Growing Up With ADHD Symptoms: Smooth Transitions or a Bumpy Course?

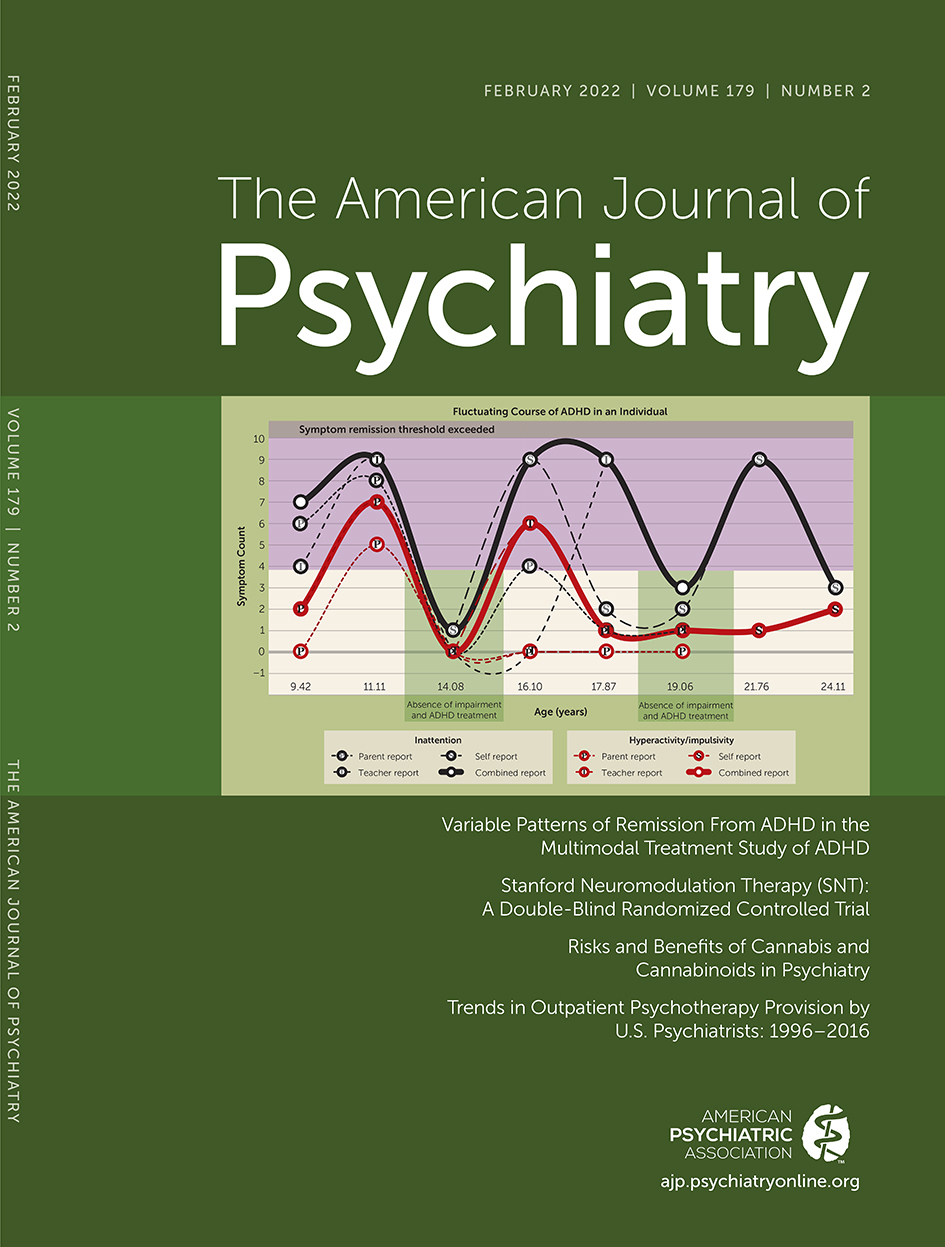

Children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) either grow out of the disorder or show symptom persistence throughout adolescence into adulthood (1, 2). It is probably widely assumed, though largely untested, that these symptomatic changes are gradual and relatively linear. Zig-zagging in and out of the diagnosis of ADHD during adolescence and early adulthood would likely not be expected to emerge as the dominant trajectory. However, by following a cohort of 558 children with ADHD from ages 8 to 25, Sibley et al. (3) provide, in this issue of the Journal, strong evidence that the course of ADHD may indeed be markedly uneven. Using rich longitudinal data, they chart individual diagnostic trajectories and find that sustained diagnostic persistence and sustained remission are uncommon courses, characterizing only 20% of youths with ADHD. Instead, the most common trajectory was of ADHD diagnoses that wax and wane, moving fluidly between syndromic, symptomatic, and asymptomatic states. Indeed, while a third of the cohort attained remission at one time point, around 60% of these youths showed a later recurrence of either symptoms or the full syndrome. Thus, remission was often transient and did not equate with recovery. The findings suggest that ADHD may differ from other neurodevelopmental disorders that are characterized either by mainly gradual improvement, such as tic disorders (4), or by relative syndromic stability, such as autism spectrum disorders (5). Indeed, the study raises the question of whether ADHD is more akin to a recurrent mood disorder, with phases of acute symptoms, improvement, and relapse.

There has been an increased recognition of the fluctuant nature of ADHD symptoms over time. While DSM-IV referred to subtypes of ADHD, DSM-5 refers to presentations, recognizing that symptoms are not stable traits but often change within individuals across their lifespan (6). Additionally, a handful of longitudinal studies have reported diagnostic instability even in adulthood (7). However, the Sibley et al. study provides the most detailed delineation to date of the adolescent course of ADHD. Nearly all previous longitudinal studies included participants for whom two or three observations were available. Such data allow complex, nonlinear trajectories to be defined at a group level, but only linear trajectories can be drawn at the individual level. By contrast, in the Sibley et al. study, there was an average of six observations per subject, which allows considerable complexity to be detected in individual-level diagnostic trajectories. Strikingly, complexity emerges as the rule, not the exception.

The authors anticipate and discount several explanations for this diagnostic instability. For example, they ensure that the diagnostic fluctuations reflect neither medication changes nor the emergence and resolution of comorbid disorders. Nonetheless, it is worth noting four features in the study’s design and analyses. First, the diagnosis of ADHD was based on questionnaire data rather than clinical interviews. Clinical judgment might better discern a more stable underlying trend in symptom change, particularly if conducted by the same clinician over time. Second, mindful of clinical applications, the authors focused on shifts in ADHD diagnosis rather than changes in symptom number and severity. While reasonable, this approach means that information is lost, as the quasi-continuous measure of symptoms is reduced to dichotomous diagnostic decisions. As discussed later, a delineation of trajectories based on symptoms may provide further, complementary insights. Third, the definition of prolonged remission required agreement between three raters (self, parent, teacher) on the absence of symptoms across multiple time points. By contrast, recurrence required only one rater to validate symptom presence at one time point. While this imbalance in symptom definition might contribute to the low rate of sustained remission, it cannot explain the equally low rate of persistence. Finally, the authors call for an extension and replication of this fascinating diagnostic pattern in other cohorts before generalizing the finding. For example, the study enrolled only patients with a combined presentation ADHD at baseline, and thus does not examine the full spectrum of the disorder. These considerations aside, the study’s central finding is striking, and if found in other cohorts, the fluctuant, almost idiosyncratic diagnostic trajectories of ADHD raise important issues for our scientific and clinical understanding of the disorder.

Considering the science of ADHD, the first step in understanding the etiological factors behind different ADHD lifetime courses is to identify subgroups characterized by shared natural histories. The Sibley et al. study suggests that a simple dichotomy of persisting versus remitting ADHD may be inadequate, and further subgroups will be needed. In this regard, it seems likely that distinct subgroups with similar trajectories could be identified even among those who show a diagnostic “wax and wane.” Techniques for extracting these trajectory subgroups will work better if applied to the finer-grained measures of symptom severity rather than diagnostic categories, and these techniques can model nonlinear trajectories (including growth curves). However, even with such modeling, a proportion may have symptom trajectories that cannot meaningfully be captured by a recognizable line or curve. One of the natural histories of ADHD may be a “zig-zagging” course.

What could be driving fluctuating diagnostic trajectories or, more generally, unstable ADHD symptoms during adolescence? The authors point to environmental factors. This is akin to a diathesis-stress model, in which genetic risk for ADHD is expressed in stressful environments but is more muted in advantageous contexts (8). The fluctuant course may also represent enhanced genetic susceptibility to the environment, arising from the individual carrying a higher number of “plasticity” alleles (which may only partly overlap with those conferring ADHD risk). In this susceptibility model of gene-environment interactions, heightened sensitivity and adverse outcomes in stressful environments is counterbalanced by the tendency to thrive in more optimal settings.

Which cognitive features might be at play? ADHD has been associated with differences in the development of key executive functions, particularly working memory and response inhibition (9, 10). However, it is hard to see how some measures of these skills, such as visuospatial working memory span, could show the degree of instability during adolescence needed to account for the marked diagnostic instability. Cognitive measures that are more variable are more plausible candidates. For example, those with ADHD show more variability than those who are unaffected in the time taken to make responses during prolonged, repetitive tasks (11). This intrasubject variability in response time is measured on the order of milliseconds, and as a marker of momentary lapses of attention, might show marked shifts during adolescence that could either reflect or drive fluctuating ADHD symptoms.

And what of the brain? Relatively stable anatomic or white matter microstructural features can provide valuable insights into the onset and final adult outcomes of ADHD (12). However, more dynamic processes of brain function, particularly developmental changes in the interactions between the brain’s major functional networks, seem better poised to help explain symptom shifts during adolescence. Large-scale longitudinal studies such as the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study will be pivotal in parsing the relationships between fluctuations in neural and cognitive functioning and changes in ADHD diagnoses over time.

Finally, which environmental factors could precipitate diagnostic shifts? The authors point to events such as academic transitions. All clinicians will be familiar with the teenager whose underlying symptoms of inattention become markedly impairing after a move to a school with more exacting academic demands. This possibility can be tested empirically by applying techniques that use longitudinal data to identify “breakpoints” in trajectories and seeing if these align with candidate environmental factors or events.

The study provides clinicians with yet another reason to ensure that youths with ADHD have regular symptom assessments, to be watchful for those whose remitted ADHD re-emerges, and to be prepared at times for a highly uneven, bumpy course of ADHD symptoms.

1 : Children and adolescents with ADHD followed up to adulthood: a systematic review of long-term outcomes. Acta Neuropsychiatr 2021; 33:283–298Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 : The age-dependent decline of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis of follow-up studies. Psychol Med 2006; 36:159–165Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 : Variable patterns of remission from ADHD in the Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD. Am J Psychiatry 2022; 179:142–151Link, Google Scholar

4 : Course of tic disorders over the lifespan. Curr Dev Disord Rep 2021; 8:121–132Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 : Outcomes in adolescents and adults with autism: a review of the literature. Res Autism Spectr Disord 2011; 5:1271–1282Crossref, Google Scholar

6 : Changes in the definition of ADHD in DSM-5: subtle but important. Neuropsychiatry (London) 2013; 3:455–458Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 : Persistence and remission of ADHD during adulthood: a 7-year clinical follow-up study. Psychol Med 2015; 45:2045–2056Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 : Defining the environment in gene-environment research: lessons from social epidemiology. Am J Public Health 2013; 103(Suppl 1):S64–S72Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 : Validity of the executive function theory of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review. Biol Psychiatry 2005; 57:1336–1346Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 : Heterogeneity in development of aspects of working memory predicts longitudinal attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptom change. J Abnorm Psychol 2017; 126:774–792Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 : Reaction time variability in ADHD: a meta-analytic review of 319 studies. Clin Psychol Rev 2013; 33:795–811Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 : Adolescent attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: understanding teenage symptom trajectories. Biol Psychiatry 2021; 89:152–161Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar