wirshing WC, Baker R, Ames D, Umbricht D, Ganguli R, Borenstein M: Effectiveness of clozapine in treatment resistant schizophrenia (abstract). Schizophr Res 1997; 24:187Crossref, Google Scholar

58. Wirshing WC, Baker R, Umbricht D, Ames D, Schooler N, Kane J, Marder SR, Borenstein D: Clozapine vs haloperidol: drug intolerance in a controlled six month trial (abstract). Schizophr Res 1997; 24:268Crossref, Google Scholar

59. Kumra S, Frazier JA, Jacobsen LK, McKenna K, Gordon CT, Lenane MC, Hamburger SD, Smith AK, Albus KE, Alaghband-Rad J, Rapoport JL: Childhood-onset schizophrenia: a double-blind clozapine-haloperidol comparison. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:1090–1097Google Scholar

60. Hong CJ, Chen JY, Chiu HJ, Sim CB: A double-blind comparative study of clozapine versus chlorpromazine in Chinese patients with treatment-refractory schizophrenia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1997; 12:123–130Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

61. Buchanan BW, Breier A, Kirkpatrick B, Ball P, Carpenter WT Jr: Positive and negative symptom response to clozapine in schizophrenic patients with and without the deficit syndrome. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:751–760Link, Google Scholar

62. Breier A, Buchanan RW, Kirkpatrick B, Davis OR, Irish D, Summerfelt A, Carpenter WT Jr: Effects of clozapine on positive and negative symptoms in outpatients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:20–26Link, Google Scholar

63. Begg C, Cho M, Eastwood S, Horton R, Moher D, Olkin I, Pitkin R, Rennie D, Schulz KF, Simel D, Stroup DF: Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials: the CONSORT statement. JAMA 1996; 276:637–639Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

64. Alvir JMJ, Jeffrey PH, Lieberman A, Safferman AZ, Schwimmer JL, Schaaf JA: Clozapine-induced agranulocytosis: incidence and risk factors in the United States. N Engl J Med 1993; 329:162–167Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

65. Roland M, Torgerson DJ: What are pragmatic trials? BMJ 1998; 316:285Google Scholar