Subthreshold Hypomanic Symptoms in Progression From Unipolar Major Depression to Bipolar Disorder

Abstract

Objective:

The authors assessed whether subthreshold hypomanic symptoms in patients with major depression predicted new-onset mania or hypomania.

Method:

The authors identified 550 individuals followed for at least 1 year in the National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Depression Study with a diagnosis of major depression at intake. All participants were screened at baseline for five manic symptoms: elevated mood, decreased need for sleep, unusually high energy, increased goal-directed activity, and grandiosity. Participants were followed prospectively for a mean of 17.5 years and up to 31 years. The Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Examination was used to monitor course of illness and to identify any hypomania or mania. The association of subthreshold hypomanic symptoms at baseline with subsequent hypomania or mania was determined in survival analyses using Cox proportional hazards regression.

Results:

With a cumulative probability of one in four on survival analysis, 19.6% (N=108) of the sample experienced hypomania or mania, resulting in revision of diagnoses for 12.2% to bipolar II disorder and 7.5% to bipolar I disorder. Number of subthreshold hypomanic symptoms, presence of psychosis, and age at illness onset predicted progression to bipolar disorder. Decreased need for sleep, unusually high energy, and increased goal-directed activity were specifically implicated.

Conclusions:

Symptoms of hypomania, even when of low intensity, were frequently associated with subsequent progression to bipolar disorder, although the majority of patients who converted did not have any symptoms of hypomania at baseline. These results suggest that continued monitoring for the possibility of progression to bipolar disorder is necessary over the long-term course of major depressive disorder.

Bipolar disorder is characterized by recurrent episodes of hypomania or mania and major depression. Because bipolar disorder may present with depression, patients who present with major depression may have either major depressive disorder or a bipolar disorder that would not be recognized until the occurrence of a defining mania or hypomania. Subthreshold hypomanic symptoms have been posited to be of nosological relevance (1–3), although the predictive validity of such symptoms toward the development of a frank bipolar disorder has not been established.

Prospective cohort studies with structured diagnostic interviews of individuals with major depression at baseline have reported varied rates of diagnostic conversion to bipolar disorder (4–12), as detailed in Table 1. The rate reported by a representative community sample of adolescents and young adults in Germany (4) appears to be lower than that from clinical samples. Higher rates of conversion are seen in the child and adolescent samples (7–12). In a sample of seriously ill inpatients in Switzerland, the rate of conversion was greatest in the first 4 years after onset of the first episode and thereafter was linear, with a change rate of about 1.25% per year (13). An analysis of the National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Depression Study (CDS) at 10 years of follow-up showed that approximately 10% of those with major depression developed bipolar disorder (5). The present study extends these findings after up to 31 years of follow-up.

| Authors, Year (Reference) | N | Age at Intake (Years) | Sample Acuity | Duration of Follow-Up (Years) | Number of Prospective Assessments | Bipolar II Disorder (%) | Bipolar I Disorder (%) | Total Conversion (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean or Range | SDb | Actual or Mean | SDb | |||||||

| Beesdo et al., 2009 (4) | 649 | 14–24c | Representative community sample | ∼7c | 3 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 4.0 | ||

| Coryell et al., 1995 (5) | 381 | 36.8 | 13.6 | ¾ inpatient | 10 | 15 | 5.0 | 5.2 | 10.2 | |

| Goldberg et al., 2001 (6) | 74 | 23.0 | 3.8 | Inpatient | 14.7 | 5 | 25.7 | 14.9 | 40.5 | |

| Kovacs et al., 1994 (7) | 60 | 11.1 | Outpatient | 6.3 | Not reported | 15.0 | ||||

| McCauley et al., 1993 (8) | 65 | 12.3 | 2.6 | Inpatient and outpatient | 3 | 4 | 6.2 | 1.5 | 7.7 | |

| Rao et al., 1995 (9) | 26 | 15.4 | 1.3 | <½ inpatient | 7.0 | 0.5 | 1 | 19.2 | ||

| Strober and Carlson, 1982 (10) | 60 | ∼15 | Inpatient | 3–4 | 6–8 | 0.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 | ||

| Strober et al., 1993 (11) | 58 | ∼15 | Inpatient | 2 | 4 | 8.6 | ||||

| Geller et al., 2001 (12) | 72 | 10.3d | 1.5 | Outpatient | 9.9 | 1.5 | Not reported | 15.3 | 33.3 | 48.6 |

TABLE 1. Studies of Diagnostic Conversion from Unipolar Major Depression to Bipolar Disordera

Several variables have been prospectively associated with the development of mania or hypomania in major depression. The most robust predictors, based on replication in several studies of separate samples, include early age at illness onset (4, 13, 14), presence of psychosis (5, 6, 10, 11, 14), and a family history of mania (5, 10, 12–14). The presence of a pedigree loaded with affective illness has also been associated with development of bipolar disorder (14), especially in child and adolescent samples (10, 12, 15). The higher conversion rates reported from child and adolescent samples (7–12) may be explained in part by the high rates of familial aggregation seen in child probands with bipolar disorder (16, 17) or a possible secular trend for early age at onset in more recently born cohorts (18). Other clinical predictors of progression to bipolar disorder reported by more than one study include acute onset of mood syndrome (10, 19), multiple prior depressive episodes (4, 13), and hypersomnia or psychomotor retardation (10, 14). There is a surprising paucity of research on whether subthreshold hypomanic symptoms may predict progression to bipolar disorder, although one recent study supports this hypothesis (20).

We sought to determine the diagnostic conversion rate from major depression to bipolar disorder. We also assessed whether subthreshold hypomanic symptoms predicted subsequent diagnostic conversion, alone and in relation to established risk factors. The CDS data are ideally suited to making accurate estimates of conversion among patients with major depression at study intake because of its long and relatively high-intensity follow-up. All participants were screened for a history of manic symptoms in five domains during the intake episode: elevated mood, decreased need for sleep, unusually high energy, increased goal-directed activity, and grandiosity. To our knowledge, this is the first analysis to systematically assess the impact of subthreshold manic symptoms on subsequent diagnostic conversion to bipolar disorder.

Method

Participants

Patients with mood disorders were recruited for the CDS from five academic centers: Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard University (Boston), Rush Presbyterian–St. Luke's Medical Center (Chicago), the University of Iowa (Iowa City), New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University (New York City), and Washington University School of Medicine (St. Louis). The study was approved by the institutional review boards of all sites. All participants were Caucasian (genetic hypotheses were examined), spoke English, had knowledge of their biological parents, and provided written consent. Treatment was not assigned or required in this observational study. Participants met Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) for major depressive disorder, schizoaffective disorder, or manic disorder at study intake based on medical records and use of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS) (21, 22).

Intake diagnosis was used to identify participants with major depression, based on an intake RDC diagnosis of major depressive disorder or schizoaffective disorder, depressed, mainly affective. DSM-IV-TR criteria for major depressive disorder are very similar to RDC criteria for these conditions. Age at onset and co-occurring conditions were identified at study intake. Restricting the sample to patients with at least 1 year of follow-up to ensure a minimum of two follow-up assessments yielded 550 participants who had major depression.

Procedures

The SADS was used to identify the presence of delusions, hallucinations, hypersomnia, and psychomotor retardation. To determine family history, we analyzed data on consensus diagnoses for 2,467 first-degree biological relatives who were interviewed in person or by telephone as part of a family study in which 331 individuals from this sample participated. Raters blind to proband diagnosis used the lifetime version of the SADS to interview all adult first-degree relatives willing to participate. Investigators formulated a consensus diagnosis from the SADS and all available sources of information to derive RDC diagnoses. Consensus diagnoses for 1,519 first-degree relatives of another 214 CDS participants who did not participate in the family study were based on the Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria, which uses an interview with one or more family members to estimate diagnoses on relatives not interviewed. Diagnoses from family history data were unavailable for only five participants (0.9%), for whom these data were imputed as negative. The CDS sample and the family study have been described elsewhere (23–25).

The SADS screened all participants at baseline for five manic symptoms. Raters were well-trained on the instrument (26) and demonstrated reliability for these manic symptoms; intraclass correlation coefficients were 0.98 for elevated mood, 0.96 for decreased need for sleep, 0.93 for unusually high energy, 0.86 for increased goal-directed activity, and 0.73 for grandiosity (27). Participants were not uniformly screened for other symptoms of mania. Each item was rated on a 6-point scale. The sleep item focused on the amount of sleep needed to “feel rested” compared to usual need. The scale for the relevant SADS items is available in the data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article. Any score greater than 1 was used to signify the presence of the symptom, both because of the study's focus on subthreshold symptoms and because of the low frequencies for higher scores in this sample. The low threshold allowed the identification of symptoms that would not warrant a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. The total number of items present with a score greater than 1 (range=0–5) was tested as a predictor for subsequent development of manic symptoms. In a secondary analysis, the sum of the scores on these five items (range=5–30) was calculated.

Follow-up assessments were completed using the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation (28) or a revised version of it, which was administered every 6 months during the first 5 years and annually thereafter, tracking the severity of each RDC syndrome weekly to identify the week of onset for any hypomania or mania that developed during follow-up.

Data Analysis

Participants who converted to bipolar I or II disorder were compared with those who did not, using analysis of variance for continuous measures and chi-square tests for categorical measures. Survival was examined using the Kaplan-Meier product limit estimator, with survival time reflecting the primary outcome of time to onset of hypomania or mania. An additional analysis modeled time to hypomania (progression to bipolar II) in those who did not later develop mania and time to mania (progression to bipolar I). Participants were censored on loss to follow-up, death, dropout, or end of the study. Survival analysis was also performed using Cox proportional hazards regression. Primary analyses were unadjusted. Later analyses included covariates for the most robust predictors from previous studies: age at illness onset, presence of psychosis (hallucinations or delusions), and family history of bipolar disorder. Also included in models were any sociodemographic variables found to be associated with both affirmative responses to manic screening questions and outcome. Age at intake and age at onset were each modeled as continuous, assuming a linear effect. Censoring and diagnostic conversion were assumed to be independent. Proportional hazards were assumed for all variables modeled in Cox regression. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.), with the exception of receiver operating characteristic analysis (29). Kaplan-Meier survival curves were calculated using SPSS, version 17.0 (SPSS, Chicago).

Results

Of the 550 participants with at least 1 year of follow-up, the mean duration of follow-up was 17.5 years (median=19.9, SD=9.9, maximum=31); 390 (70.9%) participants completed at least 10 years of follow-up. A diagnostic conversion to bipolar disorder was made in 108 (19.6%) participants. A majority of these conversions (N=67; 12.2% of the overall sample) involved the development of hypomania without mania. Of the 41 (7.5% of the overall sample) who developed mania, 24 (59%) had a preceding hypomania. Table 2 outlines the demographic characteristics for this subsample of the CDS. At intake, the participants who experienced a prospectively observed mania or hypomania were significantly younger, were less likely to be married, had an earlier age at illness onset, and were more likely to have delusions. Those who eventually developed mania or hypomania were more likely to have had a family history of bipolar disorder, and the family history was generally consistent with the specific bipolar subtype of their ultimate diagnosis. Of those rediagnosed as having bipolar I, 10% had a family history of bipolar I, compared with 1% of those with bipolar II. Of those rediagnosed as having bipolar II disorder, 19% had a family history of bipolar II, compared with 15% of those with bipolar I. There were no differences with regard to gender or inpatient status at intake.

| Characteristic | Prospective Diagnosis | Entire Sample (N=550) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major Depressive Disorder (N=442) | Bipolar I Disorder (N=41) | Bipolar II Disorder (N=67) | ||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Age at study intakea (years) | 39 | 15 | 36 | 13 | 33 | 13 | 38 | 14 |

| Age at illness onseta (years) | 31 | 14 | 27 | 13 | 24 | 9 | 30 | 14 |

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Female | 267 | 60 | 27 | 66 | 47 | 70 | 341 | 62 |

| Inpatient | 335 | 76 | 34 | 83 | 51 | 76 | 420 | 76 |

| Delusionsa | 39 | 9 | 13 | 32 | 9 | 13 | 61 | 11 |

| Hallucinations | 27 | 6 | 6 | 15 | 6 | 9 | 39 | 2 |

| Number of previous episodes | ||||||||

| 0 | 157 | 36 | 12 | 29 | 17 | 25 | 186 | 34 |

| 1 | 115 | 26 | 6 | 15 | 17 | 25 | 138 | 25 |

| 2 | 63 | 14 | 5 | 12 | 10 | 15 | 78 | 14 |

| 3 | 37 | 8 | 8 | 20 | 7 | 10 | 52 | 9 |

| ≥4 | 70 | 16 | 10 | 24 | 16 | 23 | 96 | 17 |

| Family history of major depression | 224 | 51 | 17 | 41 | 36 | 54 | 277 | 51 |

| Family history of bipolar disordera | 40 | 9 | 8 | 20 | 13 | 19 | 61 | 11 |

| Family history of bipolar I disorderb | 11 | 2 | 4 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 16 | 3 |

| Family history of bipolar II disordera | 30 | 7 | 6 | 15 | 13 | 19 | 49 | 9 |

| Psychomotor retardation | 180 | 33 | 18 | 44 | 31 | 46 | 229 | 42 |

| Hypersomnia | 151 | 34 | 18 | 44 | 27 | 40 | 196 | 36 |

| Marital statusb | ||||||||

| Married | 216 | 49 | 14 | 34 | 20 | 30 | 250 | 45 |

| Divorced or separated | 72 | 16 | 9 | 22 | 16 | 24 | 97 | 18 |

| Single | 133 | 30 | 15 | 37 | 30 | 45 | 178 | 32 |

| Widowed | 21 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 25 | 5 |

| Education level | ||||||||

| Without diploma | 86 | 19 | 0 | 11 | 16 | 97 | 18 | |

| High school graduate | 119 | 27 | 13 | 32 | 17 | 25 | 149 | 27 |

| Some college | 130 | 29 | 15 | 37 | 19 | 28 | 164 | 30 |

| College graduate | 107 | 24 | 13 | 32 | 20 | 30 | 140 | 25 |

| Co-occurring psychiatric diagnoses | ||||||||

| Alcohol abuse | 113 | 26 | 13 | 32 | 19 | 28 | 145 | 26 |

| Drug abuse | 26 | 6 | 4 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 37 | 7 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 30 | 7 | 5 | 12 | 4 | 6 | 39 | 7 |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 7 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 9 | 2 | |

| Panic disorder | 18 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 9 | 24 | 4 | |

| Phobic disorder | 33 | 7 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 6 | 40 | 7 |

TABLE 2. Baseline Characteristics of Patients With a Diagnosis of Major Depression at Study Entry, by Subsequent Diagnosis

The majority of participants (N=431, 78%) did not endorse any manic symptoms on screening; 52 individuals (9.5%) endorsed one symptom, 26 (4.7%) endorsed two symptoms, 14 (2.5%) endorsed three symptoms, 18 (3.3%) endorsed four symptoms, and 9 (1.6%) endorsed all five symptoms. Subthreshold manic symptoms reported included elevated or expansive mood (N=60, 11%), decreased need for sleep (N=36, 7%), unusually high energy (N=64, 12%), increase in goal-directed activity (N=65, 12%), and grandiosity (N=38, 7%). Gender and marital status were not associated with total number of manic symptoms screened positive. Total number of manic symptoms screened positive was negatively correlated with age at intake (Kruskal-Wallis χ2=23.4, df=5, p=0.0003) and was not related to subsequent antidepressant treatment.

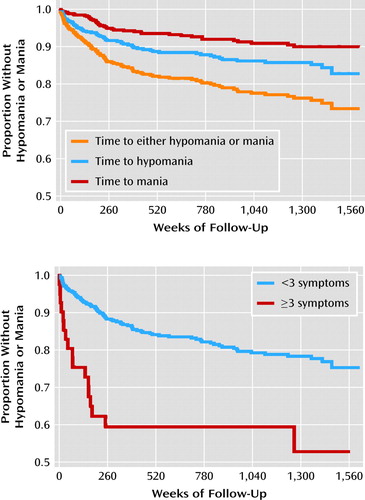

Kaplan-Meier survival curves (Figure 1) illustrate the time to development of any hypomanic or manic syndrome, of mania, and of hypomania without subsequent mania. In the primary Cox regression analyses, the total number of manic symptoms present at intake predicted the onset of hypomania or mania, with each additional symptom conferring an increased risk of 29% (hazard ratio=1.29, 95% CI=1.13–1.47, p=0.0001). This measure was also associated with time to mania (hazard ratio=1.41, 95% CI=1.17–1.69, p=0.0003), although it was not significantly associated with time to hypomania (hazard ratio=1.14, 95% CI=0.94–1.37, p=0.17). As illustrated in the figure, the cumulative probability of developing mania or hypomania was approximately one in four (26.3%).

FIGURE 1. Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves for Time to Change in Diagnosis for Patients With Major Depressive Disorder (N=550)a

a As shown in the upper panel, in the first 5 years, the rate of change in diagnosis approximates 2.5% per year and thereafter declines in a near linear fashion at a rate of roughly 0.5% per year. The survival curve in the lower panel contrasts the change in diagnosis of those with (N=41) and those without (N=509) three or more subthreshold hypomanic symptoms at intake.

The total score for manic screening questions (the sum of the scores on the five items) further predicted development of hypomania or mania (hazard ratio=1.34, 95% CI=1.17–1.54, p<0.0001), suggesting a 34% increase in risk of developing hypomania or mania for every increase of one standard deviation (2.5 points) on this metric. These results proved similarly significant for hypomania (hazard ratio=1.23, 95% CI=1.02–1.17, p=0.03) and mania (hazard ratio=1.28, 95% CI=1.09–1.52, p=0.003).

Multivariate models determined the magnitude of these associations compared with the most robust predictors in the literature. With age at intake, age at illness onset, presence of psychosis, and family history of bipolar disorder as covariates, the total number of manic symptoms was similarly associated with subsequent mania or hypomania (hazard ratio=1.24, 95% CI=1.09–1.41, p=0.001). Table 3 details the hazard ratio estimates for these multivariate models. Psychosis at study intake was associated with the development of mania, and earlier age at illness onset was associated with the subsequent development of hypomania without mania. Having a family history of bipolar disorder was associated with time to mania or hypomania. In a post hoc analysis, having a family history of bipolar I appeared to be related to time to mania (hazard ratio=3.85, 95% CI=1.23–12.00, p=0.02), and having a family history of bipolar II was associated with time to hypomania without subsequent mania (hazard ratio=2.07, 95% CI=1.12–3.82, p=0.02).

| Variable | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Time to either hypomania or mania | |||

| Number of positive manic screens | 1.24 | 1.09–1.41 | 0.001 |

| Age at onset | 0.97 | 0.95–1.00 | 0.02 |

| Family history of bipolar disorder | 1.91 | 1.18–3.08 | 0.008 |

| Psychosis | 1.97 | 1.25–3.10 | 0.004 |

| Age at intake | 1.00 | 0.98–1.03 | 0.67 |

| Model 2: Time to mania | |||

| Number of positive manic screens | 1.40 | 1.16–1.68 | 0.0004 |

| Age at onset | 0.98 | 0.95–1.02 | 0.34 |

| Family history of bipolar disordera | 1.93 | 0.88–4.21 | 0.10 |

| Psychosis | 3.54 | 1.85–6.77 | 0.0001 |

| Age at intake | 1.01 | 0.98–1.05 | 0.41 |

| Model 3: Time to hypomania with no mania ever | |||

| Number of positive manic screens | 1.07 | 0.89–1.29 | 0.48 |

| Age at onset | 0.97 | 0.94–1.00 | 0.03 |

| Family history of bipolar disordera | 1.71 | 0.93–3.15 | 0.08 |

| Psychosis | 1.11 | 0.56–2.17 | 0.77 |

| Age at intake | 1.00 | 0.97–1.03 | 0.95 |

TABLE 3. Cox Proportional Hazards Ratio Estimates, With Covariates, for the Association of Number of Positive Mania Screen Items With Onset of Mania or Hypomania in Major Depression

Secondary analyses sought to determine which items from the SADS appeared to be most relevant to the prediction of mania or hypomania. Because the individual items were highly correlated, they were entered separately into models. In univariate analyses, three manic symptoms individually predicted hypomania or mania: decreased need for sleep, unusually high energy, and increased goal-directed activity. Decreased need for sleep, unusually high energy, increased goal-directed activity, and grandiosity were predictive specifically of mania. Decreased need for sleep and unusually high energy predicted hypomania without mania. These results are highlighted in Table 4.

| Variable | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time to either hypomania or mania | |||

| Elevated or expansive mood | 1.35 | 0.78–2.33 | 0.28 |

| Decreased need for sleep | 3.07 | 1.78–5.31 | <0.0001 |

| Unusually energetic | 2.71 | 1.72–4.26 | <0.0001 |

| Increase in goal-directed activity | 2.29 | 1.43–3.66 | 0.0005 |

| Grandiosity | 1.73 | 0.92–3.22 | 0.09 |

| Time to mania | |||

| Elevated or expansive mood | 1.64 | 0.73–3.71 | 0.23 |

| Decreased need for sleep | 3.37 | 1.49–7.61 | 0.003 |

| Unusually energetic | 3.49 | 1.78–6.83 | 0.003 |

| Increase in goal-directed activity | 2.91 | 1.46–5.80 | 0.003 |

| Grandiosity | 3.68 | 1.70–7.97 | 0.001 |

| Time to hypomania with no mania ever | |||

| Elevated or expansive mood | 1.11 | 0.53–2.32 | 0.79 |

| Decreased need for sleep | 2.30 | 1.10–4.81 | 0.03 |

| Unusually energetic | 1.87 | 1.001–3.49 | 0.05 |

| Increase in goal-directed activity | 1.60 | 0.84–3.06 | 0.15 |

| Grandiosity | 0.63 | 0.20–2.02 | 0.44 |

TABLE 4. Cox Proportional Hazards Ratio Estimates for the Association of Individual Manic Symptoms With Onset of Mania or Hypomania in Major Depression (Univariate Analysis)

To estimate the clinical utility of the above findings, receiver operating characteristic curves were performed on the total number of manic symptoms present at intake. A fitted receiver operating characteristic curve yielded an area of 0.61. An optimal cutoff of ≥3 manic symptoms was identified, which yielded a sensitivity of 16% and specificity of 95%. The positive predictive value for this cutoff was 42%, and the negative predictive value was 82%. With 73/431 (16.9%) of individuals without any subclinical hypomanic symptoms at baseline subsequently developing hypomania or mania, lowering the threshold only improved sensitivity to a maximum of 32%.

Discussion

At the close of this prospective cohort study, approximately one-fifth of patients who had a diagnosis of major depressive disorder at study entry progressed to bipolar disorder, with a cumulative probability of one-quarter in survival analysis. The number of subthreshold hypomanic symptoms present was associated with the subsequent onset of threshold mania or hypomania, independent of established risk factors. Among the individual symptoms, elevated or expansive mood was not associated with later progression to bipolar disorder, which is noteworthy given its nosological position as a stem criterion for hypomania or mania. Many individuals who did not endorse a history of subthreshold hypomanic symptoms went on to develop hypomania or mania. The presence of the symptoms was therefore not very sensitive for the detection of subsequent mania. However, when present in sufficient quantities (with three of five as the optimal cutoff), these symptoms proved to be quite specific, although the positive predictive value was only 41.5%.

Akin to previously reported data showing higher rates of diagnostic conversion or progression early in follow-up, our analysis shows more rapid progression in the first 5 years of follow-up, followed by a slower, linear decline thereafter. The slower decline corresponded to the time when surveillance decreased from semiannually to annually. Angst et al. (13) reported a similar pattern when intensity of surveillance decreased from approximately every 2 years to every 5 years. The lower frequency of surveillance in the Angst et al. study nonetheless did not yield lower rates of progression. It is difficult to discern whether this change in progression rates at year 5 reflects a greater likelihood of progression earlier in the course of illness or an artifact of surveillance bias. Presumably, any such surveillance bias would disproportionately influence milder, more subtle episodes of mood elevation symptoms, yet our finding is evident for the development of both mania and hypomania without mania. This finding was present only in the younger half of the sample, which further reduces the likelihood that it represents an artifact of surveillance bias. The overall rate of progression observed was lower than in other prospective studies. A variety of variables may influence this rate, including the sample's mean age and acuity of illness, the accuracy of intake diagnosis, and the rigor of prospective monitoring. Our sample was older at intake than others. If progressing to bipolar disorder is more likely to happen at younger ages, our sample may have had fewer at risk of converting.

The family history of participants with major depression who developed mania or hypomania was more likely to include first-degree relatives with bipolar disorder. Those with a family history of bipolar I were more likely to develop mania, and those with a family history of bipolar II were more likely to develop hypomania without mania. These findings strengthen previous analyses from the CDS showing a high proportion of bipolar II individuals in the families of bipolar II probands (30). In this case, our findings extend to some who were initially “misclassified” as having a unipolar major depression before the onset of the defining features of bipolar disorder. This lends further support to the validity of bipolar II and highlights just some of the challenges inherent to genetic studies of mood disorders.

Our study generally replicated the most robust predictors identified from previous studies. However, contrary to the findings of Angst et al. (13), our analysis found that an early age at onset was associated with a change in diagnosis to bipolar II but not bipolar I. Akiskal et al. (19) previously identified an association of energy and activity with conversion to bipolar II and psychotic symptoms with conversion to bipolar I with CDS data at up to 11 years of follow-up, and our findings extend the follow-up period to 31 years. Another CDS analysis (31) found delusions in the setting of major depression and a family history of bipolar disorder to be associated with bipolar as opposed to unipolar depression. Our analysis similarly found that these features, when present in major depression, were associated with subsequent progression to bipolar disorder. Our results uniquely contribute to the literature in associating subthreshold hypomanic symptoms with progression from major depression to bipolar disorder in a prospective sample followed for several decades.

There are several limitations of this observational study. Our relatively high-acuity sample may not generalize to lower-acuity populations. Subthreshold hypomanic symptoms were assessed at study intake, posing some risk for misclassification of exposure over the course of follow-up. Limitations in rating assessments and the potential for lack of insight into manic symptoms may have also contributed to misclassification. These assessments were, however, systematically collected on all participants at intake for the current episode prior to the time of evaluation. Treatment was not controlled for in this cohort, and patients received a variety of treatments (or no treatment) during follow-up. Those with a history of subthreshold hypomanic symptoms were not differentially treated with antidepressants. Treatments could have influenced the development of mania or hypomania, although the accumulated evidence does not generally support the assumption that antidepressants induce mania (32–37). In prospective studies, all who developed antidepressant-associated mania went on to later have episodes of spontaneous mania, although these studies included a limited number of cases with pharmacologically induced hypomania (10, 14). The family histories of those with antidepressant-associated mania further resemble those of individuals with spontaneous mania. For these reasons, opinion leaders do not currently distinguish antidepressant-induced mania from mania that arises spontaneously (38), and this assumption underlies our analyses (39, 40). The proposed revisions for DSM-V now also include the caveat that “a full manic [or hypomanic] episode emerging during antidepressant treatment (medication, ECT, etc.) and persisting beyond the physiological effect of that treatment is sufficient evidence for a manic [or hypomanic] episode diagnosis.”

Our participants were interviewed semiannually for the first 5 years of follow-up and annually thereafter. Although the interval histories were reconstructed in a systematic and reliable manner, the potential for recall bias exists. Some hypomanic episodes could have been missed, and our estimate of diagnostic conversion may therefore be underestimated. Although differential surveillance for the first 5 years compared with subsequent years could influence reported rates of progression, there was certainly no differential surveillance by exposure (presence of subthreshold hypomanic symptoms) to influence the associations observed. As mentioned earlier, such bias would be expected to affect hypomania more than mania, and a change in rates of diagnostic conversion after 5 years was observed for both hypomania and mania. Furthermore, it is biologically plausible that individuals with bipolar disorder would be likely to first manifest the defining features of illness (hypomania and mania) earlier in the course of illness, particularly given a mean age at illness onset of 18.2 years (SD=11.6) for bipolar I disorder and 20.3 years (SD=9.7) for bipolar II disorder (1).

Notable strengths of this study include the rigor of phenomenological assessments and the long duration of relatively intense follow-up, which increased our ability to capture eventual mood elevation syndromes. Furthermore, the baseline assessments included a comprehensive structured interview and medical record review, decreasing the risk of false negatives at intake (i.e., misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder as major depression), which could inflate estimates of subsequent diagnostic conversion.

Our data demonstrate that a substantial portion of individuals treated clinically for major depression will ultimately be recognized as having a bipolar disorder. Our findings further suggest that the presence of even low-grade hypomanic symptoms may be as strongly associated with progression to bipolar disorder as the most robustly established predictors to date. Although survival analyses are most appropriate for these time-to-event data, the secondary receiver operating characteristic analyses demonstrated a modest area under the curve and positive predictive value, such that these subclinical hypomanic symptoms would certainly not warrant a change in diagnosis. This suggests that our ability to recognize those individuals with major depression who will go on to develop hypomania or mania remains limited and underscores the importance of rigorously evaluating and closely monitoring patients in treatment for mood disorders.

1. : Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007; 64:543–552Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. : Toward a re-definition of subthreshold bipolarity: epidemiology and proposed criteria for bipolar-II, minor bipolar disorders, and hypomania. J Affect Disord 2003; 73:133–146Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. : Manic symptoms during depressive episodes in 1,380 patients with bipolar disorder: findings from the STEP-BD. Am J Psychiatry 2009; 166:173–181Link, Google Scholar

4. : Mood episodes and mood disorders: patterns of incidence and conversion in the first three decades of life. Bipolar Disord 2009; 11:637–649Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. : Long-term stability of polarity distinctions in the affective disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:385–390Link, Google Scholar

6. : Risk for bipolar illness in patients initially hospitalized for unipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1265–1270Link, Google Scholar

7. : Childhood-onset dysthymic disorder: clinical features and prospective naturalistic outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:365–374Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. : Depression in young people: initial presentation and clinical course. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1993; 32:714–722Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. : Unipolar depression in adolescents: clinical outcome in adulthood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:566–578Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. : Bipolar illness in adolescents with major depression: clinical, genetic, and psychopharmacologic predictors in a three- to four-year prospective follow-up investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982; 39:549–555Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. : The course of major depressive disorder in adolescents, I: recovery and risk of manic switching in a follow-up of psychotic and nonpsychotic subtypes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1993; 32:34–42Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. : Bipolar disorder at prospective follow-up of adults who had prepubertal major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:125–127Link, Google Scholar

13. : Diagnostic conversion from depression to bipolar disorders: results of a long-term prospective study of hospital admissions. J Affect Disord 2005; 84:149–157Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. : Bipolar outcome in the course of depressive illness: phenomenologic, familial, and pharmacologic predictors. J Affect Disord 1983; 5:115–128Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. : Rate and predictors of prepubertal bipolarity during follow-up of 6- to 12-year-old depressed children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1994; 33:461–468Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. : A family study of bipolar I disorder in adolescence: early onset of symptoms linked to increased familial loading and lithium resistance. J Affect Disord 1988; 15:255–268Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. : Controlled, blindly rated, direct-interview family study of a prepubertal and early-adolescent bipolar I disorder phenotype: morbid risk, age at onset, and comorbidity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63:1130–1138Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. : Studies of anticipation in bipolar affective disorder. CNS Spectr 2002; 7:196–202Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. : Switching from “unipolar” to bipolar II: an 11-year prospective study of clinical and temperamental predictors in 559 patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:114–123Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. : Heterogeneity of DSM-IV major depressive disorder as a consequence of subthreshold bipolarity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009; 66:1341–1352Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. : A diagnostic interview: the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35:837–844Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. : Use of the Research Diagnostic Criteria and the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia to study affective disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1979; 136:52–56Link, Google Scholar

23. : Reliability of lifetime diagnosis: a multicenter collaborative perspective. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 38:400–405Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. : Introduction: overview of the clinical studies program. Am J Psychiatry 1979; 136:49–51Link, Google Scholar

25. : Familial rates of affective disorder: a report from the National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:461–469Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. : Mastering the art of research interviewing: a model training procedure for diagnostic evaluation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 38:1259–1262Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. : Assessment of reliability in multicenter collaborative research with a videotape approach. Am J Psychiatry 1982; 139:876–882Link, Google Scholar

28. : The Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation: a comprehensive method for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:540–548Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. : ROC analysis: web-based calculator for ROC curves. http://wwwjrocfitorgGoogle Scholar

30. : A family study of bipolar II disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1984; 145:49–531Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. : Distinguishing bipolar major depression from unipolar major depression with the Screening Assessment of Depression–Polarity (SAD-P). J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67:434–442Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. : Switch from depression to mania: a record study over decades between 1920 and 1982. Psychopathology 1985; 18:140–154Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. : Switch from depression to mania, or from mania to depression: role of psychotropic drugs. Psychopharmacol Bull 1987; 23:66–67Medline, Google Scholar

34. : The long-term course of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:914–920Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. : Antidepressants for bipolar depression: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:1537–1547Link, Google Scholar

36. : The induction of mania: a natural history study with controls. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982; 39:303–306Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. : Effectiveness of adjunctive antidepressant treatment for bipolar depression. N Engl J Med 2007; 356:1711–1722Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. : A review of antidepressant-induced hypomania in major depression: suggestions for DSM-V. Bipolar Disord 2004; 6:32–42Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. : Validating antidepressant-associated hypomania (bipolar III): a systematic comparison with spontaneous hypomania (bipolar II). J Affect Disord 2003; 73:65–74Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. : Manic/hypomanic switch during acute antidepressant treatment for unipolar depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2006; 26:512–515Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar